Demyansk Pocket

| Demyansk Pocket | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Walter von Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach | Pavel Kurochkin | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

100,000 (initial)[2][3] 31,000 replacement troops | 400,000 (initial) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

16th Army (10.01. - 31.05.1942): 11,777 KIA and 2,739 MIA 40,000 WIA Total: 55,000[4] |

Northwestern Front (07.01. - 20.05.1942): 88,908 KIA and MIA 156,603 WIA Total: 245,500[5] | ||||||

The Demyansk Pocket (German: Festung Demjansk or Kessel von Demjansk; Russian: Демя́нский котёл) was the name given to the pocket of German troops encircled by the Red Army around Demyansk (Demjansk), south of Leningrad, during World War II on the Eastern Front. The pocket existed mainly from 8 February to 21 April 1942. A much smaller force was surrounded in the Kholm Pocket at the town of Kholm, about 100 km (62 mi) to the southwest. Both resulted from the German retreat following their defeat during the Battle of Moscow.

The successful defence of Demyansk, achieved through the use of an airbridge, was a significant development in modern warfare. Its success was a major contributor to the decision by the Wehrmacht command to try the same tactic during the Battle of Stalingrad.

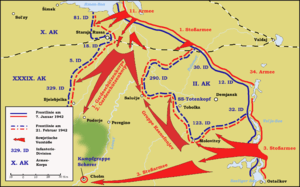

Encirclement

The encirclement began as the Demyansk Offensive Operation, the first phase being carried out from 7 January-20 May 1942 on the initiative of General Lieutenant Pavel Kurochkin, commander of Northwestern Front. The intention was to sever the link between the German Demyansk positions, and the Staraya Russa railway that formed the lines of communication of the German 16th Army. However, owing to the very difficult wooded and swampy terrain, and heavy snow cover, the initial advance by the Front was very modest against stubborn opposition.

On 8 January, a new offensive called the Rzhev–Vyazma Strategic Offensive Operation started. This incorporated the previous Front's planning into the Toropets–Kholm Offensive Operation between 9 January and 6 February 1942 which formed the southern pincer of the attack that, beginning the second phase of the northern pincer Demyansk Offensive Operation between 7 January and 20 May, which encircled the German 16th Army's (Generaloberst Ernst Busch) II Army Corps, and parts of the X Army Corps (General der Artillerie Christian Hansen) during winter 1941/1942.

Trapped in the pocket were the 12th, 30th, 32nd, 123rd and 290th infantry divisions, and the SS Division Totenkopf, as well as RAD, Police, Organisation Todt and other auxiliary units, for a total of about 90,000 German troops and around 10,000 auxiliaries. Their commander was General der Infanterie Walter Graf von Brockdorff-Ahlefeldt, commander of the II Army Corps.

Northwestern Front offensives

7 January–21 February 1942.

The intent of the Northwestern Front offensive was to encircle the entire northern flank of the 16th Army's forces, of which the 2nd Army Corps was only a small part, and the Soviet command was desperate to keep the Front moving even after this success. The first thrust was made by the 11th Army, 1st Shock Army and the 1st and 2nd Guards Rifle Corps released for the operation from Stavka reserve. A second thrust was executed on 12 February by the 3rd and 4th Shock Armies of the Kalinin Front, with the additional plan of directly attacking the encircled German forces by inserting two airborne brigades to support the advance of the 34th Army.[6] The front soon settled as the Soviet offensive petered out due to difficult terrain and bad weather.

After being assured that the pocket could be supplied with its daily requirement of 300 short tons (270 t) of supplies[2] by Luftflotte 1, Hitler ordered that the surrounded divisions hold their positions until relieved. The pocket contained two viable airfields at Demyansk and Peski capable of receiving transport aircraft. From the middle of February, the weather improved significantly, and while there was still considerable snow on the ground at this time, resupply operations were generally very successful due to inactivity of the VVS in the area.[2] However the operation did use up all of Luftflotte 1's transport capability, as well as elements of its bomber force.

Over the winter and spring, the Northwestern Front launched a number of attacks on the "Ramushevo corridor" that formed the tenuous link between Demyansk and Staraya Russa but was unable to reduce the pocket.

Breakout

On 21 March 1942, German forces under the command of Generalleutnant Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach attempted to manoevre through the "Ramushevo corridor". Soviet resistance on the Lovat River delayed II Corps' attack until April 14. Over the next several weeks, this corridor was widened. A battle group was able to break the siege on 22 April, but the fighting had taken a heavy toll.[7] Out of the approximately 100,000 men trapped, there were 3,335 lost and over 10,000 wounded.

Between the forming of the pocket in early February to the abandonment of Demyansk in May, the two pockets (including Kholm) received 65,000 short tons (59,000 t) of supplies (both through ground and aerial delivery), 31,000 replacement troops, and 36,000 wounded were evacuated. The supplies were delivered through over 100 flights of whitewashed Junkers Ju 52 transport aircraft per day.[3] However, the cost was significant. The Luftwaffe lost 265 aircraft, including 106 Junkers Ju 52, 17 Heinkel He 111 and two Junkers Ju 86 aircraft. In addition, 387 airmen were lost.[8] Richard Overy argues that the Demyansk airlift was a Pyrrhic victory, citing the loss of over 200 aircraft and their crew "when annual production of transports was running at only 500; and all to save 90,000 German soldiers, 64,000 of whom were either killed, wounded or too sick for service" by the airlift's end.[9]

Fighting in the area continued until 28 February 1943. The Soviets did not liberate Demyansk until 1 March 1943, with the retreat of the German troops.

The success of the Luftwaffe convinced Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Hitler that they could conduct effective airlift operations on the Eastern front.[8] Furthermore, it "determined Hitler in his belief that encircled troops should automatically hold on" to their territory.[10] After the German 6th Army was encircled in the Battle of Stalingrad, Göring convinced Hitler to resupply the besieged forces by Luftwaffe airlift until a relief effort could reach them;[11] however, the sheer scale of the effort required in Stalingrad (calculated at 750 tons per day) greatly exceeded the Luftwaffe's now-depleted capacities.[12] The Stalingrad airlift effort ultimately failed to deliver sufficient supplies, and the Germans estimated that they lost 488 transports, as well as 1,000 personnel, to the now-strengthened Soviet Air Forces.[13] Despite the Stalingrad airlift, the Germans suffered a devastating defeat nonetheless.

Citations

- ↑ Glantz 2001, p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Hayward 1997, p. 24.

- 1 2 Beevor 1999, p. 43.

- ↑ http://ww2stats.com/cas_ger_okh_dec42.html

- ↑ http://lib.ru/MEMUARY/1939-1945/KRIWOSHEEW/poteri.txt

- ↑ Rutherford 2008, p. 359.

- ↑ Rutherford 2008, p. 365.

- 1 2 Bergstrom 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Overy 1980, p. 414.

- ↑ Beevor 1999, pp. 43-44.

- ↑ Beevor 2012, p. 286.

- ↑ Hayward 1997, pp. 24-26.

- ↑ Beevor 1999, pp. 292, 398.

Bibliography

- Beevor, Antony (1999). Stalingrad. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140249859.

- Beevor, Antony (2012). The Second World War. New York: Back Bay Books. ISBN 978-0-316-02374-0.

- Bergstrom, Christer (2007). Stalingrad: The Air Battle: 1942-January 1943. London: Chevron/Ian Allen. ISBN 978-1-85780-276-4.

- http://victory.mil.ru/lib/books/h/nwf/index.html Сборник. На Северо-Западном фронте — М.: «Наука», 1969 (Вторая Мировая война в исследованиях, воспоминаниях, документах) Институт военной истории Министерства Обороны СССР; под редакцией и с предисловием члена-корреспондента АН СССР генерал-лейтенанта П. А. Жилина; cоставил и подготовил сборник кандидат военных наук, доцент, полковник Ф. Н. Утенков; научно-техническая работа проведена подполковником В. С. Кислинским.

- Glantz, David (October 1992). "The Ghosts of Demiansk: In Memory of the Soldiers of the Soviet 1st Airborne Corps". Journal of Military History. 56 (4): 617–650. doi:10.2307/1986164. JSTOR 1986164.

- Glantz, David (2001). "The Soviet-German War 1941-1945: Myths and Realities: A Survey Essay". Strom Thurmond Institute. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Group of authors, A collection. On the North-Western Front, Moscow, Science (pub.), 1969 (Second World War in research, memoirs, documents), Institute of military history of Ministry of Defence of USSR, edited and with forward by member-correspondent AN SSR, General-lieutenant P.A. Zhilin; compiled and prepared for publication by candidate of military sciences, dozent, Colonel F.N. Utenkov, scientific-technical work undertaken by Sub-colonel V.S. Kislinsky.

- Hayward, Joel (Spring 1997). "Stalingrad: An Examination of Hitler's Decision to Airlift" (PDF). Airpower Journal. 11 (1): 21–37.

- Overy, Richard (July 1980). "Hitler and Air Strategy". Journal of Contemporary History. 15 (3): 405–421. JSTOR 260411.

- Rutherford, Jeff (2008). "Life and Death in the Demiansk Pocket: The 123rd Infantry Division in Combat and Occupation". Central European History. 41 (3). doi:10.1017/S0008938908000551. JSTOR 20457366.

Further reading

- Forczyk, Robert (2012). Demyansk 1942-43; The frozen fortress. Osprey Campaign Series #245. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1849085526

Coordinates: 57°39′00″N 32°28′00″E / 57.6500°N 32.4667°E