Bioinorganic chemistry

Bioinorganic chemistry is a field that examines the role of metals in biology. Bioinorganic chemistry includes the study of both natural phenomena such as the behavior of metalloproteins as well as artificially introduced metals, including those that are non-essential, in medicine and toxicology. Many biological processes such as respiration depend upon molecules that fall within the realm of inorganic chemistry. The discipline also includes the study of inorganic models or mimics that imitate the behaviour of metalloproteins.[1]

As a mix of biochemistry and inorganic chemistry, bioinorganic chemistry is important in elucidating the implications of electron-transfer proteins, substrate bindings and activation, atom and group transfer chemistry as well as metal properties in biological chemistry.

Composition of living organisms

About 99% of mammals' mass are the elements carbon, nitrogen, calcium, sodium, chlorine, potassium, hydrogen, phosphorus, oxygen and sulfur.[2] The organic compounds (proteins, lipids and carbohydrates) contain the majority of the carbon and nitrogen and most of the oxygen and hydrogen is present as water.[2] The entire collection of metal-containing biomolecules in a cell is called the metallome.

History

Paul Ehrlich used organoarsenic (“arsenicals”) for the treatment of syphilis, demonstrating the relevance of metals, or at least metalloids, to medicine, that blossomed with Rosenberg’s discovery of the anti-cancer activity of cisplatin (cis-PtCl2(NH3)2). The first protein ever crystallized (see James B. Sumner) was urease, later shown to contain nickel at its active site. Vitamin B12, the cure for pernicious anemia was shown crystallographically by Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin to consist of a cobalt in a corrin macrocycle. The Watson-Crick structure for DNA demonstrated the key structural role played by phosphate-containing polymers.

Themes in bioinorganic chemistry

Several distinct systems are of identifiable in bioinorganic chemistry. Major areas include:

Metal ion transport and storage

This topic covers a diverse collection of ion channels, ion pumps (e.g. NaKATPase), vacuoles, siderophores, and other proteins and small molecules which control the concentration of metal ions in the cells. One issue is that many metals that are metabolically required are not readily available owing to solubility or scarcity. Organisms have developed a number of strategies for collecting such elements and transporting them.

Enzymology

Many reactions in life sciences involve water and metal ions are often at the catalytic centers (active sites) for these enzymes, i.e. these are metalloproteins. Often the reacting water is a ligand (see metal aquo complex). Examples of hydrolase enzymes are carbonic anhydrase, metallophosphatases, and metalloproteinases. Bioinorganic chemists seek to understand and replicate the functi on of these metalloproteins.

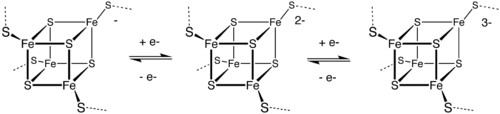

Metal-containing electron transfer proteins are also common. They can be organized into three major classes: iron-sulfur proteins (such as rubredoxins, ferredoxins, and Rieske proteins), blue copper proteins, and cytochromes. These electron transport proteins are complementary to the non-metal electron transporters nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). The nitrogen cycle make extensive use of metals for the redox interconversions.

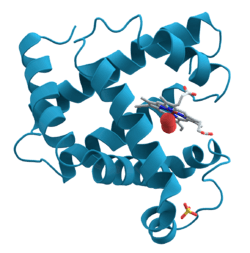

Oxygen transport and activation proteins

Aerobic life make extensive use of metals such as iron, copper, and manganese. Heme is utilized by red blood cells in the form of hemoglobin for oxygen transport and is perhaps the most recognized metal system in biology. Other oxygen transport systems include myoglobin, hemocyanin, and hemerythrin. Oxidases and oxygenases are metal systems found throughout nature that take advantage of oxygen to carry out important reactions such as energy generation in cytochrome c oxidase or small molecule oxidation in cytochrome P450 oxidases or methane monooxygenase. Some metalloproteins are designed to protect a biological system from the potentially harmful effects of oxygen and other reactive oxygen-containing molecules such as hydrogen peroxide. These systems include peroxidases, catalases, and superoxide dismutases. A complementary metalloprotein to those that react with oxygen is the oxygen evolving complex present in plants. This system is part of the complex protein machinery that produces oxygen as plants perform photosynthesis.

Bioorganometallic chemistry

Bioorganometallic systems feature metal-carbon bonds as structural elements or as intermediates. Bioorganometallic enzymes and proteins include the hydrogenases, FeMoco in nitrogenase, and methylcobalamin. These naturally occurring organometallic compounds. This area is more focused on the utilization of metals by unicellular organisms. Bioorganometallic compounds are significant in environmental chemistry.[3]

Metals in medicine

A number of drugs contain metals. This theme relies on the study of the design and mechanism of action of metal-containing pharmaceuticals, and compounds that interact with endogenous metal ions in enzyme active sites. The most widely used anti-cancer drug is cisplatin. MRI contrast agent commonly contain gadolinium. Lithium carbonate has been used to treat the manic phase of bipolar disorder. Gold antiarthritic drugs, e.g. auranofin have been commerciallized. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules are metal complexes have been developed to suppress inflammation by releasing small amounts of carbon monoxide. The cardiovascular and neuronal importance of nitric oxide has been examined, including the enzyme nitric oxide synthase. (See also: nitrogen assimilation.)

Environmental chemistry

Environmental chemistry traditionally emphasizes the interaction of heavy metals with organisms. Methylmercury has caused major disaster called Minamata disease. Arsenic poisoning is a widespread problem owing largely to arsenic contamination of groundwater, which affects many millions of people in developing countries. The metabolism of mercury- and arsenic-containing compounds involves cobalamin-based enzymes.

Biomineralization

Biomineralization is the process by which living organisms produce minerals, often to harden or stiffen existing tissues. Such tissues are called mineralized tissues.[4][5][6] Examples include silicates in algae and diatoms, carbonates in invertebrates, and calcium phosphates and carbonates in vertebrates.Other examples include copper, iron and gold deposits involving bacteria. Biologically-formed minerals often have special uses such as magnetic sensors in magnetotactic bacteria (Fe3O4), gravity sensing devices (CaCO3, CaSO4, BaSO4) and iron storage and mobilization (Fe2O3•H2O in the protein ferritin). Because extracellular[7] iron is strongly involved in inducing calcification,[8][9] its control is essential in developing shells; the protein ferritin plays an important role in controlling the distribution of iron.[10]

Types of inorganic elements in biology

Alkali and alkaline earth metals

The abundant inorganic elements act as ionic electrolytes. The most important ions are sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, phosphate, and the organic ion bicarbonate. The maintenance of precise gradients across cell membranes maintains osmotic pressure and pH.[12] Ions are also critical for nerves and muscles, as action potentials in these tissues are produced by the exchange of electrolytes between the extracellular fluid and the cytosol.[13] Electrolytes enter and leave cells through proteins in the cell membrane called ion channels. For example, muscle contraction depends upon the movement of calcium, sodium and potassium through ion channels in the cell membrane and T-tubules.[14]

Transition metals

The transition metals are usually present as trace elements in organisms, with zinc and iron being most abundant.[15][16][17] These metals are used in some proteins as cofactors and are essential for the activity of enzymes such as catalase and oxygen-carrier proteins such as hemoglobin.[18] These cofactors are bound tightly to a specific protein; although enzyme cofactors can be modified during catalysis, cofactors always return to their original state after catalysis has taken place. The metal micronutrients are taken up into organisms by specific transporters and bound to storage proteins such as ferritin or metallothionein when not being used.[19][20] Cobalt is essential for the functioning of vitamin B12.[21]

Main group compounds

Many other elements aside from metals are bio-active. Sulfur and phosphorus are required for all life. Phosphorus almost exclusively exists as phosphate and its various esters. Sulfur exists in a variety of oxidation states, ranging from sulfate (SO42−) down to sulfide (S2−). Selenium is a trace element involved in proteins that are antioxidants. Cadmium is important because of its toxicity.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ Stephen J. Lippard, Jeremy M. Berg, Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry, University Science Books, 1994, ISBN 0-935702-72-5

- 1 2 Heymsfield S, Waki M, Kehayias J, Lichtman S, Dilmanian F, Kamen Y, Wang J, Pierson R (1991). "Chemical and elemental analysis of humans in vivo using improved body composition models". American Journal of Physiology. 261 (2 Pt 1): E190–8. PMID 1872381.

- ↑ Sigel, A.; Sigel, H.; Sigel, R.K.O., eds. (2010). Organometallics in Environment and Toxicology. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 7. Cambridge: RSC publishing. ISBN 978-1-84755-177-1.

- ↑ Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K.O. Sigel, ed. (2008). Biomineralization: From Nature to Application. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 4. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-03525-2.

- ↑ Weiner, Stephen; Lowenstam, Heinz A. (1989). On biomineralization. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-504977-2.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Cuif; Yannicke Dauphin; James E. Sorauf (2011). Biominerals and fossils through time. Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-87473-1.

- ↑ Gabbiani G, Tuchweber B (1963). "The role of iron in the mechanism of experimental calcification". J Histochem Cytochem. 11 (6): 799–803. doi:10.1177/11.6.799.

- ↑ Schulz, K.; Zondervan, I.; Gerringa, L.; Timmermans, K.; Veldhuis, M.; Riebesell, U. (2004). "Effect of trace metal availability on coccolithophorid calcification.". Nature. 430 (7000): 673–676. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..673S. doi:10.1038/nature02631. PMID 15295599.

- ↑ Anghileri, L. J.; Maincent, P.; Cordova-Martinez, A. (1993). "On the mechanism of soft tissue calcification induced by complexed iron". Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology. 45 (5–6): 365–368. doi:10.1016/S0940-2993(11)80429-X. PMID 8312724.

- ↑ Jackson, D. J.; Wörheide, G.; Degnan, B. M. (2007). "Dynamic expression of ancient and novel molluscan shell genes during ecological transitions". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 160. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-160. PMC 2034539

. PMID 17845714.

. PMID 17845714. - ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-08-037941-9.

- ↑ Sychrová H (2004). "Yeast as a model organism to study transport and homeostasis of alkali metal cations" (PDF). Physiol Res. 53 Suppl 1: S91–8. PMID 15119939.

- ↑ Levitan I (1988). "Modulation of ion channels in neurons and other cells". Annu Rev Neurosci. 11: 119–36. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001003. PMID 2452594.

- ↑ Dulhunty A (2006). "Excitation-contraction coupling from the 1950s into the new millennium". Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 33 (9): 763–72. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04441.x. PMID 16922804.

- ↑ Dlouhy, Adrienne C.; Outten, Caryn E. (2013). "Chapter 8 The Iron Metallome in Eukaryotic Organisms". In Banci, Lucia (Ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-1_8. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- ↑ Mahan D, Shields R (1998). "Macro- and micromineral composition of pigs from birth to 145 kilograms of body weight". J Anim Sci. 76 (2): 506–12. PMID 9498359. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30.

- ↑ Husted S, Mikkelsen B, Jensen J, Nielsen N (2004). "Elemental fingerprint analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare) using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, isotope-ratio mass spectrometry, and multivariate statistics". Anal Bioanal Chem. 378 (1): 171–82. doi:10.1007/s00216-003-2219-0. PMID 14551660.

- ↑ Finney L, O'Halloran T (2003). "Transition metal speciation in the cell: insights from the chemistry of metal ion receptors". Science. 300 (5621): 931–6. Bibcode:2003Sci...300..931F. doi:10.1126/science.1085049. PMID 12738850.

- ↑ Cousins R, Liuzzi J, Lichten L (2006). "Mammalian zinc transport, trafficking, and signals". J Biol Chem. 281 (34): 24085–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.R600011200. PMID 16793761.

- ↑ Dunn L, Rahmanto Y, Richardson D (2007). "Iron uptake and metabolism in the new millennium". Trends Cell Biol. 17 (2): 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.003. PMID 17194590.

- ↑ Cracan, Valentin; Banerjee, Ruma (2013). "Chapter 10 Cobalt and Corrinoid Transport and Biochemistry". In Banci, Lucia (Ed.). Metallomics and the Cell. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 12. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5561-10_10. ISBN 978-94-007-5560-4. electronic-book ISBN 978-94-007-5561-1 ISSN 1559-0836 electronic-ISSN 1868-0402

- ↑ Maret, Wolfgang; Moulis, Jean-Marc (2013). "Chapter 1. The Bioinorganic Chemistry of Cadmium in the Context of its Toxicity". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel. Cadmium: From Toxicology to Essentiality. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 11. Springer. pp. 1–30.

Literature

- Heinz-Bernhard Kraatz (editor), Nils Metzler-Nolte (editor), Concepts and Models in Bioinorganic Chemistry, John Wiley and Sons, 2006, ISBN 3-527-31305-2

- Ivano Bertini, Harry B. Gray, Edward I. Stiefel, Joan Selverstone Valentine, Biological Inorganic Chemistry, University Science Books, 2007, ISBN 1-891389-43-2

- Wolfgang Kaim, Brigitte Schwederski "Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic Elements in the Chemistry of Life." John Wiley and Sons, 1994, ISBN 0-471-94369-X

- Rosette M. Roat-Malone, Bioinorganic Chemistry : A Short Course, Wiley-Interscience, 2002, ISBN 0-471-15976-X

- J.J.R. Fraústo da Silva and R.J.P. Williams, The biological chemistry of the elements: The inorganic chemistry of life, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-850848-4

- Lawrence Que, Jr., ed., Physical Methods in Bioinorganic Chemistry, University Science Books, 2000, ISBN 1-891389-02-5

External links

- The Society of Biological Inorganic Chemistry (SBIC)'s home page

- The French Bioinorganic Chemistry Society

- Metal Ions in Life Sciences

- Glossary of Terms in Bioinorganic Chemistry

- Metal Coordination Groups in Proteins by Marjorie Harding

- European Bioinformatics Institute

- MetalPDB: A database of metal sites in biomolecular structures