CyArk

| |

| Formation | 2003 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Ben Kacyra |

| Purpose | Digital preservation of cultural heritage sites and architecture |

| Headquarters | Oakland, California |

| Products | CyArk 3D Heritage Archive |

| Methods | Laser scanning, digital modeling |

| Website |

cyark |

CyArk is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization located in Oakland, California, United States. The organization's website refers to it as a "digital archive of the world’s heritage sites for preservation and education". Its official mission statement is “Digitally preserving cultural heritage sites through collecting, archiving and providing open access to data created by laser scanning, digital modeling, and other state-of-the-art technologies.”

CyArk’s founder, Ben Kacyra, stated during his speech at the 2011 TED Conference that the organization was created in response to increasing human and natural threats to heritage sites, and to ensure the “collective human memory” is not lost while making it available through modern dissemination tools like the internet and mobile platforms.[1]

The organization is known for its work with a number of partners in producing high-quality digital scanning of World Heritage Sites, such as Angkor Wat, Pompeii, Chichen Itza, the Eastern Qing tombs, Nineveh, the Antonine Wall, Mount Rushmore, and many others.[2][3][4][5]

The organization seeks to preserve 500 World Heritage Sites in the next five years.[6]

History

CyArk was founded in 2003 by Iraqi expatriate and civil engineer Ben Kacyra. In the 1990s, Kacyra was instrumental in the invention and marketing of the first truly portable laser scanner. The scanner, called the Cyrax, was designed for surveying purposes, and was produced by Cyra Technologies.[7]

In 2001, Cyra Technologies and all rights to the invention were sold to the Swiss firm Leica Geosystems.[8]

After sale of the company, Ben Kacyra dedicated his energy to using the new technology to document archaeological and cultural heritage resources, and to the CyArk organization.[9]

CyArk’s primary focus has been the documentation and digital preservation of threatened ancient and historical architecture. This architecture includes sites such as Colorado's Mesa Verde, Italy's Pompeii, Wyoming’s Fort Laramie, and Kacyra's native Mosul in Iraq – also known as the biblical Assyrian city of Nineveh.

CyArk has generated a fairly large amount of publicity since its inception. Initially, this was in part due to the relevance of Kacyra's life story to the ongoing Iraq War, during which much of the country's cultural patrimony was destroyed amidst a spasm of looting and heavy military damage to important historical sites such as Babylon and Samarra. As the public face of the CyArk organization, Ben Kacyra became a popular speaker at conferences such as Google’s Zeitgeist (2008), and TEDGlobal (2011), describing his life story and the potential of digital preservation to save the “collective treasure” of global heritage. In recent years, however, he has taken on more of an advisory role, while the independent non-profit organization CyArk has gathered considerable momentum.

"In October of 2013, CyArk launched the CyArk 500 Challenge."[6] The organization announced that it seeks to "digitally preserve 500 heritage sites in five years."[10]

As of 2014, CyArk has become a major entity in the historic preservationist and cultural resource/heritage management communities. The 2014 CyArk 500 Annual Summit was held at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C. The theme was "Democratising cultural heritage: Enabling access to information, technology and support."[10]

Project focus

According to CyArk's mission statement, the organization is

dedicated to the preservation of cultural heritage sites through the CyArk 3D Heritage Archive, an internet archive which is the repository for heritage site data developed through laser scanning, digital modeling, and other state-of-the-art spatial technologies.

CyArk's digital data may be useful for professionals monitoring and managing gradual architectural deterioration at cultural sites.[11] This data could also make it possible to generate blueprints for reconstruction following catastrophic events, such as the Afghan Taliban’s notorious demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 or the 2010 destruction by suspected arson of the Royal Tombs of Kasubi, Uganda. The Kasubi Tombs were digitally preserved by CyArk a year before their demise, providing a lasting digital record and potential blueprint for reconstruction.[12]

CyArk offers a publicly accessible web archive for the archaeological sites it has studied. The archive includes a short film introduction for each site, a slideshow of site history, and information about the digital preservation process used. A site plan displays geo-located multimedia, which is also accessible in an image gallery, along with three-dimensional images of site details such as rooms and profiles, and computer-generated reconstructions. The three dimensional images are often taken from a "point cloud" image showing the raw scan data.[13] CyArk has granted permission for reuse of some of the images through a Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike license.

According to CyArk’s online mission statement, the dissemination of free digital content about heritage sites can help encourage additional visits by tourists, and invigorate communities with revenue from cultural tourism. Youth and educators will benefit from free, publicly accessible historical and site information, including some Creative Commons-licensed content. And finally, the creation of digital records ensures not only that the sites will never be lost forever; it also provides a digital resource to facilitate the continued mining of information over time as technologies and methods of information extraction evolve.

Selected list of projects

- Ancient Merv, a major crossroads along the ancient silk road in Turkmenistan

- Ancient Thebes and the Ramesseum/Necropolis of Ramses II, Egypt

- Angkor Wat’s western causeway and Banteay Kdei areas, Cambodia

- The Bab al-Barqiyya Gate, a portion of the Ayyubid Wall in Cairo, Egypt

- A Carmelite Church in Weissenburg, Germany

- Beauvais Cathedral, a Gothic masterwork in France

- Chavin De Huantar, 3500-year-old capital of the Chavin culture, Peru [14]

- Chichen Itza, ancient Yucatán Maya center and pilgrimage site, Mexico [2]

- Deadwood, the legendary Old West city in South Dakota, United States

- Fort Conger, a 19th-century Arctic exploration camp located on Northeastern Ellesmere Island, Nunavut, Canada.

- Fort Laramie, historic center of the Plains Indian Wars and the Oregon Trail, United States

- The Hypogeum of the Volumnis, an intact Etruscan tomb near Perugia, Italy

- Mesa Verde’s Spruce Tree House, Square Tower House, and Fire Temple, ancestral Puebloan cliff structures in Colorado, United States [13]

- Monte Alban, the capital of the ancient Zapotecs of Oaxaca, Mexico [9][15]

- Nineveh, imperial capital of the Assyrian Empire, Iraq

- Piazza Del Duomo’s Baptistery, Cathedral, and Campanile (also known as the Leaning Tower of Pisa), Italy

- Pompeii, ancient Roman city buried under the volcanic eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, Italy. The CyArk website states that this project was also the first time laser scanning was used to document a cultural heritage site.

- The Presidio of San Francisco, a historic military base, United States

- Qal’at al-Bahrain, a 14th-century Portuguese fort built atop the remains of the ancient Dilmun civilization’s hilltop capitol, Bahrain

- Rani ki vav, the largest stepwell in India, in the town of Patan, Gujarat [4]

- Rapa Nui (Easter Island), scans of the famous monuments and lesser-known structures of this very isolated Polynesian culture site, Chile

- Roman Baths of Weissenburg, one of the best-preserved examples of Thermae along the remote borders of the Roman Empire, Germany

- Royal Kasubi Tombs, culturally vital mausoleum of the last four Bugandan Kings, Uganda. The Tombs were scanned and documented by CyArk in 2009 then largely destroyed by a fire in 2010, and data from the scans will be used for reconstruction efforts.

- Saint Sebald Church, a medieval cathedral in Nuremberg that was heavily damaged during WWII but retained enough original architecture to allow for digital reconstructions, Germany

- Church and Cloister of Saint-Trophime, a former cathedral in Arles, France that contains some of the world’s most notable Romanesque facades

- The Pelourinho of Salvador da Bahia, historic downtown district of Brazil’s original capitol

- Stone Bridge of Regensburg, 800-year-old bridge across the Danube, Germany

- Tambo Colorado, an adobe-built strategic center of the ancient Inca empire, Peru

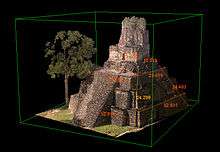

- Tikal, one of the most important and longest-occupied cities of the ancient Maya world, Guatemala

- Tudor Place, a Federal-style neoclassical mansion that served as home to six generations of George Washington’s immediate descendants

The CyArk website also offers a world map of the hazards which global heritage sites face, such as earthquakes and sea level rise due to global warming.

Funding and partnerships

Initially, CyArk was fully supported by the Kacyra family and their Kacyra Family Foundation.[7]

CyArk is now primarily funded through individual project funding, corporate in-kind support, and foundation grants/donations. Corporate funders as of 2014 include Microsoft, IBM, Iron Mountain, Autodesk, and Trimble Navigation.[6]

CyArk has also established working relationships with project partners in engineering, media, and academia, including Christofori und Partner and PBS. At UC Berkeley, the organization coordinated an internship program with the department of Anthropology in 2006-2007. CyArk is currently an approved work-study employer for Cal students.

As of October 2011, the already-existing partnerships with the United States’ National Park Service (NPS), the United Kingdom’s Historic Scotland (HS), World Monuments Fund, and Mexico’s Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Historia (INAH) had been greatly expanded,[16] with upcoming projects that include Mexico’s Teotihuacan,[17] Scotland’s Rosslyn Chapel,[18] Iraq’s Babylon, and the U.S.’ Mount Rushmore National Memorial.[3][19]

References

- ↑ Video of Ben Kacyra's speech at the TED 2011 conference

- 1 2 Brown, John; Elizabeth Lee (2008). "Ancient History Meets New Technology". Professional Surveyor Magazine (March). Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 Lee, Elizabeth (October 2010). "Scanning Rushmore - Digitizing the Legacy". The American Surveyor. Volume 7 (No. 7). pp. 10–19. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 Luccio, Matteo (2013). "Surveying Cultural Heritage". Professional Surveyor Magazine (July). Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ↑ "CyArk Projects". CyArk. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 3 Cheves, Marc (2014-10-01). "Monumental Challenge: Ben Kacyra's Remarkable Perseverance". LiDAR News. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 Abate, Tom (2007-07-22). "Laser mapping tool traces ancient sites - Device made for contractors helps archaeologists create first-ever digital blueprints". SFGate - Innovations. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ↑ "History". Leica Geosystems. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 Powell, Eric A (May–June 2009). "The Past in High-Def". Archaeology Magazine. Volume 62 (No 3). Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 "CyArk 500 Annual Summit 2014". Digital meets Culture. 2014-10-07. Retrieved 2014-10-09.

- ↑ Interview with Ben Kacyra in National Geographic (October 2010)

- ↑ Preston, Elizabeth (December 2011). "The Big Idea - Laser Preservation". National Geographic Magazine. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- 1 2 PBS' Wired Science segment on CyArk, November 2007

- ↑ Risvetski, John (2006). "Laser Scanning for Cultural Heritage Applications". Professional Surveyor Magazine (March). Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ↑ Monte Alban, CyArk website

- ↑ Updates from CyArk, 2011, CyArk website

- ↑ Teotihuacan, CyArk website

- ↑ Rosslyn Chapel, CyArk website

- ↑ Mount Rushmore, CyArk website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to CyArk. |

- CyArk Website

- Ancient Wonders captured in 3D, a TED talk by Ben Kacyra

- Video of Ben Kacyra's presentation on CyArk at Google's Annual partner forum, Zeitgeist, in 2008

- Hazard map showing variable sea level rise and earthquake impacts, developed by CyArk to demonstrate potential impact of climate change (and earthquakes) on World Heritage Sites

- F. Limp et al. 2011 'Developing a 3-D Digital Heritage Ecosystem: from object to representation and the role of a virtual museum in the 21st century', Internet Archaeology 30.

- AIArchitect article on Cyark Work at Tudor Place, May 2007

- The Archaeology Channel video on the CyArk work at Pompeii