Click chemistry

In chemical synthesis, "click" chemistry, more commonly called tagging, is a class of biocompatible reactions intended primarily to join substrates of choice with specific biomolecules. Click chemistry is not a single specific reaction, but describes a way of generating products that follows examples in nature, which also generates substances by joining small modular units. In general, click reactions usually join a biomolecule and a reporter molecule. Click chemistry is not limited to biological conditions: the concept of a "click" reaction has been used in pharmacological and various biomimetic applications. However, they have been made notably useful in the detection, localization and qualification of biomolecules.

Click reactions occur in one pot, are not disturbed by water, generate minimal and inoffensive byproducts, and are "spring-loaded"—characterized by a high thermodynamic driving force that drives it quickly and irreversibly to high yield of a single reaction product, with high reaction specificity (in some cases, with both regio- and stereo-specificity). These qualities make click reactions particularly suitable to the problem of isolating and targeting molecules in complex biological environments. In such environments, products accordingly need to be physiologically stable and any byproducts need to be non-toxic (for in vivo systems).

By developing specific and controllable bioorthogonal reactions, scientists have opened up the possibility of hitting particular targets in complex cell lysates. Recently, scientists have adapted click chemistry for use in live cells, for example using small molecule probes that find and attach to their targets by click reactions. Despite challenges of cell permeability, bioorthogonality, background labeling, and reaction efficiency, click reactions have already proven useful in a new generation of pulldown experiments (in which particular targets can be isolated using, for instance, reporter molecules which bind to a certain column), and fluorescence spectrometry (in which the fluorophore is attached to a target of interest and the target quantified or located). More recently, novel methods have been used to incorporate click reaction partners onto and into biomolecules, including the incorporation of unnatural amino acids containing reactive groups into proteins and the modification of nucleotides. These techniques represent a part of the field of chemical biology, in which click chemistry plays a fundamental role by intentionally and specifically coupling modular units to various ends.

The term "click chemistry" was coined by K. Barry Sharpless in 1998, and was first fully described by Sharpless, Hartmuth Kolb, and M.G. Finn of The Scripps Research Institute in 2001.[1][2]

Background

Click chemistry is a method for attaching a probe or substrate of interest to a specific biomolecule, a process called bioconjugation. The possibility of attaching fluorophores and other reporter molecules has made click chemistry a very powerful tool for identifying, locating, and characterizing both old and new biomolecules.

One of the earliest and most important methods in bioconjugation was to express a reporter on the same open reading frame as a biomolecule of interest. Notably, GFP was first (and still is) expressed in this way at the N- or C- terminus of many proteins. However, this approach comes with several difficulties. For instance, GFP is a very large unit and can often affect the folding of the protein of interest. Moreover, by being expressed at either terminus, the GFP adduct can also affect the targeting and expression of the desired protein. Finally, using this method, GFP can only be attached to proteins, and not post-translationally, leaving other important biomolecular classes (nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates, etc.) out of reach.

To overcome these challenges, chemists have opted to proceed by identifying pairs of bioorthogonal reaction partners, thus allowing the use of small exogenous molecules as biomolecular probes. A fluorophore can be attached to one of these probes to give a fluorescence signal upon binding of the reporter molecule to the target—just as GFP fluoresces when it is expressed with the target.

Now limitations emerge from the chemistry of the probe to its target. In order for this technique to be useful in biological systems, click chemistry must run at or near biological conditions, produce little and (ideally) non-toxic byproducts, have (preferably) single and stable products at the same conditions, and proceed quickly to high yield in one pot. Existing reactions, such as Staudinger ligation and the Huisgen 1,3–dipolar cycloaddition, have been modified and optimized for such reaction conditions. Today, research in the field concerns not only understanding and developing new reactions and repurposing and re-understanding known reactions, but also expanding methods used to incorporate reaction partners into living systems, engineering novel reaction partners, and developing applications for bioconjugation.

Reactions

According to Sharpless, a desirable click chemistry reaction would:[1]

- be modular

- be wide in scope

- give very high chemical yields

- generate only inoffensive byproducts

- be stereospecific

- be physiologically stable

- exhibit a large thermodynamic driving force (> 84 kJ/mol) to favor a reaction with a single reaction product. A distinct exothermic reaction makes a reactant "spring-loaded".

- have high atom economy.

The process would preferably:

- have simple reaction conditions

- use readily available starting materials and reagents

- use no solvent or use a solvent that is benign or easily removed (preferably water)

- provide simple product isolation by non-chromatographic methods (crystallisation or distillation)

Many of the click chemistry criteria are subjective, and even if measurable and objective criteria could be agreed upon, it is unlikely that any reaction will be perfect for every situation and application. However, several reactions have been identified that fit the concept better than others:

- [3+2] cycloadditions, such as the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition, in particular the Cu(I)-catalyzed stepwise variant,[3] are often referred to simply as Click reactions

- Thiol-ene reaction[4][5]

- Diels-Alder reaction and inverse electron demand Diels-Alder reaction[6]

- [4+1] cycloadditions between isonitriles (isocyanides) and tetrazines[7]

- nucleophilic substitution especially to small strained rings like epoxy [8] and aziridine compounds

- carbonyl-chemistry-like formation of ureas but not reactions of the aldol type due to low thermodynamic driving force.

- addition reactions to carbon-carbon double bonds like dihydroxylation or the alkynes in the thiol-yne reaction.

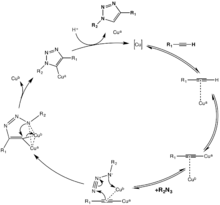

Copper(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC)

The classic[9][10] click reaction is the Copper-catalyzed reaction of an azide with an alkyne to form a 5-membered heteroatom ring: a Cu(I)-Catalyzed Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC). The first triazole synthesis, from diethyl acetylenedicarboxylate and phenyl azide, was reported by Arthur Michael in 1893.[11] Later, in the middle of the 20th century, this family of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions took on Huisgen’s name after his studies of their reaction kinetics and conditions.

The Copper(I)-catalysis of the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition was discovered concurrently and independently by the groups of Valery V. Fokin and K. Barry Sharpless at the Scripps Research Institute in California[12] and Morten Meldal in the Carlsberg Laboratory, Denmark.[13] The copper-catalyzed version of this reaction gives only the 1,4-isomer, whereas Huisgen’s non-catalyzed 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition gives both the 1,4- and 1,5-isomers, is slow, and requires a temperature of 100 degrees Celsius.[11]

Moreover, this copper-catalyzed “click” does not require ligands on the metal, although accelerating ligands such as Tris(triazolyl)methyl amine ligands with various substituents have been reported and used with success in aqueous solution.[11] Other ligands such as PPh3 and TBIA can also be used, even though PPh3 is liable to Staudinger ligation with the azide substituent. Cu2O in water at room temperature was found also to catalyze the same reaction in 15 minutes with 91% yield.[14]

The first reaction mechanism proposed included one catalytic copper atom, but isotope studies have suggested the contribution of two functionally distinct Cu atoms in the CuAAC mechanism.[15] Even though this reaction proceeds effectively at biological conditions, copper in this range of dosage is cytotoxic. Solutions to this problem have been presented, such as using water-soluble ligands on the copper to enhance cell penetration of the catalyst and thereby reduce the dosage needed,[16] or to use chelating ligands to further increase the effective concentration of Cu(I) and thereby decreasing the actual dosage.[17]

Although the Cu(I)-catalyzed variant was first reported by Meldal and co-workers for the synthesis of peptidotriazoles on solid support, they needed more time to discover the full scope of the reaction and were overtaken by the publicly more recognized Sharpless. Meldal and co-workers also chose not to label this reaction type "click chemistry" which allegedly caused their discovery to be largely overlooked by the mainstream chemical society. Sharpless and Fokin independently described it as a reliable catalytic process offering "an unprecedented level of selectivity, reliability, and scope for those organic synthesis endeavors which depend on the creation of covalent links between diverse building blocks."

An analogous RuAAC reaction catalyzed by ruthenium, instead of copper, was reported by the Sharpless group in 2005, and allows for the selective production of 1,5-isomers.[18]

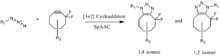

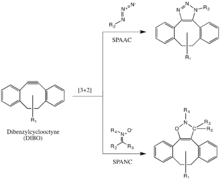

Strain-promoted Azide-Alkyne Cycloaddition (SPAAC)

The Bertozzi group further developed one of Huisgen’s copper-free click reactions to overcome the cytotoxicity of the CuAAC reaction.[19] Instead of using Cu(I) to activate the alkyne, the alkyne is instead introduced in a strained difluorooctyne (DIFO), in which the electron-withdrawing, propargylic, gem-fluorines act together with the ring strain to greatly destabilize the alkyne.[20] This destabilization increasing the reaction driving force, and the desire of the cycloalkyne to relieve its ring strain.

This reaction proceeds as a concerted [3+2] cycloaddition in the same mechanism as the Huisgen 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition. Substituents other than fluorines, such as benzene rings, are also allowed on the cyclooctyne.

This reaction has been used successfully to probe for azides in living systems, even though the reaction rate is somewhat slower than that of the CuAAC. Moreover, because the synthesis of cyclooctynes often gives low yield, probe development for this reaction has not been as rapid as for other reactions. But cyclooctyne derivatives such as DIFO, dibenzylcyclooctyne (DIBO) and biarylazacyclooctynone (BARAC) have all been used successfully in the SPAAC reaction to probe for azides in living systems.[21]

Strain-promoted Alkyne-Nitrone Cycloaddition (SPANC)

Diaryl-strained-cyclooctynes including dibenzylcyclooctyne (DIBO) have also been used to react with 1,3-nitrones in strain-promoted alkyne-nitrone cycloadditions (SPANC) to yield N-alkylated isoxazolines.[22]

Because this reaction is metal-free and proceeds with fast kinetics (k2 as fast as 60 1/Ms, faster than both the CuAAC or the SPAAC) SPANC can be used for live cell labeling. Moreover, substitution on both the carbon and nitrogen atoms of the nitrone dipole, and acyclic and endocyclic nitrones are all tolerated. This large allowance provides a lot of flexibility for nitrone handle or probe incorporation.[23]

However, the isoazoline product is not as stable as the triazole product of the CuAAC and the SpAAC, and can undergo rearrangements at biological conditions. Regardless, this reaction is still very useful as it has notably fast reaction kinetics.[24]

The applications of this reaction include labeling proteins containing serine as the first residue: the serine is oxidized to aldehyde with NaIO4 and then converted to nitrone with p-methoxybenzenethiol, N-methylhydroxylamine and p-ansidine, and finally incubated with Cyclooctyne to give a click product. The SPANC also allows for multiplex labeling.[25]

Reactions of Strained Alkenes

Strained alkenes also utilize strain-relief as a driving force that allows for their participation in click reactions. Trans-cycloalkenes (usually cyclooctenes) and other strained alkenes such as oxanorbornadiene react in click reactions with a number of partners including Azides, Tetrazines and Tetrazoles. These reaction partners can interact specifically with the strained alkene, staying bioorthogonal to endogenous alkenes found in lipids, fatty acids, cofactors and other natural products.[26]

Alkene and Azide [3+2] cycloaddition

Oxanorbornadiene (or another activated alkene) reacts with azides, giving triazoles as a product. However, these product triazoles are not aromatic as they are in the CuAAC or SPAAC reactions, and as a result are not as stable. The activated double bond in oxanobornadiene makes a triazoline intermediate that subsequently spontaneously undergoes a retro Diels-alder reaction to release furan and give 1,2,3- or 1,4,5-triazoles. Even though this reaction is slow, it is useful because oxabornodiene is relatively simple to synthesize. The reaction is not, however, entirely chemoselective.[27]

Alkene and Tetrazine inverse-demand Diels-Alder

Strained cyclooctenes and other activated alkenes react with tetrazines in an inverse electron-demand Diels-Alder followed by a retro [4+2] cycloaddition (see figure).[28] Like the other reactions of the trans-cyclooctene, ring strain release is a driving force for this reaction. Thus, three-membered and four-membered cycloalkenes, due to their high ring strain, make ideal alkene substrates.[28]

Similar to other [4+2] cycloadditions, electron-donating substituents on the dienophile and electron-withdrawing substituents on the diene accelerate the inverse-demand diels-alder. The diene, the tetrazine, by virtue of having the additional nitrogens, is a good diene for this reaction. The dienophile, the activated alkene, can often be attached to electron-donating alkyl groups on target molecules, thus making the dienophile more suitable for the reaction.[29]

Alkene and Tetrazole photoclick reaction

The Tetrazole-alkene “photoclick” reaction is another dipolar addition that Husigen first introduced about 50 years ago (ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 1504. (68) Clovis, J. S.; Eckell, A.; Huisgen, R.; Sustmann, R. Chem. Ber. 1967, 100, 60.) Tetrazoles with amino or styryl groups that can be activated by UV light at 365 nm (365 does not damage cells) react quickly (so that the UV light does not have to be on for a long time, usually around 1–4 minutes) to make fluorogenic pyrazoline products. This reaction scheme is well suited for the purpose of labeling in live cells, because UV light at 365 nm damages cells minimally. Moreover, the reaction proceeds quickly, so that the UV light can be administered for short durations. Finally, the non-fluorogenic reactants give rise to a fluorogenic product, equipping the reaction with a built-in spectrometry handle.

Both tetrazoles and the alkene groups have been incorporated as protein handles as unnatural amino acids, but this benefit is not unique. Instead, the photoinducibility of the reaction makes it a prime candidate for spatiotemporal specificity in living systems. Challenges include the presence of endogenous alkenes, though usually cis (as in fatty acids) they can still react with the activated tetrazole.[30]

Applications

The applications of click chemistry are broad in that they allow for the attachment of a wide range of probes to a wide range of biomolecule targets. Several notable applications of click chemistry include the attachment of fluorescent probes for spectrometric quantification and qualification, and of handle molecules that allow for purification of the target biomolecule. For example, fluorophores such as rhodamine have been coupled onto norbonene, and reacted with tetrazine in living systems.[31] In other cases, SPAAC between a cyclooctyne-modified fluorophore and azide-tagged proteins allowed the selection of these proteins in cell lysates.[32]

In addition, novel methods for the incorporation of click reaction partners into systems in and ex vivo contribute to the scope of possible reactions. The development of unnatural amino acid incorporation by ribosomes has allowed for the incorporation of click reaction partners as unnatural side groups on these unnatural amino acids. For example, an UAA with an azide side group provides convenient access for cycloalkynes to proteins tagged with this “AHA” unnatural amino acid.[33] In another example, “CpK” has a side group including a cyclopropane alpha to an amide bond that serves as a reaction partner to tetrazine in an inverse diels-alder reaction.[34]

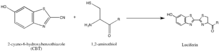

The synthesis of luciferin exemplifies another strategy of isolating reaction partners, which is to take advantage of rarely-occurring, natural groups such as the 1,2-aminothiol, which appears only when a cysteine is the final N’ amino acid in a protein. Their natural selectivity and relative bioorthogonality is thus valuable in developing probes specific for these tags. The above reaction occurs between a 1,2-aminothiol and a 2-cyanobenzothiazole to make luciferin, which is fluorescent. This luciferin fluorescence can be then quantified by spectrometry following a wash, and used to determine the relative presence of the molecule bearing the 1,2-aminothiol. If the quantification of non-1,2-aminothiol-bearing protein is desired, the protein of interest can be cleaved to yield a fragment with a N’ Cys that is vulnerable to the 2-CBT.[35]

Additional applications include:

- Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis separation[36]

- preparative organic synthesis of 1,4-substituted triazoles

- modification of peptide function with triazoles

- modification of natural products and pharmaceuticals

- natural product discovery [37]

- drug discovery

- macrocyclizations using Cu(I) catalyzed triazole couplings

- modification of DNA and nucleotides by triazole ligation

- supramolecular chemistry: calixarenes, rotaxanes, and catenanes

- dendrimer design

- carbohydrate clusters and carbohydrate conjugation by Cu(1) catalyzed triazole ligation reactions

- Polymers and Biopolymers [38]

- surfaces[39]

- material science

- nanotechnology,[40] and

- Bioconjugation, for example, azidocoumarin.

- Biomaterials[41]

In combination with combinatorial chemistry, high-throughput screening, and building chemical libraries, click chemistry has sped up new drug discoveries by making each reaction in a multistep synthesis fast, efficient, and predictable.

Technology license

The Scripps Research Institute has a portfolio of click-chemistry patents.[42] Licensees include Invitrogen,[43] Allozyne,[44] Aileron,[45] Integrated Diagnostics,[46] and the biotech company baseclick, a BASF spin-off created to sell products made using click chemistry.[47] Moreover, baseclick holds a worldwide exclusive license for the research and diagnostic market for the nucleic acid field. Fluorescent azides and alkynes also produced by such companies as Active Motif Chromeon[48] and Cyandye

References

- 1 2 H. C. Kolb; M. G. Finn; K. B. Sharpless (2001). "Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (11): 2004–2021. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 11433435.

- ↑ R. A. Evans (2007). "The Rise of Azide–Alkyne 1,3-Dipolar 'Click' Cycloaddition and its Application to Polymer Science and Surface Modification". Australian Journal of Chemistry. 60 (6): 384–395. doi:10.1071/CH06457.

- ↑ Spiteri, Christian; Moses, John E. (2010). "Copper-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition: Regioselective Synthesis of 1,4,5-Trisubstituted 1,2,3-Triazoles". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (1): 31–33. doi:10.1002/anie.200905322.

- ↑ Hoyle, Charles E.; Bowman, Christopher N. (2010). "Thiol–Ene Click Chemistry". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (9): 1540–1573. doi:10.1002/anie.200903924.

- ↑ Lowe, A. B. Polymer Chemistry 2010, 1 (1), 17–36. DOI: 10.1039/B9PY00216B

- ↑ Blackman, Melissa L.; Royzen Maksim; Fox, Joseph M. (2008). "Tetrazine Ligation: Fast Bioconjugation Based on Inverse-Electron-Demand Diels−Alder Reactivity". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (41): 13518–13519. doi:10.1021/ja8053805. PMC 2653060

. PMID 18798613.Devaraj, Neal K.; Weissleder Ralph & Hilderbrand, Scott A. (2008). "Tetrazine Based Cycloadditions: Application to Pretargeted Live Cell Labeling". Bioconjugate Chemistry. 19 (12): 2297–2299. doi:10.1021/bc8004446. PMC 2677645

. PMID 18798613.Devaraj, Neal K.; Weissleder Ralph & Hilderbrand, Scott A. (2008). "Tetrazine Based Cycloadditions: Application to Pretargeted Live Cell Labeling". Bioconjugate Chemistry. 19 (12): 2297–2299. doi:10.1021/bc8004446. PMC 2677645 . PMID 19053305.

. PMID 19053305.

- ↑ Stöckmann, Henning; Neves, Andre; Stairs, Shaun; Brindle, Kevin; Leeper, Finian (2011). "Exploring isonitrile-based click chemistry for ligation with biomolecules". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 9: 7303. doi:10.1039/C1OB06424J.

- ↑ Kashemirov, Boris A.; Bala, Joy L. F.; Chen, Xiaolan; Ebetino, F. H.; Xia, Zhidao; Russell, R. Graham G.; Coxon, Fraser P.; Roelofs, Anke J.; Rogers Michael J.; McKenna, Charles E. (2008). "Fluorescently labeled risedronate and related analogues: "magic linker" synthesis". Bioconjugate Chemistry. 19: 2308–2310. doi:10.1021/bc800369c.

- ↑ Development and Applications of Click Chemistry Gregory C. Patton November 8, 2004 http://www.scs.uiuc.edu Online

- ↑ Kolb, H.C.; Sharpless, B.K. (2003). "The growing impact of click chemistry on drug discovery". Drug Discov Today. 8 (24): 1128–1137. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(03)02933-7. PMID 14678739.

- 1 2 3 L. Liang and D. Astruc: “The copper(I)-catalysed alkyne-azide cycloaddition (CuAAC) “click” reaction and its applications. An overview”, 2011, 255 , 23-24, 2933-2045, p. 2934

- ↑ Rostovtsev, Vsevolod V.; Green, Luke G; Fokin, Valery V.; Sharpless, K. Barry (2002). "A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective "Ligation" of Azides and Terminal Alkynes". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 41 (14): 2596–2599. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::aid-anie2596>3.0.co;2-4.

- ↑ Tornoe, C. W.; Christensen, C.; Meldal, M. (2002). "Peptidotriazoles on Solid Phase: [1,2,3]-Triazoles by Regiospecific Copper(I)-Catalyzed 1,3-Dipolar Cycloadditions of Terminal Alkynes to Azides". Journal of Organic Chemistry. 67 (9): 3057–3064. doi:10.1021/jo011148j. PMID 11975567.

- ↑ K. Wang, X. Bi, S. Xing, P. Liao, Z. Fang, X. Meng, Q. Zhang, Q. Liu, Y. Ji Green Chem., 13 (2011), p. 562

- ↑ B. T. Worrell, J. A. Malik, V. V. Fokin*, 2013, 340, 457-459 ; J.E. Hein, V.V. Fokin, Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2010) 1302.

- ↑ (a) Brotherton, W. S.; Michaels, H. A.; Simmons, J. T.; Clark, R.J.; Dalal, N. S.; Zhu, L. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4954. (b) Kuang, G.-C.; Michaels, H. A.; Simmons, J. T.; Clark, R. J.; Zhu, L. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 6540. (c) Uttamapinant, C.; Tangpeerachaikul, A.; Grecian, S.; Clarke, S.; Singh, U.; Slade, P.; Gee, K. R.; Ting, A. Y. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5852

- ↑ (a) Alder, K.; Stein, G.; Finzenhagen, H. Justus Liebigs Ann.Chem 1931, 485, 211. (b) Alder, K.; Stein, G. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1933, 501, 1. (c) Wittig, G.; Krebs, A. Chem. Ber. 1961, 94, 3260.

- ↑ Boren BC1, Narayan S, Rasmussen LK, Zhang L, Zhao H, Lin Z, Jia G, Fokin VV, J Am Chem Soc. 2008 Jul 16;130(28):8923-30

- ↑ Huisgen, R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1963, 2, 565 , Agard, N. J.; Baskin, J. M.; Prescher, J. A.; Lo, A.; Bertozzi, C. R. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 644.

- ↑ Agard, N. J.; Baskin, J. M.; Prescher, J. A.; Lo, A.; Bertozzi, C. R. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 644.

- ↑ (59) Codelli, J. A.; Baskin, J. M.; Agard, N. J.; Bertozzi, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11486. (60) Ning, X.; Guo, J.; Wolfert, M. A.; Boons, G.-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2253. (61) Gordon, C. G.; Mackey, J. L.; Jewett, J. C.; Sletten, E. M.; Houk, K. N.; Bertozzi, C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9199.

- ↑ MacKenzie DA, Sherratt AR, Chigrinova M, Cheung LL, Pezacki JP. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2014 Aug;21:81-8.

- ↑ (64) (a) Ning, X.; Temming, R. P.; Dommerholt, J.; Guo, J.; Ania, D.B.; Debets, M. F.; Wolfert, M. A.; Boons, G.-J.; van Delft, F. L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3065. (b) McKay, C. S.; Moran, J.; Pezacki, J. P. Chem. Commun. (Cambridge, U. K.) 2010, 46, 931. (c) Debets, M. F.; van Berkel, S. S.; Dommerholt, J.; Dirks, A. T. J.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T.; van Delft, F. L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 805. (d) McKay, C. S.; Chigrinova, M.; Blake, J. A.; Pezacki, J. P. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 3066.

- ↑ Douglas A MacKenzie1,2, Allison R Sherratt1, Mariya Chigrinova1,2, Lawrence LW Cheung1,2 and John Paul Pezacki1,2, 2014, 21:81-88.

- ↑ K. Lang and J. Chin: “Bioorthogonal Reactions for Labeling Proteins.” ACS Chem. Biol., 2014, 9(1), pp 16-20; MacKenzie DA, Pezacki JP: Kinetics studies of rapid strain- promoted [3+2] cycloadditions of nitrones with bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne. Can J Chem 2014, 92:337-340.

- ↑ K. Lang and J. Chin: “Bioorthogonal Reactions for Labeling Proteins.” ACS Chem. Biol., 2014, 9(1), pp 16-20

- ↑ (67) (a) van Berkel, S. S.; Dirks, A. T. J.; Meeuwissen, S. A.; Pingen, D. L. L.; Boerman, O. C.; Laverman, P.; van Delft, F. L.; Cornelissen, J. J. L. M.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. ChemBioChem 2008, 9, 1805. (b) van Berkel, S. S.; Dirks, A. T. J.; Debets, M. F.; van Delft, F. L.; Cornelissen, J. J. L. M.; Nolte, R. J. M.; Rutjes, F. P. J. T. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 150

- 1 2 Houk et al, 2013, 135, 15642-15649

- ↑ Rieder U1, Luedtke NW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014 Aug 25;53(35):9168-72

- ↑ Ramil, C. and Lin, Q. Current opinion in Chemical biology, 2014, 21:89-95.

- ↑ Devaraj, N. K.; Weissleder, R.; Hilderbrand, S. A. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 2297.

- ↑ Ding, H.; Demple, B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 5146.

- ↑ Dieterich et al. Nature Protocols 2, 532 - 540 (2007)

- ↑ Yu et al. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012 Oct 15; 51(42): 10600–10604.

- ↑ (a) Liang, G.; Ren, H.; Rao, J. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 54. (b) Ren,H.; Xiao, F.; Zhan, K.; Kim, Y.-P.; Xie, H.; Xia, Z.; Rao, J. Angew.Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 9658.

- ↑ Ilya A. Osterman; Alexey V. Ustinov; Denis V. Evdokimov; Vladimir A. Korshun; Petr V. Sergiev; Marina V. Serebryakova; Irina A. Demina; Maria A. Galyamina; Vadim M. Govorun; Olga A. Dontsova (January 2013). "A nascent proteome study combining click chemistry with 2DE" (PDF). PROTEOMICS. 13 (1): 17–21. doi:10.1002/pmic.201200393. PMID 23161590.

- ↑ Cox, Courtney L.; Tietz, Jonathan I.; Sokolowski, Karol; Melby, Joel O.; Doroghazi, James R.; Mitchell, Douglas A. (17 June 2014). "Nucleophilic 1,4-Additions for Natural Product Discovery". ACS Chemical Biology. 9: 140806164747005. doi:10.1021/cb500324n.

- ↑ Michael Floros; Alcides Leão; Suresh Narine (2014). "Vegetable Oil Derived Solvent, and Catalyst Free "Click Chemistry" Thermoplastic Polytriazoles". BioMed Research International. 2014: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2014/792901.

- ↑ Gabor London; Kuang-Yen Chen; Gregory T. Carroll; Ben L. Feringa (2013). "Towards Dynamic Control of Wettability by Using Functionalized Altitudinal Molecular Motors on Solid Surfaces". Chemistry: A European Journal. 19 (32): 10690–10697. doi:10.1155/2014/792901.

- ↑ John E. Moses; Adam D. Moorhouse (2007). "The growing applications of click chemistry". Chem. Soc. Rev. 36 (8): 1249–1262. doi:10.1039/b613014n. PMID 17619685.

- ↑ Jean-François Lutz; Zoya Zarafshani (2008). "Efficient construction of therapeutics, bioconjugates, biomaterials and bioactive surfaces using azide–alkyne "click" chemistry". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 60 (9): 958–970. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2008.02.004.

- ↑ http://www.scripps.edu/research/technology/clickchem.html

- ↑ https://ir.lifetechnologies.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=538901

- ↑ http://www.xconomy.com/seattle/2010/07/14/allozyne-licenses-scripps-chemistry/

- ↑ http://www.xconomy.com/boston/2010/11/30/aileron-and-scripps-ink-deal/

- ↑ http://www.integrated-diagnostics.com/press-releases/barry-sharpless-click-chemistry/

- ↑ http://www.basf.com/group/pressrelease/P-10-427

- ↑ http://www.chromeon.com/

External links

- Click Chemistry: Short Review and Recent Literature

- National Science Foundation: Feature "Going Live with Click Chemistry."

- Chemical and Engineering News: Feature "In-Situ Click Chemistry."

- Chemical and Engineering News: Feature "Copper-free Click Chemistry"

- Metal-free click chemistry review

- Click Chemistry - a Chem Soc Rev themed issue highlighting the latest applications of click chemistry, guest edited by M G Finn and Valery Fokin. Published by the Royal Society of Chemistry