Clove

| Clove | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Myrtales |

| Family: | Myrtaceae |

| Genus: | Syzygium |

| Species: | S. aromaticum |

| Binomial name | |

| Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merrill & Perry | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Cloves are the aromatic flower buds of a tree in the family Myrtaceae, Syzygium aromaticum. They are native to the Maluku Islands in Indonesia, and are commonly used as a spice. Cloves are commercially harvested primarily in Bangladesh, Indonesia, India, Madagascar, Zanzibar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania. Cloves are available throughout the year.

Botanical features

The clove tree is an evergreen that grows up to 8–12 m tall, with large leaves and sanguine flowers grouped in terminal clusters. The flower buds initially have a pale hue, gradually turn green, then transition to a bright red when ready for harvest. Cloves are harvested at 1.5–2.0 cm long, and consist of a long calyx that terminates in four spreading sepals, and four unopened petals that form a small central ball.

Uses

Cloves are used in the cuisine of Asian, African, and the Near and Middle East countries, lending flavor to meats, curries, and marinades, as well as fruit such as apples, pears or rhubarb. Cloves may be used to give aromatic and flavor qualities to hot beverages, often combined with other ingredients such as lemon and sugar. They are a common element in spice blends such as pumpkin pie spice and speculoos spices.

In Mexican cuisine, cloves are best known as clavos de olor, and often accompany cumin and cinnamon.[2] They are also used in Peruvian cuisine, in a wide variety of dishes as carapulcra and arroz con leche.

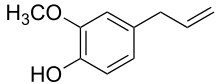

A major component of clove taste is imparted by the chemical eugenol,[3] and the quantity of the spice required is typically small. It pairs well with cinnamon, allspice, vanilla, red wine and basil, as well as onion, citrus peel, star anise, or peppercorns.

Non-culinary uses

The spice is used in a type of cigarette called kretek in Indonesia.[1] Clove cigarettes have been smoked throughout Europe, Asia and the United States. Starting in 2009, clove cigarettes must be classified as cigars in the US.[4]

Because of the bioactive chemicals of clove, the spice may be used as an ant repellent.[5]

Cloves can be used to make a fragrance pomander when combined with an orange. When given as a gift in Victorian England, such a pomander indicated warmth of feeling.

Traditional medicinal uses

Cloves are used in Indian Ayurvedic medicine, Chinese medicine, and western herbalism and dentistry where the essential oil is used as an anodyne (painkiller) for dental emergencies. Cloves are used as a carminative, to increase hydrochloric acid in the stomach and to improve peristalsis. Cloves are also said to be a natural anthelmintic.[6] The essential oil is used in aromatherapy when stimulation and warming are needed, especially for digestive problems. Topical application over the stomach or abdomen are said to warm the digestive tract. Applied to a cavity in a decayed tooth, it also relieves toothache.[7]

In Chinese medicine, cloves or ding xiang are considered acrid, warm, and aromatic, entering the kidney, spleen and stomach meridians, and are notable in their ability to warm the middle, direct stomach qi downward, to treat hiccup and to fortify the kidney yang.[8] Because the herb is so warming, it is contraindicated in any persons with fire symptoms and according to classical sources should not be used for anything except cold from yang deficiency. As such, it is used in formulas for impotence or clear vaginal discharge from yang deficiency, for morning sickness together with ginseng and patchouli, or for vomiting and diarrhea due to spleen and stomach coldness.[8]

Cloves may be used internally as a tea and topically as an oil for hypotonic muscles, including for multiple sclerosis. This is also found in Tibetan medicine.[9] Some recommend avoiding more than occasional use of cloves internally in the presence of pitta inflammation such as is found in acute flares of autoimmune diseases.[10]

Potential medicinal uses

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has reclassified eugenol (one of the chemicals contained in clove oil), downgrading its effectiveness rating. The FDA now believes not enough evidence indicates clove oil or eugenol is effective for toothache pain or a variety of other types of pain.[11]

Studies to determine its effectiveness for fever reduction, as a mosquito repellent, and to prevent premature ejaculation have been inconclusive.[11] It remains unproven whether clove may reduce blood sugar levels.[12]

In addition, clove oil is used in preparation of some toothpastes and Clovacaine solution, which is a local anesthetic used in oral ulceration and inflammation. Eugenol (or clove oil generally) is mixed with zinc oxide to form a temporary tooth cavity filling.[13]

Clove oil can be used to anesthetize fish, and prolonged exposure to higher doses (the recommended dose is 400 mg/l) is considered a humane means of euthanasia.[14]

Adulteration

Clove stalks are slender stems of the inflorescence axis that show opposite decussate branching. Externally, they are brownish, rough, and irregularly wrinkled longitudinally with short fracture and dry, woody texture.

Mother cloves (anthophylli) are the ripe fruits of cloves that are ovoid, brown berries, unilocular and one-seeded. This can be detected by the presence of much starch in the seeds.

Brown cloves are expanded flowers from which both corollae and stamens have been detached.

Exhausted cloves have most or all the oil removed by distillation. They yield no oil and are darker in color.[15]

History

Archeologists have found cloves in a ceramic vessel in Syria, with evidence that dates the find to within a few years of 1721 BC.[16] In the third century BC, a Chinese leader in the Han Dynasty required those who addressed him to chew cloves to freshen their breath.[17] Cloves were traded by Muslim sailors and merchants during the Middle Ages in the profitable Indian Ocean trade, the clove trade is also mentioned by Ibn Battuta and even famous Arabian Nights characters such as Sinbad the Sailor are known to have bought and sold cloves from India.[18]

Until modern times, cloves grew only on a few islands in the Moluccas (historically called the Spice Islands), including Bacan, Makian, Moti, Ternate, and Tidore.[16] In fact, the clove tree that experts believe is the oldest in the world, named Afo, is on Ternate. The tree is between 350 and 400 years old.[19] Tourists are told that seedlings from this very tree were stolen by a Frenchman named Poivre in 1770, transferred to France, and then later to Zanzibar, which was once the world's largest producer of cloves.[19]

Until cloves were grown outside of the Maluku Islands, they were traded like oil, with an enforced limit on exportation.[19] As the Dutch East India Company consolidated its control of the spice trade in the 17th century, they sought to gain a monopoly in cloves as they had in nutmeg. However, "unlike nutmeg and mace, which were limited to the minute Bandas, clove trees grew all over the Moluccas, and the trade in cloves was way beyond the limited policing powers of the corporation."[20]

Chemical compounds

Eugenol comprises 72–90% of the essential oil extracted from cloves and is the compound most responsible for clove aroma.[3] Other important essential oil constituents of clove oil include acetyl eugenol, beta-caryophyllene and vanillin, crategolic acid, tannins such as bicornin,[3][21] gallotannic acid, methyl salicylate (painkiller), the flavonoids eugenin, kaempferol, rhamnetin, and eugenitin, triterpenoids such as oleanolic acid, stigmasterol, and campesterol and several sesquiterpenes.[22]

Eugenol is toxic in relatively small quantities; for example, a dose of 5–10 ml has been reported as a near fatal dose for a two-year-old child.[23]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clove. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Cloves. |

References

- 1 2 "Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. & L. M. Perry". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ↑ Dorenburg, Andrew and Page, Karen. The New American Chef: Cooking with the Best Flavors and Techniques from Around the World, John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2003

- 1 2 3 Kamatou GP1, Vermaak I, Viljoen AM (2012). "Eugenol--from the remote Maluku Islands to the international market place: a review of a remarkable and versatile molecule". Molecules. 17 (6): 6953–81. doi:10.3390/molecules17066953.

- ↑ "Flavored Tobacco". FDA.gov. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Get Rid of Ants 24". getridofanst24.

- ↑ Balch, Phyllis and Balch, James. Prescription for Nutritional Healing, 3rd ed., Avery Publishing, 2000, p. 94

- ↑ Alqareer A, Alyahya A, Andersson L (May 24, 2012). "The effect of clove and benzocaine versus placebo as topical anesthetics". Journal of dentistry. 34 (10): 747–50. doi:10.1016/j.jdent.2006.01.009. PMID 16530911.

- 1 2 Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, and Andrew Gamble 2004

- ↑ "Question: Multiple Sclerosis". TibetMed. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ Tillotson, Alan (April 3, 2005). "Special Diets for Illness". Oneearthherbs.squarespace.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- 1 2 "Clove". MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine and National Institutes of Health. 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Clove (Eugenia aromatica) and Clove oil (Eugenol)". National Institutes of Health, Medicine Plus. nlm.nih.gov. February 15, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- ↑ Youngken, H.W. (1950). Text book of pharmacognosy (6th ed.).

- ↑ Monks, Neale. "Aquarium Fish Euthanasia: Euthanizing and disposing of aquarium fish.". FishChannel.com. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ↑ Bisset, N.G. (1994). Herbal drugs and phyotpharmaceuticals, Medpharm. Stuttgart: Scientific Publishers.

- 1 2 Turner, Jack (2004). Spice: The History of a Temptation. Vintage Books. pp. xxvii–xxviii. ISBN 0-375-70705-0.

- ↑ Andaya, Leonard Y. (1993). "1: Cultural State Formation in Eastern Indonesia". In Reid, Anthony. Southeast Asia in the early modern era: trade, power, and belief. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8093-5.

- ↑ "The Third Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman - The Arabian Nights - The Thousand and One Nights - Sir Richard Burton translator". Classiclit.about.com. April 10, 2012. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Worrall, Simon (June 23, 2012). "The world's oldest clove tree". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ↑ Krondl, Michael. The Taste of Conquest: The Rise and Fall of the Three Great Cities of Spice. New York: Ballantine Books, 2007.

- ↑ Li-Ming Bao, Eerdunbayaer; Akiko Nozaki; Eizo Takahashi; Keinosuke Okamoto; Hideyuki Ito & Tsutomu Hatano (2012). "Hydrolysable Tannins Isolated from Syzygium aromaticum: Structure of a New C-Glucosidic Ellagitannin and Spectral Features of Tannins with a Tergalloyl Group.". Heterocycles. 85 (2): 365–81. doi:10.3987/COM-11-12392.

- ↑ Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, and Andrew Gamble. 2004

- ↑ Hartnoll, G; Moore, D; Douek, D (1993). "Near fatal ingestion of oil of cloves". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 69 (3): 392–3. doi:10.1136/adc.69.3.392. PMC 1029532

. PMID 8215554.

. PMID 8215554.

Further reading

Liu, Bin-Bin; Liu, Luo; Liu, Xiao-Long; Geng, Di; Li, Cheng-Fu; Chen, Shao-Mei; Chen, Xue-Mei; Yi, Li-Tao; Liu, Qing (February 2015). "Essential Oil of Syzygium aromaticum Reverses the Deficits of Stress-Induced Behaviors and Hippocampal p-ERK/p-CREB/Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression". Planta Medica. 81 (3): 185–192. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1396150. Retrieved 27 April 2015.