Power and control in abusive relationships

Power and control in abusive relationships (or coercive control or controlling behaviour) is the way that abusers exert physical, sexual and other forms of abuse to gain and maintain control over a victim. Controlling abusers use multiple tactics to exert power and control over their partners. The goal of the abuser is to control and intimidate the victim or to influence them to feel that they do not have an equal voice in the relationship."[1] Manipulators and abusers control their victims with a range of tactics, including positive reinforcement such as praise, negative reinforcement, intermittent or partial reinforcement, psychological punishment (e.g., nagging, silent treatment, swearing, guilt trips) and traumatic tactics such as verbal abuse or explosive anger.[2] Traumatic bonding can occur between the abuser and victim as the result of ongoing cycles of abuse in which the intermittent reinforcement of reward and punishment creates powerful emotional bonds that are resistant to change.[3]

Control freaks

In psychology-related slang, "control freak" is a derogatory term for a person who attempts to dictate how everything around them is done.[4] Control freaks are often perfectionists[5] defending themselves against their own inner vulnerabilities in the belief that if they are not in total control they risk exposing themselves once more to childhood angst.[6] Such persons manipulate and pressure others to change so as to avoid having to change themselves,[7] and use power over others to escape an inner emptiness.[8] In terms of personality-type theory, control freaks are very much the Type A personality, driven by the need to dominate and control.[9] An obsessive need to control others is also associated with antisocial personality disorder.[10]

Psychological manipulation

Braiker identified the following ways that manipulators control their victims:[2]

- Positive reinforcement: includes praise, superficial charm, superficial sympathy (crocodile tears), excessive apologizing, money, approval, gifts, attention, facial expressions such as a forced laugh or smile, and public recognition.

- Negative reinforcement: involves removing one from a negative situation as a reward, e.g. "You won't have to do your homework if you allow me to do this to you."

- Intermittent or partial reinforcement: Partial or intermittent negative reinforcement can create an effective climate of fear and doubt. Partial or intermittent positive reinforcement can encourage the victim to persist.

- Punishment: includes nagging, yelling, the silent treatment, intimidation, threats, swearing, emotional blackmail, the guilt trip, sulking, crying, and playing the victim.

- Traumatic one-trial learning: using verbal abuse, explosive anger, or other intimidating behavior to establish dominance or superiority; even one incident of such behavior can condition or train victims to avoid upsetting, confronting or contradicting the manipulator.

Emotional blackmail

Emotional blackmail is a term coined by psychotherapist Susan Forward, about controlling people in relationships and the theory that fear, obligation and guilt (FOG) are the transactional dynamics at play between the controller and the person being controlled. Understanding these dynamics are useful to anyone trying to extricate from the controlling behavior of another person, and deal with their own compulsions to do things that are uncomfortable, undesirable, burdensome, or self-sacrificing for others.[11]

Forward and Frazier identify four blackmail types each with their own mental manipulation style:[12]

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Punisher's threat | Eat the food I cooked for you or I'll hurt you. |

| Self-punisher's threat | Eat the food I cooked for you or I'll hurt myself. |

| Sufferer's threat | Eat the food I cooked for you. I was saving it for myself. I wonder what will happen now? |

| Tantalizer's threat | Eat the food I cooked for you and you just may get a really yummy dessert. |

There are different levels of demands - demands that are of little consequence, demands that involve important issues or personal integrity, demands that affect major life decisions, and/or demands that are dangerous or illegal.[11]

Silent treatment

The silent treatment is sometimes used as a control mechanism. When so used, it constitutes a passive-aggressive action characterized by the coupling of nonverbal but nonetheless unambiguous indications of the presence of negative emotion with the refusal to discuss the scenario triggering those emotions and, when those emotions' source is unclear to the other party, occasionally the refusal to clarify it or even to identify that source at all. As a result, the perpetrator of the silent treatment denies the victim both the opportunity to negotiate an after-the-fact settlement of the grievance in question and the ability to modify his/her future behavior to avoid giving further offense. In especially severe cases, even if the victim gives in and accedes to the perpetrator's initial demands, the perpetrator may continue the silent treatment so as to deny the victim feedback indicating that those demands have been satisfied. The silent treatment thereby enables its perpetrator to cause hurt, obtain ongoing attention in the form of repeated attempts by the victim to restore dialogue, maintain a position of power through creating uncertainty over how long the verbal silence and associated impossibility of resolution will last, and derive the satisfaction that the perpetrator associates with each of these consequences.[13]

Love bombing

Love bombing has been used to describe the tactics used by pimps and gang members to control their victims.[14]

In an intimate relationship

Background

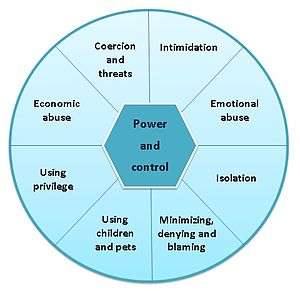

The power and control "wheel" was developed in 1982 by the Domestic Abuse Program in Minneapolis to explain the nature of abuse, to delineate the forms of abuse used to control another person, and to educate people with the goal of stopping violence and abuse. The model is used in many batterer intervention programs, and is known as the Duluth model.[15] Power and control is generally present with violent physical and sexual abuse.[16]

Control development

Often the abusers are initially attentive, charming and loving, gaining the trust of the individual that will ultimately become the victim, also known as the survivor. When there is a connection and a degree of trust, the abusers become unusually involved in their partner's feelings, thoughts and actions.[17] Next, they set petty rules and exhibit "pathological jealousy". A conditioning process begins with alternation of loving followed by abusive behavior. According to Counselling Survivors of Domestic Abuse, "These serve to confuse the survivor leading to potent conditioning processes that impact on the survivor's self-structure and cognitive schemas." The abuser projects responsibility for the abuse on to the victim, or survivor, and the denigration and negative projections become incorporated into the survivor's self-image.[17]

Traumatic bonding occurs as the result of ongoing cycles of abuse in which the intermittent reinforcement of reward and punishment creates powerful emotional bonds that are resistant to change.[3]

| Gain trust | Overinvolvement | Petty rules and jealousy | Manipulation, power and control | Traumatic bonding | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The potential abuser is attentive, loving, charming | |

The abuser becomes overly involved in the daily life and use of time | |

Rules begin to be inserted to begin control of the relationship. Jealousy is considered by the abuser to be "an act of love" | |

The victim is blamed for the abuser's behavior and becomes coerced and manipulated | |

Ongoing cycles of abuse can lead to traumatic bonding |

Tactics

Controlling abusers use multiple tactics to exert power and control over their partners. According to Jill Cory and Karen McAndless-Davis, authors of When Love Hurts: A Woman's Guide to Understanding Abuse in Relationships: Each of the tactics within the power and control wheel are used to "maintain power and control in the relationship. No matter what tactics your partner uses, the effect is to control and intimidate you or to influence you to feel that you do not have an equal voice in the relationship."[1]

Coercion and threats

A tool for exerting control and power is the use of threats and coercion. The victim may be subject to threats that they will be left, hurt, or reported to welfare. The abuser may threaten that they will commit suicide. They may also coerce them to perform illegal actions or to drop charges that they may have against their abuser.[20]

At its most effective, the abuser creates intimidation and fear through unpredictable and inconsistent behavior.[3] Absolute control may be sought by any of four types of sadists: explosive, enforcing, tyrannical or spineless sadists. The victims are at risk of anxiety, dissociation, depression, shame, low self-esteem and suicidal ideation.[21]

Intimidation

Abused individuals may be intimidated by the brandishing of weapons, destroying their property or other things, or using gestures or looks to create fear.[20]

Economic abuse

An effective means of ensuring control and power over another is to control their access to money. One method is to prevent the abusee from getting a job. Another is to control their access to money. This can be done by withholding information and access to family income, taking their money, requiring the person to ask for money, giving them an allowance, or filing a power of attorney or conservatorship, particularly in the case of economic abuse of the elderly.[20]

Emotional abuse

Emotional abuse include name-calling, playing mind games, putting the victim down, or humiliating the individual. The goals are to make the person feel bad about themselves, feel guilty or think that they are crazy.[20]

Isolation

Another element of psychological control is the isolation of the victim from the outside world.[16] Isolation includes controlling a person's social activity: who they see, who they talk to, where they go and any other method to limit their access to others. It may also include limiting what material is read.[20] It can include insisting on knowing where they are and requiring permission for medical care. The abuser exhibits hypersensitive and reactive jealousy.[16]

Minimizing, denying and blaming

The abuser may deny the abuse occurred to attempt to place the responsibility for their behavior on the victim. Minimizing concerns or the degree of the abuse is another aspect of this control.[20]

Using children and pets

Children may be used to exert control, by threatening to take the children or making them feel guilty about the children. It could include harassing them during visitation or using the children to relay messages. Another controlling tactic is abusing pets.[20]

Using privilege

Using "privilege" means that the abuser defines the roles in the relationship, makes the important decisions, treats the individual like a servant and acts like the "master of the castle".[20]

In the workplace

A power and control model has been developed for the workplace, divided into the following categories:[22]

- overt actions

- covert actions

- emotional control

- isolation

- economic control

- tactics

- restriction

- management privilege

Bullying

An essential prerequisite of bullying is the perception, by the bully or by others, of an imbalance of social or physical power.[23][24]

Workplace psychopaths

The authors of the book Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work describe a five phase model of how a typical workplace psychopath climbs to and maintains power:[25]

- Entry - psychopath will use highly developed social skills and charm to obtain employment into an organisation. At this stage it will be difficult to spot anything which is indicative of psychopathic behaviour, and as a new employee you might perceive the psychopath to be helpful and even benevolent.

- Assessment - psychopath will weigh you up according to your usefulness, and you could be recognised as either a pawn (who has some informal influence and will be easily manipulated) or a patron (who has formal power and will be used by the psychopath to protect against attacks)

- Manipulation - psychopath will create a scenario of “psychopathic fiction” where positive information about themselves and negative disinformation about others will be created, where your role as a part of a network of pawns or patrons will be utilised and you will be groomed into accepting the psychopath's agenda.

- Confrontation - the psychopath will use techniques of character assassination to maintain their agenda, and you will be either discarded as a pawn or used as a patron

- Ascension - your role as a patron in the psychopath’s quest for power will be discarded, and the psychopath will take for himself/herself a position of power and prestige from anyone who once supported them.

Caring professions

According to Field, bullies are attracted to the caring professions, such as medicine, by the opportunities to exercise power over vulnerable clients, and over vulnerable employees and students.[26]

Institutional abuse

Institutional abuse is the maltreatment of a person (often children or older adults) from a system of power.[27] This can range from acts similar to home-based child abuse, such as neglect, physical and sexual abuse, and hunger, to the effects of assistance programs working below acceptable service standards, or relying on harsh or unfair ways to modify behavior.[27]

Oppression

Oppression is the exercise of authority or power in a burdensome, cruel, or unjust manner.[28]

Zersetzung

The practice of repression in Zersetzung comprised extensive and secret methods of control and psychological manipulation, including personal relationships of the target, for which the Stasi relied on its network of informal collaborators,[29] (in German inoffizielle Mitarbeiter or IM), the State's power over institutions, and on operational psychology. Using targeted psychological attacks the Stasi tried to deprive a dissident of any chance of a "hostile action".

Sadistic personality disorder

Individuals with sadistic personality disorder derive pleasure from the distress caused by their aggressive, demeaning and cruel behavior towards others. Sadistic people have poor ability to control their reactions and become enraged by minor disturbances, with some sadists more abusive than others. They use a wide range of behaviors to control others, ranging from hostile glances to severe physical violence. Within the spectrum are cutting remarks, threats, humiliation, coercion, inappropriate control over others, restrictive of others' autonomy, hostile behavior and physical and sexual violence. Often the purpose of their behavior is to control and intimidate others.[30]

At the affective level, the sadist shares many of the critical features of the psychopath: they lack remorse for their controlling and exploitative behavior, they do not experience shame or guilt, and they are unable to empathize with their victims. They are cold hearted.— Adrian Raine and José Sanmartin, authors of Violence and Psychopathy[30]

The sadistic individual are likely rigid in their beliefs, intolerant of other races or other "out-groups", authoritarian, and malevolent. They may seek positions in which they are able to exert power over others, such as a judge, army sergeant or psychiatrist who misuse their positions of power to control or brutalize others. For instance, a psychiatrist may institutionalize a patient by misusing mental health legislation.[30]

Serial killers

The main objective for one type of serial killer is to gain and exert power over their victim. Such killers are sometimes abused as children, leaving them with feelings of powerlessness and inadequacy as adults. Many power- or control-motivated killers sexually abuse their victims, but they differ from hedonistic killers in that rape is not motivated by lust (as it would be with a lust murder) but as simply another form of dominating the victim.[31] (See article causes of sexual violence for the differences regarding anger rape, power rape, and sadistic rape.) Ted Bundy is an example of a power/control-oriented serial killer. He traveled around the United States seeking women to control.[32]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Jill Cory; Karen McAndless-Davis. When Love Hurts: A Woman's Guide to Understanding Abuse in Relationships. WomanKind Press; 1 January 2000. ISBN 978-0-9686016-0-0. p. 30.

- 1 2 Braiker, Harriet B. (2004). Who's Pulling Your Strings ? How to Break The Cycle of Manipulation. ISBN 0-07-144672-9.

- 1 2 3 Chrissie Sanderson. Counselling Survivors of Domestic Abuse. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 15 June 2008. ISBN 978-1-84642-811-1. p. 84.

- ↑ Kristin Glaser, in The Radical Therapist (Penguin 1974) p. 246

- ↑ Michelle N. Lafrance, Women and Depression (2009) p. 89

- ↑ Art Horn, Face It (2004) p. 53

- ↑ Robin Skynner/John Cleese, Families and how to survive them (London 1994) p. 208

- ↑ Robert Bly and Marion Woodman, The Maiden King (Dorset 1999) p. 141

- ↑ Andrew Holmes/Dan Wilson, Pains in the Office (2004) p. 56

- ↑ Martha Stout, The Sociopath Next Door (2005) p. 47

- 1 2 Johnson, R. Skip (16 August 2014). "Emotional Blackmail: Fear, Obligation and Guilt (FOG)". BPDFamily.com. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ↑ Susan Forward/Donna Frazier, Emotional Blackmail (London 1997) p. 28, 82, 145, 169

- ↑ Petra Boynton The Telegraph (26 Apr 2013) Silent treatment: how to snap him out of it

- ↑ Gangs and Girls: Understanding Juvenile Prostitution, Michel Dorais, Patrice Corriveau, McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, Jan 1, 2009, page 38

- ↑ Dr. Joan McClennen PhD. Social Work and Family Violence: Theories, Assessment, and Intervention. Springer Publishing Company; 8 February 2010. ISBN 978-0-8261-1133-3. p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. World Health Organization. 2013. ISBN 978-92-4-156462-5. p. 7.

- 1 2 Chrissie Sanderson. Counselling Survivors of Domestic Abuse. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 15 June 2008. ISBN 978-1-84642-811-1. p. 83.

- ↑ Dr. Joan McClennen PhD. Social Work and Family Violence: Theories, Assessment, and Intervention. Springer Publishing Company; 8 February 2010. ISBN 978-0-8261-1133-3. p. 148.

- ↑ Dr. Joan McClennen PhD. Social Work and Family Violence: Theories, Assessment, and Intervention. Springer Publishing Company; 8 February 2010. ISBN 978-0-8261-1133-3. p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Power and Control. Duluth Model. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ↑ Chrissie Sanderson. Counselling Survivors of Domestic Abuse. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 15 June 2008. ISBN 978-1-84642-811-1. p. 25.

- ↑ Power & Control in the Workplace American Institute on Domestic Violence

- ↑ "Children who are bullying or being bullied". Cambridgeshire County Council: Children and families. Cambridgeshire County Council. 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- ↑ Ericson, Nels (June 2001). "Addressing the Problem of Juvenile Bullying" (PDF). OJJDP Fact Sheet #FS-200127. U.S. Department of Justice: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. 27. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- ↑ Baibak, P; Hare, R. D Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work (2007)

- ↑ Field, T. (2002). "Bullying in medicine". BMJ. 324 (7340): 786. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7340.786/a.

- 1 2 Powers, J. L.; A. Mooney; M. Nunno (1990). "Institutional abuse: A review of the literature". Journal of Child and Youth Care. 4 (6): 81.

- ↑ definition from Merriam Webster Online.

- ↑ Federal Commissioner for the Records of the State Security Service of the former German Democratic Republic: The Unofficial Collaborators (IM) of the MfS

- 1 2 3 Adrian Raine; José Sanmartin. Violence and Psychopathy. Springer; 31 December 2001. ISBN 978-0-306-46669-4. p. 126–128.

- ↑ Egger, Steven A. (2000). "Why Serial Murderers Kill: An Overview". Contemporary Issues Companion: Serial Killers.

- ↑ Peck 2000, p. 255.

External links

- Sarah Strudwick (Nov 16, 2010) Dark Souls - Mind Games, Manipulation and Gaslighting