Eadwig

| Eadwig | |

|---|---|

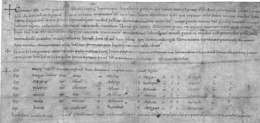

Eadwig in the early fourteenth century Genealogical Roll of the Kings of England | |

| King of the English | |

| Tenure | 23 November 955 – 1 October 959 |

| Predecessor | Eadred |

| Successor | Edgar |

| Born |

941? Wessex, England |

| Died |

October 1, 959 (approx. 18) Gloucester, England |

| Burial | Winchester Cathedral |

| Spouse | Ælfgifu (annulled) |

| House | Wessex |

| Father | Edmund, King of England |

| Mother | Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury |

| Religion | Catholicism (pre-reformation) |

Eadwig, also spelled Edwy (died 1 October 959), usually called the All-Fair,[1] was King of England from 955 until his premature death in 959.

The elder son of King Edmund I and his Queen Ælfgifu of Shaftesbury, Eadwig became King in 955 following the death of his uncle Eadred. Eadwig's short reign was tarnished by disputes with nobles and men of the church, including Dunstan and Archbishop Oda.

Eadwig died in 959, having ruled less than four years. He was buried in the capital Winchester. His brother Edgar the Peaceful succeeded him.

King of England

Feud with Dunstan

According to one legend, the feud with Dunstan began on the day of Eadwig's consecration, when he failed to attend a meeting of nobles. When Dunstan eventually found the young monarch, he was cavorting with a noblewoman named Æthelgifu and refused to return with the bishop. Infuriated by this, Dunstan dragged Eadwig back and forced him to renounce the girl as a "strumpet". Later realizing that he had provoked the king, Dunstan fled to the apparent sanctuary of his cloister, but Eadwig, incited by Æthelgifu, followed him and plundered the monastery. Though Dunstan managed to escape, he refused to return to England until after Eadwig's death.

The contemporary record of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reports Eadwig's accession and Dunstan fleeing England, but does not explain why Dunstan fled. Thus this report of a feud between Eadwig and Dunstan could either have been based on a true incident of a political quarrel for power between a young king and powerful church officials who wished to control the king and who later spread this legend to blacken his reputation, or it could be mere folklore; the Chronicle also tells of Odo putting aside the King's marriage on the grounds Eadwig and his wife were "too related".

_obverse.jpg)

The account of the quarrel with Dunstan and Cynesige, bishop of Lichfield at the coronation feast is recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and in the later chronicle of John of Worcester and was written by monks supportive of Dunstan's position. The "cavorting" in question consisted of Eadwig (then only 16) being away from the feast with Ælfgifu and her mother Æthelgifu. He later married Ælfgifu, who seems to have been the sister of Æthelweard the Chronicler. Æthelweard describes himself as the "grandson's grandson" of King Æthelred I. Eadwig was the son of King Edmund the Magnificent, grandson of King Edward the Elder, great-grandson of King Alfred the Great, and therefore great-great-nephew of King Æthelred I. Eadwig and Ælfgifu were therefore third cousins once removed.

Annulment of marriage

The annulment of the marriage of Eadwig and Ælfgifu is unusual in that it was against their will, clearly politically motivated by the supporters of Dunstan. The Church at the time regarded any union within seven degrees of consanguinity as incestuous.[2] (This was reduced to four in 1215.) At the time, "degree" was reached by counting up to the common ancestor and back: a second cousin would have been related within the sixth degree.

Division of the Kingdom

Dunstan, whilst in exile, became influenced by the Benedictines of Flanders. A pro-Dunstan, pro-Benedictine party began to form around Athelstan Half-King's domain of East Anglia and supporting Eadwig's younger brother Edgar.

Frustrated by the king's impositions and supported by Archbishop Oda of Canterbury, the Thanes of Mercia and Northumbria switched their allegiance to Eadwig's brother Edgar. In 957, rather than see the country descend into civil war, the nobles agreed to divide the kingdom along the Thames, with Eadwig keeping Wessex and Kent in the south and Edgar ruling in the north.

Charter evidence

Eadwig is known for his remarkable generosity in giving away land. In 956 alone, his sixty odd gifts of land make up around 5% of all genuine Anglo-Saxon charters. No known ruler in Europe matched that yearly total before the twelfth century, and his cessions are plausibly attributed to political insecurity.[3]

Eadwig died at a young age in 959, in circumstances which remain unknown. He was succeeded by his brother Edgar the Peaceful, who reunited the kingdom.

In art and literature

The history of Eadwig's reign caught the British imagination in the later 18th century, and was represented in paintings and drama, in particular, by numerous works to 1850. Artists who tackled the subjects it suggested included William Bromley, William Hamilton, William Dyce, Richard Dadd, and Thomas Roods. Literary works were written by Thomas Sedgwick Whalley, Thomas Warwick and Frances Burney.[4]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eadwig. |

References

- ↑ Britain Express - English Monarchs

- ↑ Constance B. Bouchard, 'Consanguinity and Noble Marriages in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries', Speculum, Vol. 56, No. 2 (Apr., 1981), pp. 269-70

- ↑ Chris Wickham, 'Problems in Doing Comparative History', pp. 19-20, in Challenging the Boundaries of Medieval History: The Legacy of Timothy Reuter, Patricia Skinner, ed, Brepols 2009.

- ↑ Keynes, Simon. "Eadwig". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8572. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Eadred |

King of the English 955–959 |

Succeeded by Edgar |