Edmund the Martyr

| Edmund | |

|---|---|

| King of the East Angles | |

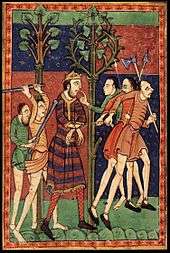

A medieval illumination depicting the death of Edmund the Martyr on 20 November 869 by the Vikings. | |

| Reign | 25 December 855 (traditionally) – 20 November 869 (or 870) |

| Predecessor | Ethelweard |

| Successor | Oswald |

| Born | by tradition 841 |

| Died |

killed in battle 20 November 869 see ...legends |

| House | unknown |

| Father | possibly Æthelweard |

| Religion | Christian |

Edmund the Martyr (also known as St Edmund or Edmund of East Anglia, died 20 November 869)[note 1] was king of East Anglia from about 855 until his death.

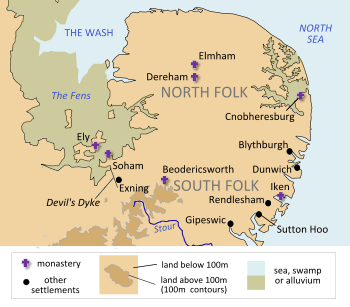

Almost nothing is known about Edmund. He is thought to have been of East Anglian origin and was first mentioned in an annal of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written some years after his death. The kingdom of East Anglia was devastated by the Vikings, who destroyed any contemporary evidence of his reign. Later writers produced fictitious accounts of his life, asserting that he was born in 841, the son of Æthelweard, an obscure East Anglian king, whom it was said Edmund succeeded when he was fourteen (or alternatively that he was the youngest son of a Germanic king named 'Alcmund'). Later versions of Edmund's life relate that he was crowned on 25 December 855 at Burna (probably Bures St. Mary in Suffolk), which at that time functioned as the royal capital,[2] and that he became a model king.

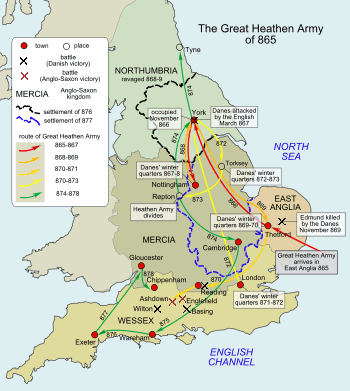

In 869, the Great Heathen Army advanced on East Anglia and killed Edmund. He may have been slain by the Danes in battle, but by tradition he met his death at an unidentified place known as Haegelisdun, after he refused the Danes' demand that he renounce Christ: the Danes beat him, shot him with arrows and then beheaded him, on the orders of Ivar the Boneless and his brother Ubba. According to one legend, his head was then thrown into the forest, but was found safe by searchers after following the cries of a wolf that was calling, "Hic, Hic, Hic" – "Here, Here, Here". Commentators have noted how Edmund's death bears resemblance to the fate suffered by St Sebastian, St Denis and St Mary of Egypt.

A coinage commemorating Edmund was minted from around the time East Anglia was absorbed by the kingdom of Wessex and a popular cult emerged. In about 986, Abbo of Fleury wrote of his life and martyrdom. The saint's remains were temporarily moved from Bury St Edmunds to London for safekeeping in 1010. His shrine at Bury was visited by many kings, including Canute, who was responsible for rebuilding the abbey: the stone church was rebuilt again in 1095. During the Middle Ages, when Edmund was regarded as the patron saint of England, Bury and its magnificent abbey grew wealthy, but during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, his shrine was destroyed. The mediaeval manuscripts and other works of art relating to Edmund that have survived include Abbo's Passio Sancti Eadmundi, John Lydgate's 14th-century Life, the Wilton Diptych and a number of church wall paintings.

King of the East Angles

Accession and rule

Edmund is first mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle annal for 870, which was compiled twenty years after his death.[3] By tradition, Edmund is thought to have been born in 841 and to have acceded to the East Anglian throne in around 855.[4] Nothing is known of his life or reign, as no contemporary East Anglian documents from this period have survived. The devastation in East Anglia that was caused by the Vikings is thought to have destroyed any books or charters that referred to Edmund[5] and the lack of contemporary evidence means that it is not known for certain when his reign began, or his age when he became king. Later medieval chroniclers have provided dubious accounts of his life, in the absence of any real details. The most credible theory for Edmund’s parentage suggests Ealhhere, brother-in-law to King Æthelstan of Kent, as Edmund’s father and Edith (Æthelstan’s sister) as Edmund’s mother.[6]

Edmund cannot be placed within any ruling dynasty. Numismatic evidence suggests he succeeded Æthelweard. According to the historian Susan Ridyard, Abbo of Fleury's statement that Edmund was 'ex antiquorum Saxonum nobili prosapia oriundus' can be taken to mean that he was descended from a noble and ancient race.[7]

It is known that a variety of different coins were minted by Edmund's moneyers during his reign.[8] The letters AN, standing for 'Anglia', only appear on the coins of Edmund and Æthelstan of East Anglia: they appear on Edmund's coins as part of the phrase + EADMUND REX AN. Later specimens read + EADMUND REX and so it is possible for his coins to be divided chronologically.[9] Otherwise, no chronology for his coins has been confirmed.[10]

Death

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which generally described few matters relating to the East Angles and their rulers, is the only source for a description of the events for the year 869 that led to the defeat of Edmund's army at the hands of the Danes. It relates that "Her rad se here ofer Mierce innan East Engle and wiñt setl namon. æt Đeodforda. And þy wint' Eadmund cying him wiþ feaht. and þa Deniscan sige naman þone cyning ofslogon. and þæt lond all ge eodon." – 'here the army rode across Mercia into East Anglia, and took winter-quarters at Thetford; and that winter King Edmund fought against them, and the Danish took the victory, and killed the king and conquered all that land'.[11][12] By tradition the leaders who slew the king were Ivar the Boneless and his brother Ubba.

Along with other forces, the Great Heathen Army then invaded Wessex, perhaps in December 870 (within a few weeks of killing Edmund) or after having spent a year pillaging and consolidating their position in East Anglia, before proceeding to attack Mercia and Northumbria.[13][14]

Memorial coinage

_of_Edmund_the_Martyr.jpg)

Edmund's body was buried in a wooden chapel near to where he was killed, but was later transferred to Beadoriceworth (modern Bury St Edmunds), where in 925 Athelstan founded a community devoted to the new cult.[15] Thirty years after Edmund's death, he was venerated by the Vikings of East Anglia, who produced a coinage to commemorate him.[16] The coinage was minted from around 895 to 915 (close to the time when East Anglia was conquered by Edward the Elder of Wessex) and was based on the design of coins produced during Edmund's reign. All the pennies and (more rarely) half-pennies that were produced read SCE EADMVND REX—'O St Edmund the king!'. Some of them have a legend that provides evidence that the Vikings experimented with their initial design.[17]

The St. Edmund memorial coins were minted in great quantities by a group of more than 70 moneyers, many of whom appear to have originated from the continent: over 1800 individual specimens were found when the great Cuerdale Hoard was discovered in 1840.[18] The coins would have been widely used within the Danelaw and many single items have mainly been found in the east of England, but the exact locations of the mints where they were made are not known with certainty: scholars have assumed that they were made in East Anglia.[19]

Veneration

| Saint Edmund the Martyr | |

|---|---|

Edmund being crowned by angels, from a 13th-century manuscript. | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Major shrine | Bury St Edmunds, destroyed |

| Feast | 20 November |

| Attributes | Crowned and robed king holding a scepter, orb, arrow, or a sword, wolf, severed head |

| Patronage | Kings, pandemics, the Roman Catholic diocese of East Anglia, Douai Abbey, wolves, torture victims, protection from the plague |

Cult at Bury St Edmunds

During the 11th century a stone church was built in Bury St. Edmunds, which was replaced by a larger church in 1095, into which Edmund's relics were translated. The abbey's power grew upon being given jurisdiction over the growing town in 1028 and the creation in 1044,[15] of the geographical and political area of the Liberty of Saint Edmund, established by Edward the Confessor, which remained a separate jurisdiction under the control of the abbot of Bury St Edmunds Abbey until the dissolution of the monasteries.

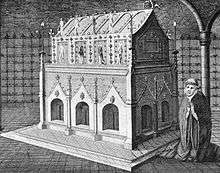

The shrine at Bury St Edmunds soon became one of the most famous and wealthy pilgrimage locations in England. In 1010, Edmund's remains were translated to London to protect them from the Vikings, where they were kept for three years before being returned to Bury.[15] For centuries the shrine was visited by various kings of England, many of whom gave generously to the abbey: Sweyn's son, King Canute, converted to Christianity and rebuilt the abbey at Bury St Edmunds. In 1020, he made a pilgrimage and offered his own crown upon the shrine as atonement for the sins of his forefathers.

The town arose as the wealth and fame of the abbey grew. After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the abbot planned out over 300 new houses within a grid-iron pattern at a location that was close to the abbey precincts.[20] Edmund's cult was promoted and flourished, but it declined in subsequent years and the saint did not reappear in any liturgical calendars until the appearance of Abbo of Fleury's Passio Sancti Eadmundi in the 12th century.[21] King John is said to have given a great sapphire and a precious stone set in gold to the shrine, which he was permitted to keep upon the condition that it was returned to the abbey when he died.[22]

Edmund's shrine was destroyed in 1539, during the English Reformation. According to a letter (which now belongs to the Cotton Collection in the British Library), the shrine was defaced, and silver and gold to the value of over 5000 marks was taken away. On 4 November 1539 the abbot and his monks were expelled and the abbey was dissolved.[23]

Cult at Toulouse

After the Battle of Lincoln (1217), it was traditionally claimed that Edmund's body was stolen by Count of Melun and subsequently donated to the Basilica of Saint-Sernin in the French city of Toulouse by the Dauphin (later Louis XIII of France).[24] The first record of this is a relic list for Saint-Sernin of around 1425, which included St Edmund among the basilica's relics.[24] After the city was saved from the plague in the years from 1628 to 1631 — by the saint's intercessions — the city built, in 1644,[24] a new shrine for his relics in gratitude for its deliverance: his cult flourished there for over two centuries. Edmund's shrine was of silver and adorned with solid silver statues and when his relics were translated to it, the population came for eight days to honour the saint.[25]

Relics at Arundel Castle

In 1901, the Archbishop of Westminster, Herbert Vaughan, received some relics from the basilica of Saint-Sernin. The relics, believed at the time to be those of St Edmund, were intended for the high altar of London's Westminster Cathedral, which was then under construction.[24]

The acceptance of the relics required the intercession of Pope Leo XIII, after an initial refusal by the church in France.[26] Upon their arrival in England, they were housed in the Fitzalan Chapel at Arundel Castle, prior to their translation to Westminster. Although the relics had been verified and catalogued in 1644 for interment in the new shrine and in 1874 when two pieces were given to Cardinal Manning, concerns were raised by Dr. Montague James and Dr Charles Biggs about their validity in The Times. They remained at Arundel under the care of the Duke of Norfolk, whilst a historical commission was set up by Cardinal Vaughan and Archbishop Germain of Saint-Sernin. They remain to this day at Arundel.[27] In 1966, three teeth from the collection of relics from France were donated to Douai Abbey.[24]

The Passio Sancti Eadmundi

Edmund's cult re-emerged in the 10th century and the site of his burial grew wealthy as a result of receiving grants of land from royally connected benefactors. In about 986, the monks of Ramsey Abbey commissioned Abbo of Fleury to write an account of the saint's life and early cult.[28][29] In his preface or dedicatory epistle Abbo addresses the work to St Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury 960-988. Dunstan himself is the source of the story of the martyrdom, which long before he heard told, in the presence of King Æthelstan, by an old man who swore an oath that he had been Edmund's own sword-bearer (armiger) on the fatal day.[30] Abbo therefore clearly makes Dunstan, then still living and the recipient of his work, the authority for what he has to say.

According to Abbo, Edmund was "ex antiquorum Saxonum nobili prosapia oriundus".[31] This statement has confused later translators into thinking that Edmund was of continental Old Saxon origin. However the historian Steven Plunkett notes that Abbo, describing the Migration Age settlement of the East Anglian region (Eastengle) at the opening of his work, attributed that occupation to 'Saxons' (the Jutes and Angles going elsewhere): therefore by the use of the term 'of the noble lineage of the old Saxons' for Edmund, he was not attempting to make a distinction between Edmund's own ancestry and that of the people over whom he ruled.[32]

In Abbo's version of events, the king refused to meet the Danes in battle, preferring to die a martyr's death. The historian Susan Ridyard maintains that Edmund's martyrdom cannot be proved and the nature of his fate — whether he died fighting or was cruelly murdered in the battle's aftermath — cannot be read from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. She notes that the story that Edmund had an armour-bearer implies that he would have been a warrior king who was prepared to fight the Vikings on the battlefield, but she acknowledges the possibility that later accounts belong to "the realm of hagiographical fantasy".[33]

"King Edmund, against whom Ivar advanced, stood inside his hall, and mindful of the Saviour, threw out his weapons. He wanted to match the example of Christ, who forbade Peter to win the cruel Jews with weapons. Lo! the impious one then bound Edmund and insulted him ignominiously, and beat him with rods, and afterwards led the devout king to a firm living tree, and tied him there with strong bonds, and beat him with whips. In between the whip lashes, Edmund called out with true belief in the Saviour Christ. Because of his belief, because he called to Christ to aid him, the heathens became furiously angry. They then shot spears at him, as if it was a game, until he was entirely covered with their missiles, like the bristles of a hedgehog (just like St. Sebastian was).

When Ivar the impious pirate saw that the noble king would not forsake Christ, but with resolute faith called after Him, he ordered Edmund beheaded, and the heathens did so. While Edmund still called out to Christ, the heathen dragged the holy man to his death, and with one stroke struck off his head, and his soul journeyed happily to Christ."

Ælfric of Eynsham, Old English paraphrase of Abbo of Fleury, 'Passio Sancti Eadmundi' .[34]

Abbo named one of Edmund's killers as Hinguar, who can probably be identified with Ivarr inn beinlausi (Ivar the Boneless), son of Ragnar Lodbrok.[35] After describing the horrific manner of Edmund's death, the Passio continued the story. His severed head was thrown into the wood. As Edmund's followers went seeking, calling out "Where are you, friend?" the head answered, "Here, here, here," until at last they found it, clasped between a wolf's paws, protected from other animals and uneaten. The villagers then praised God and the wolf that served him. It walked tamely beside them, before vanishing back into the forest.[30]

The body was buried in a coffin and later translated to Beodericsworth, but Abbo failed to date either events,[36] although from the text it can be seen that he believed that the relics had been taken to Beodericsworth by the time that Theodred became Bishop of London in around 926.[37] Upon exhumation of the body, a miracle was discovered. All the arrow wounds upon Edmund's corpse had healed and his head was reattached. The only evidence of decapitation was a line around his neck and his skin was still soft and fresh, as if he had been sleeping.[30] [note 2] The last recorded inspection of the body whilst at Bury St Edmunds was in 1198.[24][39]

The resemblance between the deaths of Saint Sebastian and St Edmund was remarked upon by Abbo: both saints were attacked by archers, although only Edmund is supposed to have been decapitated. His death bears somes resemblance to the fate suffered by other saints: St Denis was whipped and beheaded and the body of Mary of Egypt was said to have been guarded by a lion.[40] Gransden describes Abbo's Passio as "little more that a hotch-potch of hagiographical commonplaces" and argues that Abbo's ignorance of what actually happened to Edmund would have led him to use aspects of the Lives of well known saints such as Sebastian and Denis as models for his version of Edmund's martydom. Gransden acknowledges that there are some aspects of the story—such as the appearance of the wolf that guards Edmund's head—that do not have exact parallels elsewhere.[41]

Other commentators have suggested that the manner of St Edmund's death, veneration and culthood define him as a sacral king. It has been argued that St Edmund's story was informed by common Celtic and Germanic notions of sacred kingship. Comparable kings who also embodied theories of divinely-ordained rule, rightful sovereignty and the binding links between king, land and society, include: Conaire Mór, Cormac mac Cuilennáin, King Dómaldi and Halfdan the Black.[42]

Medieval hagiographies and legends

De Infantia Sancti Edmundi, a fictitious 12th century hagiography of Edmund's early life by Geoffrey of Wells, represented him as the youngest son of 'Alcmund', a Saxon king of Germanic descent. 'Alcmund' may never have existed.[43]

Edmund's fictitious continental origins were later expanded into legends which spoke of his parentage, his birth at Nuremberg, his adoption by Offa of Mercia, his nomination as successor to the king and his landing at Hunstanton on the North Norfolk coast to claim his kingdom.[31] Other accounts state that his father was the king he succeeded, Æthelweard of East Anglia, who died in 854, apparently when Edmund was a boy of fourteen.

He was said to have been crowned by St Humbert (Bishop Humbert of Elmham) on 25 December 855, at a location known as Burna (probably Bures St. Mary in Suffolk) which at that time functioned as the royal capital.[2] Later versions of his life recorded that he was a model king who treated all his subjects with equal justice and who was unbending to flatterers. It was written that he withdrew for a year to his royal tower at Hunstanton and learned the whole Psalter, so that he could recite it from memory.[43][44]

Edmund may have been killed at Hoxne, in Suffolk.[45] His martyrdom is mentioned in a charter that was written when the church and chapel at Hoxne were granted to Norwich Priory in 1101. Place-name evidence has been used to link the name of Hoxne with Haegelisdun, named by Abbo of Fleury as the site of Edmund's martyrdom, but this evidence is dismissed by the historian Peter Warner.[46] The association of Edmund's cult with the village has continued to the present day.[note 3] Dernford, Cambridgeshire[48] and Bradfield St Clare[49][50] (near Bury St Edmunds) are other possible sites for where Edmund was martyred. [note 4]

The ancient wooden church of St Andrew, Greensted-juxta-Ongar, is said to have been a resting place for his body on the way to Bury St Edmunds in 1013[51]

Banner

In Bernard Burke's Vicissitudes of Families, published in 1869, Burke proposed that Edmund's banner was among those borne during the Norman invasion of Ireland, after which the three crowns on a blue background became the standard for Ireland during the Plantagenet era. Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, Robert Fitz-Stephen and Raymond le Gros who all featured prominently in the Anglo-Norman invasion, dedicated a chapel of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin to Edmund.[53] When the Scottish castle at Caevlerlock was taken by Edward I of England in 1300, the banners of Edmund, St George and Edward the Confessor were displayed by the victorious English from the castle battlements, as "powerful, unifying symbols of the holy guardians and supporters of their cause".[54] According to the antiquarian Sir Harris Nicolas' account of the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, five banners were flown on the English side, one of which was probably that of St Edmund.[55]

In a preface to the Life of the saint written by the poet John Lydgate, in which Edmund's banners are described,[note 5][57] the three crowns are said to represent Edmund's martyrdom, virginity and kingship.[58]

Patronages

Edmund is the patron saint of pandemics as well as kings,[59] the Roman Catholic diocese of East Anglia,[60] and Douai Abbey in Berkshire.[61] Churches dedicated to his memory are to be found all over England, including St Edmund the King and Martyr's Church in London, designed by Sir Christopher Wren during the 1670s. St Edmund King and Martyr's Church in Godalming, Surrey was dedicated to Edmund because its founder was from Suffolk.[62]

During the Middle Ages, St George replaced Edmund as the patron saint of England when Edward III associated George with the Order of the Garter.[20] In 2006, a group that included BBC Radio Suffolk and the East Anglian Daily Times failed in their campaign to reinstate Edmund.[note 6] In 2013 another campaign[64] to reinstate St Edmund as patron saint was begun with the backing of representatives from businesses, Churches, radio and local politicians.[65]

St Edmund in the arts

The veneration of Edmund throughout the centuries has left a legacy of noteworthy works of art.

A beautifully illustrated copy of Abbo of Fleury's Passio Sancti Eadmundi, made at Bury St Edmunds in around 1130 is now kept at the Morgan Library in New York City.[15]

The copy of John Lydgate's 15th century Life written for Henry VI of England is now in the British Library.[66] The Wilton Diptych was painted during the reign of Richard II of England and is the most famous representation of Edmund in art. Painted on oak panels, it shows Richard kneeling in front of three saints—one of whom is Edmund—as they present the young king to the Virgin and Child.[15][67]

The poet John Lydgate (1370–1451), who lived all his life in Bury St Edmunds, presented his twelve-year-old king Henry VI of England with a long poem (now known as Metrical Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund) when Henry came to the town in 1433 and stayed at the abbey for four months.[68] The book is now kept by the British Library in London.[56]

Edmund's martyrdom features on several medieval wall-paintings to be found in churches across England.[69]

The market town of Bury St Edmunds features several representations of St Edmund, most notably a recently commissioned contemporary artwork designed by Emmanuel O’Brien, constructed by Nigel Kaines of Designs on Metal in 2011.

Edmund appears as a fictional character in Bernard Cornwell's novel The Last Kingdom.

Edmund is the subject of the song "Barbarian" by The Darkness on the album Last of Our Kind.

- Depictions of St Edmund

-

St Edmund. Public artwork, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk. 2011. Designed by Emmanuel O’Brien, constructed by Nigel Kaines, Designs on Metal.

-

The Martyrdom of St. Edmund painted by Brian Whelan hangs in the Lady Chapel of the St. Edmundsbury Cathedral.

-

Edmund as depicted on the west front of Salisbury Cathedral.

-

.jpg)

The Wilton Diptych. Edmund is shown with Edward the Confessor, John the Baptist and Richard II.

-

A statue of the saint outside St. Edmund's Church, in Southwold.

The saint features in a romantic poem, Athelston, whose 15th-century author is unknown. In the climactic scene of the poem, Edyff, the sister of King 'Athelston' of England, gives birth to Edmund after passing through a ritual ordeal by fire.[70]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The year of Edmund's death may have been 870, according to some calculations. The uncertainty has arisen because the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle sometimes began in September, meaning that an event that took place in November 869 (according to the modern calendar) would have been recorded by the Anglo-Saxons as having taken place in 870.[1]

- ↑ These details induced the writers of the British Museum's account of the bog body called Lindow Man to suggest that the body of St Edmund recovered in the fens "was in fact a prehistoric bog body, and that in trying to find their murdered king, his people had recovered the remains of a sacred king of the old religion still bearing the marks of his ritual strangulation".[38]

- ↑ Until 1849, an old tree stood in Hoxne Park that was believed to be where Edmund had been martyred. In the heart of the tree, an arrow head was found. A piece of the tree was used to form part of an altar of a church dedicated to Edmund. Another legend relates that after being routed in battle, Edmund hid under the Goldbrook bridge at Hoxne, but his hiding place was revealed to a wedding party, who gave him away his enemies.[47]

- ↑ However, there is a spot where places named in the early accounts occur close together. A field called 'Hellesdon' lay just south of Pitcher's Green at Bradfield St Clare; Sutton Hall stands a mile south of Bradfield St Clare on the parish boundary; Kingshall Farm, Kingshall Green and Kingshall Street occur in Rougham, two miles to the north. Bradfield St Clare is approximately six miles from Bury St Edmunds, which was an Anglo-Saxon royal vill (settlement). A monastery already existed, founded by King Sigeberht in 633AD. There was also a building called Bradfield Hall that stood within the St Edmund's Abbey, and accounts show that the Abbey's Cellarer paid rent for small pieces of land at Bradfield St Clare Hall, (6 shillings 8d pence)and Suttonhall (3s 2d.).

- ↑ See the British Library image of the three crowns banner from Lydgate's book.[56]

- ↑ The Bury St Edmunds MP David Ruffley had taken up the cause and helped deliver a large petition to the government in London. Prime Minister Tony Blair rejected the request; however their attempt was successful on another level, "St Edmund (was) named patron saint of Suffolk...the high point of a successful campaign which was launched by Breakfast show presenter Mark Murphy and producer Emily Fellows in the autumn of 2006".[63]

Footnotes

- ↑ Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. xv.

- 1 2 Saint Edmund King and Martyr. 1970. p. 19. ISBN 9780900963186.

- ↑ "This year the army rode over Mercia into East-Anglia, and there fixed their winter-quarters at Thetford. And in the winter King Edmund fought with them; but the Danes gained the victory, and slew the king; whereupon they overran all that land, and destroyed all the monasteries to which they came. The names of the leaders who slew the king were Hingwar and Hubba. At the same time came they to Medhamsted, burning and breaking, and slaying abbot and monks, and all that they there found. They made such havoc there, that a monastery, which was before full rich, was now reduced to nothing. The same year died Archbishop Ceolnoth; and Ethered, Bishop of Witshire, was chosen Archbishop of Canterbury." (trans. Ingram 1823).

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 61.

- ↑ Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, p. 58.

- ↑ Hervey, "Corolla Sancti Eadmundi. The Garland of Saint Edmund, King and Martyr", Preface 43.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 217.

- ↑ "Treasure hunters found nearly 1,000 items in 2012". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 294.

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 588.

- ↑ Earle, Two of the Saxon Chronicles Parallel, pp. 72, 74.

- ↑ Swanton, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 70.

- ↑ Yorke, Wessex in the Early Middle Ages, p. 109.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Farmer, The Oxford Dictionary of Saints: Edmund

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 305.

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 320.

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 319.

- ↑ Grierson and Blackburn, Medieval European Coinage, p. 320.

- 1 2 Cantor, The English Medieval Landscape, p. 176.

- ↑ Gransden, Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Yates, History and Antiquities of the Abbey of St Edmunds Bury, part II p. 40.

- ↑ Yates, History and Antiquities of the Abbey of St Edmunds Bury, part I, pp. 232–235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gem, Richard (1998). Gransden, Antonia, ed. "A Scientific Examination of the Relics of St Edmund at Arundel Castle". Bury St Edmunds: Medieval Art, Architecture, Archaeology and Economy. British Archaeological Association Confirmed Transactions XX: 45–59.

- ↑ Catholic World, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Saint Edmund King and Martyr. 1970. p. 78. ISBN 9780900963186.

- ↑ Saint Edmund King and Martyr. 1970. p. 79. ISBN 9780900963186.

- ↑ Abbo, Passio Sancti Edmundi, in Francis Hervey (Ed.), Corolla Sancti Edmundi: The Garland of Saint Edmund, King and Martyr (John Murray: London 1907), pp. 6-59. (parallel text in Latin and English translation). The Martyrdom is in chapter X (10).

- ↑ Gransden, Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England, pp. 45–46.

- 1 2 3 Abbo of Fleury, Life of St. Edmund.

- 1 2 Mawer, Encyclopedia Britannica, volume 8, pp. 947–948.

- ↑ Plunkett, Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times, pp. 202–212.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England. pp.66–67.

- ↑ Ælfric of Eynsham. See external link.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England. p. 67.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England. p. 213.

- ↑ Ridyard, The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England. p. 231.

- ↑ Stead et al, Lindow Man: The Body in the Bog, p. 175.

- ↑ Saint Edmund King and Martyr. 1970. p. 51. ISBN 9780900963186.

- ↑ Gransden, Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England, p. 87.

- ↑ Gransden, Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Taylor, Mark (2013). Edmund: the Untold Story of the Martyr-King and His Kingdom. Fordaro. pp. 27–43. ISBN 978-0992721107.

- 1 2 Catholic Encyclopedia, p. 295.

- ↑ Saint Edmund King and Martyr. 1970. p. 16. ISBN 9780900963186.

- ↑ Warner, Origins of Suffolk, p. 219.

- ↑ Warner, Origins of Suffolk, pp. 139, 141.

- ↑ 'Saint Edmund: England's Original Patron Saint', at Hoxne's website.

- ↑ Scarle, R.D. Do you know where King Edmund died in 869 AD?. The Good Grid Guide. Cambridge Archaeology.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History Volume 35 part 3. 1983. p. 223.

- ↑ Reimer, Stephen R. "The Lives of Ss. Edmund and Fremund: Introduction". The Canon of John Lydgate Project. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Jennifer Westwood, Albion: a Guide to Legendary Britain, Book Club Associates (1986) ISBN 978-0881621280 (p. 152)

- ↑ A Guide to the Town, Abbey and Antiquities of Bury St. Edmunds (author not stated on title page), Bury St Edmunds, 1836, p.93, footnote

- ↑ Kennedy, The Arms of Ireland: Medieval and Modern, notes 2 and 3.

- ↑ Altmann, The Court Reconvenes, p. 15.

- ↑ Nicolas, History of the Battle of Agincourt, p. 115.

- 1 2 British Library online Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts: Harley 2278 f.3v (Arms of Bury).

- ↑ Frantzen, Bloody Good, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ Preble, Origin and History of the American Flag, p. 123

- ↑ Ball, Encyclopaedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, p. 276.

- ↑ Roman Catholic diocese of East Anglia website.

- ↑ English Benedictine Congregation – Douai Abbey.

- ↑ Polack, Bernard; Whitbourn, John (1999). The Catholic Parish of St Edmund King & Martyr, Godalming, 1899–1999. Farnham: Arrow Press. p. 8.

- ↑ "St Edmund, Patron Saint of Suffolk". St Edmund's day feature. BBC. 2007-04-25. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ↑ "Drive to reinstate 'local lad' St Edmund as country's patron saint". Bury Free Press. 2013-06-07. Retrieved 2013-06-07.

- ↑ "St Edmund takes on St George for England's patron saint honour". BBC. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ John Lydgate's Metrical Lives of Saints Edmund and Fremund This can be viewed at the British Library's Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts website.

- ↑ http://www.history.ac.uk/richardII/wilton.html 'The Wilton Diptych', in the Richard II's Treasure website.

- ↑ Frantzen, Bloody Good, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Churches with surviving wall paintings of Edmund can be found at Medieval Wall Painting in the English Parish Church website: D to F.

- ↑ Field, Christianity and Romance, p. 140.

References

- Abbo of Fleury. (0945-1004- Abbo Floriacensis Abbas\ - Operum Omnium Conspectus seu 'Index of available Writings' apud www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu): Passio Sancti Edmundi Regis Et Martyris (The Latin text of Abbo's work: the martyrdom is described in Chapter X).

- Ælfric of Eynsham. "The Martyrdom of St. Edmund, King of East Anglia, 870". Paraphrase of Abbo of Fleury's Life of St. Edmund. Mediaeval Sourcebook. (Modern English translation of Ælfric's Old English Paraphrase loosely based on Abbo's work).

- Altmann, Barbara K. (2003). The Court Reconvenes: Courtly Literature Across the Disciplines. Woodbridge: Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-797-1.

- Ball, Ann (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Catholic Devotion and Practices. Huntingdon, USA: Our Sunday Visitor Inc. ISBN 0-87973-910-X.

- "Edmund the Martyr, Saint". The Catholic Encyclopedia: Volume 5. Internet Archive. 1913. p. 294. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- "The Basilica of St Saturnin". The Catholic World: A Monthly Magazine of General Literature and Science. New York: The Catholic Publication House. VIII (October 1868 – March 1869).

- Cantor, Leonard, ed. (1982). The English Medieval Landscape. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-0707-9.

- Earle, John (1865). Two of the Saxon Chronicles Parallel (in Old English). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860949-3.

- Field, Rosalind; Brewer, Derek (2010). Christianity and Romance in Medieval England. Christianity and Culture. Woodbridge: Brewer. ISBN 1-84384-219-X.

- Frantzen, Allen J. (2004). Bloody Good: Chivalry, Sacrifice, and the Great War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-26085-3.

- Gransden, Antonia (1992). Legends, Traditions and History in Medieval England. London, Rio Grande: Hambleton Press. ISBN 1-85285-016-7.

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark (1986). Medieval European Coinage 1. The Early Middle Ages (5th–10th centuries). Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-26009-4.

- Hanks, Patrick; Hardcastle, Kate; Hodges, Flavia (2006), A Dictionary of First Names, Oxford Paperback Reference (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 84, ISBN 978-0-19-861060-1

- Hervey, Lord Francis (1907). Corolla Sancti Eadmundi. The Garland of Saint Edmund, King and Martyr. London. p. 672.

- Houghton, Bryan (1970). Saint Edmund king and Martyr. Lavenham & Sudbury, Suffolk: Terence Dalton Limited. ISBN 9780900963186.

- Kennedy, John J (Autumn 1991). "The Arms of Ireland: Medieval and Modern". Coat of Arms. The Heraldry Society (155). Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Mawer, Allen (1910). "Edmund, King of East Anglia". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- Mostert, Marco (1999). "Edmund, St, King of East Anglia". In M. Lapidge; et al. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. London: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-22492-0.

- Nicolas, Sir Harris (1832). History of the Battle of Agincourt. London: Johnson.

- Plunkett, Steven (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3139-0.

- Preble, George Henry (1917). Origin and History of the American Flag and of the Naval and Yacht-Club Signals, Seals and Arms, and Principal National Songs of the United States, with a Chronicle of the Symbols, Standards, Banners, and Flags of Ancient and Modern Nations. Philadelphia: N. L. Brown.

- Ridyard, Susan J. (1988). The Royal Saints of Anglo-Saxon England: a Study of West Saxon & East Anglian Cults. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30772-4.

- Stead, Ian Mathieson; Bourke, J.; Brothwell, D. (1986). Lindow Man: The Body in the Bog. London: British Museum. ISBN 0-7141-1386-7.

- Swanton, Michael (1997). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92129-5.

- Warner, Peter (1996). The Origins of Suffolk. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-3817-0.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

- Yorke, Barbara (1995). Wessex in the Early Middle Ages. New York: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1314-2.

Further reading

- Bale, Anthony, ed. (2009). St Edmund, King and Martyr: Changing Images of a Medieval Saint. York, USA: York Medieval Press. ISBN 1-903153-26-3.

- Briggs, Keith (2011). "Was Hægelisdun in Essex? A new site for the martyrdom of Edmund". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History. Suffolk Institute of Archaeology. XLII (3): 277–291.

- Butler, Alban; Sarah Fawcett Thomas; Paul Burns (1997). Butler's Lives of the Saints – November. Collegeville: The Liturgical Press. pp. 173–175. ISBN 0-8146-2387-5.

- Hervey, Francis (1907). Corolla Sancti Eadmundi (The Garland of St Edmund, King and Martyr). London: J. Murray.

- Mackinlay, James Boniface (1893). Saint Edmund: King and Martyr. New York: Art and Book Company.

- Taylor, Mark (2013). Edmund: The Untold Story of the Martyr-King and His Kingdom. Fordaro. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-9927211-0-7.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1969). "Fact and Fiction in the Legend of St Edmund". Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology. 31: 217–233.

External links

- Edmund 6 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England

- An account of Edmund's legendary life and his veneration in mediaeval times at the St Edmundsbury Borough Council website.

- Saint Edmund: "England's Original Patron Saint", at Hoxne's website.

- Other examples of illuminated manuscripts depicting Edmund, from the British Library:

- - Harley 1766 (The Fall of Princes)

- - Royal 2 B VI (Psalter and Canticles 13th century)

- Saint Edmund at the Christian Iconography web site

- Here Followeth The Life of S. Edmund in Caxton's translation of the Golden Legend

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| English royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Æthelweard |

King of East Anglia 25 December 855 (trad.) – 20 November 869 |

Succeeded by Oswald |