Education in Ghana

| |

| Ministry of Education Ministry of Higher Education | |

|---|---|

| National education budget (2010) | |

| Budget | 23 % of government expenditure[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English |

| System type | National |

| Literacy (2010) | |

| Total | 71.5 |

| Male | 78.3 |

| Female | 65.3 |

| Enrollment (2012/2013[2]) | |

| Total | 8,329,177 |

| Primary | Pre-primary: 1,604,505, Primary: 4,105,913, JHS: 1,452,585 |

| Secondary | SHS and TVI: 904,212 |

| Post secondary | 261,962 (including universities: 109,278)‡ |

| ‡: statistics for 2011/2012 | |

Education in Ghana was mainly informal, and based on apprenticeship before the arrival of European settlers, who built a formal education system addressed to the elites. With the independence of Ghana in 1957, universal education became an important political objective. The magnitude of the task as well as economic difficulties and political instabilities have slowed down attempted reforms. The Education Act in 1987, followed by the Constitution of 1992, gave a new impulse to educational policies in the country. In 2011, the primary school net enrollment rate was 84%, described by UNICEF as "far ahead" of the Sub-Saharan average. In its 2013-14 report, the World Economic Forum ranked Ghana 46th out of 148 countries for education system quality. In 2010, Ghana's literacy rate was 71.5%, with a notable gap between men (78.3%) and women (65.3%). Theguardian newspaper disclosed in April 2015 that 90% of children in Ghana were enrolled in school, ahead of countries like Pakistan and Nigeria at 72% and 64% respectively.[3]

Education indicators in Ghana reflect a gender gap and disparities between rural and urban areas, as well as between southern and northern parts of the country. Those disparities drive public action against illiteracy and inequities in access to education. Eliminating illiteracy has been a constant objective of Ghanaian education policies for the last 40 years; the difficulties around ensuring equitable access to education is likewise acknowledged by the authorities. Public action in both domains has yielded results judged significant but not sufficient by national experts and international organizations. Increasing the place of vocational education and training and of ICT (information and communications technology) within the education system are other clear objectives of Ghanaian policies in education. The impact of public action remains hard to assess in these fields due to recent implementation or lack of data.

The Ministry of Education is responsible for the administration and the coordination of public action regarding Education. Its multiple agencies handle the concrete implementation of policies, in cooperation with the local authorities (10 regional and 138 district offices). The State also manages the training of teachers. Many private and public colleges prepare applicants to pass the teacher certification exam to teach at the primary level. Two universities offer special curricula leading to secondary education teacher certification. Education represented 23% of the state expenditure in 2010; international donor support to the sector has steadily declined as the State has taken on the bulk of education funding.

Education in Ghana is divided into three phases: basic education (kindergarten, primary school, lower secondary school), secondary education (upper secondary school, technical and vocational education) and tertiary education (universities, polytechnics and colleges). Education is compulsory between the ages of four and 15 (basic education). The language of instruction is mainly English. The academic year usually runs from August to May inclusive.[4]

History

In precolonial times, education in Ghana was informal. Knowledge and competencies were transmitted orally and through apprenticeships.[5] The arrival of European settlers during the 16th century brought new forms of learning; formal schools appeared, providing a book-based education.[5] Their audience was mainly made up of local elites (mulattos, sons of local chiefs and wealthy traders) and their presence was limited to the colonial forts, long confined to the coasts.[6] The 19th century saw the increasing influence of Great Britain over the Ghanaian territories that led to the establishment of the Gold Coast Colony in 1874.[7] With it came a growing number of mission schools and merchant companies, the Wesleyan and the Basel missions being the most present .[8] The Wesleyan mission stayed on the coasts with English as main language. The Basel mission expanded deeper inland and used vernacular languages as the medium of proselytizing.[8] With the support of the British government, missions flourished in a heavily decentralized system that left considerable room for pedagogical freedom. Missions remained the main provider of formal education until independence.[6] Under colonial rule, formal education remained the privilege of the few.[8]

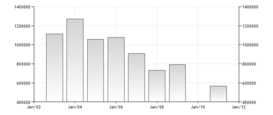

Ghana obtained its independence in 1957. The new government of Nkrumah described education as the key to the future and announced a high level university providing an "African point of view", backed by a free universal basic education.[9] In 1961, the Education Act introduced the principle of free and compulsory primary education and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology was established.[10][11] As a result, the enrollment almost doubled the next year.[12] This sudden expansion was, however, hard to handle; Ghana quickly fell short of trained teachers[13] and the quality of the curriculum (lacks in English or in Mathematics) was put into question.[12] The fall of Nkrumah in 1966 was followed by stronger criticisms toward the expansion of education at the cost of quality.[9] Despite the rapid increase of school infrastructures, the enrollment slowly declined until 1973.[12] The year 1974 saw attempts of reforms. Based on the “Dozbo committee report”, they followed 2 goals: reducing the length of pre-tertiary education (The structure primary school/Junior High School/Senior High school was created)[14] and modifying programs in order to promote more practical contents at school.[5][12] Those reforms were, however, very partially implemented due to financial limitations and political instability.[5][12][14] The economic situation of the country worsened at the beginning of the 80's.[9][14] Into an economic downturn, the country was failing at solving the deficit of teachers, maintaining the infrastructures and convincing the parents to bet on school instead of a paid work.[12][15] Gross Enrolment Ratio(GER) dropped sharper in response, falling below 70% in 1985.[12]

The year 1987 marked the beginning of new series of reforms: The military coup of Jerry Rawlings in 1981 had been followed by a period of relative political stability and opened the way to broader international support.[9] The Rawlings government had gathered enough founds from numerous international organizations (including the World bank) and countries to afford massive changes to the educational system.[14] The 1987 Education Act aimed at turning the 1974’s Dozbo committee measures into reality:[14] a national literacy campaign was launched,[15] pre-tertiary education was reduced from 17 to 12 years and vocational education appeared in Junior High School.[14] Education was made compulsory from 6 to 14. The reform succeeded in imposing a new education structure, as well as to increase the enrollment and the number of infrastructure.[16] Yet the promise of universal access to basic education was not fulfilled.[17] Vocational programs were also considered as a failure.[16] The return to constitutional rule in 1992, though still under Rawlings government, gave a new impulse by reclaiming the duty of the state to provide a free and compulsory basic education for all.[18] The local government Act of 1993 initiated the decentralization in education administration, by transferring power to district assemblies.[18] The Free, Compulsory and Universal Basic Education(FCUBE) provided an action plan for the period 1996-2005, focusing on bridging the gender gap in primary-school, improving teaching materials and teacher’s living condition.[14] It was later completed by significant acts, like the creation of the “Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training” in order to promote vocational education(2006), or the founding of the national accreditation board (2007), introducing a national accreditation for all tertiary level institution.[18] In 2007-2008, the two years in Kindergarten were added to the free and compulsory education (which is now going age 4 to 14).[18]

| x | 1968(public sector only)[19][20] | 1988[19] | 2001[21] | 2007[22] | 2012[23] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pupils | 1,397,026 | x | 4,154,374 | 5,024,944 | 7,465,208 |

| Teachers | 47,880 | 97,920 | 155,879 | 229,144 | 268,619 |

| Schools | x | x | 32,501 | 46,610 | 56,919 |

Statistics

Ghana's spending on education has been around 25 %[1] of its annual budget in the past decade.

The Ghanaian education system from Kindergarten up to an undergraduate degree level takes 20 years.[24][25]

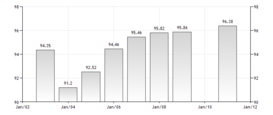

The ratio of females to males in the total education system was 96.38% in 2011.[26] The adult literacy rate in Ghana was 71.5% in 2010, with males at 78.3% and females at 65.3%.[27] The youth female and male ages 15–24 years literacy rate in Ghana was 81% in 2010, with males at 82%,[28] and females at 80%.[29]

Since 2008, enrollment has continually increased at all level of education (pre-primary, primary, secondary and tertiary education).[30] With 84% of its children in primary school, Ghana has a school enrollment "far ahead" of its sub-saharian neighbor's.[31] The number of infrastructures has increased consequently on the same period.[32] Vocational Education (in "TVET institutes", not-including SHS vocational and technical programs) is the only exception, with an enrollment decrease of 1,3% and the disappearance of more than 50 institutions between the years 2011/12 and 2012/2013.[33] This drop would be the result of the low prestige of Vocational Education and the lack of demand from industry.[34]

| x | KG | Prim | JHS | SHS | TVET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment | 1,604,505 | 4,105,913 | 1,452,585 | 842,587 | 61,496 |

| GER in % | 113.8 | 105.0 | 82.2 | 36.8 | 2.7 |

| x | KG | Prim | JHS | SHS | TVET |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public | 13,305 | 14,112 | 8,818 | 535 | 107 |

| Private | 5,972 | 5,742 | 3,618 | 293 | 74 |

| Total | 19,277 | 19,854 | 12,436 | 828 | 181 |

In 2011/2012, tertiary education gathers 261,962 students:[37] 202,063 in the public sector and 59,899 in the private sector, divided in 142 tertiary institutions[37]

In 2011, the primary school net enrolment rate is of 84% and described by UNICEF as "far ahead" of the Sub-Saharan average.[38] In its 2013-14 report, the World Economic Forum ranked Ghana 46th out of 148 countries regarding the education system quality.[39]

Structure of formal education

Overview

The Ghanaian education system is divided in three parts: "Basic Education", secondary cycle and tertiary Education. "Basic Education" lasts 11 years(Age 4-15), is free and compulsory.[40] It is divided into Kindergarten(2 years), primary school(2 modules of 3 years) and Junior High school(3 years). The junior high school(JHS) ends on the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE).[40][41] Once the BECE achieved, the pupil can pursue into secondary cycle.[42] Secondary cycle can be either general (assumed by Senior High School) or vocational(assumed by technical Senior High School, Technical and vocational Institutes and a massive private and informal offer). Senior High school lasts three years and ends on the West African Secondary School Certificate Examination (WASSCE). Other secondary institutions leads to various certifications and diplomas. Tertiary education is basically divided into university (academic education) and Polytechnics(vocational education). The WASSCE is needed to join a university bachelor's degree program.[43]A bachelor's degree lasts 4 years and can be followed by a 1 or 2 year Master. The student is then free to start a Phd, usually completed in 3 years.[44] Polytechnics are opened to vocational students, from SHS or from TVI.[45] A Polytechnic curriculum lasts 2 to 3 years.[45] Ghana also possesses numerous colleges of education.[46] New tertiary education graduates have to serve one year within the National Service Scheme.[47][48] The Ghanaian education system from Kindergarten up to an undergraduate degree level takes 20 years.[49]

The academic year usually goes from August to May inclusive.[4] The school year lasts 40 weeks in Primary school and SHS, and 45 weeks in JHS.[50]

Basic Education

Basic Education lasts 11 years.[40] The curriculum is free and compulsory (Age 4-15) and is defined as "the minimum period of schooling needed to ensure that children acquire basic literacy, numeracy and problem solving skills as well as skills for creativity and healthy living".[40] It is divided into Kindergarten, Primary school and Junior High School (JHS), which ends on the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE).[42]

Kindergarten lasts 2 years (Age 4-6).[40] The program is divided in 6 core areas:[40] Language and Literacy (Language Development), Creative Activities (Drawing and Writing), Mathematics (Number Work), Environmental Studies, Movement and Drama (Music and Dance), and Physical Development (Physical Education)

Primary school lasts 6 years (Age 6-11).[40] The courses taught at the primary or basic school level include English, Ghanaian languages and Ghanaian culture, ICT, mathematics, environmental studies, social studies, Mandarin and French as an OIF associated-member; integrated or general science, pre-vocational skills and pre-technical skills, religious and moral education, and physical activities such as Ghanaian music and dance, and physical education. There is no certificate of completion at the end of primary school.[4]

Junior Secondary School lasts 3 years(Age 12-15).[41] The Junior High School ends on the Basic Education Certificate(BECE), which covers the following subjects:English Language, Ghanaian Language and Culture, Social Studies, Integrated Science, Mathematics, Basic, Design and Technology, Information and Communication Technology, French (optional), Religious and Moral Education.[42]

Secondary cycle

Students who pass the BECE can proceed into secondary education, general or vocational.

The secondary general education is assumed by the Senior High School(SHS). The SHS curriculum is composed of core subjects, completed by elective subjects(chosen by the students). The core subjects are English language, mathematics, integrated science (including science, ICT and environmental studies) and social studies (economics, geography, history and government).[49] The students then choose 3 or 4 elective subjects from 5 available programmes: agriculture programme, general programme (divided in 2 options: arts or science), business programme, vocational programme and technical programme.[49][51]

The Senior high school's curriculum lasts 3 years, as a result of numerous reforms: Originally a three years curriculum, it was extended to 4 years in 2007.[52] However, early 2009 this reform was making SHS a 3 years curriculum again.[53] The length of the SHS is still a disputed question.[54][55]

The SHS ends on a final exam called the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE), formerly called Senior Secondary School Certificate (SSSC) before 2007.[56] A SHS ranking is established every year by the Statistics, Research, Information, Management and Public Relations (SRIMPR) division of the ministry of Education, based on the WASSCE results.[57]

Vocational and technical Education (also called “TVET”) takes different forms. After obtaining the BECE, students who wish to pursue in vocational Education have two main possibilities: Following the vocational and technical programs as elective courses in a SHS, or joining a technical and vocational institute(TVI).[45] SHS students follow the usual SHS 3 year curriculum. They can then – provided sufficient results at the WASSCE – join a university or polytechnic program.[45][58] TVI students usually follow a 4-year curriculum, divided in two cycles of two years, leading to “awards from City & Guilds, the Royal Society of Arts or the West African Examinations Council".[58] They can then pursue into a polytechnic program.[45] The state of vocational education sector remains however obscure in Ghana: 90% of the vocational education is still informal, taking the form of apprenticeship.[58] The offer of formal vocational education within the private sector is also hard to define[33] and the Ministry of Education recognizes its incapacity to give a clear overview of the public vocational education, many ministries having their own programs.[33]

International schools also exists in Ghana: the Takoradi International School, Tema International School, Galaxy International School, The Roman Ridge School, Lincoln Community School, Faith Montessori School, American International School, Association International School, New Nation School, SOS Hermann Gmeiner International College and International Community School, which offer the International Baccalaureat, Advanced Level General Certificate of Education and the International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE).[24]

Tertiary education

_North_Campus.jpg)

Tertiary education in Ghana has been notably growing during the last twenty years, both in terms of enrollment and infrastructures.[46] A substantial part of this development come from the private sector.[46][59][60][61]

Universities(6 public and 49 private institutions)[46] offer an academic education, from bachelor to Phd. Students are admitted based on their performance at the W.A.S.S.C.E (West African Senior School Certificate Examination"): A maximum of 24 points is generally required in order to apply to a Bachelor degree program(see Grading system in Ghana). A bachelor degree is usually completed after four years of majoring in a specific field of interest.[62] Master degrees are of two sorts: A one year program, concluded with a final paper based on a literature study, or a two year program, concluded with a final paper based on one year of independent research.[62] Both can lead to a Phd, usually achieved in 3 years within a doctoral programme.[62]

Polytechnics (10 institutions)[46] offer a vocational education. They propose 3-year curricula, leading to a Higher National Diploma(HND). The students have then the possibility to follow a special 18 month program to achieve a Bachelor of Technology degree.[45]

Ghana also possesses many "colleges of education", public or private.[46] They are usually specialized in one field (colleges of agriculture p.e) or in one work-training (Nursing training colleges, teacher training colleges, p.e).[46]

New tertiary education graduates have to serve one year within the National Service. Participants can serve in one of the eight following sectors: Agriculture, Health, Education, Local Government, Rural Development, Military and Youth Programmes[47][48]

Grading system

Ghana’s grading system is different at every point in education. Through the kindergarten to the junior high, every grade a student gains is written in terms of numbers instead of alphabets. There is no system of pluses and minuses (no "1+"’s or "6+"’s as grades).

Senior high school

Until 2007, Senior secondary High school ended with the Senior Secondary School Certificate(SSSC).[50] Its grading system went from A to E.[56] In 2007, the SSSC was replaced by the West African Secondary School Certificate Examination (WASSCE).[50] The WASSCE grading system adds numbers to the letters, offering a larger scale of evaluation. In both systems, each grade refers to a certain number of points. In order to join a Bachelor degree program, applicants are usually asked not to exceed 24 points at their WASSCE/SSSC.[56]

| SSSCE grades(before 2007), [in points] | WASSCE grades(since 2007),[in points] | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A[1] | A1[1] | Excellent |

| B[2] | B2[2] | Very good |

| C[3] | B3[3] | Good |

| D[4] | C4[4] | Credit |

| x | C5[5] | Credit |

| x | C6[6] | Credit |

| E | D7 | Pass |

| x | E8 | Pass |

| F | F9 | Fail |

Tertiary education

The grading system varies depending of the institution.[56] Almost all the tertiary institutions are based on the Grade Point Average (G.P.A) as a way of assessing whether a student is failing or passing. But individual schools have their own way of calculating GPA's, because of their individualized marking schemes. For example, a mark of 80 may be an A in a school, but may be an A+ in another school.

Governance

Administration

Education in Ghana is under the responsibility of the ministry of Education. Implementation of policies is assumed by its numerous agencies: The Ghana Education Service (GES) is responsible for the coordination of national education policy on pre-tertiary education.[18] It shares this task with three autonomous bodies, the National Inspectorate Board (NIB), the National Teaching Council (NTC) and the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA).[63] The terminal examinations of the pre-tertiary education are conducted by the West African Examination Council (National Office, Ghana): it includes the BECE and the WASCCE but also foreign professional examination.[64] The Council for Technical and vocational education and Training is dedicated to the management of TVET.[45] The collection and analysis of educational data is handled by the Education Management Information System (EMIS).[18]

Policies are implemented in cooperation with the local offices: Ghana is divided in 10 regional and 138 local offices.[18] The Ghana Education Decentralization Project (GEDP), launched in 2010 and ended in 2012, has increased the influence of local authorities over management, finance and operational issues when it comes to educational matters.[63]

Financing

The Ghanaian State has dedicated 23% of its expenditure into education in 2010.[65] More than 90% of this budget is spent by the Ministry of Education and its agencies: Primary education (31% of the expenditure) and tertiary education(21,6%) are the most provided.[65] The expenditures are partly funded by donors. Among them can be found the World Bank, the United States (through the USAID), the United Kingdom(through the DfID) and the European Union.[66] Their participation is usually project-focused and granted under certain condition, giving them a certain influence.[66] This influence can provoke debates when it comes to key-reforms:[66] For the FCUBE project, the World Bank imposed book charges in primary schools and reduced feeding and boarding costs in secondary schools. Facing criticisms, the Bank insisted on the “strong domestic ownership” of the reform and the necessity to ensure “cost recovery”.[66] Between 2005 and 2012, the part of donors in the Ghanaian budget has fallen from 8.5 to 2.5% of the total education expenditure.[65]

Teacher training

Colleges of Education are the main teacher training institutions: There are 38 public and 3 private "CoE" split in then 10 Ghanaian regions.[67] They offer a three-year curriculum that leads to the Diploma in Basic Education(DBE).[67] The education is described as “uniform” and with a “national focus” even if CoE are present in every Ghanaian regions.[67] The final examinations granting the DBE are conducted by the public University of Cape Coast’s Institute of Education.[67] The holders of the DBE are allowed to teach at every level of the Basic education(Kindergarten, Primary school, Junior secondary School).[67]

Apart from the Colleges of education, two universities (Cape Coast and Winneba) train teachers. A specific four-year bachelor's degree allows to teach in any pre-tertiary education (most graduates choosing secondary education).[68] A specific master's degree is needed for teaching in CoE.[67] Universities also offer to DBE graduate a two-curriculum granting the right to teach in secondary education.[67]

Distance education is also possible: the programme lasts four years and leads to the Untrained Teacher’s Diploma in Basic Education (UTDBE).[67] It was introduced to increase the number of basic education teachers in rural area. Serving teacher can also benefit of continuing education (in-service training, cluster).[67]

Public action and Policies

Adult literacy, non-formal education

Public action against illiteracy started more than 50 years ago in Ghana. Initiated in the 1940s by the British rulers, its eradication was raised to top-priority at the independence in 1957.[69] Political unrests however limited political actions to sporadic short-term programmes, until 1987 and the creation of the Non-Formal Education Division (NFED), whose goal was to eliminate illiteracy by 2000.[69] After a convincing try in 2 regions, the Functional Literacy Skills Project (FLSP) was expanded to the whole country in 1992. In 2000, the programme was taken over by the National Functional Literacy Programme (FNLP), which is still active nowadays.[69] Those programmes focus on gender and geographical inequalities. Women and people living in rural area are their main targets.[70] In 2004, there were 1238 “Literacy centers”, situated mostly in non-urban area.[70]

The successive projects led to statistical progresses.[70] In 1997, 64% of women were illiterate for 38% of men, for a global literacy rate of 54%.[69] In 2010, women literacy was of 65% and the global literacy rate had increased to 71.5%.[27] Academics however pointed out the insufficient progress of women literacy and the difficulty for graduated to upkeep their new skills.[70]

| x | Adult literacy(15+) | Youth literacy (15-24) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av | M | F | Av | M | F | |

| 2000 | 57.9 | 66.4 | 49.8 | 70.7 | 75.9 | 65.4 |

| 2010 | 71.5 | 78.3 | 65.3 | 85.7 | 88.3 | 83.2 |

| 2015(projection) | 76.3 | 81.5 | 71.0 | 90.6 | 91.3 | 89.9 |

Other forms of non-formal education are also conducted by the NFED: "Life-skills training" (Family planning, hygiene, prevention on AIDS) targeting adolescent and young mother, "Occupational skills training" for unemployed adults or "civil awareness" seminars (on civil rights and duties) addressed to illiterate adults.[70]

Development of technical and vocational education

Developing technical and vocational education and training(TVET) is considered a priority by central authorities in order to tackle poverty and unemployment.[72][73]

TVET in Ghana face numerous problems: low completion rate (in 2011, 1.6% of the population got a TVET degree whereas 11% of the population followed a TVET programme),[72] « poorly trained instructor » and lack of infrastructure.[73] The Ghanaian industry also criticizes the lack of practical experience of the formal graduates and the lack of basic skills(reading, writing) of informal apprentices.[72] In 2008, the OECD reproached the opacity of the qualifications framework and the multiplication of worthless TVET certificates.[73] The official council for TVET observed that informal or graduated TVET students struggle to find a job, and then have to deal with income volatility or low wages.[72] TVET therefore suffer of a poor reputation among students, parents and employers.[72][74]

In 2005, a micro-credit system in favor of low-skilled unemployed youth was implemented(STEP programme).[73] In 2006, the Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training(COTVET) was created and entrusted with the mission of coordination "TVET policies" in Ghana.[45] The council introduced a National Youth Found in 2006, and proposed a TVET qualifications framework in 2010.[72] It tries besides to frame the informal sector through a National Apprenticeship Programme(NAP)[45] and to strengthen guidance and counselling at basic education level.[75]

Impacts are, however, difficult to assess :[33] TVET in Ghana is still hard to grasp. 90% is informal[72] and both the public and private sectors are highly segmented.[33][73] The ministry of Education itself admits its incapacity to provide a global statistic view of the TVET sector in Ghana.[33]

Equity in access to tertiary education

With the rise of enrollment in secondary education, competition for joining higher education institution has globally increased: In 2001, the university of Ghana had admitted 96% of the relevant applications it had received. In 2011, this acceptance rate had fallen to 52%.[76] This increasing selectivity highlights inequalities in Ghana regarding Education: Being a woman[77] or living in a rural area[78][79] can reduce the chance of reaching tertiary Education. Socioeconomic status is also a factor of exclusion, as studying at the highest level is expensive: Public universities have no tuition fee but usually demand payment for other charges: registration fee, technology fee, examination fee, academic facility user fee, medical services fee.[80] These charges can lead to self-censorship behaviors, some students choosing, for instance, Teacher Training Colleges (where students can receive stipends) instead of joining a university.[80]

Policies has been developed to limit those inequalities: Some universities have, for instance, lowered their minimum entry requirement or created scholarship for students from the "less-endowed secondary school".[81][82] A "Girls Education unit" has been created by the government within the Ghana Education Service, in order to reduce gender-biased disparities: The unit tries to tackle the problem at its source, focusing on the "basic Education" to avoid high female school drop-out from JHS to SHS.[83] Progresses have been made: The proportion of girls in Higher Education has increased from 25%(1999) to 32%(2005).[84]Yet gender still generates inequality, for numerous reasons: Hostile school environment, priority given to the boys in poor families, perpetuation of "gender roles" ("a woman belongs to the household"), early customary marriages, teenage pregnancy...[84]

The higher Education is still mostly occupied by a small male elite:

HE in Ghana is disproportionately ‘consumed’ by the richest 20% of the population. Male students from the highest income quintile (Q5) are more than seven times more likely to enter and successfully complete HE than those from the poorest quintile (Q1). The situation is even more precarious for the female category where students come from only the richest 40% of the population.

ICT in education

Computer technology used for teaching and learning began to receive governments’ attention in the past decade. The ICT in Education Policy of Ghana requires the use of ICT for teaching and learning at all levels of the education system. Attempts have been made by the Ministry of Education to support institutions in teaching of ICT literacy. Most secondary, and some basic, schools have computer laboratories.[85] Despite the interest in ICT, computers are very limited and are often carried around to insure that they do not get stolen.[86]

A recent study on Pedagogical integration of ICTs from 2009-2011 in 10 Ghanaian schools indicates that there is a gap between the policy directives and actual practices in schools. The emphasis of the official curricula is on the development of students’ skills in operating ICTs but not necessarily using the technology as a means of learning subjects other than ICTs. The study also found that the ministry of Education is currently at the stage of deployment of ICT resources for developing the needed ICT literacy required for integration into teaching/learning.[85]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Public spending on education, total (% of government expenditure)". worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, pages 9-12; table 46 (p. 78).

- ↑ Rustin, Susanna (7 April 2015). "Almost 90% of Ghana's children are now in school". Theguardian.com. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- 1 2 3 NUFFIC 2013, pp. 4-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Joe Adu-Agyem; Patrick Osei-Poku (November 2012). "Quality Education In Ghana: The Way Forward". International Journal of Innovative Research and Development. pp. 165–166. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 Denis Cogneau; Alexander Moradi (November 2012). "Borders that divide: Education and religion in Ghana and Togo since colonial times" (PDF). The African Economic History Network. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ghana, a country study" (PDF). Federal Research Division Library of Congress. November 1994. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 C.K. Graham (1971). "The History of Education in Ghana: From the earliest time to the declaration of independance". F. Cass. pp. 181–185.

- 1 2 3 4 Kwame Akyeampong. "Educational Expansion and Access in Ghana: A Review of 50 Years of Challenge and Progress" (PDF). Centre for International Education, University of Sussex. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Ghana Education Service (GES) (2004). "The development of Education, National report of Ghana" (PDF). UNESCO-IBE. p. 2. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ Daniel, G. F (1997–1998). "The universities in Ghana". The Commonwealth Universities Year Book. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Abena D. Oduro (2000). "Basic Education in Ghana in the post-reform period". Center for Policy Analysis (CEPA).

- ↑ "International Year Book of Education" (PDF). UNESCO-IBE. 1969. p. 79. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nii Moi Thompson; Leslie Casely-Hayford. "The financing and outcomes of Education in Ghana" (PDF). University of Cambridge. pp. 9–14. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 John Macbeath (October 2010). "Living with the colonial legacy: The Ghana story" (PDF). Center for Common Wealth Education. p. 2. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 Nii Moi Thompson; Leslie Casely-Hayford. "The financing and outcomes of Education in Ghana" (PDF). University of Cambridge. p. 26. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ↑ Joshua J.K. Baku, ERNWACA (2003). "Critical Perspectives on Education and skills in eastern Africa on basic and post-basic Levels". NORRAG. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "World Data on Education" (PDF). UNESCO-IBE. September 2010. p. 3. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 D. K. Mereku (2000). "Demand and supply of basic school teachers in Ghana" (PDF). University College of Education of Winneba. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Abena D. Oduro (2000). "Basic education in Ghana in the post-reform period" (PDF). Centre for Policy Analysis, Accra. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "National Profile - 2001 / 2002 School Year Data" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Ghana. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "National Profile - 2007 / 2008 School Year Data" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Ghana. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "National Profile - 2012 / 2013 School Year Data" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Ghana. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- 1 2 "Education in Ghana" ghanaweb.com

- ↑ "What to know about the National Accreditation Board (NAB)". NAB.gov.gh. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ↑ "Ratio of girls to boys in primary and secondary education (%)". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- 1 2 Field Listing: Literacy.cia.gov. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Literacy rate, youth male (% of males ages 15-24)". worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ "Literacy rate, youth female (% of females ages 15-24)". worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, Table (p. 9), Table 6 (p. 30), Table 46 (p. 48).

- ↑ "UNICEF – Basic Education and Gender Equality" (PDF). unicef.org. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, Table 2 (p. 25), Table 4 (p. 27), Table 6 (p. 30), Table 26 (p. 55).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ministry of Education 2013, p. 65.

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, Table (p. 9), Table 6 (p. 30).

- ↑ Ministry of Education 2013, Table 2 (p. 25), Table 4 (p. 27), Table 6 (p. 30), Table 26(p. 55).

- 1 2 Ministry of Education 2013, Table 46 (p. 78).

- ↑ "Fact sheet, Education in Ghana" (PDF). UNICEF. October 2012. p. 1, table comparing sub-sahara to Ghana. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ↑ "Global competitiveness report" (PDF). World Economic Forum. 2014. p. 196. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Basic Education curriculum". Ghana Education Service (GES). Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Basic curriculum Education: The Junior High Education". Ghana Education Service. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 West African Examinations Council(corporate site: Ghana). "BECE". Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ NUFFIC 2013, p. 7.

- ↑ NUFFIC 2013, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Vocational Education in Ghana". UNESCO-UNEVOC. July 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Atuahene, Ansah 2013, p. 2.

- 1 2 "Country profile: Ghana" (PDF). International Association for National Youth Service. 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- 1 2 "Mandate of the NSS". National Service Scheme (NSS). Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "A Brief History of the Ghanaian Educational System". TobeWorldwide.org. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09.

- 1 2 3 NUFFIC 2013, p. 5.

- ↑ West African Examinations Council (WAEC) (2012). "WASSCE - subjects for examination". Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ Modern Ghana. "The 2007 education Reform and its challenges". Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Ghanaweb (2 September 2009). "3-year SHS programme starts next year". Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ TV3 Network. "Bring back the 4 year SHS system". Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- ↑ Ghana Web (5 June 2013). "The fate of Ghana's Education system". Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 NUFFIC 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ Expose Ghana (March 2014). "2013 WASSCE SHS Rankings- Full List". Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 "From prejudice to prestige: Vocational education and training in Ghana" (PDF). Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (COTVET). 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- ↑ "The development of Education: National report of Ghana" (PDF). IBE. 2004. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ "Ghana private tertiary institutions offering degree program" Retrieved 2 January 2011.

- ↑ "Private Colleges of Education". National Accreditation Board (NAB). Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 NUFFIC 2013, pp. 9-10.

- 1 2 "Ghana Education Decentralization Project (GEDP): Operational Framework for National Teaching Council (NTC)" (PDF). Ministry of Education. February 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "About the WASSCE". WASSCE. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Education Finance Brief, Ghana". Ministry of Education. November 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Nii Moi Thompson; Leslie Casely-Hayford. "The financing and outcomes of Education in Ghana" (PDF). University of Cambridge. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kwame Bediako Asare; Seth Kofi Nti (April 2014). "Teacher Education in Ghana: A contemporary synopsis and matters arising" (PDF). SageOpen. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Research overview: Teacher preparation and continuing professional development in Africa (TPA)". University of Sussex. 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "National Functional Literacy Programme (NFLP)" (PDF). Overseas Development Institute. 2005. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Francis Owusu-Mensah (2008). "Ghana non-formal Education" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ↑ "Adult and youth literacy: National, regional and global trends, 1985-2015" (PDF). UNESCO-UIS. June 2013. p. 51 (Table 6). Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "From prejudice to prestige: Vocational education and training in Ghana" (PDF). Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (COTVET). 2011. pp. 19–35. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ghana country profile" (PDF). OECD. 2008. pp. 341–342. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Adam Dasmani. "Challenges facing technical institute graduates in practical skills acquisition in the upper East region of Ghana" (PDF). Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education (APJCE). p. 2. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "Skills advocate: Quarterly COTVET newsletter" (PDF). COTVET. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Atuahene, Ansah 2013, fig. 1 (p. 3).

- ↑ Atuahene, Ansah 2013, p. fig. 3(p. 4).

- ↑ Manuh T.; Sulley G.; Budu J. (2007). Change and transformation in Ghana’s publicly funded universities. Partnership for Higher Education in Africa (PDF). Oxford, UK: James Currey and Accra.

- ↑ "Addae-Mensah says inequalities in basic education system is dangerous". Modern Ghana. 23 February 2000. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 Atuahene, Ansah 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ "University of Ghana to admit students from less endowed SSS". Ghana Web. March 2004. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ "KNUST implements scheme for admitting students from less endowed schools". August 2003. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ "Girl's Education". Ghana Education Service. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- 1 2 Atuahene, Ansah 2013, pp. 5-6.

- 1 2 K. D. Mereku, I. Yidana, W. H. K. HORDZI, I. Tete-Mensah; Williams, J. B. (2009). Pedagogical integration of ICT: Ghana report.

- ↑ Marshall, Lillie. "Fun Facts about Ghana's School Systems". Around the World L. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

References

- Ministry of Education (July 2013). "Education Sector Performance Report" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Republic of Ghana. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Atuahene, Ansah (23 July 2013). "A Descriptive Assessment of Higher Education Access, Participation, Equity, and Disparity in Ghana". SageOpen. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- NUFFIC (January 2013). "Country Module: Ghana" (PDF). Netherlands Organisation for International Cooperation in Higher Education. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

External links

State-Institutions

- Ministry of Education- Responsible for initiating, formulating, coordinating and reviewing all education policies in Ghana

- List of the "Agencies" attached to the Ministry of Education - includes the Ghana Education Service (GES), the National Accreditation board (NAB), the National Council for Tertiary Education(NCTE)...

Data and reports from external institutions

- "Country Module: Ghana", NUFFIC(2013) - Overview of the Educational system by the Netherlands organization for International Cooperation in Higher Education.

- "Vocational Education" in Ghana, UNESCO-UNEVOC (2012) - Overview of the vocational Education system

- "Education in Ghana: A fact sheet", UNICEF(2012) - A 2-page analysis backed by numerous data.

- Review of Education Sector Analysis in Ghana 1987-1998, WGESA