Euclid's Elements

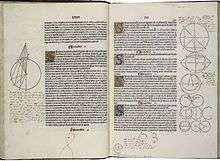

.jpg) The frontispiece of Sir Henry Billingsley's first English version of Euclid's Elements, 1570 | |

| Author | Euclid, and translators |

|---|---|

| Language | Ancient Greek, translations |

| Subject | Euclidean geometry, elementary number theory |

| Genre | Mathematics |

Publication date | circa 300 BC |

| Pages | 13 books, or more in translation with scholia |

Euclid's Elements (Ancient Greek: Στοιχεῖα Stoicheia) is a mathematical and geometric treatise consisting of 13 books attributed to the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid in Alexandria, Ptolemaic Egypt circa 300 BC. It is a collection of definitions, postulates (axioms), propositions (theorems and constructions), and mathematical proofs of the propositions. The books cover Euclidean geometry and the ancient Greek version of elementary number theory. The work also includes an algebraic system that has become known as geometric algebra, which is powerful enough to solve many algebraic problems,[1] including the problem of finding the square root of a number.[2] Elements is the second-oldest extant Greek mathematical treatise after Autolycus' On the Moving Sphere,[3] and it is the oldest extant axiomatic deductive treatment of mathematics. It has proven instrumental in the development of logic and modern science. According to Proclus, the term "element" was used to describe a theorem that is all-pervading and helps furnishing proofs of many other theorems. The word element in the Greek language is the same as letter. This suggests that theorems in the Elements should be seen as standing in the same relation to geometry as letters to language. Later commentators give a slightly different meaning to the term element, emphasizing how the propositions have progressed in small steps, and continued to build on previous propositions in a well-defined order.[4]

Euclid's Elements has been referred to as the most successful[5][6] and influential[7] textbook ever written. Being first set in type in Venice in 1482, it is one of the very earliest mathematical works to be printed after the invention of the printing press and was estimated by Carl Benjamin Boyer to be second only to the Bible in the number of editions published,[7] with the number reaching well over one thousand.[8] For centuries, when the quadrivium was included in the curriculum of all university students, knowledge of at least part of Euclid's Elements was required of all students. Not until the 20th century, by which time its content was universally taught through other school textbooks, did it cease to be considered something all educated people had read.[9]

History

Basis in earlier work

Scholars believe that the Elements is largely a collection of theorems proven by other mathematicians, supplemented by some original work.

Proclus (412 – 485 AD), a Greek mathematician who lived around seven centuries after Euclid, wrote in his commentary on the Elements: "Euclid, who put together the Elements, collecting many of Eudoxus' theorems, perfecting many of Theaetetus', and also bringing to irrefragable demonstration the things which were only somewhat loosely proved by his predecessors".

Pythagoras (circa 570–495 BCE) was probably the source for most of books I and II, Hippocrates of Chios (circa 470–410 BCE, not the better known Hippocrates of Kos) for book III, and Eudoxus of Cnidus (circa 408–355 BC) for book V, while books IV, VI, XI, and XII probably came from other Pythagorean or Athenian mathematicians.[11] The Elements may have been based on an earlier textbook by Hippocrates of Chios, who also may have originated the use of letters to refer to figures.[12]

Transmission of the text

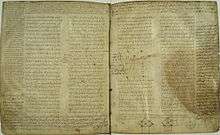

In the fourth century AD, Theon of Alexandria produced an edition of Euclid which was so widely used that it became the only surviving source until François Peyrard's 1808 discovery at the Vatican of a manuscript not derived from Theon's. This manuscript, the Heiberg manuscript, is from a Byzantine workshop around 900 and is the basis of modern editions.[13] Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 29 is a tiny fragment of an even older manuscript, but only contains the statement of one proposition.

Although known to, for instance, Cicero, no record exists of the text having been translated into Latin prior to Boethius in the fifth or sixth century.[10] The Arabs received the Elements from the Byzantines around 760; this version was translated into Arabic under Harun al Rashid circa 800.[10] The Byzantine scholar Arethas commissioned the copying of one of the extant Greek manuscripts of Euclid in the late ninth century.[14] Although known in Byzantium, the Elements was lost to Western Europe until about 1120, when the English monk Adelard of Bath translated it into Latin from an Arabic translation.[15]

The first printed edition appeared in 1482 (based on Campanus of Novara's 1260 edition),[16] and since then it has been translated into many languages and published in about a thousand different editions. Theon's Greek edition was recovered in 1533. In 1570, John Dee provided a widely respected "Mathematical Preface", along with copious notes and supplementary material, to the first English edition by Henry Billingsley.

Copies of the Greek text still exist, some of which can be found in the Vatican Library and the Bodleian Library in Oxford. The manuscripts available are of variable quality, and invariably incomplete. By careful analysis of the translations and originals, hypotheses have been made about the contents of the original text (copies of which are no longer available).

Ancient texts which refer to the Elements itself, and to other mathematical theories that were current at the time it was written, are also important in this process. Such analyses are conducted by J. L. Heiberg and Sir Thomas Little Heath in their editions of the text.

Also of importance are the scholia, or annotations to the text. These additions, which often distinguished themselves from the main text (depending on the manuscript), gradually accumulated over time as opinions varied upon what was worthy of explanation or further study.

Influence

The Elements is still considered a masterpiece in the application of logic to mathematics. In historical context, it has proven enormously influential in many areas of science. Scientists Nicolaus Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei, and Sir Isaac Newton were all influenced by the Elements, and applied their knowledge of it to their work. Mathematicians and philosophers, such as Thomas Hobbes, Baruch Spinoza, Alfred North Whitehead, and Bertrand Russell, have attempted to create their own foundational "Elements" for their respective disciplines, by adopting the axiomatized deductive structures that Euclid's work introduced.

The austere beauty of Euclidean geometry has been seen by many in western culture as a glimpse of an otherworldly system of perfection and certainty. Abraham Lincoln kept a copy of Euclid in his saddlebag, and studied it late at night by lamplight; he related that he said to himself, "You never can make a lawyer if you do not understand what demonstrate means; and I left my situation in Springfield, went home to my father's house, and stayed there till I could give any proposition in the six books of Euclid at sight".[17] Edna St. Vincent Millay wrote in her sonnet "Euclid alone has looked on Beauty bare", "O blinding hour, O holy, terrible day, When first the shaft into his vision shone Of light anatomized!". Einstein recalled a copy of the Elements and a magnetic compass as two gifts that had a great influence on him as a boy, referring to the Euclid as the "holy little geometry book".[18]

The success of the Elements is due primarily to its logical presentation of most of the mathematical knowledge available to Euclid. Much of the material is not original to him, although many of the proofs are his. However, Euclid's systematic development of his subject, from a small set of axioms to deep results, and the consistency of his approach throughout the Elements, encouraged its use as a textbook for about 2,000 years. The Elements still influences modern geometry books. Further, its logical axiomatic approach and rigorous proofs remain the cornerstone of mathematics.

Outline of Elements

Contents of the books

Books 1 through 4 deal with plane geometry:

- Book 1 contains Euclid's 10 axioms (5 named 'postulates'—including the parallel postulate—and 5 named 'common notions') and the basic propositions of geometry: the pons asinorum (proposition 5), the Pythagorean theorem (proposition 47), equality of angles and areas, parallelism, the sum of the angles in a triangle, and the three cases in which triangles are "equal" (have the same area).

- Book 2 is commonly called the "book of geometric algebra" because most of the propositions can be seen as geometric interpretations of algebraic identities, such as a(b + c + ...) = ab + ac + ... or (2a + b)2 + b2 = 2(a2 + (a + b)2). It also contains a method of finding the square root of a given number.

- Book 3 deals with circles and their properties: inscribed angles, tangents, the power of a point, Thales' theorem

- Book 4 constructs the incircle and circumcircle of a triangle, and constructs regular polygons with 4, 5, 6, and 15 sides

Books 5 through 10 introduce ratios and proportions:

- Book 5 is a treatise on proportions of magnitudes. Proposition 25 has as a special case the inequality of arithmetic and geometric means.

- Book 6 applies proportions to geometry: similar figures.

- Book 7 deals strictly with elementary number theory: divisibility, prime numbers, Euclid's algorithm for finding the greatest common divisor, least common multiple. Propositions 30 and 32 together are essentially equivalent to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic stating that every positive integer can be written as a product of primes in an essentially unique way, though Euclid would have had trouble stating it in this modern form as he did not use the product of more than 3 numbers.

- Book 8 deals with proportions in number theory and geometric sequences.

- Book 9 applies the results of the preceding two books and gives the infinitude of prime numbers (proposition 20), the sum of a geometric series (proposition 35), and the construction of even perfect numbers (proposition 36).

- Book 10 attempts to classify incommensurable (in modern language, irrational) magnitudes by using the method of exhaustion, a precursor to integration.

Books 11 through to 13 deal with spatial geometry:

- Book 11 generalizes the results of books 1–6 to space: perpendicularity, parallelism, volumes of parallelepipeds.

- Book 12 studies volumes of cones, pyramids, and cylinders in detail and shows, for example, that the volume of a cone is a third of the volume of the corresponding cylinder. It concludes by showing that the volume of a sphere is proportional to the cube of its radius (in modern language) by approximating its volume by a union of many pyramids.

- Book 13 constructs the five regular Platonic solids inscribed in a sphere, calculates the ratio of their edges to the radius of the sphere, and proves that there are no further regular solids.

Euclid's method and style of presentation

- "To draw a straight line from any point to any point."

- "To describe a circle with any center and distance."

Euclid, Elements, Book I, Postulates 1 & 3.[19]

Euclid's axiomatic approach and constructive methods were widely influential.

Many of Euclid's propositions were constructive, demonstrating the existence of some figure by detailing the steps he used to construct the object using a compass and straightedge. His constructive approach appears even in his geometry's postulates, as the first and third postulates stating the existence of a line and circle are constructive. Instead of stating that lines and circles exist per his prior definitions, he states that it is possible to 'construct' a line and circle. It also appears that, for him to use a figure in one of his proofs, he needs to construct it in an earlier proposition. For example, he proves the Pythagorean theorem by first inscribing a square on the sides of a right triangle, but only after constructing a square on a given line one proposition earlier.[20]

As was common in ancient mathematical texts, when a proposition needed proof in several different cases, Euclid often proved only one of them (often the most difficult), leaving the others to the reader. Later editors such as Theon often interpolated their own proofs of these cases.

Euclid's presentation was limited by the mathematical ideas and notations in common currency in his era, and this causes the treatment to seem awkward to the modern reader in some places. For example, there was no notion of an angle greater than two right angles,[21] the number 1 was sometimes treated separately from other positive integers, and as multiplication was treated geometrically he did not use the product of more than 3 different numbers. The geometrical treatment of number theory may have been because the alternative would have been the extremely awkward Alexandrian system of numerals.[22]

The presentation of each result is given in a stylized form, which, although not invented by Euclid, is recognized as typically classical. It has six different parts: First is the 'enunciation', which states the result in general terms (i.e., the statement of the proposition). Then comes the 'setting-out', which gives the figure and denotes particular geometrical objects by letters. Next comes the 'definition' or 'specification', which restates the enunciation in terms of the particular figure. Then the 'construction' or 'machinery' follows. Here, the original figure is extended to forward the proof. Then, the 'proof' itself follows. Finally, the 'conclusion' connects the proof to the enunciation by stating the specific conclusions drawn in the proof, in the general terms of the enunciation.[23]

No indication is given of the method of reasoning that led to the result, although the Data does provide instruction about how to approach the types of problems encountered in the first four books of the Elements.[24] Some scholars have tried to find fault in Euclid's use of figures in his proofs, accusing him of writing proofs that depended on the specific figures drawn rather than the general underlying logic, especially concerning Proposition II of Book I. However, Euclid's original proof of this proposition, is general, valid, and does not depend on the figure used as an example to illustrate one given configuration.[25]

Criticism

Euclid's list of axioms in the Elements was not exhaustive, but represented the principles that were the most important. His proofs often invoke axiomatic notions which were not originally presented in his list of axioms. Later editors have interpolated Euclid's implicit axiomatic assumptions in the list of formal axioms.[26]

For example, in the first construction of Book 1, Euclid used a premise that was neither postulated nor proved: that two circles with centers at the distance of their radius will intersect in two points.[27] Later, in the fourth construction, he used superposition (moving the triangles on top of each other) to prove that if two sides and their angles are equal, then they are congruent; during these considerations he uses some properties of superposition, but these properties are not described explicitly in the treatise. If superposition is to be considered a valid method of geometric proof, all of geometry would be full of such proofs. For example, propositions I.1 – I.3 can be proved trivially by using superposition.[28]

Mathematician and historian W. W. Rouse Ball put the criticisms in perspective, remarking that "the fact that for two thousand years [the Elements] was the usual text-book on the subject raises a strong presumption that it is not unsuitable for that purpose."[29]

Apocrypha

It was not uncommon in ancient time to attribute to celebrated authors works that were not written by them. It is by these means that the apocryphal books XIV and XV of the Elements were sometimes included in the collection.[30] The spurious Book XIV was probably written by Hypsicles on the basis of a treatise by Apollonius. The book continues Euclid's comparison of regular solids inscribed in spheres, with the chief result being that the ratio of the surfaces of the dodecahedron and icosahedron inscribed in the same sphere is the same as the ratio of their volumes, the ratio being

The spurious Book XV was probably written, at least in part, by Isidore of Miletus. This book covers topics such as counting the number of edges and solid angles in the regular solids, and finding the measure of dihedral angles of faces that meet at an edge.[30]

Editions

- 1460s, Regiomontanus (incomplete)

- 1482, Erhard Ratdolt (Venice), first printed edition[31]

- 1533, editio princeps by Simon Grynäus

- 1557, by Jean Magnien and Pierre de Montdoré, reviewed by Stephanus Gracilis (only propositions, no full proofs, includes original Greek and the Latin translation)

- 1572, Commandinus Latin edition

- 1574, Christoph Clavius

Translations

- 1505, Bartolomeo Zamberti (Latin)

- 1543, Niccolò Tartaglia (Italian)

- 1557, Jean Magnien and Pierre de Montdoré, reviewed by Stephanus Gracilis (Greek to Latin)

- 1558, Johann Scheubel (German)

- 1562, Jacob Kündig (German)

- 1562, Wilhelm Holtzmann (German)

- 1564–1566, Pierre Forcadel de Béziers (French)

- 1570, Henry Billingsley (English)

- 1572, Commandinus (Latin)

- 1575, Commandinus (Italian)

- 1576, Rodrigo de Zamorano (Spanish)

- 1594, Typographia Medicea (edition of the Arabic translation of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi)

- 1604, Jean Errard de Bar-le-Duc (French)

- 1606, Jan Pieterszoon Dou (Dutch)

- 1607, Matteo Ricci, Xu Guangqi (Chinese)

- 1613, Pietro Cataldi (Italian)

- 1615, Denis Henrion (French)

- 1617, Frans van Schooten (Dutch)

- 1637, L. Carduchi (Spanish)

- 1639, Pierre Hérigone (French)

- 1651, Heinrich Hoffmann (German)

- 1651, Thomas Rudd (English)

- 1660, Isaac Barrow (English)

- 1661, John Leeke and Geo. Serle (English)

- 1663, Domenico Magni (Italian from Latin)

- 1672, Claude François Milliet Dechales (French)

- 1680, Vitale Giordano (Italian)

- 1685, William Halifax (English)

- 1689, Jacob Knesa (Spanish)

- 1690, Vincenzo Viviani (Italian)

- 1694, Ant. Ernst Burkh v. Pirckenstein (German)

- 1695, C. J. Vooght (Dutch)

- 1697, Samuel Reyher (German)

- 1702, Hendrik Coets (Dutch)

- 1705, Charles Scarborough (English)

- 1708, John Keill (English)

- 1714, Chr. Schessler (German)

- 1714, W. Whiston (English)

- 1720s Jagannatha Samrat (Sanskrit, based on the Arabic translation of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi)[32]

- 1731, Guido Grandi (abbreviation to Italian)

- 1738, Ivan Satarov (Russian from French)

- 1744, Mårten Strömer (Swedish)

- 1749, Dechales (Italian)

- 1745, Ernest Gottlieb Ziegenbalg (Danish)

- 1752, Leonardo Ximenes (Italian)

- 1756, Robert Simson (English)

- 1763, Pubo Steenstra (Dutch)

- 1768, Angelo Brunelli (Portuguese)

- 1773, 1781, J. F. Lorenz (German)

- 1780, Baruch Schick of Shklov (Hebrew)[33]

- 1781, 1788 James Williamson (English)

- 1781, William Austin (English)

- 1789, Pr. Suvoroff nad Yos. Nikitin (Russian from Greek)

- 1795, John Playfair (English)

- 1803, H.C. Linderup (Danish)

- 1804, F. Peyrard (French)

- 1807, Józef Czech (Polish based on Greek, Latin and English editions)

- 1807, J. K. F. Hauff (German)

- 1818, Vincenzo Flauti (Italian)

- 1820, Benjamin of Lesbos (Modern Greek)

- 1826, George Phillips (English)

- 1828, Joh. Josh and Ign. Hoffmann (German)

- 1828, Dionysius Lardner (English)

- 1833, E. S. Unger (German)

- 1833, Thomas Perronet Thompson (English)

- 1836, H. Falk (Swedish)

- 1844, 1845, 1859 P. R. Bråkenhjelm (Swedish)

- 1850, F. A. A. Lundgren (Swedish)

- 1850, H. A. Witt and M. E. Areskong (Swedish)

- 1862, Isaac Todhunter (English)

- 1865, Sámuel Brassai (Hungarian)

- 1873, Masakuni Yamada (Japanese)

- 1880, Vachtchenko-Zakhartchenko (Russian)

- 1901, Max Simon (German)

- 1907, František Servít (Czech)[34]

- 1908, Thomas Little Heath (English)

- 1939, R. Catesby Taliaferro (English)

Currently in print

- Euclid's Elements – All thirteen books in one volume, Based on Heath's translation, Green Lion Press ISBN 1-888009-18-7.

- The Elements: Books I–XIII – Complete and Unabridged, (2006) Translated by Sir Thomas Heath, Barnes & Noble ISBN 0-7607-6312-7.

- The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements, translation and commentaries by Heath, Thomas L. (1956) in three volumes. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3)

Free versions

- Euclid's Elements Redux, Volume 1, contains books I–III, based on John Casey's translation, Starrhorse ISBN 978-1530942169[35]

- Euclid's Elements Redux, Volume 2, contains books IV-VIII, based on John Casey's translation, Starrhorse ISBN 978-1530943029[36]

See also

- Oliver Byrne (mathematician) who published a color version of Elements in 1847.

Notes

- ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 372

- ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 409

- ↑ Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". p. 101.

With the exception of the Sphere of Autolycus, surviving work by Euclid are the oldest Greek mathematical treatises extant; yet of what Euclid wrote more than half has been lost,

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 114

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece (2006) by Nigel Guy Wilson, page 278. Published by Routledge Taylor and Francis Group. Quote:"Euclid's Elements subsequently became the basis of all mathematical education, not only in the Roman and Byzantine periods, but right down to the mid-20th century, and it could be argued that it is the most successful textbook ever written."

- ↑ Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". p. 100.

As teachers at the school he called a band of leading scholars, among whom was the author of the most fabulously successful mathematics textbook ever written – the Elements (Stoichia) of Euclid.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - 1 2 Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". p. 119.

The Elements of Euclid not only was the earliest major Greek mathematical work to come down to us, but also the most influential textbook of all times. [...]The first printed versions of the Elements appeared at Venice in 1482, one of the very earliest of mathematical books to be set in type; it has been estimated that since then at least a thousand editions have been published. Perhaps no book other than the Bible can boast so many editions, and certainly no mathematical work has had an influence comparable with that of Euclid's Elements.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ The Historical Roots of Elementary Mathematics by Lucas Nicolaas Hendrik Bunt, Phillip S. Jones, Jack D. Bedient (1988), page 142. Dover publications. Quote:"the Elements became known to Western Europe via the Arabs and the Moors. There, the Elements became the foundation of mathematical education. More than 1000 editions of the Elements are known. In all probability, it is, next to the Bible, the most widely spread book in the civilization of the Western world."

- ↑ From the introduction by Amit Hagar to Euclid and His Modern Rivals by Lewis Carroll (2009, Barnes & Noble) pg. xxviii:

Geometry emerged as an indispensable part of the standard education of the English gentleman in the eighteenth century; by the Victorian period it was also becoming an important part of the education of artisans, children at Board Schools, colonial subjects and, to a rather lesser degree, women. ... The standard textbook for this purpose was none other than Euclid's The Elements.

- 1 2 3 Russell, Bertrand. A History of Western Philosophy. p. 212.

- ↑ W.W. Rouse Ball, A Short Account of the History of Mathematics, 4th ed., 1908, p. 54

- ↑ Ball, p. 38

- ↑ The Earliest Surviving Manuscript Closest to Euclid's Original Text (Circa 850); an image of one page

- ↑ L.D. Reynolds and Nigel G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars 2nd. ed. (Oxford, 1974) p. 57

- ↑ One older work claims Adelard disguised himself as a Muslim student to obtain a copy in Muslim Córdoba (Rouse Ball, p. 165). However, more recent biographical work has turned up no clear documentation that Adelard ever went to Muslim-ruled Spain, although he spent time in Norman-ruled Sicily and Crusader-ruled Antioch, both of which had Arabic-speaking populations. Charles Burnett, Adelard of Bath: Conversations with his Nephew (Cambridge, 1999); Charles Burnett, Adelard of Bath (University of London, 1987).

- ↑ Busard, H.L.L. (2005). "Introduction to the Text". Campanus of Novara and Euclid's Elements. I. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-08645-5.

- ↑ Henry Ketcham, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, at Project Gutenberg, https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/6811

- ↑ Dudley Herschbach, "Einstein as a Student," Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA, page 3, web: HarvardChem-Einstein-PDF: about Max Talmud visited on Thursdays for six years.

- 1 2 Hartshorne 2000, p. 18.

- ↑ Hartshorne 2000, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Ball, p. 55

- ↑ Ball, pp. 58, 127

- ↑ Heath (1963), p. 216

- ↑ Ball, p. 54

- ↑ Godfried Toussaint, "A new look at Euclid's second proposition," The Mathematical Intelligencer, Vol. 15, No. 3, 1993, pp. 12–23.

- ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 62

- ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 242

- ↑ Heath (1956) (vol. 1), p. 249

- ↑ Ball (1960) p. 55.

- 1 2 Boyer (1991). "Euclid of Alexandria". pp. 118–119.

In ancient times it was not uncommon to attribute to a celebrated author works that were not by him; thus, some versions of Euclid's Elements include a fourteenth and even a fifteenth book, both shown by later scholars to be apocryphal. The so-called Book XIV continues Euclid's comparison of the regular solids inscribed in a sphere, the chief results being that the ratio of the surfaces of the dodecahedron and icosahedron inscribed in the same sphere is the same as the ratio of their volumes, the ratio being that of the edge of the cube to the edge of the icosahedron, that is, . It is thought that this book may have been composed by Hypsicles on the basis of a treatise (now lost) by Apollonius comparing the dodecahedron and icosahedron. [...] The spurious Book XV, which is inferior, is thought to have been (at least in part) the work of Isidore of Miletus (fl. ca. A.D. 532), architect of the cathedral of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) at Constantinople. This book also deals with the regular solids, counting the number of edges and solid angles in the solids, and finding the measures of the dihedral angles of faces meeting at an edge.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Alexanderson & Greenwalt 2012, pg. 163

- ↑ K. V. Sarma (1997), Helaine Selin, ed., Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures, Springer, pp. 460–461, ISBN 978-0-7923-4066-9

- ↑ JNUL Digitized Book Repository

- ↑ available online, second edition 2007 commented by Petr Vopěnka

- ↑ "Euclid's 'Elements' Redux". Euclid's 'Elements' Redux. starrhorse. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Euclid's 'Elements' Redux". Euclid's 'Elements' Redux. starrhorse. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

References

- Alexanderson, Gerald L.; Greenwalt, William S. (2012), "About the cover: Billingsley's Euclid in English", Bulletin (New Series) of the American Mathematical Society, 49 (1): 163–167

- Artmann, Benno: Euclid – The Creation of Mathematics. New York, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 1999, ISBN 0-387-98423-2

- Ball, W.W. Rouse (1960). A Short Account of the History of Mathematics (4th ed. [Reprint. Original publication: London: Macmillan & Co., 1908] ed.). New York: Dover Publications. pp. 50–62. ISBN 0-486-20630-0.

- Hartshorne, Robin (2000). Geometry: Euclid and Beyond (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 9780387986500.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1956). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements (2nd ed. [Facsimile. Original publication: Cambridge University Press, 1925] ed.). New York: Dover Publications.

- (3 vols.): ISBN 0-486-60088-2 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-486-60089-0 (vol. 2), ISBN 0-486-60090-4 (vol. 3). Heath's authoritative translation plus extensive historical research and detailed commentary throughout the text.

- Heath, Thomas L. (1963). A Manual of Greek Mathematics. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43231-1.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Euclid's Elements |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elements of Euclid. |

- Multilingual edition of Elementa in the Bibliotheca Polyglotta

- Euclid (1997) [c. 300 BC]. David E. Joyce, ed. "Elements". Retrieved 2006-08-30. In HTML with Java-based interactive figures.

- Euclid's Elements in English and Greek (PDF), utexas.edu

- Richard Fitzpatrick a bilingual edition (typset in PDF format, with the original Greek and an English translation on facing pages; free in PDF form, available in print) ISBN 978-0-615-17984-1

- Heath's English translation (HTML, without the figures, public domain) (accessed February 4, 2010)

- Heath's English translation and commentary, with the figures (Google Books): vol. 1, vol. 2, vol. 3, vol. 3 c. 2

- Oliver Byrne's 1847 edition (also hosted at archive.org)– an unusual version by Oliver Byrne (mathematician) who used color rather than labels such as ABC (scanned page images, public domain)

- The First Six Books of the Elements by John Casey and Euclid scanned by Project Gutenberg.

- Reading Euclid – a course in how to read Euclid in the original Greek, with English translations and commentaries (HTML with figures)

- Sir Thomas More's manuscript

- Latin translation by Aethelhard of Bath

- Euclid Elements – The original Greek text Greek HTML

- Clay Mathematics Institute Historical Archive – The thirteen books of Euclid's Elements copied by Stephen the Clerk for Arethas of Patras, in Constantinople in 888 AD

- Kitāb Taḥrīr uṣūl li-Ūqlīdis Arabic translation of the thirteen books of Euclid's Elements by Nasīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī. Published by Medici Oriental Press(also, Typographia Medicea). Facsimile hosted by Islamic Heritage Project.

- Euclid's Elements Redux, an open textbook based on the Elements

- 1607 Chinese translations reprinted as part of Siku Quanshu, or "Complete Library of the Four Treasuries."