Chachapoya culture

The Chachapoyas, also called the "Warriors of the Clouds", was a culture of Andes living in the cloud forests of the Amazonas Region of present-day Peru. The Inca Empire conquered their civilization shortly before the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. At the time of the arrival of the conquistadors, the Chachapoyas were one of the many nations ruled by the Incas, although their incorporation had been difficult due to their constant resistance to Inca troops.

Since the Incas and conquistadors were the principal sources of information on the Chachapoyas, there is little first-hand or contrasting knowledge of the Chachapoyas. Writings by the major chroniclers of the time, such as Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, were based on fragmentary second-hand accounts. Much of what we do know about the Chachapoyas culture is based on archaeological evidence from ruins, pottery, tombs and other artifacts. Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de León noted that, after their annexation to the Inca Empire, they adopted customs imposed by the Cusco-based Inca. By the 18th century, the Chachapoyas had been devastated; however, they remain a distinct strain within the indigenous peoples of modern Peru.

Etymology

The name Chachapoya was given to this culture by the Inca; the name that these people may have actually used to refer to themselves is not known. The meaning of the word Chachapoyas may be derived from the Quechua sach'a phuyu (sach'a = tree,[1] phuyu = cloud[2]) meaning "cloud forest", another alternative is that it may have been from sach'a-p-qulla (sach'a = tree, p = of the, qulla = the name of a pre-Inca kingdom from Puno that the Incas used as a collective term for the many kingdoms around the Titicaca) the equivalent of "qulla people who live in the woods".

Geography

The Chachapoyas' territory was located in the northern regions of the Andes in present-day Peru. It encompassed the triangular region formed by the confluence of the Marañón River and the Utcubamba in Bagua Province, up to the basin of the Abiseo River where the Gran Pajáten is located. This territory also included land to the south up to the Chuntayaku River, exceeding the limits of the current Amazonas Region towards the south. But the center of the Chachapoyas culture was the basin of the Utcubamba river. Due to the great size of the Marañón river and the surrounding mountainous terrain, the region was relatively isolated from the coast and other areas of Peru, although there is archaeological evidence of some interaction between the Chachapoyas and other cultures.

The contemporary Peruvian city of Chachapoyas, Peru derives its name from the word for this ancient culture as does the defined architectural style. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega noted that the Chachapoyas territory was so extensive that

We could easily call it a kingdom because it has more than fifty leagues long per twenty leagues wide, without counting the way up to Muyupampa, thirty leagues long more (...)

A league was a measurement of about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi).

The area of the Chachapoyas is sometimes referred to as the "Amazonian Andes" due to it being part of a mountain range covered by dense tropical forest. The Amazonian Andes constitute the eastern flank of the Andes, which were once covered by dense Amazon vegetation. The region extended from the cordillera spurs up to altitudes where primary forests still stand, usually above 3,500 metres (11,500 ft). The cultural realm of the Amazonian Andes occupied land situated between 2,000–3,000 metres (6,600–9,800 ft).

Archaeological sites

Excavations at Manachaqui Cave, in Pataz District, recovered evidence of very early human occupation,

Two AMS dates calibrated to approximately 12,200 and 11,900 BP (dates calibrated using McCormac et al. 2004; OxCal v.3.10, Bronk Ramsey 2005 unless otherwise noted) accompany scrapers, gravers, burins, and stemmed projectile points (see Figure 45.2a-g) resembling north coastal Peruvian Paiján (Chauchat 1988) and highland Ecuadorian El Inga styles (Bell 2000).[3]

The finds at Manachaqui’s late Pre-ceramic Period levels also yield radiocarbon dates averaging 2700 BC.[3]

Around 1400 BC, the Initial Period Manachaqui phase witnessed the adoption of ceramic technology and the appearance of a “Chachapoya ceramic tradition”. Ceramics found at the central Chachapoyas site of Huepón were given a later date.[3]

Despite the archaeological evidence that people began settling as early as 200 CE or before, the Chachapoyas culture is thought to have developed around 750-800.

The major urban centers, such as the great fortress of Kuelap, with more than four hundred interior buildings and massive exterior stone walls reaching upwards of 60 feet (18 m) in height, and Gran Pajatén possibly served to defend against the Wari culture around 800, a Middle Horizon culture that covered much of the coast and highlands. Referred to as the 'Machu Picchu of the north,' Kuélap receives few visitors due to its remote location.

Other archaeological sites in the region include the settlement of Gran Saposoa, the Atumpucro complex, and the burial sites at Revash and Laguna de las Momias ("Mummy Lake"), among others. It is estimated that only 5% of sites of the Chachapoyas have been excavated according to a BBC documentary from January 2013.

Inca occupation and forced resettlement

The conquest of the Chachapoyas by the Inca Empire took place, according to Garcilaso, during the government of Tupac Inca Yupanqui in the second half of the 15th century. He recounts that the warlike actions began in Pias, a community on a mountain on the edge of Chachapoyas territory likely to the southwest of Gran Pajatén.

According to de la Vega, the Chachapoyas anticipated an Inca incursion and began preparations to withstand it at least two years earlier. The chronicle of Pedro Cieza de León also documents Chachapoya resistance. During the time of Huayna Capac's regime, the Chachapoyas rebelled:

They had killed the Inca's governors and captains (...) and (...) soldiers (...) and many others were imprisoned, they had the intention to make them their slaves.

In response, Huayna Capac, who was in the Ecuadorian cañaris land at the time, sent messengers to negotiate peace. But again, the Chachapoyas "punished the messengers (...) and threatened them with death". Huayna Capac then ordered an attack. He crossed the Marañón over a bridge of wooden rafts that he ordered to be built probably near Balsas District near Celendín.

From here, Inca troops proceeded to Cajamarquilla (now in Bolívar Province, Peru), with the intention of destroying "one of the principal towns" of the Chachapoyas. From Cajamarquilla, a delegation of women came to meet them, led by a matron who was a former concubine of Tupac Inca Yupanqui, Huayna Capac's father. They asked for mercy and forgiveness, which the Sapa Inca granted them. In memory of this event of a peace agreement, the place where the negotiation had taken place was declared sacred and closed so from now on "neither men nor animals, nor even birds, if it were possible, would put their feet in it."

To assure the pacification of the Chachapoyas, the Incas installed garrisons in the region. They also arranged the transfer of groups of villagers under the system of mitma (forced resettlement):

It gave them grounds to work and places for houses not much far from a hill that is next to the city (Cusco) called Carmenga.

The Inca presence in the territory of Chachapoyas left structures at Quchapampa, Amazonas in the outskirts of the Utcubamba in the current Leimebamba District, as well as other sites.

In the fifteenth century, the Inca empire expanded to incorporate the Chachapoyas region. Although fortifications such as the citadel at Kuélap may have been an adequate defense against the invading Inca, it is possible that by this time the Chachapoyas settlements had become decentralized and fragmented after the threat of Wari invasion had dissipated. The Chachapoyas were conquered by Inca ruler Tupac Inca Yupanqui around 1475. The defeat of the Chachapoyas was fairly swift; however, smaller rebellions continued for many years. Using the mitma system of ethnic dispersion, the Inca attempted to quell these rebellions by forcing large numbers of Chachapoya people to resettle in remote locations of the empire.

When civil war broke out within the Inca Empire, the Chachapoyas were located on middle ground between the northern capital at Quito, ruled by Atahualpa, and the southern capital at Cusco, ruled by Atahualpa's brother Huáscar. Many of the Chachapoyas were conscripted into Huáscar's army, and heavy casualties ensued. After Atahualpa's eventual victory, many more of the Chachapoyas were executed or deported due to their former allegiance with Huáscar.

It was due to the harsh treatment of the Chachapoyas during the years of subjugation that many of the Chachapoyas initially chose to side with the Spanish colonialists when they arrived in Peru. Huaman, a local ruler from Quchapampa, pledged his allegiance to the conquistador Francisco Pizarro after the capture of Atahualpa in Cajamarca. The Spanish moved in and occupied Cochabamba, extorting from the local inhabitant whatever riches they could find.

During Manco Inca Yupanqui's rebellion against the Spanish Empire, his emissaries enlisted the help of a group of Chachapoyas. However, Guaman's supporters remained loyal to the Spanish. By 1547, a large faction of Spanish soldiers arrived in the city of Chachapoyas, effectively ending the Chachapoyas' independence. Residents were relocated to Spanish-style towns, often with members of several different ayllu occupying the same settlement. Disease, poverty, and attrition led to severe decreases in population; by some accounts the population of the Chachapoyas region decreased by 90% over the course of 200 years after the arrival of the Spanish.

Choquequirao, an Incan site in south Peru close to Machu Picchu, was in part built by mitmaqkuna of Chachapoyan origin during the regime of Tupac Inca Yupanqui.

Appearance and origins

Cieza de León remarked that, among the indigenous Peruvians, the Chachapoyas were unusually fair-skinned and famously beautiful:

They are the whitest and most handsome of all the people that I have seen in Indies, and their wives were so beautiful that because of their gentleness, many of them deserved to be the Incas' wives and to also be taken to the Sun Temple (...) The women and their husbands always dressed in woolen clothes and in their heads they wear their llautos, which are a sign they wear to be known everywhere.

These comments have led to claims, not supported by Cieza de León's chronicle, that the Chachapoyas were blond-haired and European in appearance. The chronicle's use of the term "white" here predates its emergence as a racial classification. Another Spanish author, Pedro Pizarro, described all indigenous Peruvians as "white." Although some authors have quoted Pizarro saying that Chachapoyas were blond, these authors do not quote him directly; instead they quote remarks attributed to him and others by race scientist Jacques de Mahieu in support of his thesis that Vikings had brought civilization to the Americas.[4][5] Following up on these claims, anthropologist Inge Schjellerup examined the remains of Chachapoyans and found them consistent with other ancient Peruvians. She found, for example, a universal occurrence of shovel-shaped upper incisors and a near-complete absence of the cusp of Carabelli on upper molars — characteristics consistent with other indigneous peoples and inconsistent with Europeans.[6]

According to the analysis of the Chachapoyas objects made by the Antisuyo expeditions of the Instituto de Arqueología Amazónica, the Chachapoyas do not exhibit Amazon cultural tradition but one more closely resembling an Andean one. Given that the terrain facilitates peripatric speciation, as evidenced by the high biodiversity of the Andean region, the physical attributes of the Chachapoyas are most likely reflecting founder effects, assortative mating, and/or related phenomena in an initially small population sharing a relatively recent common ancestor with other indigenous groups.

The anthropomorphous sarcophagi resemble imitations of funeral bundles provided with wooden masks typical of the "Middle Horizon", a dominant culture on the coast and highlands, also known as the Tiwanaku–Wari culture. The "mausoleums" may be modified forms of the chullpa or pucullo, elements of funeral architecture observed throughout the Andes, especially in the Tiwanaku and Wari cultures.

Population expansion into the Amazonian Andes seems to have been driven by the desire to expand agrarian land, as evidenced by extensive terracing throughout the region. The agricultural environments of both the Andes and the coastal region, characterized by its extensive desert areas and limited soil suitable for farming, became insufficient for sustaining a population like the ancestral Peruvians, which had grown for 3000 years.

This theory has been described as "mountainization of the rain forest" for both geographical and cultural reasons: first, after the fall of the tropical forests, the scenery of the Amazonian Andes changed to resemble the barren mountains of the Andes; second, the people who settled there brought their Andean culture with them. This phenomenon, which still occurs today, was repeated in the southern Amazonian Andes during the Inca Empire, which projected into the mountainous zone of Vilcabamba, raising examples of Inca architecture such as Machu Picchu.

Characteristics

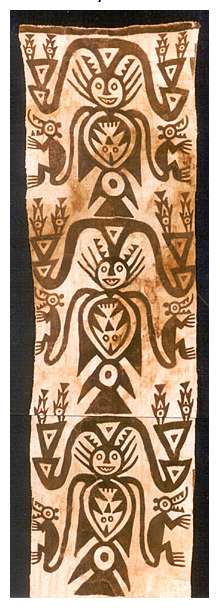

The architectural model of the Chachapoyas is characterized by circular stone constructions as well as raised platforms constructed on slopes. Their walls were sometimes decorated with symbolic figures. Some structures such as the monumental fortress of Kuelap and the ruins of Cerro Olán are prime examples of this architectural style.

Chachapoyan constructions may date to the 9th or 10th century; this architectural tradition still thrived at the time of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire until the latter part of the 16th century. To be sure, the Incas introduced their own style after conquering the Chachapoyas, such as in the case of the ruins of Quchapampa in Leimebamba District.

The presence of two funeral patterns is also typical of the Chachapoyas culture. One is represented by sarcophagi, placed vertically and located in caves that were excavated at the highest point of precipices. The other funeral pattern was groups of mausoleums constructed like tiny houses located in caves worked into cliffs.

Chachapoyan handmade ceramics did not reach the technological level of the Moche or Nazca cultures. Their small pitchers are frequently decorated by cordoned motifs. As for textile art, clothes were generally colored in red. A monumental textile from the precincts of Gran Pajatén had been painted with figures of birds. The Chachapoyas also used to paint their walls, as an extant sample in the tunnels of San Antonio in Luya Province reveals. These walls represent stages of a ritual dance of couples holding hands.

In popular culture

The Chachapoyan culture plays a significant role in the archaeological novel Inca Gold by Clive Cussler.

In the beginning scenes of the film Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones searches the booby-trapped ruins of a Chachapoyan temple for a golden idol.

See also

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- Extinct languages of the Marañón River basin#Chacha

- Machu Pirqa

- Purum Llaqta, Cheto

References

- ↑ "Diccionario Quechua - Aymara". www.katari.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- ↑ "Diccionario Quechua - Aymara". www.katari.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 2016-10-03.

- 1 2 3 Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 907. ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5.

- ↑ Ibarra Grasso, Dick Edgar (1997) Los Hombres Barbados en la América Precolombina p. 66

- ↑ Llanos, Oscar Olmedo (2006) Paranoia Aimara p. 182

- ↑ Schjellerup, Inge (1997) Incas and Spaniards in the Conquest of the Chachapoya

Further reading

- von Hagen, Adriana. An Overview of Chachapoya Archaeology and History from the Museo Leymebamba website.

- Hemming, John. Conquest of the Incas. Harcourt, 1970.

- Muscutt, Keith. Warriors of the Clouds. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1998.

- Savoy, Gene. Antisuyo: The Search for the Lost Cities of the Andes. Simon & Schuster, 1970.

- Schjellerup, Inge R. Incas and Spaniards in the Conquest of the Chachapoyas. Göteborg University, 1997.

- New Chachapoyan archaeological site discovered, September 16, 2010

- Giffhorn, Hans. Was America Discovered in Ancient Times?. C. H. Beck, 2013, 2nd revised edition March 2014. Published in the German Language as Wurde Amerika in der Antike entdeckt? Karthager, Kelten und das Rätsel der Chachapoya

- PBS TV Program Secrets of the Dead: Carthage's Lost Warriors. Single DVD, in English language.

External links

- Ethnography and Archaeology of Chachapoyas

- Chachapoyas: Cultural Development at a Cloud Forest Crossroads

- Tomb Raiders of El Dorado: Archaeological conservation dilemmas in Chachapoyas

- Peru North map including Chachapoyas