Damara people

|

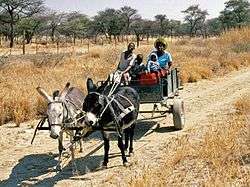

Damara people in Damaraland, Namibia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 100,000 (1996)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Khoekhoe (coll. Damara) | |

| Religion | |

| Both African Religion and Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Nama, Kwisi, Kwadi, Cimba |

The Damara, plural Damaran (Khoekhoegowab: ǂNūkhoen, literally Black people, German: Berg Damara, referring to their extended stay in hilly and mountainous sites, also called at various times the Daman or the Damaqua) are an ethnic group who make up 8.5% of Namibia's population. They speak the Khoekhoe language (like the Nama people) and the majority live in the northwestern regions of Namibia, however they are also found widely across the rest of the country. They have no known cultural relationship with any of the other tribes anywhere else in Africa,[2] and very little is known of their origin. It has been proposed that the Damara are a remnant population of south-western Africa hunter-gatherers, otherwise only represented by the Cimba, Kwisi, and Kwadi, who adopted the Khoekhoe language of the immigrant Nama people.[3]

Their name in their own language is the "Daman" (where the "-n" is just the Khoekhoe plural ending). The name "Damaqua" stems from the addition of the Khoekhoe suffix "-qua/khwa" meaning "people" (found in the names of other Southern African peoples like the Namaqua and the Griqua).[4]

Prior to 1870 the hunter-gatherer Damaran occupied most of central Namibia they used to practice pastoralism with sheep and cattle, but were also agriculturalist planting pumpkins, corn, tobacco. The Damaran were also copper-smiths known for their ability to melt copper and used to make ornaments, jewelry, knives and spear heads out of iron. The Damaran just like the Sān believed in communal ownership of land meaning that no individual owned land as God had given land to everyone. Not to for one to own good grazing land and the other to scavenge for land but that everyone live in harmony. It was for this reason that many were displaced when the Nama and Herero began to occupy this area in search of better grazing. Thereafter the Damara were dominated by the Namaqua and the Herero, most living as servants in their households.[2]

In 1960, the South African government forced the Damara into the bantustan of Damaraland, an area of poor soil and irregular rainfall. About half of their numbers still occupy Damaraland.

Mythology

The supreme deity of the Damaran (ǂNūkhoen) is ǁGamab, also referred to as ǁGammāb (provider of water), ǁGauna (Sān), ǁGaunab (Khoekhoe) and Haukhoin (Khoekhoe: foreigners) by the Khoekhoe.

He lives in a high heaven, even above the heaven of the stars. ǁGamab, from ǁGam, Khoekhoe: water, and mā, Khoekhoe: give is provider of the water and thus associated with the rising clouds, thunder, lightning and water. He ensured the annual renewal of nature being the cycle of the seasons and supplied game animals to the ǃgarob (Khoekhoe: veld) and the Damaran. One of his chief responsibilities is to warrant the growth of crops.

ǁGamab is also the God of Death, directing the fate of mankind. He shoots arrows at humans from his place above the skies and those struck fall ill and die. After death, the souls of the dead make their way to ǁGamab's village in the heaven above stars and gather around him at a ritual fire. Then he offers them a drink from a bowl of liquid fat to drink, as a reward.

ǁGamab's arch-enemy is the evil ǁGaunab.[4]

History

Since time immemorial, before the Nama migration from Southern Africa into what is today known as Namibia, and even before the arrival of the Bantu groups from North and Eastern Africa to the present-day Namibia the Damaran were living in this south-western part of Africa.

According to written accounts of the history of the Damaran which dates back to the leadership of the Damaras as far back as the 14th century (1390), substantiated by archaeological and ethnological evidence reflected to those records, the Damaran next to the Sān, are the first inhabitants of what is today known as Namibia. Oral tradition has it that the Damaran came to Namibia from ǁKhaus (Equatorial Rainforest) through ǃĀǂkhib centuries ago.

The Damaran initially settled between Huriǂnaub (Kunene River) and ǃGûǁōb (Kavango River), before entering what later-on centuries long after became known as ǀNaweǃhūb (Ovamboland). The Damaran moved southwards and were living peacefully as a single group in the area that is a stone’s throw and an eagle’s flight in the surrounding of Dâureb (Brandberg Mountain), Paresis Mountains, ǃHōb (Waterberg), the Omatako Mountains, Otavi Mountains and ǃOeǂgâb (Erongo Mountains). Oral and written historical records have it that intruders, reportedly under the leadership of a certain Mukumbi (Mûtsixubi) invaded that area in 1600, and clashed with the Damaran.

The Damaran dispersed in splinter groups as a result of the aftermath of this battle wherein the then Damara Gaob (King), Gaob ǀNarimab succumbed due to injuries sustained in the battle. The Damara, besides the ǀGowanîn, splinter groups then settled all over the country in areas where there was an abundant water and shelter in the form of mountains.

Remnants of the group that was led by Gaob ǀNarimab who dispersed moved eastwards and settled in the ǀGowas, also known as ǀŪmâs (Kalahari Desert) and got the name ǀGowanîn (Damaran of the Kalahari- later referred to as the Sand Kaffers by the imperialist Germans). Another group fled to mountainous central Namibia seeking shelter in ǀKhomas (Khomas Hochland), ǃAoǁaexas Mountains, ǂĒros (Eros Mountains) and ǀAu-ās (Auas Mountains) and became known as the ǀKhomanin (Damaran of the [ǀKhomas] mountains), later referred to as the Berg Damara.

The group that remained in and around ǃOeǂgâb (Erongo Mountains) and settled nearby present-day ǀÂǂgmmes (Okombahe) got to be known as the ǃOeǂgân (Damaran of the Erongo Mountain)

There were also two other groups that moved down the Tsoaxub (Swakop River) and ǃKhuiseb (Kuiseb River) respectively, namely the Tsoaxudaman and the ǃKhuisedaman.

Another group, the |Gaiodaman, moved towards the area of ǃKhuidiǁgams (Omaruru) and Parase!homgu (Paresis Mountains), and later-on moved back to area west of ǃHob (Waterberg). During the 1904 wars with the German colonial forces, some members of the ǀGaiodaman fled with the Ovaherero to Piriǃhūb (Botswana), whereas some settled at ǀŪgowas in the vicinity of ǃHob (Waterberg Mountain).

The major group of Damaras fled down towards the south, as far as the ǃGarib (Orange River) and settled in that area, and installed Gaob !Gariseb as their leader. This group moved back northwards around 1670, and settled at ǂKhanubes, wherefrom they moved and split into two groups, one of which settled in the vicinity of ǂAixorobes (Tsumeb) and the other one led by Gaob ǀNarirab settled at |Haigomab!gaus, south-east of Otjituuo. The latter-mentioned group split up in four (4) factions:

- One group moved to the ǃHoaruseb River, and systematically down towards the Atlantic Ocean following the said river and settling on its banks, and they became known as the ǃNaranin and ǃHoarusedaman respectively.

- The other group moved to the ǁHuanib River, and inhabited the area of ǃNani|audi (Sesfontein), and was called by the name ǁHuanidaman.

- The third faction moved towards the Dâureb (Brandberg) and got the name Dâuredaman and ǃNamidaman.

- The last faction moved towards Anibira-āhes (Fransfontein), and Aroǃhūb area, and they were later joined by the ǂAodaman who moved thereto from the Paresis Mountains.

The remainder of clans not mentioned above came into existence as a result of fractions in they already mentioned clans.

Kings

- Gaob ǁAruseb (1640–1700)- ǂKhanubes (Okanjande) in the vicinity of ǃHob (Waterberg)

- Gaob ǀNarimab (1665–1715)- Gamaǂhiras (Otjimbamba)

- Gaob ǃGariseb (1685–1710)- Guxanus (near Waterberg) and ǂKhanubes (Okanjande)

- Gaob ǀNawabeb (1740- 1790)- ǂKhanubes (Okanjande)

- Gaob Xamseb (1790–1812)- ǀAeǁgams (Windhoek)

- Kai Gaob ǃGausib ǁGuruseb (1790- 1812)- ǂGans (Gamsberg)

- Gaob Abraham ǁGuruseb (1812– 1865)- ǂGans (Gamsberg) and (1866–1880)- ǀÂǂgommes (Okombahe)

- Gaob Cornelius Goreseb (1880– 1910)- ǀÂǂgommes (Okombahe)

- Gaob Judas Goreseb (1910–1953)

- Gaob David Goreseb (1953–1977)

- Gaob Justus ǀUruhe ǁGaroëb (1977–present)

Clans

The Damara consist of 33 clans:

- Animîn: lit. Let them say/ the birds say- In the vicinity of ǃNoagutsaub, commonly known as Kaiǁkhaes (Okahandja).

- Aoguwun: lit. Tiger eye stones/ Sheep rams- To the south of ǂGaios commonly known as ǃNaniǀaus (Sesfontein) in Gaogob (Kaokoveld). The Aoguwun are also known as the Aogūdaman.

- Arodaman: lit. Damaras of the Sandveldt- In and around ǃHōb also known as Apabeb (Waterberg). The Arodaman later shared their land with the Herero (Kavazembi) who arrived much later.

- Aumîn: lit. Bitter words and blessings- To the north and east of ǃHōb also known as Apabeb (Waterberg).

- Auodaman: lit. Named after a medicinal plant endemic to the Auos Mountains- Down the Auob River around ǃAris (Steenbok).

- Auridaman: lit. Damaras of Aurib- Aurib is an arid land to the east of Gamaǂhâb (Kamanjab). To the east of Gamaǂhâb (Kamanjab).

- Danidaman: : lit Honey Damaras- To the east of Tsawiǀaus (Otavi). The Danidaman have intermingled with the Haiǁom and ǀNawen (Aawambo) who arrived much later.

- Dâuredaman: lit. Damaras of the Branberg- Dâureb is Khoekhoegowab for Brandberg. In the vicinity of Dâureb (Brandberg) and are also known as the Dâunadaman.

- Hâkodaman: lit. Damaras of the Hakos Mountains- The Khoekhoegowab name for the Hakos Mountain is Hâkos. In the Hâko Mountains between Aous and ǂGans (Gamsberg Mountains).

- Kaikhāben: lit. Great Rivals- North of ǃAutsawises (Berseba) on both banks of the ǁAub (Fish River).

- Tsoaxudaman: lit. Damaras of the Swakop River valley- Tsoaxaub is Khoekhoegowab for Swakop River. The Tsoaxudaman are also known as the Tsoaxaudaman.

- ǀGainîn: lit. The tough people – Between ǁGōbamǃnâs (Bullspoort/ Nauklift) and the southern ǃNamib (Namib) sand sea. Their name is derived from their ability to survive in such an environment. ǀGainîn can also be spelled as ǀGaiǁîn.

- ǀGaioaman: lit. Damaras that consume the wild cucumber- In the vicinity of the Parasis (Mountains). From Tsūob (Outjo) beyond of ǃHōb also known as Apabeb (Waterberg). They lived along the river ǁKūob (Omuramba Omatako).

- ǀGowanîn: lit. Damaras of the dunes (Kalahari Desert): Inhabited the entire ǀGowas also known as ǀŪmâs (Kalahari Desert) from ǀGaoǁnāǀaus commonly known as ǀAnes (Rehoboth), ǃHoaxaǃnâs (Hoachanas) and ǀGowabes commonly known as ǂKhoandawes (Gobabis). ǀGowanîn can also be spelled as ǀGowaǁîn.

- ǀHaiǀgâsedaman: lit. Damaras of Vaalgras- . The ǀHaiǀgâsedaman live in and around ǀHaiǀgâseb (Vaalgras), Tsēs (Tses) and ǃKhōb (Witrand- limestone terrace near Mukorob) in southern Namibia.

- ǀHūǃgaoben: lit. Named after the Kan nie dood tree endemic to the area)- The Khoekhoegowab name for the "Kan nie dood" tree is ǀHūs. They live in and around ǀGaoǁnāǀaus commonly known as ǀAnes (Rehoboth).

- ǀKhomanîn: lit. Damaras of the Khomas Hochland- The Khoekhoegowab name for the Khomas Hochland is ǀKhomas. To the east of the mountains of ǀGaoǁnāǀaus commonly known as ǀAnes (Rehoboth) and in and around Kaisabes commonly known as ǀAeǁgams (Windhoek). ǀKhomanîn can also be spelled as ǀKhomaǁîn, in 1854 were more than 40,000 in number.

- ǁHoanidaman: lit. Damaras of the Hoanib River- The Khoekhoegowab name of the Hoanib River is ǁHoanib. The ǁHoanidaman live along the length of the ǁHoanib (Hoanib River) and are also known as the Hoanidaman.

- ǁHuruben: lit. The people that grumble/mumble- Live in and around ǀUiǁaes (Twyfelfontein), between ǁHûab (Huab River) and ǃŪǂgâb (Ugab River). They are called ǁHuruben because they speakn a distinct dialect of Khoekhoegowab that sounds more like "grumbling/mumbling."

- ǁHûadaman: lit. Damaras of the Huab River- The Khoekhoegowab name of the Huab River is ǁHûab. The ǁHûadaman live along the length of the ǁHûab (Huab River).

- ǃAinîn: lit. Damaras of the planes- ǃAib in Khoekhoegowab means open fields or planes and the ǃAinîn were named after those environs. They live in the open fields to the south of ǀGaoǁnāǀaus commonly known as ǀAnes (Rehoboth). ǃAinîn can also be spelled as ǀAiǁîn.

- ǃAobeǁaen: lit. Feared nation/ People living on the periphery- They are found in and around ǃGuidiǁgams (Omaruru). This clan originally lived in the Khomas Hochland and were moved to ǃGuidiǁgams (Omaruru) thus were called ǃAobeǁaen (People living on the periphery i.e. people that are excluded) as they were moved without their consent.

- ǃGarinîn: lit. Damaras of the Orange River- The Khoekhoegowab name of the Orange River is ǃGarib. The ǃGarinîn are the southernmost Damara clan and live along the ǃGarib (Orange River). ǃGarinîn can also be spelled as ǃGariǁîn.

- ǃHâuǁnain: lit. Riem belt: Around the Orange and Molopo Rivers, South – Eastern Namibian Border. The ǃHâuǁnain lived in South Africa and were deported to Khōrixas (Khorixas). The ǃHâuǁnain are also known as ǃHâuǃgaen (Riemvasmakers).

- ǃKhuisedaman: lit. Damaras of the Kuiseb River- The Khoekhoegowab name for the Kuiseb River is ǃKhuiseb. The ǃKhuisedaman live along the length of the ǃKhuiseb (Kuiseb River), they are also founded at the mouth of this river that later developed into a settelemt ǃGommenǁgams (Walvis Bay).

- ǃNamidaman: lit. Damaras of the Namib Desert- The Khoekhoegowab name for the Namib Desert is ǃNamib. The ǃNamidaman lived primarily between ǃŪxab (Ugab River) and Huriǂnaub (Kunene River), they are also called Namidaman.

- ǃNaranîn: lit. ǃNara plant Damaras- It may be that the ǃNaranîn people mostly consumed the ǃNara plant or that the plants grew abundantly in their land. TheǃNaranîn live to the south-west of ǂGaios commonly known as ǃNaniǀaus (Sesfontein) in Gaogob (Kaokoveld). ǃNaranîn can also be spelled as ǃNaraǁîn.

- ǃNarenîn: lit. Freezing Damaras- Between ǃHanās (Kalkrand) and ǂNūǂgoaes (Keetmanshoop). The ǃNarenîn are named as such as a result of the cold temperatures experienced over this areas during the winter months. They have over the years intermingled with the Nama and are regarded as Namdaman. ǃNarenîn can also be spelled as ǃNareǁîn.

- ǃOeǂgân: lit. People who take shelter with sunset/ Mountain with curved slopes- In and around ǃOeǂgâb (Erongo Mountains), ǃŪsaǃkhōs (Usakos) and ǃAmaib (Ameib).

- ǃOmmen: lit. Muscular people- At ǃHōb also known as Apabeb (Waterberg), along ǂĒseb (Omaruru River) and between ǀÂǂgommes (Okombahe) and ǃOmmenǃgaus (Wilhelmstahl). The ǃOmmen were previously ǀGowanîn and were the original inhabitants of ǀÂǂgommes (Okombahe).

- ǂAodaman: lit. Damara living on the fringes- Between Gamaǂhâb (Kamanjab), Tsūob (Outjo) and Tsawiǀaus (Otavi). Primarily at Khōrixas (Khorixas) and to the east of ǂGaios commonly known as ǃNaniǀaus (Sesfontein) in Gaogob (Kaokoveld).

- ǂGaodaman: lit. Damaras of the ǂGaob River- In and around the ǂGaob River, which runs parallel with the ǃKhuiseb (Khuseb River) to the left and branch out into the ǃKhuiseb (Kuiseb River).

- ǂGawan: Insolent or audacious people: Between ǂĀǂams (Stampriet) and ǃGoregura-ābes commonly known as Khāxatsūs (Gibeon). This people have over the years intermingled with the local ǀKhowese (Witbooi) and surrounding Nama clans.

A separate group was created in the 1970s when Damara people living at Riemvasmaak in South Africa were expelled to Khorixas in the Damara bantustan in order to make space for a military installation. This group became known as the Riemvasmakers. They were given land by Damara King Justus ǁGaroëb to settle on. When in 1994 with the independence of South Africa a process of land restitution allowed the return of families and communities, some of the Riemvasmakers returned but a residual group founded their own traditional authority. They are seeking recognition from the Namibian government to be recognised as a separate Damara clan.[5][6]

Culture

The Damara are divided into clans, each headed by a chief, with a King, Justus ǁGaroëb, over the whole Damara people. Prince ǀHaihāb, Chief Xamseb, and ǁGuruseb were among the richest and most powerful chiefs.

Damara males were not circumcised. However, groups of boys were initiated into manhood through an elaborate hunting ritual. This ritual is repeated twice, for teenagers and grown men, after which the initiates are considered tribal elders.[7]

Their traditional clothing colors are green, white, and blue. Green and blue identify the different sub-groups. Some women may wear white and blue or white and green, the white representing peace and unity among all Damara-speaking people.

The women do household chores like cooking, cleaning, and gardening. Their primary duty is milking the cows in the morning and nurturing the young. Men traditionally hunt and herd the cattle, leaving the village as early as the sunrise, patrolling their area to protect their cattle and grazing ground as tradition dictates. Men can be very aggressive towards intruders if not notified of any other male presence in a grazing area.

Though many Damara people own and live on rural farms, the majority live in the small towns scattered across the Erongo region or in Namibia's capital city of Windhoek. Those that still live on farms tend to live in extended family groups of as many as one hundred, creating small villages of family members.

The Damara are rich in cattle and sheep. Some chiefs possess up to 8,000 head of horned cattle.

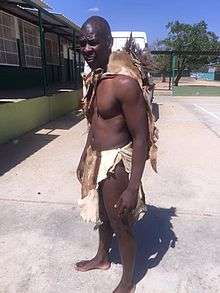

Historic traditional attire

The Damaran just like other African peoples made use of animal hides for clothing. The principal animal hides that were used were those of springbok and goats for clothing and sheep and jackal for blankets. Damaran traditional attires differentiated between a girl, an unmarried or married woman and an elderly woman in the same manner that it differentiated between boys, unmarried and married men and men of age. Some outfits were reserved for special ceremonies in contrast to everyday garments.

A girl in a Damara context is any female that has not yet undergone the menstrual cycle while a boy is any male that has not yet undergone the first hunting ritual. A hunting ritual was performed in the Damara culture as Damara males were not circumcised. The first hunting ritual was performed by boys in order to become man and the second by man to become community elders. All Damara children regardless of sex wore a ǃgaes, an apron like loin-cloth that covers genitalia. Girls would at a tender age undergo the ǂgaeǂnoas (have earring holes made) after which black thread would be inserted until such a time they will first start wearing ǃgamdi (earrings).

A man in the Damara context is any male that has undergone the first hunting ritual while a woman is any female that has experienced the menstrual cycle. The Damara culture would continue to differentiate between a married and unmarried man or woman. An unmarried man is called an axa-aob while a woman is an oaxaes. An unmarried man would simply wear a ǁnaweb which is a loin-cloth that is tucked in between the legs while an unmarried woman wore a ǃgaes to cover genitalia and a ǀgâubes to cover the rears.

A married man that has a child or children is called an aob, while a married woman with children is a taras. Such a man would wear a sorab which is a strip of soft leather worn between legs. Both ends are tucked under thong around waist and flapped over at front and the back. They would also wear a danakhōb which is the skin of any smallish animal that the wife presents to her husband at their wedding to wear on his head. The men would were the "head hide" to ceremonies and on auspicious occasions to show that he is the head of a household. The hide would preferably be of a ǃnoreb (a common genet). Married women just like girls would wear a ǀgâubes (rear loincloth) and would wear a ǀawiǃgaes (loincloth consisting of strips) instead of a regular ǃgaes. A ǁkhaikhōb would also be worn only to ceremonies and on auspicious occasions, but mostly during pregnancy and by elder women on a daily basis. The ǁkhaikhōb is the hide of a medium-sized antelope most preferably a ǀhauib (a Damara dik-dik) or a dôas, ǀnâus (Duiker) that is worn to cover breast and the abdomen (during pregnancy).

An elderly man, kaikhoeb, is any Damara male that has undergone the second and last hunting ritual. An elderly woman, a kaikhoes, is a female that has concluded her menstrual cycle. All elderly men and women would wear a ǃgūb, which is a skirt-like loin-cloth or traditional skirt for men and women. Elderly women would also wear a ǁkhaikhōb and sometimes a khōǃkhaib (headgear fashioned of soft hide).

Women being more aware of beautification would wear ǃgamdi (small traditional earrings made from iron and or copper) and wear necklaces made of ostrich egg shells known as a ǁnûib in Khoekhoegowab. Women wore ǃganudi (arm bangles) and ǃgoroǃkhuidi (ornamental anklets) they also originally made from iron and or copper later replaced by beads and or ostrich egg shells. An anklet made from moth larvae (ǀkhîs) was also worn but only during performances/dances along with a tussled apron known as a ǀhapis (for females) and or ǀhapib (for males)

ǃNau-i (traditional facial foundation) also played a significant part in Damara and the wider Khoekhoe cosmetics. Women would ǀīǃnâ (perfume) hides and blankets by stewing buchu on hot stones placed under a ǀīǃnâs (dome-shaped basket) after which they would boro themselves (smear red ochre on their faces) early in the morning. They would also sprinkle some sâ-i (buchu powder) on their hides and blankets with a ǃūro-ams (powder-puff made from a piece of hare fur used to pluck ǃūros (tortoise-shell container, carried by women for holding sâ-i) to power oneself.)

Man also wore arm bangles (ǃganugu) and ǃgoroǃkhuigu (anklets) which were unadorned in design and denser than those of women. A strand of beads that criss-crossed the chess known as a karab was also worn by men. Tsaob (ash) was used as an anti-perspiring agent by the Damaran as they believe that it is the purest substance on Earth.

Contemporary traditional attire

The replacement of animal hides with fabrics has also been visible in the Damara culture as the aforementioned outfits are mostly worn to cultural ceremonies and on auspicious occasions. Thus the Damaran sought for a perfect substitution for animal hides and introduced the Damarokoes (Damara dress.) The Damarokoes was adopted form missionary wives in the mid-19th century and was introduced due to the Christianisation of the Damaran as missionaries saw the animal hides as “primitive and exposing.” The dress adopted to cover up the “nude” Damara women ensured just that with its ankle-lengthiness and long sleeves and a ǃkhens (shawl) to ensure maximum coverage.

The Damaǃkhaib (headgear) is a unique innovation of the Damara women as they shaped a headgear that can be fashionable yet work effective as they still could ǂkhao (carry/load something on head) water containers and firewood. It is not only the ǃkhaib that was fashionable and work effective but also the sleeves as the sleeves have a protruding elbow design allowing the elbow to contract and release without constrains. The length of the dress is also fashionable and work effective as it is not too long so as to be caught by tweaks, branches and or thorns.

Damara man on the other hand were shirts, coats and or blazers with Damara colours being blue, white and green. Sometimes with a print or an embroidery.

References

- ↑ James Stuart Olson, « Damara » in The Peoples of Africa: An Ethnohistorical Dictionary, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, p. 137

- 1 2 "Damara Culture | Namibia Africa | Traditions, Heritage, Society & People". Namibiatourism.com.na. Retrieved 2013-09-02.

- ↑ Blench, Roger. 1999. "Are the African Pygmies an Ethnographic Fiction?" Archived January 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Pp 41–60 in Biesbrouck, Elders, & Rossel (eds.) Challenging Elusiveness: Central African Hunter-Gatherers in a Multidisciplinary Perspective. Leiden.

- 1 2 "African Death God. Supreme God of Life, Death and Seasonal Renewal". Godchecker – Your Guide to the Gods. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Jo Ractliffe. The Borderlands". www.stevenson.info. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Miyanicwe, Clemans (22 October 2014). "Riemvasmakers seek recognition". The Namibian.

- ↑ Barnard, Alan (1992) Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples Cambridge University Press pp 210–211