Teotihuacan

Coordinates: 19°41′33″N 98°50′37.68″W / 19.69250°N 98.8438000°W

|

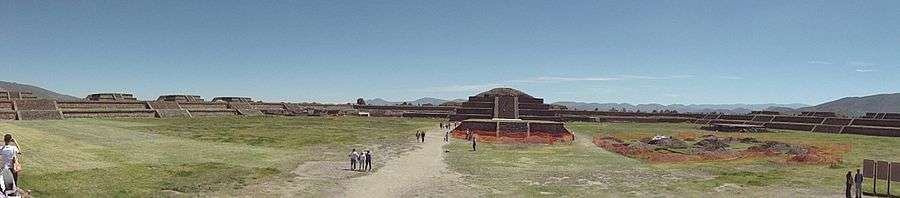

View of the Avenue of the Dead and the Pyramid of the Sun, from the Pyramid of the Moon. | |

Location of the site  Location of the site | |

| Location | Teotihuacán, State of Mexico, Mexico |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 19°41′33″N 98°50′37.68″W / 19.69250°N 98.8438000°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Late Preclassic to Late Classic |

| Official name | Pre-Hispanic City of Teotihuacan |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 414 |

| State Party |

|

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Teotihuacan /teɪˌoʊtiːwəˈkɑːn/,[1] also written Teotihuacán (Spanish pronunciation: [teotiwa'kan]), was an ancient Mesoamerican city located in a sub-valley of the Valley of Mexico, located in the State of Mexico 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast of modern-day Mexico City, known today as the site of many of the most architecturally significant Mesoamerican pyramids built in the pre-Columbian Americas.

At its zenith, perhaps in the first half of the 1st millennium AD, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas, with a population estimated at 125,000 or more, [2][3] making it at least the sixth largest city in the world during its epoch.[4]

Apart from the pyramids, Teotihuacan is also anthropologically significant for its complex, multi-family residential compounds; the Avenue of the Dead; and the small portion of its vibrant murals that have been exceptionally well-preserved. Additionally, Teotihuacan exported fine obsidian tools that garnered high prestige and widespread usage throughout Mesoamerica.[5]

The city is thought to have been established around 100 BC, with major monuments continuously under construction until about 250 AD.[2] The city may have lasted until sometime between the 7th and 8th centuries AD, but its major monuments were sacked and systematically burned around 550 AD.

Teotihuacan began as a new religious center in the Mexican Highlands around the first century AD. This city came to be the largest and most populated center in the pre-Columbian Americas. Teotihuacan was even home to multi-floor apartment compounds built to accommodate this large population.[2] The term Teotihuacan (or Teotihuacano) is also used for the whole civilization and cultural complex associated with the site.

Although it is a subject of debate whether Teotihuacan was the center of a state empire, its influence throughout Mesoamerica is well documented; evidence of Teotihuacano presence can be seen at numerous sites in Veracruz and the Maya region. The later Aztecs saw these magnificent ruins and claimed a common ancestry with the Teotihuacanos, modifying and adopting aspects of their culture. The ethnicity of the inhabitants of Teotihuacan is also a subject of debate. Possible candidates are the Nahua, Otomi, or Totonac ethnic groups. Scholars have also suggested that Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic state.

The city and the archaeological site are located in what is now the San Juan Teotihuacán municipality in the State of México, approximately 40 kilometres (25 mi) northeast of Mexico City. The site covers a total surface area of 83 square kilometres (32 sq mi) and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987. It is the most visited archaeological site in Mexico.

Name

The name Teōtīhuacān was given by the Nahuatl-speaking Aztecs centuries after the fall of the city around 550 A.D. The term has been glossed as "birthplace of the gods", or "place where gods were born",[6] reflecting Nahua creation myths that were said to occur in Teotihuacan. Nahuatl scholar Thelma D. Sullivan interprets the name as "place of those who have the road of the gods."[7] This is because the Aztecs believed that the gods created the universe at that site. The name is pronounced [te.oːtiːˈwakaːn] in Nahuatl, with the accent on the syllable wa. By normal Nahuatl orthographic conventions, a written accent would not appear in that position. Both this pronunciation and Spanish pronunciation: [te.otiwaˈkan] are used, and both spellings appear in this article.

The original name of the city is unknown, but it appears in hieroglyphic texts from the Maya region as puh, or "Place of Reeds".[8] This suggests that, in the Maya civilization of the Classic period, Teotihuacan was understood as a Place of Reeds similar to other Postclassic Central Mexican settlements that took the name of Tollan, such as Tula-Hidalgo and Cholula.

This naming convention led to much confusion in the early 20th century, as scholars debated whether Teotihuacan or Tula-Hidalgo was the Tollan described by 16th-century chronicles. It now seems clear that Tollan may be understood as a generic Nahua term applied to any large settlement. In the Mesoamerican concept of urbanism, Tollan and other language equivalents serve as a metaphor, linking the bundles of reeds and rushes that formed part of the lacustrine environment of the Valley of Mexico and the large gathering of people in a city.[9]

History

Origins and foundation

The early history of Teotihuacan is quite mysterious, and the origin of its founders is uncertain. Around 300 BC, people of the central and southeastern area of Mesoamerica began to gather into larger settlements.[10] Teotihuacan was the largest urban center of Mesoamerica before the Aztecs, almost 1000 years prior to their epoch.[10] The city was already in ruins by the time of the Aztecs. For many years, archaeologists believed it was built by the Toltec. This belief was based on colonial period texts, such as the Florentine Codex, which attributed the site to the Toltecs. However, the Nahuatl word "Toltec" generally means "craftsman of the highest level" and may not always refer to the Toltec civilization centered at Tula, Hidalgo. Since Toltec civilization flourished centuries after Teotihuacan, the people could not have been the city's founders.

In the Late Formative era, a number of urban centers arose in central Mexico. The most prominent of these appears to have been Cuicuilco, on the southern shore of Lake Texcoco. Scholars have speculated that the eruption of the Xitle volcano may have prompted a mass emigration out of the central valley and into the Teotihuacan valley. These settlers may have founded or accelerated the growth of Teotihuacan.

Other scholars have put forth the Totonac people as the founders of Teotihuacan. There is evidence that at least some of the people living in Teotihuacan immigrated from those areas influenced by the Teotihuacano civilization, including the Zapotec, Mixtec, and Maya peoples. The builders of Teotihuacan took advantage of the geography in the Basin of Mexico. From the swampy ground, they constructed raised beds, called chinampas. Creating high agricultural productivity despite old methods of cultivation.[10] This allowed for the formation of channels, and subsequently canoe traffic, to transport food from farms around the city. The earliest buildings at Teotihuacan date to about 200 BC. The largest pyramid, the Pyramid of the Sun, was completed by AD 100.[11]

Zenith

The city reached its peak in AD 450, when it was the center of a powerful culture whose influence extended through much of the Mesoamerican region. At its peak, the city covered over 30 km² (over 11 1⁄2 square miles), and perhaps housed a population of 150,000 people, with one estimate reaching as high as 250,000.[12] Various districts in the city housed people from across the Teotihuacano region of influence, which spread south as far as Guatemala. Notably absent from the city are fortifications and military structures.

The nature of political and cultural interactions between Teotihuacan and the centers of the Maya region (as well as elsewhere in Mesoamerica) has been a long-standing and significant area for debate. Substantial exchange and interaction occurred over the centuries from the Terminal Preclassic to the Mid-Classic period. "Teotihuacan-inspired ideologies" and motifs persisted at Maya centers into the Late Classic, long after Teotihuacan itself had declined.[13] However, scholars debate the extent and degree of Teotihuacano influence. Some believe that it had direct and militaristic dominance; others that adoption of "foreign" traits was part of a selective, conscious, and bi-directional cultural diffusion. New discoveries have suggested that Teotihuacan was not much different in its interactions with other centers from the later empires, such as the Toltec and Aztec.[14][15] It is believed that Teotihuacan had a major influence on the Preclassic and Classic Maya, most likely by conquering several Maya centers and regions, including Tikal and the region of Peten, and influencing Maya culture.

.jpg)

Architectural styles prominent at Teotihuacan are found widely dispersed at a number of distant Mesoamerican sites, which some researchers have interpreted as evidence for Teotihuacan's far-reaching interactions and political or militaristic dominance.[16] A style particularly associated with Teotihuacan is known as talud-tablero, in which an inwards-sloping external side of a structure (talud) is surmounted by a rectangular panel (tablero). Variants of the generic style are found in a number of Maya region sites, including Tikal, Kaminaljuyu, Copan, Becan, and Oxkintok, and particularly in the Petén Basin and the central Guatemalan highlands.[17] The talud-tablero style pre-dates its earliest appearance at Teotihuacan in the Early Classic period; it appears to have originated in the Tlaxcala-Puebla region during the Preclassic.[18] Analyses have traced the development into local variants of the talud-tablero style at sites such as Tikal, where its use precedes the 5th-century appearance of iconographic motifs shared with Teotihuacan. The talud-tablero style disseminated through Mesoamerica generally from the end of the Preclassic period, and not specifically, or solely, via Teotihuacano influence. It is unclear how or from where the style spread into the Maya region.[19]

The city was a center of industry, home to many potters, jewelers, and craftsmen. Teotihuacan is known for producing a great number of obsidian artifacts. No ancient Teotihuacano non-ideographic texts are known to exist (or known to have existed). Inscriptions from Maya cities show that Teotihuacan nobility traveled to, and perhaps conquered, local rulers as far away as Honduras. Maya inscriptions note an individual nicknamed by scholars as "Spearthrower Owl", apparently ruler of Teotihuacan, who reigned for over 60 years and installed his relatives as rulers of Tikal and Uaxactun in Guatemala.

Scholars have based interpretations about the culture at Teotihuacan on archaeology, the murals that adorn the site (and others, like the Wagner Murals, found in private collections), and hieroglyphic inscriptions made by the Maya describing their encounters with Teotihuacano conquerors. The creation of murals, perhaps tens of thousands of murals, reached its height between 450 and 650. The artistry of the painters was unrivaled in Mesoamerica and has been compared with that of painters in Renaissance Florence, Italy.[20]

Collapse

Scholars had thought that invaders attacked the city in the 7th or 8th century, sacking and burning it. More recent evidence, however, seems to indicate that the burning was limited to the structures and dwellings associated primarily with the ruling class. Some think this suggests that the burning was from an internal uprising. They say the invasion theory is flawed because early archaeological work on the city was focused exclusively on the palaces and temples, places used by the upper classes. Because all of these sites showed burning, archaeologists concluded that the whole city was burned. Instead, it is now known that the destruction was centered on major civic structures along the Avenue of the Dead. Some statues seem to have been destroyed in a methodical way, with their fragments dispersed.

Evidence for population decline beginning around the 6th century lends some support to the internal unrest hypothesis. The decline of Teotihuacan has been correlated to lengthy droughts related to the climate changes of 535–536. This theory of ecological decline is supported by archaeological remains that show a rise in the percentage of juvenile skeletons with evidence of malnutrition during the 6th century. This finding does not conflict with either of the above theories, since both increased warfare and internal unrest can also be effects of a general period of drought and famine.[21] Other nearby centers such as Cholula, Xochicalco, and Cacaxtla competed to fill the power void left by Teotihuacan's decline. They may have aligned themselves against Teotihuacan to reduce its influence and power. The art and architecture at these sites emulate Teotihuacan forms, but also demonstrate an eclectic mix of motifs and iconography from other parts of Mesoamerica, particularly the Maya region.

The sudden destruction of Teotihuacan is not uncommon for Mesoamerican city-states of the Classic and Epi-Classic period. Many Maya states suffered similar fates in the coming centuries, a series of events often referred to as the Classic Maya collapse. Nearby in the Morelos valley, Xochicalco was sacked and burned in 900 and Tula met a similar fate around 1150.[22]

Culture

Archaeological evidence suggests that Teotihuacan was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct quarters occupied by Otomi, Zapotec, Mixtec, Maya, and Nahua peoples. The Totonacs have always maintained that they were the ones who built it. The Aztecs repeated that story, but it has not been corroborated by archaeological findings.

In 2001, Terrence Kaufman presented linguistic evidence suggesting that an important ethnic group in Teotihuacan was of Totonacan or Mixe–Zoquean linguistic affiliation.[23] He uses this to explain general influences from Totonacan and Mixe–Zoquean languages in many other Mesoamerican languages, whose people did not have any known history of contact with either of the above-mentioned groups. Other scholars maintain that the largest population group must have been of Otomi ethnicity, because the Otomi language is known to have been spoken in the area around Teotihuacan both before and after the Classic period and not during the middle period.[24]

Religion

In their landmark 1992 volume, An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya, Miller and Taube list eight deities:[25]

- The Storm God[26]

- The Great Goddess

- The Feathered Serpent.[27] An important deity in Teotihuacan; most closely associated with the Feathered Serpent Pyramid.

- The Old God

- The War Serpent. Taube has differentiated two different serpent deities whose depictions alternate on the Feathered Serpent Pyramid: the Feathered Serpent and what he calls the "War Serpent". Other researchers are more skeptical.[28]

- The Netted Jaguar

- The Pulque God

- The Fat God. Known primarily from figurines and so assumed to be related to household rituals.[29]

Esther Pasztory adds one more:[30]

- The Flayed God. Known primarily from figurines and so assumed to be related to household rituals.[29]

.jpg)

The consensus among scholars is that the primary deity of Teotihuacan was the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan.[31] The dominant civic architecture is the pyramid. Politics were based on the state religion; religious leaders were the political leaders.[32]

Teotihuacanos practiced human sacrifice: human bodies and animal sacrifices have been found during excavations of the pyramids at Teotihuacan. Scholars believe that the people offered human sacrifices as part of a dedication when buildings were expanded or constructed. The victims were probably enemy warriors captured in battle and brought to the city for ritual sacrifice to ensure the city could prosper.[33] Some men were decapitated, some had their hearts removed, others were killed by being hit several times over the head, and some were buried alive. Animals that were considered sacred and represented mythical powers and military were also buried alive, imprisoned in cages: cougars, a wolf, eagles, a falcon, an owl, and even venomous snakes.[34]

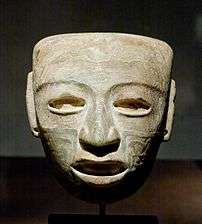

Numerous stone masks have been found at Teotihuacan, and have been generally believed to have been used during a funerary context,[35] although some scholars call this into question, noting that masks "do not seem to have come from burials".[36]

Residency

Teotihuacan was a mix of residential and work areas. Upper-class homes were usually compounds that housed many such families, and one compound was found that was capable of housing between sixty and eighty families. Such superior residences were typically made of plaster, each wall in every section elaborately decorated with murals. These compounds or apartment complexes were typically found within the city center. The vast lakes of the Basin of Mexico provided the opportunity for people living around them to construct productive raised beds, or chinampas, from swampy muck, construction that also produced channels between the beds.

Different sections of the city housed particular ethnic groups and immigrants. Typically, these sections of the city were speaking multiple languages.

Archaeological site

Knowledge of the huge ruins of Teotihuacan was never completely lost. After the fall of the city, various squatters lived on the site. During Aztec times, the city was a place of pilgrimage and identified with the myth of Tollan, the place where the sun was created. Today, Teotihuacan is one of the most noted archaeological attractions in Mexico.

Excavations and investigations

In the late 17th century Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645–1700) made some excavations around the Pyramid of the Sun.[37] Minor archaeological excavations were conducted in the 19th century. In 1905 the archaeologist Leopoldo Batres[38] led a major project of excavation and restoration. The Pyramid of the Sun was restored to celebrate the centennial of the Mexican War of Independence in 1910. Further excavations at the Ciudadela were carried out in the 1920s, supervised by Manuel Gamio. Other sections of the site were excavated in the 1940s and 1950s. The first site-wide project of restoration and excavation was carried out by INAH from 1960 to 1965, supervised by Jorge Acosta. This undertaking had the goals of clearing the Avenue of the Dead, consolidating the structures facing it, and excavating the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl.

During the installation of a "sound and light" show in 1971, workers discovered the entrance to a tunnel and cave system underneath the Pyramid of the Sun.[39] Although scholars long thought this to be a natural cave, more recent examinations have established the tunnel was entirely manmade.[40] The interior of the Pyramid of the Sun has never been fully excavated.

In 1980-82, another major program of excavation and restoration was carried out at the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent and the Avenue of the Dead complex. Most recently, a series of excavations at the Pyramid of the Moon have greatly expanded evidence of cultural practices.

In 2005, a three hundred and thirty foot long tunnel was discovered underneath the pyramid after rainfall uncovered an entrance adjacent to it. Several side-chambers were also discovered. The tunnel and chambers were explored in 2013 with a remote control robot named Tlaloc II-TC, supervised by archaeologist Sergio Gómez Chávez, the director of the Tlalocan Project. In one of the side chambers, the robot discovered strange Yellow spheres of Teotihuacan made of a core of clay covered in Jarosite formed by oxidation of pyrite. It is suggested the spheres were once metallic and would have shone with a brilliant luster. George Cowgill from Arizona State University commented, "They are indeed unique, but I have no idea what they mean." Other finds in the underground section of the pyramid included masks covered in crystals such as quartz and jade along with pottery dating from around AD 100. The team continues to explore further into the tunnel, encouraged by these promising results.[41]

In November, 2014 "large quantities" of mercury were discovered in a chamber 60 feet below the 1800 year-old pyramid known as the "Temple of the Feathered Serpent," "the third largest pyramid of Teotihuacan," along with "jade statues, jaguar remains, a box filled with carved shells and rubber balls."[42]

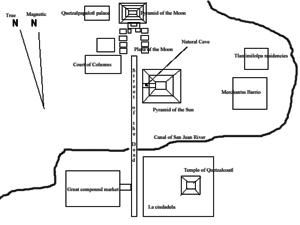

Site layout

The city's broad central avenue, called "Avenue of the Dead" (a translation from its Nahuatl name Miccoatli), is flanked by impressive ceremonial architecture, including the immense Pyramid of the Sun (third largest in the World after the Great Pyramid of Cholula and the Great Pyramid of Giza). Along the Avenue of the Dead are many smaller talud-tablero platforms. The Aztecs believed they were tombs, inspiring the name of the avenue. Scholars have now established that these were ceremonial platforms that were topped with temples.

Further down the Avenue of the Dead is the area known as the Citadel, containing the ruined Temple of the Feathered Serpent. This area was a large plaza surrounded by temples that formed the religious and political center of the city. The name "Citadel" was given to it by the Spanish, who believed it was a fort. Most of the common people lived in large apartment buildings spread across the city. Many of the buildings contained workshops where artisans produced pottery and other goods.

The geographical layout of Teotihuacan is a good example of the Mesoamerican tradition of planning cities, settlements, and buildings as a representation of the view of the Universe. Its urban grid is aligned to precisely 15.5º east of North. One theory says this is due to the fact that the sun rose at that same angle during the same summer day each year. Settlers used the alignment to calibrate their sense of time or as a marker for planting crops or performing certain rituals. Another theory is that there are numerous ancient sites in Mesoamerica that seem to be oriented with the tallest mountain in their given area. This appears to be the case at Teotihuacan, although the mountain to which it is oriented is not visible from within the Teotihuacan complex due to a closer mountain ridge.[43] Pecked-cross circles throughout the city and in the surrounding regions indicate how the people managed to maintain the urban grid over long distances. It also enabled them to orient the Pyramids to the distant mountain that was out of sight.

The Ciudadela was completed during the Miccaotli phase, and the Pyramid of the Sun underwent a complex series of additions and renovations. The Great Compound was constructed across the Avenue of the Dead, west of Ciudadela. This was probably the city’s marketplace. The existence of a large market in an urban center of this size is strong evidence of state organization. Teotihuacan was at that point simply too large and too complex to have been politically viable as a chiefdom.

The Ciudadela is a great enclosed compound capable of holding 100,000 people. About 700,000 cubic meters (yards) of material was used to construct its buildings. Its central feature is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, which was flanked by upper class apartments. The entire compound was designed to overwhelm visitors.

Threat from development

The archaeological park of Teotihuacan is under threat from development pressures. In 2004, the governor of Mexico state, Arturo Montiel, gave permission for Wal-Mart to build a large store in the third archaeological zone of the park. According to Counterpunch.org, "[P]riceless artifacts uncovered during store construction were reportedly trucked off to a local dump and workers fired when they revealed the carnage to the press."[44]

More recently, Teotihuacan has become the center of controversy over Resplandor Teotihuacano, a massive light and sound spectacular installed to create a night time show for tourists.[45][46] Critics explain that the large number of perforations for the project have caused fractures in stones and irreversible damage, while the project will have limited benefit.

Gallery

-

Front view of the Pyramid of the Sun

-

Left side view of the Pyramid of the Sun

-

Courtyard of the Palacio de Quetzalpapálotl

-

Terracotta figurines

-

Jaguar mural

-

Marble mask, 3rd - 7th century

-

Serpentine mask, 3rd-6th century

-

Alabaster statue of an Ocelot from Teotihuacan, 5th-6th century, possibly a ritual container to receive sacrificed human hearts (British Museum)[1]

-

Detail of a collective burial of those slaughtered as part of the rites of consecration for the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (phase Miccaotli, c. 200 A.C.) In this case, all buried bodies had their hands tied behind their backs. The necklace is made of pieces that simulate human jaws, but other subjects buried wore necklaces with actual jaws.

-

Detail of the murals of the palace of Atetelco, dated in Xolalpan phase ( c. 450-650).

See also

- Cerro de la Estrella, a large Teotihuacano-styled pyramid in what is now part of Mexico City

- List of archaeoastronomical sites by country

- List of megalithic sites

- List of Mesoamerican pyramids

- List of World Heritage Sites in Mexico

- Robert E. Lee Chadwick, an American anthropologist and archeologist

- Spring equinox in Teotihuacán

References

Notes

- ↑ "Teotihuacán". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Teotihuacan". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Department of Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Millon, p. 18.

- ↑ Millon, p. 17, who says it was the sixth largest city in the world in AD 600.

- ↑ Ancient Mexico and Central America

- ↑ Archaeology of Native North America by Dean R. Snow.

- ↑ Millon (1993), p.34.

- ↑ Mathews and Schele (1997, p.39)

- ↑ Miller and Taube (1993, p.170)

- 1 2 3 Pollard, Elizabeth; Rosenberg, Clifford; Tignor, Robert (2015). Worlds Together Worlds Apart Volume 1 Concise Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ↑ Millon (1993), p.24.

- ↑ Malmström (1978, p.105) gives an estimate of 50,000 to 200,000 inhabitants. Coe et al. (1986) says it "might lie between 125,000 and 250,000". Millon, p. 18, lists 125,000 in AD 600. Taube, p. 1, says "perhaps as many as 150,000".

- ↑ Braswell (2003, p.7)

- ↑ "Mexico's Pyramid of Death". National Geographic. 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ "Sacrificial Burial Deepens Mystery At Teotihuacan, But Confirms The City's Militarism". ScienceDaily. 2004. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ See for example Cheek (1977, passim.), who argues that much of Teotihuacan's influence stems from direct militaristic conquest.

- ↑ See Laporte (2003, p.205); Varela Torrecilla and Braswell (2003, p.261).

- ↑ Braswell (2003, p.11)

- ↑ Braswell (2003, p.11); for the analysis at Tikal, see Laporte (2003, pp.200–205)

- ↑ Davies, p. 78.

- ↑ Kaufman (2001, p.4)

- ↑ Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Prentice Hall. p. 156.

- ↑ Terrence Kaufman, "Nawa linguistic prehistory", SUNY Albany

- ↑

- Wright Carr; David Charles (2005). "El papel de los otomies en las culturas del altiplano central 5000 a.C - 1650 d.C". Arqueología mexicana (in Spanish). XIII (73): 19.

- ↑ Miller & Taube, pp. 162–63.

- ↑ Instead of "Storm God", Miller and Taube call this deity "Tlaloc", the name of the much later Aztec storm god. Coe (1994), p. 101, uses the same term. However, the use of Nahuatl Aztec names to denote Teotihuacan deities has been in decline (see Berlo, p. 147).

- ↑ Instead of "the Feathered Serpent", Miller and Taube call this deity "Quetzalcoatl", the name of the much later Aztec feathered serpent god.

- ↑ Sugiyama (1992), p. 220.

- 1 2 Pasztory (1997), p. 84.

- ↑ Pasztory (1997), pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Cowgill (1997), p. 149. Pasztory (1992), p. 281.

- ↑ Sugiyama, p. 111.

- ↑ Coe (1994), p. 98.

- ↑ Sugiyama: 109, 111

- ↑ Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. Birmingham, AL: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- ↑ Pasztory (1993), p. 54.

- ↑ Tunnel under Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent under exploration in 2010

- ↑ es:Leopoldo Batres

- ↑ Heyden (1975, p.131)

- ↑ Šprajc (2000), p. 410

- ↑ Rossella Lorenzi, Discovery.com, Robot finds mysterious spheres in ancient temple, 1/5/13

- ↑ Alan Yuhas, Liquid mercury found under Mexican pyramid could lead to king's tomb, The Guardian, April 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Teotihuacan History".

- ↑ Ross, John (February 27 – March 1, 2009). "Teotihuacan Gets Mickey-Moused". Counterpunch.org Weekend Edition.

- ↑ Prensa Latina, Protesters Demand Stop on Pyramid Project, Banderas News, February 2009.

- ↑ Prensa Latina, Tourists reject sound and light show at Mexican pyramids, TwoCircles.net, February 18, 2009.

Bibliography

- Berrin, Kathleen; Esther Pasztory (1993). Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-23653-4. OCLC 28423003.

- Braswell, Geoffrey E. (2003). "Introduction: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction". In Geoffrey E. Braswell. The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 1–44. ISBN 0-292-70587-5. OCLC 49936017.

- Brown, Dale M., ed. (1992). Aztecs: Reign of Blood and Splendor. Lost Civilizations series. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-9854-5. OCLC 24848419.

- Cheek, Charles D. (1977). "Excavations at the Palangana and the Acropolis, Kaminaljuyu". In William T. Sanders; Joseph W. Michels. Teotihuacan and Kaminaljuyu: a Study in Prehistoric Culture Contact. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 1–204. ISBN 0-271-00529-7. OCLC 3327234.

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (1994) [1962]. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27722-2. OCLC 50131575.

- Coe, Michael D.; Dean Snow; Elizabeth Benson (1986). Atlas of Ancient America. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-1199-0.

- Cowgill, George L. (1992). "Teotihuacan Glyphs and Imagery in the Light of Some Early Colonial Texts". In Janet Catherine Berlo. Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 8th and 9th October 1988. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 231–46. ISBN 0-88402-205-6. OCLC 25547129.

- Cowgill, George (1997). "State and Society at Teotihuacan, Mexico" (PDF online reproduction). Annual Review of Anthropology. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews Inc. 26 (1): 129–161. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129. OCLC 202300854.

- Davies, Nigel (1982). The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. England: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-013587-1.

- Heyden, Doris (1975). "An Interpretation of the Cave underneath the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan, Mexico". American Antiquity. Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology. 40 (2): 131–147. doi:10.2307/279609. JSTOR 279609. OCLC 1479302.

- Kaufman, Terrence (2001). "Nawa linguistic prehistory". Mesoamerican Language Documentation Project.

- Laporte, Juan Pedro (2003). "Architectural Aspects of Interaction Between Tikal and Teotihuacan during the Early Classic Period". In Geoffrey E. Braswell. The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 199–216. ISBN 0-292-70587-5. OCLC 49936017.

- Malmström, Vincent H. (1978). "Architecture, Astronomy, and Calendrics in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica" (PDF Reprinted). Journal for the History of Astronomy. 9: 105–116. Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05068-6. OCLC 27667317.

- Millon, René (1993). "The Place Where Time Began: An Archaeologist's Interpretation of What Happened in Teotihuacan History". In Berrin, Kathleen; Esther Pasztory. Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods. New York: Thames and Hudson. pp. 16–43. ISBN 0-500-23653-4. OCLC 28423003.

- Pasztory, Esther (1992). "Abstraction and the rise of a utopian state at Teotihuacan", in Janet Berlo, ed. Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan, Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 281-320.

- Schele, Linda; Peter Mathews (1998). The Code of Kings: The Language of Seven Sacred Maya Temples and Tombs. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80106-X. OCLC 37819972.

- Sugiyama, Saburo (2003). Governance and Polity at Classic Teotihuacan; in Julia Ann Hendon, Rosemary A. Joyce, "Mesoamerican archaeology". Wiley-Blackwell.

- Séjourné, Laurette,Un Palacio en la ciudad de los dioses, Teotihuacán, Mexico, Instituto nacional de antropología e historia, 1959.

- Séjourné, Laurette (1962) El Universo de Quetzalcóatl, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Séjourné, Laurette (1966) Arqueología de Teotihuacán, la cerámica, Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- Séjourné, Laurette (1969) Teotihuacan, métropole de l'Amérique, Paris, F. Maspero.

- Šprajc, Ivan; Sprajc, Ivan (2000). "Astronomical Alignments at Teotihuacan, Mexico". Latin American Antiquity. Washington, DC: Society for American Archaeology. 11 (4): 403–415. doi:10.2307/972004. JSTOR 972004.

- Taube, Karl A. (2000). The Writing System of Ancient Teotihuacan (PDF). Ancient America series. 1. Barnardsville, NC: Center for Ancient American Studies. OCLC 44992821.

- Varela Torrecilla, Carmen; Geoffrey E. Braswell (2003). "Teotihuacan and Oxkintok: New Perspectives from Yucatán". In Geoffrey E. Braswell. The Maya and Teotihuacan: Reinterpreting Early Classic Interaction. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 249–72. ISBN 0-292-70587-5. OCLC 49936017.

- Weaver, Muriel Porter (1993). The Aztecs, Maya, and Their Predecessors: Archaeology of Mesoamerica (3rd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-01-263999-0.

- Webmoor, Timothy (2007). "Reconfiguring the Archaeological Sensibility: Mediating Heritage at Teotihuacan, Mexico" (online digital publication). Symmetrical Archaeology [2005–, collaboratory directors T. Webmoor and C. Witmore]. PhD thesis. Stanford Archaeology Center/Metamedia Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teotihuacán. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Teotihuacan. |

- Teotihuacan Research Guide, academic resources and links, maintained by Temple University

- Teotihuacan Teotihuacan information and history

- Teotihuacan article by Encyclopædia Britannica

- Teotihuacan Photo Gallery, by James Q. Jacobs

- 360° Panoramic View of the Avenue of the Dead, the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon , by Roland Kuczora