Dredging

.png)

Dredging is an excavation activity usually carried out underwater, in shallow seas or freshwater areas with the purpose of gathering up bottom sediments and disposing of them at a different location. This technique is often used to keep waterways navigable. It is also used as a way to replenish sand on some public beaches, where sand has been lost because of coastal erosion. Fishing dredges are used as a technique for catching certain species of edible clams and crabs.

Uses

- Capital: dredging carried out to create a new harbor, berth or waterway, or to deepen existing facilities in order to allow larger ships access. Because capital works usually involve hard material or high-volume works, the work is usually done using a cutter suction dredge or large trailing suction hopper dredge; but for rock works, drilling and blasting along with mechanical excavation may be used.

- Preparatory: work and excavation for future bridges, piers or docks/wharves, often connected with foundation work.

- Maintenance: dredging to deepen or maintain navigable waterways or channels which are threatened to become silted with the passage of time, due to sedimented sand and mud, possibly making them too shallow for navigation. This is often carried out with a trailing suction hopper dredge. Most dredging is for this purpose, and it may also be done to maintain the holding capacity of reservoirs or lakes.

- Land reclamation: dredging to mine sand, clay or rock from the seabed and using it to construct new land elsewhere. This is typically performed by a cutter-suction dredge or trailing suction hopper dredge. The material may also be used for flood or erosion control.

- Beach nourishment: mining sand offshore and placing on a beach to replace sand eroded by storms or wave action. This is done to enhance the recreational and protective function of the beaches, which can be eroded by human activity or by storms. This is typically performed by a cutter-suction dredge or trailing suction hopper dredge.

- Harvesting materials: dredging sediment for elements like gold, diamonds or other valuable trace substances.

- Seabed mining: a possible future use, recovering natural metal ore nodules from the sea's abyssal plains.

- Construction materials: dredging sand and gravels from offshore licensed areas for use in construction industry, principally for use in concrete. Very specialist industry focused in NW Europe using specialized trailing suction hopper dredgers self discharging dry cargo ashore.

- Anti-eutrophication: Dredging is an expensive option for the remediation of eutrophied (or de-oxygenated) water bodies. However, as artificially elevated phosphorus levels in the sediment aggravate the eutrophication process, controlled sediment removal is occasionally the only option for the reclamation of still waters.

- Contaminant remediation: to reclaim areas affected by chemical spills, storm water surges (with urban runoff), and other soil contaminations. Disposal becomes a proportionally large factor in these operations.

- Removing trash and debris: often done in combination with maintenance dredging, this process removes non-natural matter from the bottoms of rivers and canals and harbors.

- Flood prevention: this can help to increase channel depth and therefore increase a channel's capacity for carrying water.

- Peat extraction: in former times, so-called dredging poles or dredge hauls were used on the back of small boats to manually dredge the beds of peat-moor waterways before extracting the peat for use as a fuel. This tradition has now become more or less obsolete and the tools used to do this have also changed significantly.

- Oyster dredging or harvesting: in Louisiana and other states with salt water estuaries that can sustain bottom oyster beds. A heavy metal rectangular scoop device is towed astern of a moving boat with a chain bridle attached to a cable and winch which scoops up oysters as it drags along the bottom. The device is periodically hauled aboard and the oysters in it are sorted and bagged for shipment to an oyster processing facility.

- As a hobby: hobbyists examine their dredged matter to pick out items of potential value, similar to the hobby of metal detecting, or the hobby form of dumpster diving, on land.

Relevance

Without the many and almost non-stop dredging operations worldwide, much of the world's commerce would be impaired, often within a few months, since much of world's goods travel by ship, and need to access harbours or seas via channels. Recreational boating also would be constrained to the smallest vessels. The majority of marine dredging operations (and the disposal of the dredged material) will require that appropriate licences are obtained from the relevant regulatory authorities, and dredging is usually carried out by (or for) harbour companies or corresponding government agencies.

Types of dredging vessels

Suction

- For suction-type excavation out of water, see Suction excavator.

These operate by sucking through a long tube, like some vacuum cleaners but on a larger scale.

A plain suction dredger has no tool at the end of the suction pipe to disturb the material. This is often the most commonly used form of dredging.

Trailing suction

A trailing suction hopper dredger (TSHD) trails its suction pipe when working. The pipe, which is fitted with a dredge drag head, loads the dredge spoil into one or more hoppers in the vessel. When the hoppers are full, the TSHD sails to a disposal area and either dumps the material through doors in the hull or pumps the material out of the hoppers. Some dredges also self-offload using drag buckets and conveyors.

The largest trailing suction hopper dredgers in the world are currently Jan De Nul's Cristobal Colon (launched 4 July 2008[1]) and its sister ship Leiv Eriksson (launched 4 September 2009[2]). Main design specs for the Cristobal Colon and the Leiv Eriksson are: 46,000 cubic metre hopper and a design dredging depth of 155 m.[3] Next largest is HAM 318 (Van Oord) with its 37,293 cubic metre hopper and a maximum dredging depth of 101 m.

Cutter-suction

A cutter-suction dredger's (CSD) suction tube has a cutting mechanism at the suction inlet. The cutting mechanism loosens the bed material and transports it to the suction mouth. The dredged material is usually sucked up by a wear-resistant centrifugal pump and discharged either through a pipe line or to a barge. Cutter-suction dredgers are most often used in geological areas consisting of hard surface materials (for example gravel deposits or surface bedrock) where a standard suction dredger would be ineffective. In recent years, dredgers with more powerful cutters have been built in order to excavate harder rock without the need for blasting.

The two largest cutter suction dredgers in the world are currently (as at August 2009) DEME's D'Artagnan (28,200 kW total installed power)[4] and Jan De Nul's J.F.J. DeNul (27,240 kW).[5] both built by IHC Merwede.

Auger suction

This process functions like a cutter suction dredger, but the cutting tool is a rotating Archimedean screw set at right angles to the suction pipe. The first widely used auger dredges were designed in the 1980s by Mud Cat Dredges, which was run by National Car Rental, but is now a Division of Ellicott Dredges. In 1996, IMS Dredges introduced a self-propelled version of the auger dredge that allows the system to propel itself without the use of anchors or cables. During the 1980s and 1990s auger dredges were primarily used for sludge removal applications from waste water treatment plants. Today, auger dredges are used for a wider variety of applications including river maintenance and sand mining.

The most common auger dredge on the global market today is the Versi-Dredge. The turbidity shroud on auger dredge systems creates a strong suction vacuum, causing much less turbidity than conical (basket) type cutterheads and so they are preferred for environmental applications. The vacuum created by the shroud and the ability to convey material to the pump faster makes auger dredge systems more productive than similar sized conical (basket) type cutterhead dredges.

Jet-lift

These use the Venturi effect of a concentrated high-speed stream of water to pull the nearby water, together with bed material, into a pipe.

Air-lift

An airlift is a type of small suction dredge. It is sometimes used like other dredges. At other times, an airlift is handheld underwater by a diver.[6] It works by blowing air into the pipe, and that air, being lighter than water, rises inside the pipe, dragging water with it.

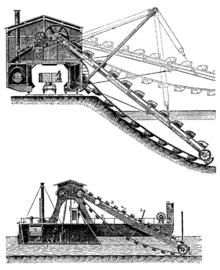

Bucket

A bucket dredger is equipped with a bucket dredge, which is a device that picks up sediment by mechanical means, often with many circulating buckets attached to a wheel or chain. Some bucket dredgers and grab dredgers are powerful enough to rip out coral to make a shipping channel through coral reefs.

Clamshell

A grab dredger picks up seabed material with a clam shell bucket, which hangs from an onboard crane or a crane barge, or is carried by a hydraulic arm, or is mounted like on a dragline. This technique is often used in excavation of bay mud. Most of these dredges are crane barges with spuds.

Backhoe/dipper

A backhoe/dipper dredge has a backhoe like on some excavators. A crude but usable backhoe dredger can be made by mounting a land-type backhoe excavator on a pontoon. The six largest backhoe dredgers in the world are currently the Vitruvius, the Mimar Sinan, Postnik Jakovlev (Jan De Nul), the Samson (DEME), the Simson and the Goliath (Van Oord). They featured barge-mounted excavators. Small backhoe dredgers can be track-mounted and work from the bank of ditches. A backhoe dredger is equipped with a half-open shell. The shell is filled moving towards the machine. Usually dredged material is loaded in barges. This machine is mainly used in harbors and other shallow water.

Water injection

A water injection dredger uses a small jet to inject water under low pressure (to prevent the sediment from exploding into the surrounding waters) into the seabed to bring the sediment in suspension, which then becomes a turbidity current, which flows away down slope, is moved by a second burst of water from the WID or is carried away in natural currents. Water injection results in a lot of sediment in the water which makes measurement with most hydrographic equipment (for instance: singlebeam echosounders) difficult.

Pneumatic

These dredgers use a chamber with inlets, out of which the water is pumped with the inlets closed. It is usually suspended from a crane on land or from a small pontoon or barge. Its effectiveness depends on depth pressure.

Bed leveler

This is a bar or blade which is pulled over the seabed behind any suitable ship or boat. It has an effect similar to that of a bulldozer on land. The chain-operated steam dredger Bertha, built in 1844 to a design by Brunel and now the oldest operational steam vessel in Britain, was of this type.[7]

Krabbelaar

This is an early type of dredger which was formerly used in shallow water in the Netherlands. It was a flat-bottomed boat with spikes sticking out of its bottom. As tide current pulled the boat, the spikes scraped seabed material loose, and the tide current washed the material away, hopefully to deeper water. Krabbelaar is Dutch for "scratcher".

Snagboat

A snagboat is designed to remove big debris such as dead trees and parts of trees from rivers and canals.

Amphibious

Some of these are any of the above types of dredger, which can operate normally, or by extending legs, also known as spuds, so it stands on the seabed with its hull out of the water. Some forms can go on land.

Some of these are land-type backhoe excavators whose wheels are on long hinged legs so it can drive into shallow water and keep its cab out of water. Some of these may not have a floatable hull and, if so, cannot work in deep water.

- Oliver Evans (1755–1819) in 1804 invented an amphibious dredger which was America's first steam-powered road vehicle.

Submersible

These are usually used to recover useful materials from the seabed. Many of them travel on continuous track. A unique variant[8] is intended to walk on legs on the seabed.[9]

Fishing

Fishing dredges are used to collect various species of clams, scallops, oysters or crabs from the seabed. These dredges have the form of a scoop made of chain mesh, and are towed by a fishing boat. Careless dredging can be destructive to the seabed. Nowadays some scallop dredging is replaced by collecting via scuba diving.[10]

Police drag

In some police departments a small dredge (sometimes called a drag) is used to find and recover objects and bodies from underwater. The bodies may be murder victims, or people who committed suicide by drowning, or victims of accidents. It is sometimes pulled by people walking on the bank. Search and rescue units also often use this type of dredge in searching for bodies of missing persons.

Disposal of materials

In a "hopper dredger", the dredged materials end up in a large onboard hold called a "hopper." A suction hopper dredger is usually used for maintenance dredging. A hopper dredge usually has doors in its bottom to empty the dredged materials, but some dredges empty their hoppers by splitting the two halves of their hulls on giant hydraulic hinges. Either way, as the vessel dredges, excess water in the dredged materials is spilled off as the heavier solids settle to the bottom of the hopper. This excess water is returned to the sea to reduce weight and increase the amount of solid material (or slurry) that can be carried in one load. When the hopper is filled with slurry, the dredger stops dredging and goes to a dump site and empties its hopper.

Some hopper dredges are designed so they can also be emptied from above using pumps if dump sites are unavailable or if the dredge material is contaminated. Sometimes the slurry of dredgings and water is pumped straight into pipes which deposit it on nearby land. Other times, it is pumped into barges (also called scows), which deposit it elsewhere while the dredge continues its work.

A number of vessels, notably in the UK and NW Europe de-water the hopper to dry the cargo to enable it to be discharged onto a quayside 'dry'. This is achieved principally using self discharge bucket wheel, drag scraper or excavator via conveyor systems.

When contaminated (toxic) sediments are to be removed, or large volume inland disposal sites are unavailable, dredge slurries are reduced to dry solids via a process known as dewatering. Current dewatering techniques employ either centrifuges, Geotube containers, large textile based filters or polymer flocculant/congealant based apparatus.

In many projects, slurry dewatering is performed in large inland settling pits, although this is becoming less and less common as mechanical dewatering techniques continue to improve.

Similarly, many groups (most notable in east Asia) are performing research towards utilizing dewatered sediments for the production of concretes and construction block, although the high organic content (in many cases) of this material is a hindrance toward such ends.

Environmental impacts

Dredging can create disturbance to aquatic ecosystems, often with adverse impacts. In addition, dredge spoils may contain toxic chemicals that may have an adverse effect on the disposal area; furthermore, the process of dredging often dislodges chemicals residing in benthic substrates and injects them into the water column.

The activity of dredging can create the following principal impacts to the environment:

- Release of toxic chemicals (including heavy metals and PCB) from bottom sediments into the water column.

- Collection of heavy metals lead left by fishing, bullets, 98% mercury reclaimed [natural occurring and left over from gold rush era].

- Short term increases in turbidity, which can affect aquatic species metabolism and interfere with spawning. Suction dredging activity is allowed only during non-spawing time frames set by fish and game (in-water work periods).

- Secondary impacts to marsh productivity from sedimentation

- Tertiary impacts to avifauna which may prey upon contaminated aquatic organisms

- Secondary impacts to aquatic and benthic organisms' metabolism and mortality

- Possible contamination of dredge spoils sites

- Changes to the topography by the creation of "spoil islands" from the accumulated spoil

- Releases toxic compound Tributyltin, a popular biocide used in anti-fouling paint banned in 2008, back into the water.

The nature of dredging operations and possible environmental impacts cause the industry to be closely regulated and a requirement for comprehensive regional environmental impact assessments with continuous monitoring. The U.S. Clean Water Act requires that any discharge of dredged or fill materials into "waters of the United States," including wetlands, is forbidden unless authorized by a permit issued by the Army Corps of Engineers.[11] As a result of the potential impacts to the environment, dredging is restricted to licensed areas only with vessel activity monitored closely using automatic GPS systems.

Major dredging companies

According to a Rabobank outlook report in 2013, the largest dredging companies in the world are in order of size [12]

- China Harbour Engineering (China)

- Jan De Nul (Belgium)

- DEME (Belgium)

- Royal Boskalis Westminster(Netherlands)

- Van Oord Dredging and Marine Contractors (Netherlands)

Images

-

Grab dredge in the Port of Oakland, with San Francisco in the background

-

The 'business end' (excavator) of a Yukon dredge.

-

Profile view of this Yukon dredge tied up to a quay, note the size.

-

April Hamer at Lakes Entrance, Victoria

-

Example of a trailing suction dredger: the Orisant in the port of IJmuiden, Netherlands

-

Grab dredging in Victoria Harbour, Hong Kong

-

Stuyvesant

-

Essayons

-

.jpg)

Alexander von Humboldt of the Jan de Nul fleet

-

Sand mining

-

HR Morris of the Manson Construction fleet, a Cutter Suction Pipeline Dredge, working on Mission Bay, San Diego, CA, USA

-

Dredge ship with barges on Neva bay in Saint Petersburg, Russia

-

Top view of a suction dredger on the Nandu River, Hainan, China

-

A suction dredge barge on the Vistula River, Warsaw, Poland

-

Another suction dredge barge on the Vistula River, Warsaw, Poland

Dredge monitoring software

Dredgers are often equipped with dredge monitoring software to help the dredge operator position the dredger and monitor the current dredge level. The monitoring software often uses Real Time Kinematic satellite navigation to accurately record where the machine has been operating and to what depth the machine has dredged to.

See also

- Dredge ball joint, connection between 2 pipes that are used to transport mixture of water and sand from a dredger to the discharging area

- Dredge drag head

- Navigability

- Peace in Africa (ship), a diamond-mining dredger

- Queen of the Netherlands (ship), a big dredger

- River engineering for inland dredging and other river management systems

- Waterway

- Weeks Marine, a dredging company

- WT Preston, a snagboat

- Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Company, the largest dredging company in North America

References

- ↑ "Jan de Nul's mega trailer Cristóbal Colón launched - Dredging News Online". Sandandgravel.com. 7 July 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Keel-laying ceremony for Jan de Nul's Leiv Eiriksson held - Dredging News Online". Sandandgravel.com. 1 September 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Jan De Nul Group". Jandenul.com. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "DEME: Creating land for the future". Deme.be. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "J.F.J. De Nul | Jan De Nul Group". Jan De Nul Group. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Robbins, R (2006). "USAP Surface-Supplied Diving.". In: Lang, MA and Smith, NE (eds.). Proceedings of Advanced Scientific Diving Workshop: February 23–24, 2006, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ↑ "Bertha". World of Boats. Eyemouth, Scotland: Eyemouth Marine Centre. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ↑ "National Institute of Oceanography, India". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Concept of a mathematical model for prediction of major design parameters of a submersible dredger/miner" by Sritama Sarkar, Neil Bose, Mridul Sarkar, and Dan Walker, in "3rd Indian National Conference on Harbour and Ocean Engineering, National Institute of Oceanography", Dona Paula, Goa 403 004 India, 7–9 December 2004

- ↑ Walker, Margaret (1991). "What price Tasmanian scallops? A report of morbidity and mortality associated with the scallop diving season in Tasmania 1990.". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 21 (1). Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Clean Water Act, 33 U.S.C. § 1311, 33 U.S.C. § 1362, 33 U.S.C. § 1344.

- ↑ http://www.dredging.org/media/ceda/org/documents/resources/othersonline/rabobank-outlook_dredging_september_2013.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dredge ships. |

- World of Boats (EISCA) Collection ~ Isambard Kingdom Brunel's Bertha

- Directory of Dredgers (a close to exhaustive private collection of dredger photographs)

- News and Equipment Exchange (Latest global news and equipment)

- Dredging News

- Qingdao Dredging Machinery (dredging in China)

- Dredging and Spoil Disposal Policy (pdf)(from the Australian Government)

- The Art of Dredging (Knowledge sharing)

- USACE Dredging Information System (from the US Army Corps of Engineers)

- Google search for images of clamshell grabs