Diatomaceous earth

Diatomaceous earth (pronunciation: /ˌdaɪ.ətəˌmeɪʃəs ˈɜːrθ/), also known as D.E., diatomite, or kieselgur/kieselguhr, is a naturally occurring, soft, siliceous sedimentary rock that is easily crumbled into a fine white to off-white powder. It has a particle size ranging from less than 3 micrometres to more than 1 millimetre, but typically 10 to 200 micrometres. Depending on the granularity, this powder can have an abrasive feel, similar to pumice powder, and has a low density as a result of its high porosity. The typical chemical composition of oven-dried diatomaceous earth is 80 to 90% silica, with 2 to 4% alumina (attributed mostly to clay minerals) and 0.5 to 2% iron oxide.[1]

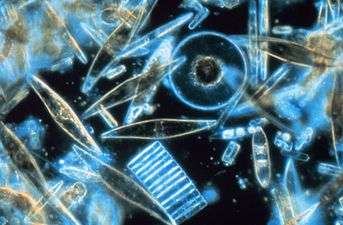

Diatomaceous earth consists of fossilized remains of diatoms, a type of hard-shelled algae. It is used as a filtration aid, mild abrasive in products including metal polishes and toothpaste, mechanical insecticide, absorbent for liquids, matting agent for coatings, reinforcing filler in plastics and rubber, anti-block in plastic films, porous support for chemical catalysts, cat litter, activator in blood clotting studies, a stabilizing component of dynamite, and a thermal insulator.

Geology and occurrence

Composition

Each deposit of diatomaceous earth is different, with varying blends of pure diatomaceous earth combined with other natural clays and minerals. The diatoms in each deposit contain different amounts of silica, depending on the age of the deposit. The species of diatom may also differ among deposits. The species of diatom is dependent upon the age and paleo-environment of the deposit. In turn, the shape of a diatom is determined by its species.

Many deposits throughout British Columbia, Canada, such as Red Lake Earth, are from the Miocene age and contain a species of diatom known as Melosira granulata. These diatoms are approximately 12 to 13 million years old and have a small globular shape. A deposit containing diatoms from this age can provide many more benefits than that of an older deposit. For example, diatoms from the Eocene age (approximately 40 to 50 million years old) are not as effective in their ability to absorb fluids because older diatoms recrystallize, their small pores becoming filled with silica.[2]

Formation

Diatomite forms by the accumulation of the amorphous silica (opal, SiO2·nH2O) remains of dead diatoms (microscopic single-celled algae) in lacustrine or marine sediments. The fossil remains consist of a pair of symmetrical shells or frustules.[1]

Discovery

In 1836 or 1837, the peasant and goods waggoner Peter Kasten discovered diatomaceous earth (German: Kieselgur) when sinking a well on the northern slopes of the Haußelberg hill, in the Lüneburg Heath in north Germany. Initially, it was thought that limestone had been found, which could be used as fertilizer.

Extraction and storage sites in the Lüneburg Heath

- Neuohe – extraction from 1863 to 1994

- Wiechel from 1871 to 1978

- Hützel from 1876 to 1969

- Hösseringen from ca. 1880 to 1894

- Hammerstorf from ca. 1880 to 1920

- Oberohe from 1884 to 1970

- Schmarbeck from 1896 to ca. 1925

- Steinbeck from 1897 to 1928

- Breloh from 1907 to 1975

- Schwindebeck from 1913 to 1973

- Hetendorf from 1970 to 1994

The deposits are up to 28 metres (92 ft) thick and are all of freshwater diatomaceous earth.

ca. 1900–1910 Diatomaceous earth pit at Neuohe

ca. 1900–1910 Diatomaceous earth pit at Neuohe ca. 1900–1910 a drying area: one firing pile is being prepared; another is under way

ca. 1900–1910 a drying area: one firing pile is being prepared; another is under way 1913 Staff at the Neuohe factory, with workers and a female cook in front of a drying shed

1913 Staff at the Neuohe factory, with workers and a female cook in front of a drying shed

Until the First World War almost the entire worldwide production of diatomaceous earth was from this region.

Other deposits

In Germany, diatomaceous earth was also extracted at Altenschlirf[3] on the Vogelsberg (Upper Hesse) and at Klieken[4] (Saxony-Anhalt).

There is a layer of diatomaceous earth up to 4 metres (13 ft) thick in the nature reserve of Soos in the Czech Republic.

Deposits on the isle of Skye, off the west coast of Scotland, were mined until 1960.[5]

In Colorado and in Clark County, Nevada, United States, there are deposits that are up to several hundred metres thick in places. Marine deposits have been worked in the Sisquoc Formation in Santa Barbara County, California near Lompoc and along the Southern California coast. Additional marine deposits have been worked in Maryland, Virginia, Algeria and the MoClay of Denmark. Freshwater lake deposits occur in Nevada, Oregon, Washington and California. Lake deposits also occur in interglacial lakes in the eastern United States, in Canada and in Europe in Germany, France, Denmark and the Czech Republic. The worldwide association of diatomite deposits and volcanic deposits suggests that the availability of silica from volcanic ash may be necessary for thick diatomite deposits.[6]

Sometimes diatomaceous earth is found on the surfaces of deserts. Research has shown that the erosion of diatomaceous earth in such areas (such as the Bodélé Depression in the Sahara) is one of the most important sources of climate-affecting dust in the atmosphere.

The siliceous frustules of diatoms accumulate in fresh and brackish wetlands and lakes. Some peats and mucks contain a sufficient abundance of frustules that they can be mined. Most of Florida’s diatomaceous earths have been found in the muck of wetlands or lakes. The American Diatomite Corporation, from 1935 to 1946, refined a maximum of 145 tons per year from their processing plant near Clermont, Florida. Muck from several locations in Lake County, Florida was dried and burned (calcined) to produce the diatomaceous earth.[7]

The commercial deposits of diatomite are restricted to Tertiary or Quaternary periods. Older deposits from as early as the Cretaceous Period are known, but are of low quality.[6]

Applications

Diatomaceous earth is available commercially in several formats:

- granulated diatomaceous earth is a raw material simply crushed for convenient packaging

- milled or micronized diatomaceous earth is especially fine (10 µm to 50 µm) and used for insecticides.

- calcined diatomaceous earth is heat-treated and activated for filters.

Explosives

In 1866, Alfred Nobel discovered that nitroglycerin could be made much more stable if absorbed in diatomite. This allows much safer transport and handling than nitroglycerin in its raw form. He patented this mixture as dynamite in 1867; the mixture is also called guhr dynamite.

Filtration

The Celle engineer Wilhelm Berkefeld recognized the ability of diatomaceous earth to filter, and he developed tubular filters (known as filter candles) fired from diatomaceous earth.[8] During the cholera epidemic in Hamburg in 1892, these Berkefeld filters were used successfully. One form of diatomaceous earth is used as a filter medium, especially for swimming pools. It has a high porosity because it is composed of microscopically small, hollow particles. Diatomaceous earth (sometimes referred to by trademarked brand names such as Celite) is used in chemistry as a filtration aid, to filter very fine particles that would otherwise pass through or clog filter paper. It is also used to filter water, particularly in the drinking water treatment process and in fish tanks, and other liquids, such as beer and wine. It can also filter syrups, sugar, and honey without removing or altering their color, taste, or nutritional properties.[9]

Abrasive

The oldest use of diatomite is as a very mild abrasive and, for this purpose, it has been used both in toothpaste and in metal polishes, as well as in some facial scrubs.

Pest control

Diatomite is used as an insecticide, due to its abrasive and physico-sorptive properties.[10] The fine powder absorbs lipids from the waxy outer layer of insects' exoskeletons, causing them to dehydrate. Arthropods die as a result of the water pressure deficiency, based on Fick's law of diffusion. This also works against gastropods and is commonly employed in gardening to defeat slugs. However, since slugs inhabit humid environments, efficacy is very low. It is sometimes mixed with an attractant or other additives to increase its effectiveness. The shape of the diatoms contained in a deposit has not been proven to affect their functionality when it comes to the absorption of liquids; however, certain applications, such as that for slugs and snails, do work best when a particular shaped diatom is used. For example, in the case of slugs and snails large, spiny diatoms work best to lacerate the epithelium of the mollusk. Diatom shells will work to some degree on the vast majority of animals that undergo ecdysis in shedding cuticle, such as arthropods or nematodes. It may have some effect also on lophotrochozoans, such as mollusks or annelids.

Medical-grade diatomite has been studied for its efficacy as a deworming agent in cattle; in both studies cited the groups being treated with diatomaceous earth did not fare any better than control groups.[11][12] It is commonly used in lieu of boric acid, and can be used to help control and possibly eliminate bed bug, house dust mite, cockroach, ant and flea infestations.[13] This material has wide application for insect control in grain storage.[14]

In order to be effective as an insecticide, diatomaceous earth must be uncalcinated (i.e., it must not be heat-treated prior to application)[15] and have a mean particle size below about 12 µm (i.e., food-grade – see below).

Although considered to be relatively low-risk, pesticides containing diatomaceous earth are not exempt from regulation in the United States under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act and must be registered with the Environmental Protection Agency.[16]

Thermal

Its thermal properties enable it to be used as the barrier material in some fire resistant safes. It is also used in evacuated powder insulation for use with cryogenics.[17] Diatomaceous earth powder is inserted into the vacuum space to aid in the effectiveness of vacuum insulation. It was used in the Classical AGA Cookers as a thermal heat barrier.

Catalyst support

Diatomaceous earth also finds some use as a support for catalysts, generally serving to maximize a catalyst's surface area and activity. For example, nickel, referred to as Ni–Kieselguhr, can be supported on the material to improve its activity as a hydrogenation catalyst.[18]

Use in agriculture

Natural freshwater diatomaceous earth is used in agriculture for grain storage as an anticaking agent, as well as an insecticide.[19] It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a feed additive[20] to prevent caking.

Some believe it may be used as a natural anthelmintic (dewormer), although studies have not shown it to be effective.[11][12] Some farmers add it to their livestock and poultry feed to prevent the caking of feed.[21] "Food Grade Diatomaceous Earth" is widely available in agricultural feed supply stores.

Hydroponics

Freshwater diatomite can be used as a growing medium in hydroponic gardens.

It is also used as a growing medium in potted plants, particularly as bonsai soil. Bonsai enthusiasts use it as a soil additive, or pot a bonsai tree in 100% diatomaceous earth. Like perlite, vermiculite, and expanded clay, it retains water and nutrients, while draining fast and freely, allowing high oxygen circulation within the growing medium.

Marker in livestock nutrition experiments

Natural dried, not calcined diatomaceous earth is regularly used in livestock nutrition research as a source of acid insoluble ash (AIA), which is used as an indigestible marker. By measuring the content of AIA relative to nutrients in test diets and feces or digesta sampled from the terminal ileum (last third of the small intestine) the percentage of that nutrient digested can be calculated using the following equation:

- Where:

- N is the nutrient digestibility (%)

- Nf is the amount of nutrients in the feces (%)

- NF is the amount of nutrients in the feed (%)

- Af is the amount of AIA in the feces (%)

- AF is the amount of AIA in the feed (%)

Natural freshwater diatomaceous earth is preferred by many researchers over chromic oxide, which has been widely used for the same purpose, the latter being a known carcinogen and, therefore, a potential hazard to research personnel.

Construction

Spent diatomaceous from the brewing process can be added to ceramic mass for the production of red bricks with higher open porosity.[22]

Specific varieties

- Tripolite is the variety found in Tripoli, Libya.

- Bann clay is the variety found in the Lower Bann valley in Northern Ireland.

- Moler (Mo-clay) is the variety found in northwestern Denmark, especially on the islands of Fur and Mors.

- Freshwater-derived food grade diatomaceous earth is the type used in United States agriculture for grain storage, as feed supplement, and as an insecticide. It is produced uncalcinated, has a very fine particle size, and is very low in crystal silica (<2%).

- Salt-water-derived pool/ beer/ wine filter grade is not suitable for human consumption or effective as an insecticide. Usually calcinated before being sold to remove impurities and undesirable volatile contents, it is composed of larger particles than the freshwater version and has a high crystalline silica content (>60%).

Microbial degradation

Certain species of bacteria in oceans and lakes can accelerate the rate of dissolution of silica in dead and living diatoms; by using hydrolytic enzymes to break down the organic algal material.[23][24]

Climatologic importance

The Earth's climate is affected by dust in the atmosphere, so locating major sources of atmospheric dust is important for climatology. Recent research indicates that surface deposits of diatomaceous earth play an important role. For instance, the largest single atmospheric dust source is the Bodélé depression in Chad, where storms push diatomite gravel over dunes, generating dust by abrasion.[25]

Safety considerations

Inhalation of crystalline silica is harmful to the lungs, causing silicosis. Amorphous silica is considered to have low toxicity, but prolonged inhalation causes changes to the lungs.[26] Diatomaceous earth is mostly amorphous silica, but contains some crystalline silica, especially in the saltwater forms.[27] In a study of workers, those exposed to natural D.E. for over 5 years had no significant lung changes, while 40% of those exposed to the calcined form had developed pneumoconiosis.[28] Today's common D.E. formulations are safer to use as they are predominantly made up of amorphous silica and contain little or no crystalline silica.[29]

The crystalline silica content of D.E. is regulated in the United States by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and there are guidelines from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health setting maximum amounts allowable in the product (1%) and in the air near the breathing zone of workers, with a recommended exposure limit at 6 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday.[29] OSHA has set a permissible exposure limit for diatomaceous earth as 20 mppcf (80 mg/m3/%SiO2). At levels of 3000 mg/m3, diatomaceous earth is immediately dangerous to life and health.[30]

In the 1930s, long-term occupational exposure among workers in the cristobalite D.E. industry who were exposed to high levels of airborne crystalline silica over decades were found to have an increased risk of silicosis.[31]

Today, workers are required to use respiratory-protection measures when concentrations of silica exceed allowable levels.

Diatomite produced for pool filters is treated with high heat (calcination) and a fluxing agent (soda ash), causing the formerly harmless amorphous silicon dioxide to assume its crystalline form.[29]

See also

- Biomineralization

- Diatom

- Frustule

- Fuller's earth

- Perlite

- Rock flour

- Silica aerogel

- Siliceous ooze

- Zeolite

References

- 1 2 Antonides, Lloyd E. (1997). Diatomite (PDF). U.S.G.S. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Diatoms". UCL London's Global University. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ↑ http://www2.natpa.de/bonifatius/senken/p7.htm Über den früheren Abbau von Kieselgur im Vogelsberg/Hessen Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Geschichte des Kieselgurabbaus in Klieken Archived April 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.stornowaygazette.co.uk/what-s-on/leisure/skye-diatomite-a-lost-industry-1-118249

- 1 2 Cummins, Arthur B., Diatomite, in Industrial Minerals and Rocks, 3rd ed. 1960, American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers, pp. 303–319

- ↑ Davis, Jr., John H. (1946). The Peat Deposits of Florida Their Occurrence, Development and Uses, Geological Bulletin No. 30. Florida Geological Survey.

- ↑ ELGA Berkefeld Water Treatment History

- ↑ Root, A.I.; E.R. Root (March 1, 2005). "The ABC and xyz of bee culture". Kessinger Publishing: 387. ISBN 978-1-4326-2685-3. Retrieved March 8, 2011

- ↑ Fields, Paul; Allen, Sylvia; Korunic, Zlatko; McLaughlin, Alan; Stathers, Tanya (July 2002). "Standardized testing for diatomaceous earth" (PDF). Proceedings of the Eighth International Working Conference of Stored-Product Protection. York, U.K.: Entomological Society of Manitoba.

- 1 2 Lartigue, E. del C.; Rossanigo, C. E. (2004). "Insecticide and anthelmintic assessment of diatomaceous earth in cattle". Veterinaria Argentina. 21 (209): 660–674.

- 1 2 Fernandez, M. I.; Woodward, B. W.; Stromberg, B. E. (1998). "Effect of diatomaceous earth as an anthelmintic treatment on internal parasites and feedlot performance of beef steers". Animal Science. 66 (3): 635–641. doi:10.1017/S1357729800009206.

- ↑ Faulde, M. K.; Tisch, M.; Scharninghausen, J. J. (August 2006). "Efficacy of modified diatomaceous earth on different cockroach species (Orthoptera, Blattellidae) and silverfish (Thysanura, Lepismatidae)". Journal of Pest Science. 79 (3): 155–161. doi:10.1007/s10340-006-0127-8.

- ↑ "The Food Storage Faq – Specific Specifications". Survival-center.com. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Capinera, John L. (2008). "Diatomaceous earth". In Capinera, John L. Encyclopedia of Entomology (Second ed.). Springer. p. 1216. ISBN 9781402062421.

- ↑ "Pesticide Labeling Questions & Answers | Pesticide Labeling Consistency | US EPA". EPA. January 10, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ Flynn, Thomas M. "Cryogenic Equipment and Cryogenic Systems Analysis." Cryogenic Engineering. Boca Raton [etc.: CRC, 2005. Print.

- ↑ Nishimura, Shigeo (2001). Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation for Organic Synthesis (1st ed.). Newyork: Wiley-Interscience. pp. 2–5. ISBN 9780471396987.

- ↑ "Prevention and Management of Insects and Mites in Farm-Stored Grain". Province of Manitoba. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- ↑ "21 CFR 573.340 - Diatomaceous earth" (PDF). Code of Federal Regulations (annual edition)—Title 21 - Food and Drugs—Part 573 - Food additives permitted in feed and drinking water of animals—Section 573.340 - Diatomaceous earth. Food and Drug Administration/U.S. Government Publishing Office. 1 April 2001. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Diatomaceous Earth (DE)

- ↑ Ferraz; et al. (2011). "Manufacture of ceramic bricks using recycled brewing spent kieselguhr". Materials and Manufacturing Processes. 26 (10): 1319–1329. doi:10.1080/10426914.2011.551908.

- ↑ Kay D. Bidle; Farooq Azam (1999). "Accelerated dissolution of diatom silica by marine bacterial assemblages". Nature. 397: 508–512. doi:10.1038/17351.

- ↑ "The Structure of Microbial Community and Degradation of Diatoms in the Deep Near-Bottom Layer of Lake Baikal". 2013.

- ↑ Washington, R.; Todd, M. C.; Lizcano, G.; Tegen, I.; Flamant, C.; Koren, I.; Ginoux, P.; Engelstaedter, S.; Bristow, C. S.; Zender, C. S.; Goudie, A. S.; Warren, A.; Prospero, J. M. (2006). "Links between topography, wind, deflation, lakes and dust: The case of the Bodélé Depression, Chad". Geophysical Research Letters. 33 (9). Bibcode:2006GeoRL..33.9401W. doi:10.1029/2006GL025827. ISSN 0094-8276.

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pel88/68855-54.html

- ↑ http://www.spca.bc.ca/assets/documents/welfare/professional-resources/farmer-resources/diatomaceous-earth-factsheet.pdf

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/81-123/pdfs/0552.pdf

- 1 2 3 Inert Dusts at Kansas State University

- ↑ "CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards - Silica, amorphous". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ↑ Hughes, Janet M.; Weill, Hans; Checkoway, Harvey; Jones, Robert N.; Henry, Melanie M.; Heyer, Nicholas J.; Seixas, Noah S.; Demers, Paul A. (1998). "Radiographic Evidence of Silicosis Risk in the Diatomaceous Earth Industry". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 158 (3): 807–814. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9709103. ISSN 1073-449X.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0248

- CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Diatomite: Statistics and Information – USGS

- Tripolite: Tripolite mineral data Citat: "...A diatomaceous earth consisting of opaline silica..."

- DIATOMACEOUS EARTH: A Non Toxic Pesticide