Communist state

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

|

|

Concepts

|

|

Internationals |

|

Related topics |

|

|

| History of communist states |

|---|

| Current communist states |

|

Non-communist states with communist majority |

| Previous communist states |

|

| Post-Soviet states |

| Communism portal |

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||||

| Basic forms of government | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power structure | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power source | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Power ideology | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Politics portal | ||||||||

A communist state is a state that is usually administered and governed by a single party representing the proletariat, guided by Marxist-Leninist philosophy, with the aim of achieving communism. There have been several instances of Communist states with functioning political participation processes involving several other non-Party organisations, such as trade unions, factory committees, and direct democratic participation.[1][2][3][4][5] The term "Communist state" is used by Western historians, political scientists and media to refer to these countries. However, contrary to Western usage, these states do not describe themselves as "communist" nor do they claim to have achieved communism; they refer to themselves as Socialist states or Workers' states that are in the process of constructing socialism.[6][7][8][9]

Communist states can be administered by a single, centralised party apparatus, although countries such as the DPRK have several parties. These parties usually are Marxism–Leninist or some variation thereof (including Maoism in China and Juche in North Korea), with the official aim of achieving socialism and progressing toward communism. These states are usually termed by Marxists as dictatorships of the proletariat, or dictatorships of the working class, whereby the working class is the ruling class of the country, in contrast to capitalism, whereby the bourgeoisie is the ruling class.

Communist states such as the USSR and the PRC were criticized by Western authors and organisations on the basis of a lack of multi-party Western democracy,[10][11] in addition to several other areas where socialist society and Western societies differed. This state structure was derived in part from the Leninist concept of democratic centralism,[12] although the USSR permitted nomination of candidates to soviets by trade unions, religious organisations, factory committees, as well as the Communist Party itself[13] after the several democratic amendments made to the 1936 Soviet Constitution.[14] For instance, criticisms were commonly levied upon the structure of socialised ownership in Communist countries, contrasting private ownership of the means of production to common ownership through co-operatives and state administration.[15] Communist states have also been criticised for the influence and outreach of their respective ruling parties on society, in addition to lack of recognition for some Western legal rights and liberties [16] such as the right to ownership of private property, and the restriction of the right to free speech. Soviet advocates and socialists responded to these criticisms by highlighting the ideological differences in the concept of "freedom". McFarland and Ageyev noted that "Marxist-Leninist norms disparaged laissez-faire individualism (as when housing is determined by one's ability to pay), also [condemning] wide variations in personal wealth as the West has not. Instead, Soviet ideals emphasized equality—free education and medical care, little disparity in housing or salaries, and so forth."[17] When asked to comment on the claim that former citizens of Communist states enjoy increased freedoms, Heinz Kessler, former East German defense minister replied that “Millions of people in Eastern Europe are now free from employment, free from safe streets, free from health care, free from social security.”[18] The early economic development policies of Communist states have been criticised for focusing primarily on the development of heavy industry.

Communist party as the leader of the state

In the theories of German philosopher Karl Marx, a state in any society is an instrument of oppression by one social class over another, historically a minority exploiter class ruling over a majority exploited class. Marx saw that in his contemporary time, the new nation states were characterized by increasingly intensified class contradiction between the capitalist class and the working class it ruled over. He predicted that if the class contradictions of the capitalist system continue to intensify, that the working class will ultimately become conscious of itself as an exploited collective and will overthrow the capitalists and establish collective ownership over the means of production, therein arriving at a new phase of development called Socialism (in Marxist understanding). The state ruled by the working class during the transition into classless society is called the "dictatorship of the proletariat". Vladimir Lenin created revolutionary vanguard theory in an attempt to expand on the concept. Lenin saw that science is something that is initially practicable by only a minority of society who happen to be in a position free from distraction so that they may contemplate it, and believed that scientific socialism was no exception. He therefore advocated that the Communist party should be structured as a vanguard of those who have achieved full class consciousness to be at the forefront of the class struggle and lead the workers to expand class consciousness and replace the capitalist class as the ruling class, therein establishing the Proletarian state.

Development of Communist states

During the 20th century, the world's first constitutionally socialist state was in Russia in 1917. In 1922, it joined other former territories of the empire to become the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). After World War II, the Soviet Army occupied much of Eastern Europe and thus helped establish Communist states in these countries. Most Communist states in Eastern Europe were allied with the USSR, except for Yugoslavia which declared itself non-aligned. In 1949, after a war against Japanese occupation and a civil war resulting in a Communist victory, the People's Republic of China was established. Communist states were also established in Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. A Communist state was established in North Korea, although it later withdrew from the Communist movement. In 1989, the Communist states in Eastern Europe collapsed under public pressure during a wave of non-violent movements which led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. Today, the existing Communist states in the world are in China, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam.

These Communist states often do not claim to have achieved socialism or communism in their countries; rather, they claim to be building and working toward the establishment of socialism in their countries. For example, the preamble to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam's constitution states that Vietnam only entered a transition stage between capitalism and socialism after the country was re-unified under the Communist party in 1976,[19] and the 1992 constitution of the Republic of Cuba states that the role of the Communist Party is to "guide the common effort toward the goals and construction of socialism".[20]

State institutions in Communist states

Communist states share similar institutions, which are organized on the premise that the Communist party is a vanguard of the proletariat and represents the long-term interests of the people. The doctrine of democratic centralism, which was developed by Vladimir Lenin as a set of principles to be used in the internal affairs of the communist party, is extended to society at large.[21]

According to democratic centralism, all leaders must be elected by the people and all proposals must be debated openly, but, once a decision has been reached, all people have a duty to obey that decision and all debate should end. When used within a political party, democratic centralism is meant to prevent factionalism and splits. When applied to an entire state, democratic centralism creates a one-party system.[21]

The constitutions of most socialist states describe their political system as a form of democracy.[22] Thus, they recognize the sovereignty of the people as embodied in a series of representative parliamentary institutions. Such states do not have a separation of powers; instead, they have one national legislative body (such as the Supreme Soviet in the Soviet Union) which is considered the highest organ of state power and which is legally superior to the executive and judicial branches of government.[23]

Such national legislative politics in socialist states often have a similar structure to the parliaments that exist in liberal republics, with two significant differences: first, the deputies elected to these national legislative bodies are not expected to represent the interests of any particular constituency, but the long-term interests of the people as a whole; second, against Marx's advice, the legislative bodies of socialist states are not in permanent session. Rather, they convene once or several times per year in sessions which usually last only a few days.[24]

When the national legislative body is not in session, its powers are transferred to a smaller council (often called a presidium) which combines legislative and executive power, and, in some socialist states (such as the Soviet Union before 1990), acts as a collective head of state. In some systems, the presidium is composed of important communist party members who vote the resolutions of the communist party into law.

State social institutions

A feature of socialist states is the existence of numerous state-sponsored social organizations (trade unions, youth organizations, women's organizations, associations of teachers, writers, journalists and other professionals, consumer cooperatives, sports clubs, etc.) which are integrated into the political system.

In some socialist states, representatives of these organizations are guaranteed a certain number of seats on the national legislative bodies. In socialist states, the social organizations are expected to promote social unity and cohesion, to serve as a link between the government and society, and to provide a forum for recruitment of new communist party members.[25]

Political power

Historically, the political organization of many socialist states has been dominated by a one-party monopoly. Some Communist governments, such as North Korea, East Germany or Czechoslovakia have or had more than one political party, but all minor parties are or were required to follow the leadership of the Communist party. In socialist states, the government may not tolerate criticism of policies that have already been implemented in the past or are being implemented in the present.[26]

Nevertheless, Communist parties have won elections and governed in the context of multi-party democracies, without seeking to establish a one-party state. Examples include San Marino, Nicaragua (1979-1990),[27] Moldova, Nepal (presently), Cyprus,[28] and the Indian states of Kerala, West Bengal and Tripura.[29] However, for the purposes of this article, these entities do not fall under the definition of socialist state.

Criticism

Countries such as the USSR and the PRC were criticized by Western authors and organisations on the basis of a lack of multi-party Western democracy,[10][11] in addition to several other areas where socialist society and Western societies differed. For instance, socialist societies were commonly characterised by state ownership or social ownership of the means of production either through administration through party organisations, democratically-elected councils and communes and co-operative structures - in opposition to the liberal democratic capitalist free-market paradigm of management, ownership, and control by corporations and private individuals.[15] Communist states have also been criticised for the influence and outreach of their respective ruling parties on society, in addition to lack of recognition for some Western legal rights and liberties [16] such as the right to ownership of private property, and the restriction of the right to free speech.

Soviet advocates and socialists responded to these criticisms by highlighting the ideological differences in the concept of "freedom". McFarland and Ageyev noted that "Marxist-Leninist norms disparaged laissez-faire individualism (as when housing is determined by one's ability to pay), also [condemning] wide variations in personal wealth as the West has not. Instead, Soviet ideals emphasized equality—free education and medical care, little disparity in housing or salaries, and so forth."[17] When asked to comment on the claim that former citizens of Communist states enjoy increased freedoms, Heinz Kessler, former East German defense minister replied that “Millions of people in Eastern Europe are now free from employment, free from safe streets, free from health care, free from social security.”[18] The early economic development policies of Communist states have been criticised for focusing primarily on the development of heavy industry.

In his critique of states run under Marxist–Leninist ideology, economist Michael Ellman of the University of Amsterdam notes that such states compared favorably with Western states in some health indicators such as infant mortality and life expectancy.[30] Similarly, Amartya Sen's own analysis of international comparisons of life expectancy found that several Marxist–Leninist states made significant gains, and commented "one thought that is bound to occur is that communism is good for poverty removal."[31] The dissolution of the Soviet Union was followed by a rapid increase in poverty,[32][33][34] crime,[35][36] corruption,[37][38] unemployment,[39] homelessness,[40][41] rates of disease,[42][43][44] and income inequality,[45] along with decreases in calorie intake, life expectancy, adult literacy, and income.[46]

Modern period

List of current states described as communist

The following countries are one-party states in which the institutions of the ruling communist party and the state have become intertwined. They are generally adherents of Marxism–Leninism in particular. They are listed here together with the year of their founding and their respective ruling parties:[47]

Marxist-Leninist

| Country | Local name | Since | Ruling party |

|---|---|---|---|

| |

In Chinese; Zhōnghuá Rénmín Gònghéguó | 1 October 1949 | Communist Party of China |

| |

In Spanish; República de Cuba | 1 July 1961 | Communist Party of Cuba |

| |

In Lao; Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao | 2 December 1975 | Lao People's Revolutionary Party |

| |

In Vietnamese; Cộng hòa xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam | 2 September 1945 (in the north) 30 April 1975 (in the south) |

Communist Party of Vietnam |

Non-Marxist-Leninist

| Country | Local name | Since | Ruling party | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Korean; Chosŏn minjujuŭi inmin konghwaguk | 9 September 1948 | Workers' Party of Korea | Socialist state although the government's official ideology is now the Juche policy of Kim Il-sung, as opposed to traditional Marxism–Leninism. In 2009, the constitution of the DPRK was quietly amended so that not only did it disavow all Marxist–Leninist references present in the first draft, but it also dropped all reference to 'Communism'.[48] |

Multi-party states with governing communist parties

There are multi-party states with Communist parties leading the government. Such states are not considered to be Communist states as the countries themselves allow for multiple parties, and do not provide a constitutional role for their communist parties.

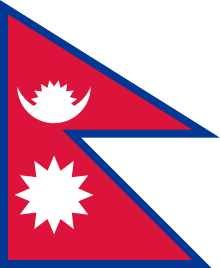

Nepal The Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) is the leading party in the government coalition.

Nepal The Communist Party of Nepal (Unified Marxist–Leninist) is the leading party in the government coalition.

Cyprus, Moldova and Guyana have also recently had officially Marxist–Leninist ruling parties.

See also

- Capitalist state

- Communist society

- Criticisms of communist party rule

- List of anti-capitalist and communist parties with national parliamentary representation

- List of communist parties

- List of socialist states, which includes a list of current and former socialist states.

- People's democracy (Marxism–Leninism)

- Socialist state

- Socialism in One Country

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Communist countries. |

- ↑ Sloan, Pat (1937). "Soviet democracy".

- ↑ Farber, Samuel (1992). "Before Stalinism: The Rise and Fall of Soviet Democracy".

- ↑ Getzler, Israel (2002). "Kronstadt 1917-1921: the fate of a Soviet democracy.". Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Webb, Sidney, and Beatrice Webb (1935). "Soviet communism: a new civilisation?".

- ↑ Busky, Donald F. (July 20, 2000). Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey. Praeger. p. 9. ISBN 978-0275968861.

In a modern sense of the word, communism refers to the ideology of Marxism-Leninism.

- ↑ Wilczynski, J. (2008). The Economics of Socialism after World War Two: 1945-1990. Aldine Transaction. p. 21. ISBN 978-0202362281.

Contrary to Western usage, these countries describe themselves as ‘Socialist’ (not ‘Communist’). The second stage (Marx’s ‘higher phase’), or ‘Communism’ is to be marked by an age of plenty, distribution according to needs (not work), the absence of money and the market mechanism, the disappearance of the last vestiges of capitalism and the ultimate ‘whithering away of the state.

- ↑ Steele, David Ramsay (September 1999). From Marx to Mises: Post Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation. Open Court. p. 45. ISBN 978-0875484495.

Among Western journalists the term ‘Communist’ came to refer exclusively to regimes and movements associated with the Communist International and its offspring: regimes which insisted that they were not communist but socialist, and movements which were barely communist in any sense at all.

- ↑ Rosser, Mariana V. and J Barkley Jr. (July 23, 2003). Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy. MIT Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0262182348.

Ironically, the ideological father of communism, Karl Marx, claimed that communism entailed the withering away of the state. The dictatorship of the proletariat was to be a strictly temporary phenomenon. Well aware of this, the Soviet Communists never claimed to have achieved communism, always labeling their own system socialist rather than communist and viewing their system as in transition to communism.

- ↑ Williams, Raymond (1983). "Socialism". Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society, revised edition. Oxford University Press. p. 289. ISBN 0-19-520469-7.

The decisive distinction between socialist and communist, as in one sense these terms are now ordinarily used, came with the renaming, in 1918, of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) as the All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). From that time on, a distinction of socialist from communist, often with supporting definitions such as social democrat or democratic socialist, became widely current, although it is significant that all communist parties, in line with earlier usage, continued to describe themselves as socialist and dedicated to socialism.

- 1 2 SP, Huntington (1970). Authoritarian politics in modern society: the dynamics of established one-party systems. Basic Books (AZ).

- 1 2 Lowy, Michael (1986). "Mass organization, party, and state: Democracy in the transition to socialism". Transition and Development: Problems of Third World Socialism (94): 264.

- ↑ Waller, Michael (1981). Democratic centralism: an historical commentary. Manchester University Press.

- ↑ Zaslavsky, Victor, and Robert J. Brym (1978). The Functions of Elections in the USSR. Europe‐Asia Studies.

- ↑ Hazard, John (1936). Soviet Law: An Introduction. Columbia Law Review.

- 1 2 Amandae, Sonja (2003). Rationalizing capitalist democracy: The cold war origins of rational choice liberalism. University of Chicago Press.

- 1 2 "Assemblée parlementaire du Conseil de l'Europe". coe.int.

- 1 2 McFarland, Sam; Ageyev, Vladimir; Abalakina-Paap., Marina (1992). "Authoritarianism in the former Soviet Union". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- 1 2 Parenti, Michael (1997). Blackshirts and reds : rational fascism and the overthrow of communism. San Francisco: City Lights Books. p. 118. ISBN 0-87286-330-1.

- ↑ VN Embassy - Constitution of 1992 Archived 9 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Full Text. From the Preamble: "On 2 July 1976, the National Assembly of reunified Vietnam decided to change the country's name to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam; the country entered a period of transition to socialism, strove for national construction, and unyieldingly defended its frontiers while fulfilling its internationalist duty."

- ↑ Cubanet - Constitution of the Republic of Cuba, 1992 Full Text. From Article 5: "The Communist Party of Cuba, a follower of Martí’s ideas and of Marxism-Leninism, and the organized vanguard of the Cuban nation, is the highest leading force of society and of the state, which organizes and guides the common effort toward the goals of the construction of socialism and the progress toward a communist society,"

- 1 2 Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1986, pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1986, p. 12.

- ↑ Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1987, p. 13.

- ↑ Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1986, p. 14.

- ↑ Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1986, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Furtak, Robert K. The political systems of the socialist states, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1986, p. 18-19.

- ↑ Kinzer, Stephen (15 January 1987). "NICARAGUA'S COMMUNIST PARTY SHIFTS TO OPPOSITION". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Cyprus elects its first communist president", The Guardian, 25 February 2008.

- ↑ Kerala Assembly Elections-- 2006

- ↑ Michael Ellman. Socialist Planning. Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 1107427320 p. 372.

- ↑ Richard G. Wilkinson. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge, November 1996. ISBN 0415092353. p. 122

- ↑ McAaley, Alastair. Russia and the Baltics: Poverty and Poverty Research in a Changing World. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ "An epidemic of street kids overwhelms Russian cities". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Targ, Harry (2006). Challenging Late Capitalism, Neoliberal Globalization, & Militarism.

- ↑ Theodore P. Gerber & Michael Hout, "More Shock than Therapy: Market Transition, Employment, and Income in Russia, 1991–1995", AJS Volume 104 Number 1 (July 1998): 1–50.

- ↑ Volkov, Vladimir. "The bitter legacy of Boris Yeltsin (1931-2007)".

- ↑ "Cops for hire". Economist. 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2014". Transparency International. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Hardt, John (2003). Russia's Uncertain Economic Future: With a Comprehensive Subject Index. M. E Sharpe. p. 481.

- ↑ Alexander, Catharine; Buchil, Victor; Humphrey, Caroline (12 September 2007). Urban Life in Post-Soviet Asia. CRC Press.

- ↑ Smorodinskaya. Encyclopaedia of Contemporary Russian. Routledge.

- ↑ Galazkaa, Artur. "Implications of the Diphtheria Epidemic in the Former Soviet Union for Immunization Programs". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 181: 244–248. doi:10.1086/315570.

- ↑ Shubnikov, Eugene. "Non-communicable Diseases and Former Soviet Union countries". Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Wharton, Melinda; Vitek, Charles. "Diphtheria in the Former Soviet Union: Reemergence of a Pandemic Disease". CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Hoepller, C (2011). Russian Demographics: The Role of the Collapse of the Soviet Union.

- ↑ Poland, Marshall. "Russian Economy in the Aftermath of the Collapse of the Soviet Union". Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook: FIELD LISTING :: GOVERNMENT TYPE

- ↑ "DPRK has quietly amended its Constitution". Leonid Petrov's KOREA VISION.