Diplomatic immunity

Diplomatic immunity is a form of legal immunity that ensures diplomats are given safe passage and are considered not susceptible to lawsuit or prosecution under the host country's laws, although they can still be expelled. Modern diplomatic immunity was codified as international law in the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961) which has been ratified by all but a handful of nations, though the concept and custom of such immunity have a much longer history dating back thousands of years. Many principles of diplomatic immunity are now considered to be customary law. Diplomatic immunity as an institution developed to allow for the maintenance of government relations, including during periods of difficulties and armed conflict. When receiving diplomats, who formally represent the sovereign, the receiving head of state grants certain privileges and immunities to ensure they may effectively carry out their duties, on the understanding that these are provided on a reciprocal basis.

Originally, these privileges and immunities were granted on a bilateral, ad hoc basis, which led to misunderstandings and conflict, pressure on weaker states, and an inability for other states to judge which party was at fault. An international agreement known as the Vienna Conventions codified the rules and agreements, providing standards and privileges to all states.

It is possible for the official's home country to waive immunity; this tends to happen only when the individual has committed a serious crime, unconnected with their diplomatic role (as opposed to, say, allegations of spying), or has witnessed such a crime. However, many countries refuse to waive immunity as a matter of course; individuals have no authority to waive their own immunity (except perhaps in cases of defection). Alternatively, the home country may prosecute the individual. If immunity is waived by a government so that a diplomat (or their family members) can be prosecuted, it must be because there is a case to answer and it is in the public interest to prosecute them. For instance, in 2002, a Colombian diplomat in London was prosecuted for manslaughter, once diplomatic immunity was waived by the Colombian government.[1][2]

History

Ancient times

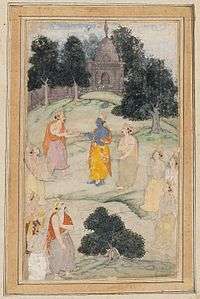

The concept of diplomatic immunity can be found in ancient Indian epics like Ramayana (between 3000 and 2000 BC) (traditional Hindu dating: over 100,000 years ago) and Mahabharata (around 4th century BC; traditional Hindu dating: 3000 BC), where messengers and diplomats were given immunity from capital punishment. In Ramayana, when the demon king Ravana ordered the killing of Hanuman, Ravana's younger brother Vibhishana pointed out that messengers or diplomats should not be killed or arrested, as per ancient practices.

During the evolution of international justice, many wars were considered rebellions or unlawful by one or more combatant sides. In such cases, the servants of the "criminal" sovereign were often considered accomplices and their persons violated. In other circumstances, harbingers of inconsiderable demands were killed as a declaration of war. Herodotus records that when heralds of the Persian king Xerxes demanded "earth and water" (i.e., symbols of submission) of Greek cities, the Athenians threw them into a pit and the Spartans threw them down a well for the purpose of suggesting they would find both earth and water at the bottom, these often being mentioned by the messenger as a threat of siege. However, even for Herodotus, this maltreatment of envoys is a crime, and he immediately recounts a story of divine vengeance befalling Sparta for this deed.[3]

A Roman envoy was urinated on as he was leaving the city of Tarentum. The oath of the envoy, "This stain will be washed away with blood!", was fulfilled during the Second Punic War. The arrest and ill-treatment of the envoy of Raja Raja Chola by the king of Kulasekhara dynasty (Second Cheras), which is now part of modern India, led to the naval Kandalur War in AD 994.

Pope Gelasius I was the first pope recorded as enjoying diplomatic immunity, as it is noted in his letter Duo sunt to emperor Anastasius.[4]

As diplomats by definition enter the country under safe-conduct, violating them is normally viewed as a great breach of honour, although there have been numerous cases in which diplomats have been killed. Genghis Khan and the Mongols were well known for strongly insisting on the rights of diplomats, and they would often take terrifying vengeance against any state that violated these rights. The Mongols would often raze entire cities in retaliation for the execution of their ambassadors, and invaded and destroyed the Khwarezmid Empire after their ambassadors had been mistreated.[5]

The beginnings of modern immunity

The British Parliament first guaranteed diplomatic immunity to foreign ambassadors in 1709, after Count Andrey Matveyev, a Russian resident in London, had been subjected to verbal and physical abuse by British bailiffs.

Modern diplomatic immunity evolved parallel to the development of modern diplomacy. In the 17th century, European diplomats realized that protection from prosecution was essential to doing their jobs, and a set of rules evolved guaranteeing the rights of diplomats. These were still confined to Western Europe and were closely tied to the prerogatives of nobility. Thus, an emissary to the Ottoman Empire could expect to be arrested and imprisoned upon the outbreak of hostilities between his state and the empire. The French Revolution also disrupted this system, as the revolutionary state and Napoleon imprisoned numerous diplomats who were accused of working against France. More recently, the Iran hostage crisis is universally considered a violation of diplomatic immunity. Although the hostage takers did not officially represent the state, host countries are obligated to protect diplomatic property and personnel. On the other hand, during World War II, diplomatic immunity was upheld and the embassies of the belligerents were evacuated through neutral countries.

For the upper class of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, diplomatic immunity was an easy concept to understand. The first embassies were not permanent establishments but actual visits by high-ranking representatives, often close relatives, of the sovereign or the sovereign in person. As permanent representations evolved, usually on a treaty basis between two powers, they were frequently staffed by relatives of the sovereign or high-ranking nobles.

Warfare was a status of hostilities not between individuals but between their sovereigns, and the officers and officials of European governments and armies often changed employers. Truces and ceasefires were commonplace, along with fraternization between officers of enemy armies during them. When prisoners, the officers usually gave their parole and were only restricted to a city away from the theatre of war. Almost always, they were given leave to carry their personal sidearms. Even during the French revolutionary wars, British scientists visited the French Academy. In such an atmosphere, it was easy to accept that some persons were immune to the laws. After all, they were still bound by strict requirements of honour and customs.

In the 19th century, the Congress of Vienna reasserted the rights of diplomats; and they have been largely respected since then, as the European model has spread throughout the world. Currently, diplomatic relations, including diplomatic immunity, are governed internationally by the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, which has been ratified by almost every country in the world.

In modern times, diplomatic immunity continues to provide a means, albeit imperfect, to safeguard diplomatic personnel from any animosity that might arise between nations. As one article put it: "So why do we agree to a system in which we're dependent on a foreign country's whim before we can prosecute a criminal inside our own borders? The practical answer is: because we depend on other countries to honor our own diplomats' immunity just as scrupulously as we honor theirs."[6]

In the United States, the Diplomatic Relations Act of 1978 (22 U.S.C. § 254a et seq.) follows the principles introduced by the Vienna Conventions. The United States tends to be generous when granting diplomatic immunity to visiting diplomats, because a large number of U.S. diplomats work in host countries less protective of individual rights. If the United States were to punish a visiting diplomat without sufficient grounds, U.S. representatives in other countries could receive harsher treatment. If a person with immunity is alleged to have committed a crime or faces a civil lawsuit, the State Department asks the home country to waive immunity of the alleged offender so that the complaint can be moved to the courts. If immunity is not waived, prosecution cannot be undertaken. However, the State Department still has the right to expel the diplomat. In many such cases, the diplomat's visas are canceled, and he and his family may be barred from returning to the United States. Crimes committed by members of a diplomat's family can also result in dismissal.[7]

Exceptions to the Vienna Convention

Some countries have made reservations to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, but they are minor. A number of countries limit the diplomatic immunity of persons who are citizens of the receiving country. As nations keep faith to their treaties with differing zeal, other rules may also apply, though in most cases this summary is a reasonably accurate approximation.[8] The Convention does not cover the personnel of international organizations, whose privileges are decided upon on a case-by-case basis, usually in the treaties founding such organizations. The United Nations system (including its agencies, which comprise the most recognizable international bodies such as the World Bank and many others) has a relatively standardized form of limited immunities for staff traveling on U.N. laissez-passer; diplomatic immunity is often granted to the highest-ranking officials of these agencies. Consular officials (that do not have concurrent diplomatic accreditation) formally have a more limited form of immunity, generally limited to their official duties. Diplomatic technical and administrative staff also have more limited immunity under the Vienna Convention; for this reason, some countries may accredit technical and administrative staff as attaché.

Other categories of government officials that may travel frequently to other countries may not have diplomatic passports or diplomatic immunity, such as members of the military, high-ranking government officials, ministers, and others. Many countries provide non-diplomatic official passports to such personnel, and there may be different classes of such travel documents such as official passports, service passports, and others. De facto recognition of some form of immunity may be conveyed by states accepting officials traveling on such documents, or there may exist bilateral agreements to govern such cases (as in, for example, the case of military personnel conducting or observing exercises on the territory of the receiving country).

Formally, diplomatic immunity may be limited to officials accredited to a host country, or traveling to or from their host country. In practice, many countries may effectively recognize diplomatic immunity for those traveling on diplomatic passports, with admittance to the country constituting acceptance of the diplomatic status.

Uses and abuses of diplomatic immunity

In reality, most diplomats are representatives of nations with a tradition of professional civil service, and are expected to obey regulations governing their behaviour and they suffer strict internal consequences (disciplinary action) if they flout local laws. In many nations, a professional diplomat's career may be compromised if they (or members of their family) disobey the local authorities or cause serious embarrassment, and such cases are, at any rate, a violation of the spirit of the Vienna Conventions.

The Vienna Convention is explicit that "without prejudice to their privileges and immunities, it is the duty of all persons enjoying such privileges and immunities to respect the laws and regulations of the receiving State." Nevertheless, on some occasions, diplomatic immunity leads to some unfortunate results; protected diplomats have violated laws (including those that would be violations at home as well) of the host country and that country has been essentially limited to informing the diplomat's nation that the diplomat is no longer welcome (persona non grata). Diplomatic agents are not, however, exempt from the jurisdiction of their home state, and hence prosecution may be undertaken by the sending state; for minor violations of the law, the sending state may impose administrative procedures specific to the foreign service or diplomatic mission.

Violation of the law by diplomats has included espionage, smuggling, child custody law violations, money laundering,[9] tax evasion, making terrorist threats,[10] slavery, preying on children over the Internet for sex,[11] and murder.

Offences against the person

On-duty police officer Yvonne Fletcher was murdered in London in 1984, by a person shooting from inside the Libyan embassy during a protest. The incident caused a breakdown in diplomatic relations until Libya admitted "general responsibility" in 1999.[12] The incident became a major factor in Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's decision to allow President of the United States Ronald Reagan to launch the U.S. bombing of Libya in 1986 from American bases in the United Kingdom.[13]

In 1987 in New York City, the Human Resources Administration placed 9-year-old Terrence Karamba in a foster home after his elementary school teachers noticed suspicious scars and injuries. He and his 7-year-old sister, who was also placed in City custody, told officials the wounds had been inflicted by their father, Floyd Karamba, an administrative attache at the Zimbabwean Mission to the U.N. No charges were filed, as Mr. Karamba had diplomatic immunity.[14]

On February 1999 in Vancouver, Canada, Kazuko Shimokoji, wife of the Japanese Consul-General, showed up at the ER of a city hospital with two black eyes and a bruised neck. She told doctors that her husband had beaten her. When local police questioned her husband, Mr. Shimokoji said, "Yes, I punched her out and she deserved it", and described the incident as "a cultural thing and not a big deal". Although an arrest warrant was issued, Mr. Shimokoji could not be arrested due to his diplomatic immunity. However, his statement to the police was widely reported in both the local and Japanese press. The subsequent public uproar prompted the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs to waive Mr. Shimokoji's immunity. Though he pleaded guilty in Canadian court, he was given an absolute discharge. Nonetheless, he was recalled to Japan where he was reassigned to office duty and had his pay cut.[15]

In November 2006 in New York City, Fred Matwanga, Kenyan diplomat to the U.N., was taken into police custody by officers responding to reports that he had assaulted his son; he was released after asserting diplomat immunity.[16][17]

In January 2011 in Lahore, Pakistan, American embassy employee Raymond Allen Davis shot and killed two Pakistani civilians, while a third man was struck and killed by a U.S. consulate car responding to the shooting. According to Davis, they were about to rob him and he acted in self-defense. When detained by police, Davis claimed to be a consultant at the U.S. consulate in Lahore. He was formally arrested and remanded into custody. Further investigations revealed that he was working with the CIA as a contractor in Pakistan. U.S. State Department declared him a diplomat and repeatedly requested immunity under the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, to which Pakistan is a signatory.[18][19] On March 16, 2011, Davis was released after the families of the two killed men were paid $2.4 million in diyya (a form of monetary compensation or blood money). Judges then acquitted him on all charges and Davis immediately departed Pakistan.[20]

In April 2012 in Manila, Panamanian diplomat Erick Bairnals Shcks was accused of raping a 19-year-old Filipino woman, but was later released from detention because Shcks "enjoys protection under the 1961 Vienna Convention".[21]

In March 2013, the Supreme Court of India restricted Italian ambassador Daniele Mancini from leaving India for breaching an undertaking given to the apex court.[22] Despite Italian and European Union protests regarding the restrictions as contrary to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, the Supreme Court of India said it would be unacceptable to argue diplomatic immunity after voluntarily subjecting to court's jurisdiction. The Italian envoy had invoked Article 32 of the Constitution of India when filing an affidavit to the Supreme Court taking responsibility for the return of the two Italian marines to India after casting their votes in the March 2012 general elections in Italy. The Indian Supreme Court opined that the Italian ambassador had waived his diplomatic immunity and could be charged for contempt. The two marines were being tried in India for the murder of two Indian fishermen off the coast of Kerala (see the 2012 Italian Navy Marines shooting incident in the Laccadive Sea).

In June 2014, the New Zealand government confirmed that Mohammed Rizalman Bin Ismail from Malaysia, aged in his 30s and employed at Malaysia's High Commission in Wellington, had invoked diplomatic immunity when faced with charges of burglary and assault with intent to rape after allegedly following a 21-year-old woman to her home.[23] He returned to Malaysia in May 2014 with his family while the case was still in hearing. The New Zealand foreign ministry was criticized for allowing the defendant to leave the country, which was blamed on miscommunication between the foreign ministries of the two countries, as Prime Minister John Key expressed his view that "the man should have faced the charges in New Zealand".[23] Malaysia eventually agreed to send the diplomat back to assist in investigations[24][25] and he was eventually tried and detained in New Zealand.[26]

In October 2013, Russian diplomat Dmitri Borodin was arrested in The Hague, The Netherlands, after neighbours called the police. Borodin was alleged to have been drunk and violent towards his children, aged two and four. Police were in the area because Borodin's wife had lost control over her car while also under influence, and had rammed four parked cars near the diplomats' house.[27] Russia immediately demanded an apology from the Dutch government for violating Borodin's diplomatic immunity. The row came at a time of tension between Russia and the Netherlands, after the Russian security services captured a Greenpeace vessel sailing under the Dutch flag, Arctic Sunrise, that was protesting against oil drilling in the Prirazlomnoye field.[28]

In August 2014, police were called to the Arlington, Virginia, home of an ambassador from Equatorial Guinea, where they transported a female victim (reportedly the ambassador's teenage daughter) who had been struck in the head. Police could not press assault charges because the suspect had diplomatic immunity.[29]

Drug smuggling

Diplomats and officials involved in drug smuggling have benefited from diplomatic immunity. For example, a Venezuelan general wanted in the United States on drugs charges and arrested in Aruba was released after the Venezuelan government protested his diplomatic immunity and threatened sanctions if Aruba did not release him.[30][31]

Cigarette smuggling

In December 2014, Gambian diplomats were found guilty by Southwark Crown Court of London for selling tax-free tobacco from the Gambian embassy in the United Kingdom. The Crown Prosecution Service told the court that much of this was sold from the embassy without paying VAT and excise duty.[32]

Employer abuse and slavery

Diplomatic immunity from local employment and labor law has precipitated incidents in which diplomatic staff have been accused of abusing local workers, who are often hired for positions requiring local knowledge (such as an administrative assistant, press/PR officer) or for general labor. In such situations, the employees are in a legal limbo where the laws of neither the host country nor the diplomat's country are enforceable. Diplomats have ignored local laws concerning minimum wages, maximum working hours, vacation and holidays, and in some cases have imprisoned employees in their homes, deprived them of their earned wages, passports, food, and communication with the outside world, abused them physically and emotionally, and invaded their privacy.[33][34] Reported incidents include the following:

- In 1999, a Bangladeshi woman, Shamela Begum, claimed she had been enslaved by a senior Bahraini envoy to the UN and his wife. Begum charged that the couple took her passport, struck her, and paid her just $800 for ten months of service — during which she was only twice allowed out of the couple's New York apartment. The envoy and his wife claimed diplomatic immunity, and Begum later reached a civil settlement with her employers. By some estimates, "hundreds of women have been exploited by their diplomat employers over the past 20 years."[11]

- In 2003 in Finland, a Filipino maid escaped from an embassy of an unidentified Asian country, and reported being held in conditions approaching slavery: she was forced to work from 7 am. to 10 pm., 7 days a week, and the ambassador's children were permitted to hit her. On grounds of diplomatic immunity, no charges could be filed.[35]

- In 2009, South Africa was criticised for claiming immunity from labor laws relating to a Ukrainian domestic worker at the residence of the South African ambassador in Ireland.[36]

- In 2010, the American Civil Liberties Union filed an amicus brief in Swarna v. Al-Awadi to argue that human trafficking is a commercial activity engaged in for personal profit, which falls outside the scope of a diplomat’s official functions, and therefore diplomatic immunity does not apply.[37] An appeals court ruled that Al-Awadi did not have diplomatic immunity in that situation.[38]

- In 2013, Indian consular official Devyani Khobragade was detained, hand-cuffed, strip searched, DNA swabbed, and held in a federal holding cell in New York, relating to allegations of non-payment of U.S. minimum wage and for fraudulently lying about the wages to be paid on a visa application for her domestic worker. India registered a strong protest and initiated a review of privileges afforded to American consular officials in India as a result.[39]

- In 2015, two Nepalese women were rescued from the fifth floor of Gurgaon residence of a Saudi Arabian diplomat in India. They were allegedly confined there and abused physically and sexually by the diplomat and his family and friends.[40] The women were rescued in a police raid planned after the police received a letter from the Nepal embassy regarding their plight. Several persons, the Saudi diplomat among them, were booked for wrongful confinement and gang rape. Saudi Ambassador Saud Mohammed Alsati commented, "This is completely false. We would not like to comment any further since the case is under investigation by the Indian police."[41] Ten days after the diplomat was accused, it was confirmed that he had left India.[42]

Vehicular offences

Parking violations

A particular problem is the difficulty in enforcing ordinary laws, such as prohibitions on double parking. For example, the Autobahn 555 in Cologne, Germany was nicknamed the "Diplomatenrennbahn" (Diplomatic Raceway), back when Bonn was the capital of West Germany, because of the numerous diplomats that used to speed through the highway under diplomatic immunity. Certain cities, e.g., The Hague, have taken to impounding such cars rather than fining their owners. Diplomats' status does not guarantee the release of impounded cars.

Diplomatic missions have their own regulations, but many require their staff to pay any fines due for parking violations. A 2006 economic study found that there was a significant correlation between home-country corruption (as measured by Transparency International) and unpaid parking fines: six countries had in excess of 100 violations per diplomat: Kuwait, Egypt, Chad, Sudan, Bulgaria and Mozambique.[43] In particular, New York City, the home of the United Nations Headquarters, regularly protests to the United States Department of State about non-payment of parking tickets because of diplomatic status. As of 2001, the city had more than 200,000 outstanding parking tickets from diplomats, totaling more than $21.3 million, of which only $160,682 had been collected.[44] In 1997, then-mayor Rudy Giuliani proposed to the Clinton administration that the U.S. State Department revoke the special DPL plates for diplomats who ignore parking summonses; the State Department denied Giuliani's request.[44]

In cities that impose a congestion charge, the decision of some diplomatic missions not to furnish payment has proved controversial. In London, embassies have amassed approximately £58 million in unpaid charges as of 2012, with the American embassy comprising approximately £6 million and the Russian, German and Japanese missions around £2 million each.[45][46]

Vehicular assault and drunk driving

In January 1997, Gueorgui Makharadze, a high-ranking Georgian diplomat, caused a five-car pileup in Washington, D. C., in the United States, which killed a 16-year-old girl. Makharadze's claim of diplomatic immunity created a national outrage in the United States, particularly given Makharadze's previous record of driving offenses: in April 1996, Makharadze had been charged with speeding in Virginia, and four months later, he was detained by District of Columbia police on suspicion of drunk driving.[47] In both prior cases, charges were dismissed based on his immunity. On the basis of the media coverage, Georgia revoked Makharadze's immunity, and he was ultimately sentenced to seven years in prison after pleading guilty to one count of involuntary manslaughter and four counts of aggravated assault.[48]

On 27 October 1998, in Vladivostok, Russia, Douglas Kent, the American Consul General to Russia, was involved in a car accident that left a young man, Alexander Kashin, disabled. Kent was not prosecuted in a U.S. court. Under the Vienna Convention, diplomatic immunity does not apply to civil actions relating to vehicular accidents, but in 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that, since he was using his vehicle for consular purposes, Kent could not be sued civilly.[49][50]

In 2001, a Russian diplomat, Andrei Knyazev, hit and killed a woman while driving drunk in Ottawa. Knyazev refused to take a breathalyzer at the scene of the crash, citing diplomatic immunity.[51] Russia refused Canadian requests to waive his immunity, and Knyazev was expelled from Canada. Though the Russian Foreign Ministry fired him and charged him with involuntary manslaughter, and Russian and Canadian authorities cooperated in the investigation, the case caused a political storm in Canada. Many accused the Foreign Ministry of incompetence after it emerged that Knyazev had twice been previously investigated for drunk driving. The Canadian Foreign Minister had fought unsuccessfully to have Knyazev tried in Ottawa.[52] In 2002, Knyazev was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter in Russia.[51]

On 3 December 2004, in Bucharest, Romania, Christopher Van Goethem, an American Marine serving his embassy, ran a red traffic signal, collided with a taxi, and killed popular Romanian musician Teo Peter.[53] Van Goethem's blood alcohol content was estimated at 0.09% from a breathalyser test, but he refused to give a blood sample for further testing and left for Germany before charges could be filed in Romania.[54] The Romanian government requested the American government to lift his immunity, which it refused to do. In a court-martial, he was acquitted of manslaughter and adultery (which is still a court martial offence) but was convicted of obstruction of justice and making false statements.[55]

On 9 December 2009, in Tanzania, Canadian Junior Envoy Jean Touchette was arrested after it was reported that he spat at a traffic police officer on duty in the middle of a traffic jam in the Banana district on the outskirts of Dar es Salaam. Canada's High Commissioner, Robert Orr, was summoned by the Tanzanian Foreign Ministry over the incident, and the junior envoy was later recalled.[56][57][58]

On 15 December 2009, in Singapore, the Romanian chargé d'affaires, Silviu Ionescu, was allegedly behind a drunk-driving hit-and-run accident that killed a 30-year-old man and seriously injured two others. He left Singapore for Romania three days after the accident.[59][60] The Romanian foreign ministry suspended Ionescu from his post.[61] A coroner's inquiry in Singapore, which included testimony by the Romanian embassy driver, concluded that Ionescu was solely responsible for the accident.[62] An Interpol Red Notice was subsequently issued for his arrest and possible extradition [63] notwithstanding the fact that Romania had not waived his diplomatic immunity and had commenced criminal proceedings against him in Romania.[64] The Singapore government argued that by reason of Article 39(2) of the Vienna Convention, Ionescu was no longer protected by diplomatic immunity.[65][66]

On 10 April 2011, in Islamabad, Pakistan, Patrick Kibuta, an electrical engineer in the United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan caused a vehicle collision with another vehicle, while under the influence of alcohol. Kibuta, who was driving in the opposing lane, injured a Canadian citizen residing in Islamabad, who suffered multiple fractures and required surgery. The Kohsar police impounded Mr. Kibuta's U.N. vehicle on the scene, and a blood test confirmed that he had an elevated blood alcohol level. Charges for reckless and drunken driving were filed against Kibuta, who enjoyed diplomatic immunity.[67][68]

In July 2013, Joshua Walde, an American diplomat in Nairobi, Kenya, crashed into a mini-bus, killing one man and seriously injuring eight others, who were left with no financial assistance to pay for hospital bills.[69] United States embassy officials took the diplomat and his family out of Kenya the following day.[69] The United States government was concerned about the impact the accident could have on bilateral relations with Kenya.[69] Walde gave a statement to police, but was not detained due to his diplomatic immunity.[69] Kenyan police say the case remains under investigation.[69]

On September 12, 2015, Sheikh Khalid bin Hamad Al Thani tried to claim diplomatic immunity when his Ferrari LaFerrari and a Porsche 911 GT3 were caught on camera drag racing through a residential neighborhood in Beverly Hills. He owns the cars and a drag racing team, and is a member of Qatar's ruling family. The Beverly Hills Police Department contacted the U.S. State Department to clarify if he had diplomatic immunity. They stated he did not. However, his face was not shown on camera, and no officer witnessed the crime, so the state of California has not yet pressed charges. He has since fled the country. The investigation is ongoing.[70][71]

On 14 February 2013, a vehicle bearing diplomatic plates registered to the US Embassy got into an accident in Islamabad, Pakistan involving two residents out of which one was killed and the other survived. Murder charges were laid under Section 320 of Pakistan Penal Code against the driver of the vehicle who is a diplomat according to Pakistani official.[72]

Financial abuse

Historically, the problem of large debts run up by diplomats has also caused many problems. Some financial institutions do not extend credit to diplomats because they have no legal means of ensuring the money be repaid. Local citizens and businesses are often at a disadvantage when filing civil claims against a diplomat, especially in cases of unpaid rent, alimony, and child support.

Rents

The bulk of diplomatic debt lies in the rental of office space and living quarters. Individual debts can range from a few thousand dollars to $1 million in back rent. A group of diplomats and the office space in which they work are referred to as a diplomatic mission. Creditors cannot sue missions individually to collect money they owe. Landlords and creditors have found that the only thing they can do is contact a city agency to see if they can try to get some money back. They cannot enter the offices or apartments of diplomats to evict them because the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act says that "the property in the United States of a foreign state shall be immune from attachment, arrest and execution" (28 U.S.C. § 1609). This has led creditors who are owed money by diplomats to become more cautious about their renters and to change their rental or payment policies.

In one case, for example, officials from Zaire stopped paying rent to their private landlord and ran up $400,000 in debt. When the landlord sued, the U.S. State Department defended the Zaireans on the basis of diplomatic immunity, and a circuit court agreed. When the landlord finally cut off the utilities, the officials fled without paying their back rent. The landlords reportedly later reached an "amicable agreement" with the Zaire government.[11]

Alimony and child support

The issue of abusing diplomatic immunity in family relations, especially alimony and child support, has become so widespread that it prompted discussion at the 1995 U.N. Fourth World Conference on Women, in Beijing. Historically, the United Nations has not become involved with family disputes and has refused to garnish the wages of diplomats who owe money for child support, citing Sovereign Immunity. However, in September 1995, the incumbent head of Legal Affairs for the United Nations acknowledged there was a moral and legal obligation to take at least a partial responsibility in family disputes. Fathers working as diplomats who refused to fulfil their family-related financial duties were increasing in numbers in the United Nations: several men who had left their wives and children were still claiming U.N. dependency, travel, and education allowances for their families, though they are no longer supporting those families.[73]

Taxes and fees

Diplomats are exempt from most taxes, but not from "charges levied for specific services rendered". In certain cases, whether a payment is or is not considered a tax may be disputed, such as central London's congestion charge. It was reported in 2006 that the UAE embassy had agreed to pay their own accumulated charges of nearly £100,000.[74]

There is an obligation for the receiving State not to "discriminate as between states"; in other words, any such fees should be payable by all accredited diplomats equally. This may allow the diplomatic corps to negotiate as a group with the authorities of the receiving country.

Diplomats are exempt from import duty and tariffs for items for their personal use. In some countries, this has led to charges that diplomatic agents are profiting personally from resale of "tax free" goods. The receiving state may choose to impose restrictions on what may reasonably constitute personal use (for example, only a certain quantity of cigarettes per day). When enacted, such restrictions are generally quite generous so as to avoid tit-for-tat responses.

Espionage

On 24 April 2008, in New Orleans, Mexican press attaché Rafael Quintero Curiel was seen stealing BlackBerry PDA units from a White House press meeting room. Quintero made it all the way to the airport before members of the United States Secret Service caught up with him. He initially denied taking the devices, but after being confronted with security video, Quintero claimed it was purely accidental, gave the devices back, claimed diplomatic immunity and left New Orleans with the Mexican delegation. He was eventually fired for the incident.[75]

Other incidents

In April 2010, a Qatari diplomat was arrested for having smoked in the toilet on a US-bound flight and having joked (upon questioning) that he was trying to light his shoe, a reference to the shoe-bomber Richard Reid. Two F-16 fighter jets had been scrambled to follow the airplane as a result.[76]

On 16 August 2012, it was alleged by the Ecuadorian embassy that the Government of the United Kingdom threatened to revoke the diplomatic status of the embassy of Ecuador in London in order to arrest Julian Assange.[77]

Diplomatic immunity in the United States

The following chart outlines the immunities afforded to foreign diplomatic personnel residing in the United States.[78] In general, these rules follow the Vienna Convention (or the New York Convention for UN officials) and apply in other countries as well (with the exceptions of immunities for United Nations officials, which can vary widely across countries based on the 'Host Country Agreement' signed between the UN and the host country, whereby additional immunities beyond those granted by the New York Convention may be established).

| Category | May be arrested or detained | Residence may be entered subject to ordinary procedures | May be issued traffic ticket | May be subpoenaed as witness | May be prosecuted | Official family member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplomatic | Diplomatic agent | No[lower-alpha 1] | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Member of administrative and technical staff | No[lower-alpha 1] | No | Yes | No | No | Same as sponsor | |

| Service staff | Yes[lower-alpha 2] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes[lower-alpha 2] | No[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Consular | Career consular officers | Yes, if for a felony and pursuant to a warrant.[lower-alpha 2] | Yes[lower-alpha 3] | Yes | No, for official acts. Testimony may not be compelled in any case. | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes[lower-alpha 4] | No[lower-alpha 2] |

| Honorary consular officers | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, for official acts. Yes, in all other cases | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes | No | |

| Consular employees | Yes[lower-alpha 2] | Yes | Yes | No, for official acts. Yes, in all other cases | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes[lower-alpha 2] | No[lower-alpha 2] | |

| International organization | Diplomatic-level staff of missions to international organizations | No[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 5] | No[lower-alpha 5] | Yes | No[lower-alpha 5] | No[lower-alpha 5] | Same as sponsor |

| International organization staff[lower-alpha 4] | Yes[lower-alpha 4] | Yes[lower-alpha 4] | Yes | No, for official acts. Yes, in all other cases | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes[lower-alpha 4] | No[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Support staff of missions to international organizations | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, for official acts. Yes, in all other cases | No, for official acts. Otherwise, yes | No | |

Notes and references

Notes

- 1 2 3 Reasonable constraints, however, may be applied in emergency circumstances involving self-defense, public safety, or the prevention of serious criminal acts.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 This table presents general rules. Particularly in the cases indicated, the employees of certain foreign countries may enjoy higher levels of privileges and immunities on the basis of special bilateral agreements.

- ↑ Note that consular residences are sometimes located within the official consular premises. In such cases, only the official office space is protected from police entry.

- 1 2 3 4 5 A small number of senior officers are entitled to be treated identically to "diplomatic agents".

- 1 2 3 4 If the international organisation is located in the country of the staff member's nationality, exemption only extends to official acts.

References

- ↑ "An example where diplomatic immunity was waived in the public interest". BBC News. 27 September 2002. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Representations on behalf of the victim's family led to the prosecution of a military attache for manslaughter". BBC News. 17 July 2002. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Herodotos. Histories. Book VII, Ch. 133-134. (pp. 558–559 in the cited version.) Transl. Rawlinson, G. Wordsworth. Ware, Herefordshire. 1996. ISBN 1-85326-466-0.

- ↑ Halsall, Paul. "Gelasius I on Spiritual and Temporal Power, 494".

- ↑ Prawdin, Michael. The Mongol Empire.

- ↑ "Raymond Davis and the Vienna Convention". Jinnah-institute.org. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "diplomatic immunity: West's Encyclopedia of American Law (Full Article) from". Answers.com. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "List of Party States, Declarations and Reservations to Chapter III of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 18 April 1961". UNITED NATIONS TREATY COLLECTION. 16 April 2011.

- ↑ Zabyelina, Yuliya. “Respectable and Professional? A Review of Financial and Economic Misconduct in Diplomatic Relations.” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, Volume 44, pp. 88-102.

- ↑ Christopher Beam (Apr 2010). "Can't Touch This: How far does diplomatic immunity go?". Slate.com.

- 1 2 3 "The Untouchables: Is Diplomatic Immunity Going Too Far?". Reader's Digest.

- ↑ "1984: Libyan embassy shots kill policewoman". BBC News. 17 April 1984. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Thatcher, Margaret, Statement on US bombing of Libya.

- ↑ Uhlig, Mark A. (1 January 1988). "Court Won't Bar Return of Boy In Abuse Case to Zimbabwe". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Wife-beating diplomat ordered home". CBC News. 4 March 1999.

- ↑ Location Settings (14 November 2006). "'Abusive' Kenyan diplomat probed". News24. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Queens: Custody Battle Over Diplomat's Children". The New York Times. 14 November 2006.

- ↑ U.S. Embassy Calls for Release of American Diplomat – U.S. Embassy, Islamabad, Pakistan Archived 1 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- ↑ Carlotta Gall, Mark Mazzetti (March 16, 2011). "Hushed Deal Frees C.I.A. Contractor in Pakistan". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ↑ singh, amoulin (11 May 2012). "Panama diplomat in alleged rape case has full immunity". GMA News.

- ↑ "India-Italy marines row: 'No legal immunity' for envoy Daniele Mancini". BBC News: India. BBC. 18 March 2013.

- 1 2 "Govt wanted sex case diplomat to face charges - Key". New Zealand Herald. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysia to send diplomat back to New Zealand wanted on sex charges". The Independent. 3 July 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysian official on sex charge uses diplomatic immunity to leave NZ". The Guardian. 1 July 2014.

- ↑ "Malaysian envoy gets nine-months detention for indecent assault". The Telegraph. 4 February 2016.

- ↑ "Borodin was gevaar voor kinderen". NOS. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Dutch take legal action over Greenpeace ship in Russia". BBC News. 4 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Report: Diplomat Beat Daughter With Chair Leg But Won't Be Charged". ARL Now. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Netherlands Says Venezuelan Detained in Aruba Has Immunity". WSJ. 27 July 2014. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. Plans Sanctions on Some Venezuelan Officials". WSJ. 30 July 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ “Gambian Diplomats Guilty of Tobacco Fraud”. BBC, 8 December 2014.

- ↑ "ACLU: Abused Domestic Workers of Diplomats Seek Justice From International Commission". Commondreams.org. 15 November 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "American Civil Liberties Union: ACLU Charges Kuwait Government and Diplomats With Abusing Domestic Workers". Aclu.org. 17 January 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ Skandaali Suomessa: Suurlähettiläs piti naista orjatöissä | Kotimaan uutiset | Iltalehti.fi

- ↑ "Use of diplomatic immunity". Irishtimes.com. 11 November 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "American Civil Liberties Union: Swarna v. Al-Awadi – Amicus Brief". Aclu.org. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. Appeals Court Affirms Kuwait Immunity, Rejects Ex-Diplomat Immunity, in Abuse of Domestic Worker Case". Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ↑ "India's foreign minister: Drop charges against diplomat - CNN.com". CNN. 20 December 2013.

- ↑ NDTV, NDTV. "Focus on Saudi Diplomat After Women Allege Gang-Rape, Torture". NDTV. NDTV. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "Saudi diplomat booked for gangrape, police free woman, daughter from his Gurgaon residence". Indian Express. September 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Gurgaon rape case: Accused of rape, Saudi diplomat gets away to Saudi Arabia". Indian Express. September 17, 2015.

- ↑ Fisman, Ray; Miguel, Edward (28 April 2006). "Cultures of Corruption: Evidence from Diplomatic Parking tickets" (PDF). USC FBE APPLIED ECONOMICS WORKSHOP.

- 1 2 JOHN J. GOLDMAN (2001-07-03). "NYC's Diplomatic Take on Tickets". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Diplomats 'owe £58m in London congestion charges'". BBC News. London. 5 July 2012.

- ↑ "New York Times urges US Embassy to pay congestion charge | Greater London Authority". London.gov.uk. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ MICHAEL JANOFSKY (1997-10-09). "Georgian Diplomat Pleads Guilty in Death of Teenage Girl". New York Times.

- ↑ Associated Press (1997-12-20). "Ex-Diplomat Gets 7 Years for Death of Teen in Crash". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Immunity shelters former US Consul from Russian invalid". Vladivostok News. 17 August 2006. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008.

- ↑ "Russia student in diplomatic controversy". New Mexico daily Lobo, From AP. 16 September 2002. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008.

- 1 2 "Former Russian diplomat guilty of involuntary manslaughter". CBC News. 2002-03-19.

- ↑ "Russia Says Diplomat Will Be Tried in Drunk-Driving Case". Los Angeles Times. 2001-02-17.

- ↑ "People in the News, May 2005". Vivid — Romania through international eyes.

- ↑ ""Compact" band bass-player, killed in a car accident caused by a US Embassy employee". Nine O'Clock. 6 December 2004. Retrieved 29 November 2007.

- ↑ "USEU: U.S. Military Law Expert Explains Verdict in Romanian Death". Archived from the original on 8 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ↑ "Canada recalls spitting diplomat". BBC News. 14 December 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Tanzania irked by spitting envoy 15 December 2009

- ↑ The Canadian High Commission Regrets The Incident Involving One Of Its Officials Government of Canada

- ↑ Leong, Wee Keat (10 March 2010). "Former Romanian diplomat "could be criminally involved"". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Teh Joo Lin & Elena Chong (5 March 2010). "I was sent 'flying' : Traffic video shows car swerving and hitting him; teen landed 10m away". The Straits Times. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ "Romanian Embassy responds to MFA". The Straits Times. 23 February 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ↑ Elena Chong & Teh Joo Lin (1 April 2010). "Coroner blames envoy". The Straits Times. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ↑ http://www.interpol.int/public/data/wanted/notices/data/2010/56/2010_15456.asp

- ↑ "Romania Keeps Singapore Updated On Steps Taken In Criminal Case Of Fmr Envoy Ionescu – FM". Mediafax. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "Ex-envoy not protected by immunity". Asiaone. 15 April 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "No diplomatic immunity for Ionescu: MFA". Singapore Law Watch. 16 April 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "UN official booked for accident | Provinces". Dawn.Com. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Daily Times. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jason Straziuso (2 August 2013). "US Diplomat Kills Man in Car Crash, Leaves Kenya". ABC News. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ↑ https://www.yahoo.com/autos/owner-of-beverly-hills-laferrari-does-not-have-129289165617.html

- ↑ http://www.cbsnews.com/news/does-driver-in-beverly-hills-high-speed-race-have-diplomatic-immunity/

- ↑ US diplomat faces murder charges for mowing down man | PAKISTAN - geo.tv

- ↑ "Diplomatic Immunity legal definition of Diplomatic Immunity. Diplomatic Immunity synonyms by the Free Online Law Dictionary". Legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com. 19 July 1988. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- ↑ "Embassy to pay congestion charge". BBC News. 6 April 2006. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ↑ FoxNews.com Mexican Embassy: Official Fired After Getting Caught With White House BlackBerries

- ↑ Meikle, James (8 April 2010). "US national security defence defense, US news, Airline industry (business sector), Air transport (News) ,World news, Business". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Julian Assange: UK 'threat' to arrest Wikileaks founder". BBC. 16 August 2012.

- ↑ "Legal Aspects of Diplomatic Immunity and Privileges". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

Further reading

- David B. Michaels, International privileges and immunities: A case for a universal statute, Springer, July 1971, ISBN 978-9024751266

- "Diplomatic and Consular Immunity: Guidance for Law Enforcement and Judicial Authorities" - United States Department of State Office of Foreign Missions.

External links

- New York City Commission for the United Nations Consular Corp and Protocol

- What's the story on diplomatic immunity? from Straight Dope

- Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, 1961

- Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), 1963

- Misusage of Diplomatic Immunity