Archaeological looting in Iraq

History

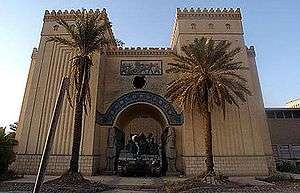

Looting of ancient artifacts has a long tradition. As early as 1884, laws passed in Mesopotamia about moving and destroying antiquities.[2] By the end of WW1, British-occupied Mesopotamia had created protections for archeological sites where looting was beginning to become a problem.[3] They established an absolute prohibition on exporting antiquities.[4] The British Museum was responsible for the sites and museums across Iraq during this time period. Gertrude Bell, well known for drawing the Iraq borders, excavated many sites around Iraq and created what is now the National Museum of Iraq.[5]

By the mid 1920s the black market for antiquities was growing and looting began in all sites where antiquities could be found. After Iraq was independent of Britain the absolute ban on antiquity exports was lifted. Until the mid 1970s Iraq was one of very few countries to not prohibit external trade in antiquities.[6] This made Iraq attractive to looters and black market collectors from around the globe. The result of the first Gulf War was that at least 4000 artifacts were looted from Iraq sites.[7] Uprisings that followed the war also resulted in 9 of 13 regional museums being looted and burned.[8] This was just a preview for what would once again happen after the 2003 war. Since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, archaeological looting has become an even greater problem. Though some sites, such as Ur and Nippur, were officially protected by US and Coalition forces, most were not.

Saddam Hussein treasured his national heritage immensely and acted to defend these sites and the artifacts within them. Hussein came into power in 1979 as the fifth president of Iraq. He believed that the past of Iraq was important to his national campaign and his regime actually doubled the national budget for archeology and heritage creating museums and protecting sites all over Iraq.[9] It wasn’t until his party the Ba’athists was under pressure in the 1990s that looting become a large problem once again for Iraq.[10] By 2000 looting had become so rampant that the workers of the sites were even looting their own workplaces.[11] With the fall of Saddam's government on 9 April 2003, archaeological sites were left completely open to looting.

Failure to protect before the 2003 Invasion

Before the 2003 invasion by United States forces, the US government created an invasion and post-war plan for Iraq. The US has been heavily criticized in the media and academic writings for not adequately planning protections for culture and antiquities.[12] This looting of the National Museum of Iraq and of hundreds of archeological sites around the country was not prevented.[13] At the time of war planning it was the Secretary of Defence Donald Rumsfeld decided on a fast invasion with fewer troops, resulting in inadequate protection of buildings and cultural sites.

American troops and commanders did not prioritize security for cultural sites around Iraq.[14] Peacekeeping was seen as a lesser job then physically fighting in combat and President Bush’s suspension of former president Clinton’s policies for peacekeeping not only backed up this thought but also made the US’s duties to restore public order unclear.[15] American troops in Iraq didn’t trust Iraqi power of any kind meaning instead of using and training Iraqi police, the US military took matters of security and policing into their own hands.[16] Essentially the US would act as peacekeepers to train a national army and police force. Special Forces teams would work with regional warlords to keep control of their territories.[17] Allowing warlords to police their own areas has been credited with being a disastrous plan for the archeological sites in particular.[18]

Arthur Houghton had an interest and some expertise in cultural heritage and was one of the first to wonder what the pre-war plan was for Iraqi culture. He had worked in the State Department as a Foreign Service officer, as an international policy analyst for the White house and also served at an acting curator for the Getty Museum.[19] In late spring 2002, Houghton was approached by Ashton Hawkins, former Executive Vice President and Counsel to the Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum, and was asked to find out what was being done by officials to secure heritage sites in the upcoming war in Iraq.[20] Houghton could find no one designated with the task of protection and preservation of culture in Iraq.[21]

There had been a secret Future of Iraq Project since October 2001, with clearance from the Pentagon. However, even under this Project no specific person had taken up responsibility of culture.[22] Even archeological organizations in the US hadn’t noticed the issue until late 2002. Likewise when the US Agency for Cultural Development (USAID) met with estimated 150 NGO’s not one brought up protection of cultural heritage.[23] UNESCO had in fact, after the Gulf War in 1991, attempted to go into Iraq and assess the damage to cultural sites but they were not allowed to enter the country.[24] UNESCO then focused, for the next decade, on reconstruction after the fact rather than prevention measures.[25]

Within the US military, Civil Affairs (CA) forces were important to the protection of culture and, as they were mostly reservists, included experts in a variety of areas including archeology.[26] The plan was to spread the expertise among fighting forces in order to warn them of cultural sites in the area.[27] However, CA was left out of pre-war planning until January 2003, when it was too late to be of any real significant help. The CA had to prioritize the small amount of CA troops to what they thought was necessary, which inevitably wasn’t culture.[28] The CA did, however, pull the only two archeologists in Civil Affairs to be on a culture team, Maj. Chris Varhola and Capt. William Sumner.[29] These two men, however, in the end were sent to other places when the conflict began. Varhola was needed to prepare for the refugee crises that never arrived and Sumner was reassigned to guard a zoo after pushing his advisor too hard on antiquities issues.[30] Any protection of culture, sites or buildings were stopped due to the priorities of other matters. Essentially no one who had archeological expertise was senior enough to get anything done.[31]

Another branch of the US government that had interest in culture was the Foreign Area Offices (FAO). Unfortunately though, they were focused on customs and attitudes not at all about archeological sites.[32] Something that was accomplished was the creation of a no-strike list created by Maj. Varhola just like two archeologists before him had done during the 1991 Gulf War which had a great outcome of saving antiquities from bombing.[33]

One piece of international law that is important for this conflict is the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, this Convention states that parties in conflict must “under take to prohibit, prevent and, if necessary, put a stop to any form of theft, pillage or misappropriation of, and any act of vandalism directed against, cultural property.[34]” This provision was constructed for the parties actually in combat within the war and not civilians within their own state. As the upcoming years would prove, there are exceptions to this Convention and they would result in Americans firing on the Iraq National Museum.

By fall 2002, post-war planning was sporadic and improvised. The cultural planning aspect needed to have leadership that it never got.[35] Deputy Assistant under the Security of Defense, Joseph Collins, recalls some forces spent more time working on projects that ended up not being needed like a refugee crises plan. He says he can’t remember if there was even an organizational plans to solve specific issues.[36]

The first known effort by cultural interests to contact US officials was October 2002. After a meeting of powerful players in culture, Houghton sent a letter asking for departments to tell forces to avoid damaging monuments, soldiers were to respect the integrity of sites, and lastly to work quickly to get the antiquities services in Iraq up and running again.[37] Following this, the Archeological Institute of America (AIA) also sent a similar letter to the Pentagon in December 2002 asking for governments to take action to prevent looting in the aftermath of the war.[38] As 2002 came to an end the media and government were only broadcasting the good done by the troops in not destroying cultural heritage themselves but not on the looting done by people in Iraq and the Americans duty to protect the antiquities.[39]

Large scale looting

When the looting of the National Iraq Museum became known, experts from around the globe started planning to remedy the situation.[40] McGuire Gibson, one of the leading archeologists and experts on Mesopotamia explained to the Office of Reconstruction and Humanitarian Assistance (OHRA) that the looted museum artifacts were only a small part of what archeological digs around the country held.[41] Perhaps 25 thousand of an estimated half million sites were registered. OHRA had no resources to address this problem. Gibson had suggested helicopter surveys to determine the scale of looted sites.[42] By April 24, 2003, looting had taken place in Umma, Umm al-Hafriyat, Umm al-Aqarib, Bismaya, Larsa, and Bad-tibira, most of were unguarded.[43] Most looting was by workers once employed by the now disbanded State Board of Antiquities and Heritage.[44] A local tribe was guarding the World Heritage Site of Hatra although others were unsupervised.[45]

By May 2003, international work began on the already looted museum but not on other sites.[46] The US military conducted a raid in May on Umma where they found hundreds of trenches with many looters all over the site.[47] On May 7, the Bush Administration replaced Gen. Jay Garner with L. Paul Bremer who was given more power and banned high-ranking Ba’ath Party members from government jobs and disbanded the remains of the Iraqi army.[48] Any guards at archeological sites were unpaid for months and they were not allowed to carry guns.[49] Now, instead of dealing with civilian looters, these unarmed guards were dealing with large mobs of armed people.[50]

At the end of May 2003, it finally became clear how badly the sites were looted when a trip sponsored by National Geographic went out to assess the damage.[51] There was a northern and southern team to assess the post-conflict damage by land.[52] They found the famous sites such as Babylon, Hatra, Nimrud and Ur were under US military control.[53] Lesser known sites were completely unguarded and the responsible Civil Affairs teams didn’t even know where they were.[54] Every place the National Geographic team saw, except one that was guarded by barbed wire, had been damaged.[55]

Gibson was part of the northern National Geographic team and he sent a report to the White House science advisor John Marburger.[56] Other archeological experts in both the US and Britain were waiting for invitations to go to Iraq and help. After Gibson’s report they were given invitations to create a team in Iraq.[57]

Early July 2003, UNESCO revealed that looting was still happening at sites across the country.[58] Other military services such as Japanese and Dutch troops offered assistance but were ignored.[59] In July 8, a new security guard force known as the Iraqi Facility Protection Service (FPS) was established to protect sites all around the country in co-operation with the US military.[60] A week later, the State Department announced it was forming a group to assist in the rebuilding of Iraq’s cultural heritage.[61]

These announcements had no effect on the looting and illegal export of artifacts. McGuire Gibson on September 11, 2003 wrote to a military geographer, "The continuing destruction of sites all over southern Iraq and the theft of thousands of artifacts every week, with no visible effort on part of the US authorities, makes the question of ethical behaviour by museums pointless. Your unit of the Pentagon is capable of demonstrating the location and expansion of illegal digging. Are you at least doing that much?"[62]

Aftermath

It is impossible to discover exactly how much destruction to archeological sites has happened since the 2003 invasion.[63] As late as 2004, US military maps still did not show archeological sites.[64] Archeologist Elizabeth Stone purchased satellite images of the seven thousand square kilometers in Iraq that contain many known sites.[65] She counted 1 837 new holes by comparing 2001-2002 with 2003 images.[66] Looters concentrated on sites that had the most marketable artifacts. Estimates of the number of looted artifacts from 2003-2005 are from 400 000 to 600 000 items. This number is 30-40 times greater than the number of artifacts stolen from the museum.[67] Britain alone between 2004-2006 seized 3-4 tons of plundered artifacts.[68]

Some artifacts have been recovered by accident. An archeologist was watching a home decorating show when he saw a second century stone head from Hatra sitting on the decorator’s mantle.[69] The illegal black market for goods became so saturated that prices in the market were going down after 2003 according to an antiquities researcher specializing in illicit dealings.[70]

Revenue from looted antiquities is estimated by the Archeological Institute of America to amount to between $10 to $20 million annually.[71] Terrorist and rebel groups have a long history of using stolen artifacts to finance their operations.[72]

By the end of 2003, 1 900 Iraqi antiquities had been confiscated from bordering countries: 1 450 in Jordan, 36 in Syria, 38 in Kuwait and 18 in Saudi Arabia.[73]

Marine Corps reservist Matthew Boulay witnessed illicit trading even on U.S. military bases.[74] Flea markets authorized by the camp commanders included a booth with antiquities for $20, $40 or $100 each.[75] Boulay asked Gibson and was told that these artifacts were real. Gibson asked Boulay to ask the base commander to stop these sales. When Boulay informed his platoon commander he got a “cease and desist” order forbidding any more emails about the issue to anyone.[76]

Other institutes from America and around the world have contributed to protect sites in Iraq but this is still not enough. The US started teaching military personnel headed for Iraq the importance of cultural heritage and site preservation, but not how to stop civilian looting.[77] Donny George who was an employee at the Iraq National Museum was appointed to Director of Museums in 2004, and by summer 2006, a force of 1400 guards were at sites around the country.[78]

Sites affected

- Adab - an ancient city plagued by hundreds of looters.

- Babylon - saw the construction of "a 150-hectare camp for 2,000 troops. In the process the 2,500-year-old brick pavement to the Ishtar Gate was smashed by tanks and the gate itself damaged. The archaeology-rich subsoil was bulldozed to fill sandbags, and large areas covered in compacted gravel for helipads and car parks. Babylon is being rendered archaeologically barren".[79]

- Hatra - looters with stonecutters have stolen elements of friezes and reliefs straight off the ancient architecture here.

- Isin - over two hundred looters' pits are organized around the former site of the Temple of Gula; countless artifacts have been removed from the site here, including innumerable cuneiform tablets, cylinder seals, and votive tablets, some of which could sell for as much as $30,000.

- Nimrud - home of the palace of Assurnasirpal II and described by the Old Testament as the "principal city" of Assyria, Nimrud is one of the few sites that is militarily protected. However, weeks before the arrival of the site's US guards, looters attacked the friezes and statues with stonecutting tools, stealing images distinctly belonging to Nimrud, and thus unmistakenly known to any potential buyers to be stolen; the items have been sold, presumably, nevertheless. Those few looters that managed to break into this site despite its protection have given every indication that they know precisely what they are looking for, where to find it, and how to get at it. Like many looters throughout Iraq and across the world, they have presumably been hired to obtain specific images; this separates them from the looters who dig up and sell whatever they can find.

- Nineveh - one of the more thoroughly researched sites, experts have little difficulty identifying objects stolen from Nineveh. The site was severely looted and damaged nevertheless after the first Gulf War, and chunks of its unique and ancient friezes have appeared on the European and American art markets.

- Nippur - the great ziggurat here has only three major looters' pits cut into it, which are the first in over forty years of valuable research and excavation.

- Umma - looters descended upon the site as soon as Coalition bombing began; the site is now pockmarked with hundreds of ditches and pits. When archaeologists "tried to remove vulnerable carvings from the ancient city of Umma to Baghdad, they found gangs of looters already in place with bulldozers, dump trucks and AK47s".

- Ur - one of the few sites protected by a US military presence. According to Simon Jenkins, "its walls are pockmarked with wartime shrapnel and a blockhouse is being built over an adjacent archaeological site".

See also

- Illicit antiquities

- Looted art

- Art theft

- Iraq Museum

- Mosul Museum

- Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL or ISIS in 2014-2015

References

- ↑ "Art Museums in Asia". TheArtwolf.com. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 2.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 7.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 10.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 12.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 20.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 22.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 23.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 22.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 23.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 27.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 30.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 32.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 33.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 35.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 36.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 40.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 41.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 41.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 46.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 48.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 48.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 124.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 124.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 124.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 124.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 125.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 126.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 127.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 127.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 127.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 128.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 128.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 128.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 128.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 128.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 129.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 131.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 131.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 131.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 132.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 132.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 133.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 136.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 136.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 137.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 137.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 137.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 25.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 138.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 138.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 138.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 132.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 139.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 139.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 140.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 140.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 140.

- ↑ Rothfield, Lawrence (2009). The Rape of Mesopotamia. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 147.

- ↑ (Simon Jenkins in The Guardian, 8 June 2007).

- Atwood, Roger (2004). Stealing History: Tomb Raiders, Smugglers, and the Looting of the Ancient World. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Bogdanos, Matthew. Thieves of Baghdad: One Marine's Passion to Recover the World's Greatest Stolen Treasures. Bloomsbury USA (October 26, 2005) ISBN 1-58234-645-3

- Global Heritage Fund,

- 'Looting of ancient sites threatens Iraqi heritage 6/29/2006

- U.S.-Led Troops Have Damaged Babylon, British Museum Says, New York Times article

- Zainab Bahrani. 2004. Lawless in Mesopotamia. Natural History 113(2):44-49

- Farchakh, Joanne The massacre of Mesopotamian archaeology: Looting in Iraq is out of control, Tuesday, September 21, 2004

- The massacre of Mesopotamian archaeology

- Rothfield, Lawrence. The Rape of Mesopotamia behind the Looting of the Iraq Museum. Chicago: U of Chicago, 2009. Print.

External links

- 2003 UN Resolutions - Resolution 1483 concerns Iraq

- "The Archaeological Map of Iraq" is a map from 1967 that shows all of the archaeological sites in Iraq