Atlantic puffin

| Atlantic puffin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult in breeding plumage, Iceland | |

| | |

| Call of the Atlantic Puffin, recorded on Skokholm Island, Pembrokeshire, Wales | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Tribe: | Fraterculini |

| Genus: | Fratercula |

| Species: | F. arctica |

| Binomial name | |

| Fratercula arctica (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| |

| Breeding range (blue), southern extent of summer range (black), and southern extent of winter range (red) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Alca arctica Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), also known as the common puffin, is a species of seabird in the auk family. It is the only puffin native to the Atlantic Ocean; two related species, the tufted puffin and the horned puffin, are found in the northeastern Pacific. The Atlantic puffin breeds in Iceland, Norway, Greenland, Newfoundland and many North Atlantic islands, and as far south as Maine in the west and the British Isles in the east. With a large population and a wide range, the species is not considered to be endangered, although there may be local declines in numbers. On land, it has the typical upright stance of an auk. At sea, it swims on the surface and feeds mainly on small fish, which it catches by diving underwater, using its wings for propulsion.

This puffin has a black crown and back, pale grey cheek patches and white underparts. Its broad, boldly marked red and black beak and orange legs contrast with its plumage. It moults while at sea in the winter and some of the bright-coloured facial characteristics are lost. The external appearance of the adult male and female are identical except that the male is usually slightly larger. The juvenile has similar plumage but its cheek patches are dark grey. The juvenile does not have brightly coloured head ornamentation, its bill is less broad and is dark-grey with a yellowish-brown tip, and its legs and feet are also dark. Puffins from northern populations are typically larger than their counterparts in southern parts of the range. It is generally considered that these populations are different subspecies.

Spending the autumn and winter in the open ocean of the cold northern seas, the Atlantic puffin returns to coastal areas at the start of the breeding season in late spring. It nests in clifftop colonies, digging a burrow in which a single white egg is laid. The chick mostly feeds on whole fish and grows rapidly. After about six weeks it is fully fledged and makes its way at night to the sea. It swims away from the shore and does not return to land for several years.

Colonies are mostly on islands where there are no terrestrial predators but adult birds and newly fledged chicks are at risk of attacks from the air by gulls and skuas. Sometimes a bird such as an Arctic skua will harass a puffin arriving with a beakful of fish, causing it to drop its catch. The striking appearance, large colourful bill, waddling gait and behaviour of this bird have given rise to nicknames such as "clown of the sea" and "sea parrot". It is the official bird symbol for the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Taxonomy and etymology

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cladogram of the Alcidae family[2] |

The Atlantic puffin is a species of seabird in the order Charadriiformes. It is in the auk family, Alcidae, which includes the guillemots, typical auks, murrelets, auklets, puffins and the razorbill.[3] The rhinoceros auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata) and the puffins are closely related, together composing the tribe Fraterculini.[4] The Atlantic puffin is the only species in the genus Fratercula to occur in the Atlantic Ocean. Two other species are known from the northeast Pacific, the tufted puffin (Fratercula cirrhata) and the horned puffin (Fratercula corniculata), the latter being the closest relative of the Atlantic puffin.[5]

The scientific name Fratercula comes from the Medieval Latin fratercula, friar, a reference to the black and white plumage which resembles monastic robes.[6] The specific name arctica refers to the northerly distribution of the bird, being derived from the Greek άρκτος ("arktos"), the bear, referring to the northerly constellation, the Great Bear.[7] The vernacular name puffin – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated species Manx shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), which in 1652 was known as the "Manks puffin".[8] It is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English pophyn or poffin) used for the cured carcasses.[9] The Atlantic puffin acquired the name at a much later stage, possibly because of its similar nesting habits,[10] and it was formally applied to Fratercula arctica by Pennant in 1768.[8] While the species is also known as the common puffin, "Atlantic Puffin" is the English name recommended by the International Ornithological Congress.[11]

There are considered to be three subspecies:[12]

- Fratercula arctica arctica

- Fratercula arctica grabae

- Fratercula arctica naumanni

The only morphological difference between the three is their size. Body length, wing length and size of beak all increase at higher latitudes. For example, a puffin from northern Iceland (subspecies naumanii) weighs about 650 grams (23 oz) and has a wing length of 186 millimetres (7.3 in) while one from the Faroes (subspecies grabae) weighs 400 grams (14 oz) and has a wing length of 158 millimetres (6.2 in). Individuals from southern Iceland (subspecies arctica) are intermediate between the other two in size.[13] Ernst Mayr has argued that the differences in size are clinal and are typical of variations found in peripheral population and that no subspecies should be recognised.[14]

Description

The Atlantic puffin is sturdily built with a thick-set neck and short wings and tail. It is 28 to 30 centimetres (11 to 12 in) in length from the tip of its stout bill to its blunt-ended tail. Its wingspan is 47 to 63 centimetres (19 to 25 in) and on land it stands about 20 cm (8 in) high. The male is generally slightly larger than the female, but they are coloured alike. The forehead, crown and nape are glossy black, as are the back, wings and tail. A broad black collar extends around the neck and throat. On each side of the head is a large, lozenge-shaped area of very pale grey. These face patches taper to a point and nearly meet at the back of the neck. The shape of the head creates a crease extending from the eye to the hindmost point of each patch giving the appearance of a grey streak. The eye looks almost triangular in shape because of a small, peaked area of horny blue-grey skin above it and a rectangular patch below. The irises are brown or very dark blue and each has red orbital ring. The underparts of the bird, the breast, belly and undertail coverts, are white. By the end of the breeding season, the black plumage may have lost its shine or even taken on a slightly brownish tinge. The legs are short and set well back on the body giving the bird its upright stance on land. Both legs and large webbed feet are bright orange, contrasting with the sharp black claws.[15]

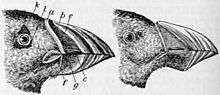

The beak is very distinctive. From the side the beak is broad and triangular but viewed from above it is narrow. The half nearest the tip is orange-red and the half nearest to the head is slate grey. There is a yellow chevron-shaped ridge separating the two parts and a yellow, fleshy strip at the base of the bill. At the joint of the two mandibles there is a yellow, wrinkled rosette. The exact proportions of the beak vary with the age of the bird. In an immature individual, the beak has reached its full length but it is not as broad as that of an adult. With time the bill deepens, the upper edge curves and a kink develops at its base. As the bird ages, one or more grooves may form on the red portion.[15] The bird has a powerful bite.[16]

The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult.[17] This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker.[18] This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it will make its way to the water and will head out to sea and not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year it will have a broader bill, paler face patches and brighter legs and beak.[15]

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically 10 metres (33 ft) above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks.[19] It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air.[20] It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony it is quiet above ground but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.[21]

Distribution

The Atlantic puffin is a bird of the colder waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. It breeds on the coasts of north west Europe, the Arctic fringes and eastern North America. The largest colony is on Iceland where 60% of the world's Atlantic puffins nest. The largest colony in the western Atlantic (estimated at more than 260,000 pairs) can be found at the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve, south of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador.[22] Other major breeding locations include the north and west coasts of Norway, the Faroe Islands, the Shetland and Orkney islands, the west coast of Greenland and the coasts of Newfoundland. Smaller sized colonies are also found elsewhere in the British Isles, the Murmansk area of Russia, Novaya Zemlya, Spitzbergen, Labrador, Nova Scotia and Maine. Islands seem particularly attractive to the birds for breeding as compared to mainland sites.[23]

While at sea, the bird ranges widely across the North Atlantic Ocean, including the North Sea, and may enter the Arctic Circle. In the summer, its southern limit stretches from northern France to Maine and in the winter the bird may range as far south as the Mediterranean Sea and North Carolina. These oceanic waters have such a vast extent of 15 to 30 million square kilometres (6 to 12 million square miles) that each bird has more than a square kilometre at its disposal and it is unsurprising that they are seldom seen out at sea.[24] In Maine, light level geolocators have been attached to the legs of puffins which store information on their whereabouts. The birds need to be re-captured in order to access the information, a difficult task. One bird was found to have covered 4,800 miles (7,700 km) of ocean in eight months, traveling northwards to the northern Labrador Sea then southeastward to the mid-Atlantic before returning to land.[16]

In a long-lived bird with a small clutch size such as the Atlantic puffin, the survival rate of adults is an important factor influencing the success of the species. Only 5% of the ringed puffins that failed to reappear at the colony did so during the breeding season. The rest were lost some time between departing from land in the summer and reappearing the following spring. The birds spend the winter widely spread out in the open ocean, though there is a tendency for individuals from different colonies to overwinter in different areas. Little is known of their behaviour and diet at sea but no correlation was found between environmental factors, such as temperature variations, and their mortality rate. A combination of the availability of food in winter and summer probably influences the survival of the birds, since individuals starting the winter in poor condition are less likely to survive than those in good condition.[25]

Behaviour

Like many seabirds, the Atlantic puffin spends most of the year far from land in the open ocean and only visits coastal areas to breed. It is a sociable bird and it usually breeds in large colonies.[26]

At sea

A running takeoff at Bear Island (Norway).

.jpg)

Atlantic puffins lead solitary existences when out at sea and this part of their life has been little studied as the task of finding even one bird on the vast ocean is formidable. When at sea, the Atlantic puffin bobs about like a cork, propelling itself through the water with powerful thrusts of its feet and keeping itself turned into the wind, even when resting and apparently asleep. It spends much time each day preening to keep its plumage in order and spread oil from the preen gland. Its downy under-plumage remains dry and provides thermal insulation. In common with other seabirds, its upper surface is black and underside white. This provides camouflage, with aerial predators unable to observe the bird against the dark watery background and underwater attackers failing to notice it as it blends in with the bright sky above the waves.[20]

When it takes off, the Atlantic puffin patters across the surface of the water while vigorously flapping its wings, before launching itself into the air.[17][20] The size of the wing is a compromise between its uses above and below water and its surface area is small relative to the bird's weight. To maintain flight, the wings need to beat very rapidly at a rate of several times each second.[27] The bird's flight is direct and low over the surface of the water and it can travel at 80 kilometres (50 mi) per hour. Landing is awkward; it either crashes into a wave crest or, in calmer water, does a belly flop. While at sea, the Atlantic puffin has its annual moult. Land birds mostly lose their primaries one pair at a time to enable them still to be able to fly, but the puffin sheds all its primaries at one time and dispenses with flight entirely for a month or two. The moult usually takes place between January and March but young birds may lose their feathers a little later in the year.[20]

Food and feeding

The Atlantic puffin diet consists almost entirely of fish, though examination of its stomach contents shows that it occasionally eats shrimps, other crustaceans, molluscs and polychaete worms, especially in more coastal waters.[28] When fishing, it swims underwater using its semi-extended wings as paddles to "fly" through the water and its feet as a rudder. It swims fast and can reach considerable depths and stay submerged for up to a minute. It can eat shallow-bodied fish as long as 18 cm (7 in) but its prey is commonly smaller fish, around 7 cm (3 in) long. It has been estimated that an adult bird needs to eat about forty of these per day—sand eels, herring, sprats and capelin being the most often consumed. It fishes by sight and can swallow small fish while submerged, but larger specimens are brought to the surface. It can catch several small fish in one dive, holding the first ones in place in its beak with its muscular, grooved tongue while it catches others. The two mandibles are hinged in such a way that they can be held parallel to hold a row of fish in place and these are also retained by inward-facing serrations on the edges of the beak. It copes with the excess salt that it swallows partly through its kidneys and partly by excretion through specialised salt glands in its nostrils.[20]

On land

In the spring, mature birds return to land, usually to the colony at which they were hatched. Birds that were removed as chicks and released elsewhere were found to show fidelity to their point of liberation.[29] They congregate for a few days on the sea in small groups offshore before returning to the cliff top nesting sites. Each large puffin colony is subdivided into sub-colonies by physical boundaries such as stands of bracken or gorse. Early arrivals take control of the best locations, the most desirable nesting sites being the densely packed burrows on grassy slopes just above the cliff edge where take-off is most easily accomplished. The birds are usually monogamous, but this is the result of their fidelity to their nesting sites rather than to their mates and they often return to the same burrows year after year. Later arrivals at the colony may find that all the best nesting sites have already been taken and be pushed towards the periphery where they are in greater danger of predation. Younger birds may come ashore a month or more after the mature birds and find no remaining nesting sites. They will not breed till the following year although it has been found that if the ground cover surrounding the colony is cut back before these sub-adults arrive, the number of successfully nesting pairs may be increased.[30]

Atlantic puffins are cautious when approaching the colony and no bird likes to land in a location where other puffins are not already present. They make several circuits of the colony before alighting. On the ground they spend much time preening, spreading oil from their preen gland and setting each feather in its correct position with beak or claw. They also spend time standing by their burrow entrances and interacting with passing birds. Dominance is shown by an upright stance, with fluffed chest feathers and cocked tail, an exaggerated slow walk, head jerking and gaping. Submissive birds lower their head and hold their body horizontal and scurry past dominant individuals. Birds normally signal their intention to take off by briefly lowering their body before running down the slope to gain momentum. If a bird is startled and takes off unexpectedly, a panic can spread through the colony with all the birds launching themselves into the air and wheeling around in a great circle. The colony is at its most active in the evening, with birds standing outside their burrows, resting on the turf or strolling around. Then the slopes empty for the night as the birds fly out to sea to roost, often choosing to do so at fishing grounds ready for early morning provisioning.[30]

The puffins are energetic burrow-engineers and repairers and the grassy slopes may be undermined by a network of tunnels. This causes the turf to dry out in summer, vegetation to die and dry soil be whirled away by the wind. Burrows sometimes collapse, and humans may cause this to happen by walking incautiously across nesting slopes. A colony on Grassholm was lost through erosion when there was so little soil left that burrows could not be made.[31] New colonies are very unlikely to start up spontaneously because this gregarious bird will only nest where others are already present. Nevertheless, the Audubon Society had success on Eastern Egg Rock Island in Maine, where, after a gap of ninety years, puffins were reintroduced and started breeding again. By 2011 there were over 120 pairs nesting on the small islet.[32] On the Isle of May on the other side of the Atlantic, only five pairs of puffins were breeding in 1958 while twenty years later there were 10,000 pairs.[33]

Reproduction

Having spent the winter alone on the ocean, it is unclear whether the Atlantic puffin meets its previous partner offshore or whether they encounter each other when they return to their nest of the previous year. On land, they soon set about improving and clearing out the burrow. Often, one stands outside the entrance while the other excavates, kicking out quantities of soil and grit that showers the partner standing outside. Some birds collect stems and fragments of dry grasses as nesting materials but others do not bother. Sometimes a beakful of materials is taken underground, only to be brought out again and discarded. Apart from nest-building, the other way in which the birds restore their bond is by billing. This is a practice in which the pair approach each other, each wagging its head from side to side, and then rattle their beaks together. This seems to be an important element of their courtship behaviour because it happens repeatedly, and the birds continue to bill, to a lesser extent, throughout the breeding season.[34]

The Atlantic puffin is sexually mature at the age of four to five years. The birds are colonial nesters, excavating burrows on grassy clifftops or reusing existing holes, and may also nest in crevices and amongst rocks and scree on occasion. It is in competition with other birds and animals for burrows. It can excavate its own hole or move into a pre-existing system dug by a rabbit and has been known to peck and drive off the original occupant. Manx shearwaters also nest underground and often live in their own burrows alongside puffins, and their burrowing activities may break through into the puffin's living quarters resulting in the loss of the egg.[35] They are monogamous (they mate for life) and give biparental care to their young. The male spends more time guarding and maintaining the nest while the female is more involved in incubation and feeding the chick.[36]

Egg-laying starts in April in more southerly colonies but seldom occurs before June in Greenland. The female lays a single white egg each year but if this is lost early in the breeding season, another might be produced.[37] Synchronous laying of eggs is found in Atlantic puffins in adjacent burrows.[38] The egg is large compared to the size of the bird, averaging 61 millimetres (2.4 in) long by 42 millimetres (1.7 in) wide and weighing about 62 grams (2.2 oz). The white shell is usually devoid of markings but soon becomes soiled with mud. The incubation responsibilities are shared by both parents. They each have two feather-free brood patches on their undersides where an enhanced blood supply provides heat for the egg. The parent on incubation duty in the dark nest chamber spends much of its time asleep with its head tucked under its wing, occasionally emerging from the tunnel to flap dust out of its feathers or take a short flight down to the sea.[37]

Total incubation time is around 39–45 days. From above ground level, the first evidence that hatching has taken place is the arrival of an adult with a beak-load of fish. For the first few days the chick may be fed with these beak-to-beak but later the fish are simply dropped on the floor of the nest beside the chick which swallows them whole. The chick is covered in fluffy black down and its eyes are open and it can stand as soon as it is hatched. Initially weighing about 42 grams (1.5 oz), it grows at the rate of 10 grams (0.35 oz) per day. Initially, one or other parents brood it, but as its appetite increases it is left alone for longer periods. Observations of a nest chamber have been made from an underground hide with peephole. It was found that the chick sleeps much of the time between its parents' visits and also involves itself in bouts of exercise. It rearranges its nesting material, picks up and drops small stones, flaps its immature wings, pulls at protruding root ends and pushes and strains against the unyielding wall of the burrow. It makes its way towards the entrance or along a side tunnel to defecate. The growing chick seems to anticipate the arrival of an adult, advancing along the burrow just before it arrives but not emerging into the open air. It retreats to the nest chamber as the adult bird brings in its load of fish.[39]

Hunting areas are often located 100 km (60 mi) or more, offshore from the nest sites, although when feeding their young, the birds venture out only half that distance.[40] It has been found that adults bringing fish to their chicks tend to arrive in groups. This is thought to benefit the bird by reducing kleptoparasitism by the Arctic skua which harasses puffins until they drop their fish loads. Predation by the great skua (Catharacta skua) is also reduced by several birds arriving simultaneously.[41]

In the Shetland Islands, sand eels (Ammodytes marinus) normally form at least 90% of the food fed to chicks. It was found that, in years where the availability of sand eels was low, breeding success rates fell, with many chicks starving to death.[42] In Norway it is the herring (Clupea harengus) that is the mainstay of the diet. When herring numbers dwindled, so did puffin numbers.[43] In Labrador the puffins seemed more flexible and when the staple forage fish capelin (Mallotus villosus) declined in availability, they were able to adapt and feed the chicks on other prey species.[44]

The chicks take from 34 to 50 days to fledge, the period depending on the abundance of their food supply. In years of fish shortage, the whole colony may experience a longer fledgling period but the normal range is 38 to 44 days, by which time chicks will have reached about 75% of their mature body weight. The chick may come to the burrow entrance to defecate but does not usually emerge into the open[45] and seems to have an aversion to light until it is nearly fully fledged.[46] Although the supply of fish by the adults reduces over the last few days spent in the nest, the chick is not abandoned as happens in the Manx shearwater. On occasions, an adult has been observed provisioning a nest even after the chick has departed. During the last few days underground, the chick sheds its down and the juvenile plumage is revealed. Its relatively small beak and its legs and feet are a dark colour and it lacks the white facial patches of the adult. The chick finally leaves its nest at night, when the risk of predation is at its lowest. When the moment arrives, it emerges from the burrow, usually for the first time, and walks, runs and flaps its way to the sea. It cannot fly properly yet so descending a cliff is perilous; when it reaches the water it paddles out to sea, and may be three kilometres (two miles) away from the shore by daybreak. It does not congregate with others of its kind and will not return to land for two or three years.[45]

Predators and parasites

Atlantic puffins are probably safest when out at sea. Here, the dangers are often from below the water rather than above, and puffins can sometimes be seen putting their heads underwater to peer around for predators. Seals have been known to kill puffins and large fish may also do so. Most puffin colonies are on small islands, and this is no coincidence as it avoids predation by ground-based mammals such as foxes, rats, stoats and weasels, cats and dogs. When they come ashore, the birds are still at risk and the main threats come from the sky.[47]

Aerial predators of the Atlantic puffin include the great black-backed gull (Larus marinus), the great skua (Stercorarius skua), and similar-sized species, which can catch a bird in flight, or attack one that is unable to escape fast enough on the ground. On detecting danger, puffins take off and fly down to the safety of the sea or retreat into their burrows, but if caught they defend themselves vigorously with beak and sharp claws. When the puffins are wheeling round beside the cliffs it becomes very difficult for a predator to concentrate on a single bird while any individual isolated on the ground is at greater risk.[48] Smaller gull species like the herring gull (L. argentatus) and the lesser black-backed gull are hardly able to bring down a healthy adult puffin. They stride through the colony taking any eggs that have rolled towards burrow entrances or recently hatched chicks that have ventured too far towards the daylight. They will also steal fish from puffins returning to feed their young.[49] Where it nests on the tundra in the far north, the Arctic skua (Stercorarius parasiticus) is a terrestrial predator, but at lower latitudes it is a specialised kleptoparasite, concentrating on auks and other seabirds. It harasses puffins while they are airborne forcing them to drop their catch which it then snatches up.[50]

Both the guillemot tick Ixodes uriae and the flea Ornithopsylla laetitiae (probably originally a rabbit flea) have been recorded from the nests of puffins. Other fleas which have been found on the birds include Ceratophyllus borealis, Ceratophyllus gallinae, Ceratophyllus garei, Ceratophyllus vagabunda and the common rabbit flea Spilopsyllus cuniculi.[51]

Relationship with humans

Status and conservation

In its Red List of Threatened Species, the International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Atlantic puffin as vulnerable. It has a very large total population and an extensive range which covers over 1,620,000 square kilometres (630,000 sq mi). Although the number of birds seems to be decreasing, the decline does not reach the threshold for "vulnerable" status.[1] Some of the causes of population decline may be increased predation by gulls and skuas, the introduction of rats, cats, dogs and foxes onto some islands used for nesting, contamination by toxic residues, drowning in fishing nets, declining food supplies and climate change.[52] On the island of Lundy the number of puffins decreased from 3,500 pairs in 1939 to 10 pairs in 2000. This was mainly due to the rats that had proliferated on the island and were eating eggs and young chicks. Following the elimination of the rats, it is hoped that populations will recover,[53] and in 2005, a juvenile was seen, believed to be the first chick raised on the island for thirty years.[54]

On the other hand, puffin numbers increased considerably in the late twentieth century in the North Sea, including on the Isle of May and the Farne Islands where numbers have been increasing by about 10% per year. In the 2013 breeding season, nearly 40,000 pairs were recorded on the Farne Islands, a slight increase on the 2008 census and on the previous year's poor season when some of the burrows flooded.[55] This number is dwarfed by the Icelandic colonies with five million pairs breeding, the Atlantic puffin being the most populous bird on the island.[56] In the Westman Islands, where about half Iceland's puffins breed, the birds were almost driven to extinction by overharvesting around 1900 and a thirty-year ban on hunting was put in place. When stocks recovered, a different method of harvesting was used and now hunting is maintained at a sustainable level.[57] Nevertheless, a further hunting ban covering the whole of Iceland was called for in 2011, although the puffin's lack of recent breeding success was being blamed on a diminution in food supply rather than overharvesting.[58]

SOS Puffin is a conservation project at the Scottish Seabird Centre at North Berwick to save the puffins on islands in the Firth of Forth. Puffin numbers on the island of Craigleith, once one of the largest colonies in Scotland with 28,000 pairs, have declined dramatically to just a few thousand due to the invasion of a large introduced plant, the tree mallow (Lavatera arborea). This has spread across the island in dense thickets and prevents the puffins from finding suitable sites for burrowing and breeding. The project has the support of over 700 volunteers and progress has been made in cutting back the plants, with puffins returning in greater numbers to breed.[59] Another conservation measure undertaken by the Centre is to encourage motorists to check under their cars in late summer before driving off as young puffins, disorientated by the street lights, may land in the town and take shelter underneath the vehicles.[60]

Project Puffin is an effort initiated in 1973 by Dr. Stephen W. Kress of the National Audubon Society to restore Atlantic puffins to nesting islands in the Gulf of Maine. Eastern Egg Rock Island in Muscongus Bay, about 6 miles (9.7 km) away from Pemaquid Point, had been occupied by nesting puffins until 1885, when the birds disappeared because of overhunting. Counting on the fact young puffins usually return to breed on the same island where they fledged, a team of biologists and volunteers translocated 10–14 days old nestlings from Great Island in Newfoundland to Eastern Egg Rock. The young were placed into artificial sod burrows, and fed with vitamin-fortified fish daily for about one month. Such yearly translocations took place until 1986, with 954 young puffins being moved in total. Each year before fledging, the young were individually tagged. The first adults returned to the island by 1977. Puffin decoys had been installed on the island to fool the puffins into thinking they were part of an established colony. This did not catch on at first, but in 1981 four pairs nested on the island. In 2014, 148 nesting pairs were counted on the island. In addition to demonstrating the feasibility of re-establishing a seabird colony, the project showed the usefulness of using decoys, and eventually call recordings and mirrors, to facilitate such reestablishment.[61]

Pollution

Since the Atlantic puffin spends its winters on the open ocean, it is susceptible to human actions and catastrophes such as oil spills. Oiled plumage has a reduced ability to insulate and makes the bird more vulnerable to temperature fluctuations and less buoyant in the water.[62] Many birds die, and others, while attempting to remove the oil by preening, ingest and inhale toxins. This leads to inflammation of the airways and gut and in the longer term, damage to liver and kidneys. This trauma can contribute to a loss of reproductive success and harm to developing embryos.[38] An oil spill occurring in winter, when the puffins are far out at sea, may affect them less than inshore birds as the crude oil slicks soon get broken up and dispersed by the churning of the waves. When oiled birds get washed up on beaches around Atlantic coasts, only about 1.5% of the dead auks are puffins, but many others may have died far from land and sunk.[63] After the oil tanker Torrey Canyon shipwreck and oil spill in 1967, few dead puffins were recovered, but the number of puffins breeding in France the following year was reduced to 16% of its previous level.[64]

The Atlantic puffin and other pelagic birds are excellent bioindicators of the environment as they occupy a high trophic level. Heavy metals and other pollutants are concentrated through the food chain and, as fish are the primary food source for Atlantic puffins, there is great potential for them to bioaccumulate heavy metals such as mercury and arsenic. Measurements can be made on eggs, feathers or internal organs and beached bird surveys, accompanied by chemical analysis of feathers, can be effective indicators of marine pollution by lipophilic substances as well as metals. In fact these surveys can be used to provide evidence of the adverse effects of a particular pollutant, using fingerprinting techniques to provide evidence suitable for the prosecution of offenders.[65][66]

Climate change

Climate change may well affect populations of seabirds in the northern Atlantic. The most important demographic may be an increase in the sea surface temperature which may have benefits for some northerly Atlantic puffin colonies.[67] Breeding success depends on there being ample supplies of food at the time of maximum demand, as the chick grows. In northern Norway the main food item fed to the chick is the young herring. The success of the newly hatched fish larvae during the previous year was governed by the water temperature, which controlled plankton abundance and this in turn influenced the growth and survival of the first-year herring. The breeding success of Atlantic puffin colonies has been found to correlate in this way with the water surface temperatures of the previous year.[68]

In Maine, on the other side of the Atlantic, shifting fish populations due to changes in sea temperature are being blamed for the lack of availability of the herring which is the staple diet of the puffins in the area. Some adult birds have become emaciated and died. Others have been provisioning the nest with butterfish (Peprilus triacanthus) but these are often too large and deep-bodied for the chick to swallow, causing it to die from starvation. Maine is on the southerly edge of the bird's breeding range and with changing weather patterns, this may be set to contract northwards.[69]

Tourism

.jpg)

Breeding colonies of Atlantic puffins provide an interesting spectacle for both bird watchers and tourists. For example, four thousand puffins nest each year on islands off the coast of Maine and visitors can view them from tour boats which operate during the summer months. There is a Project Puffin Visitor Centre in Rockland providing information on the birds and their lives, and on the other conservation projects being undertaken by the National Audubon Society who run the centre.[70] Similar tours operate in Iceland,[71] the Hebrides,[72] and Newfoundland.[73]

Hunting

Puffins have been hunted by man since time immemorial. Coastal communities and island dwellers with few natural resources at their disposal, made good use of the seafoods that they found on their cliffs and shores. Puffins were caught and eaten fresh, salted in brine or smoked and dried. Their feathers were used in bedding and their eggs were eaten, but not to the same extent as those of some other seabirds, being more difficult to extract from the nest. In most countries, Atlantic puffins are now protected by legislation, and in the countries where hunting is still permitted, strict laws prevent over-exploitation. They are still caught and eaten in Iceland and the Faroe Islands,[74] but there have been calls for an outright ban on hunting them in Iceland because of concern over the dwindling number of birds successfully raising chicks.[75]

Traditional means of capture varied across the birds' range and nets and rods were used in various ingenious ways. A typical device used in the Faroes was a "fleyg". This was a long pole with a net on the end laid flat on the ground. A few dead puffins were strewn around to entice incoming birds to land, and the net was flicked upwards to scoop a bird from the air as it slowed before alighting. Most of the birds caught were sub-adults, and a skilled hunter could gather two or three hundred in a day. Another method of capture, used in St Kilda, involved the use of a flexible pole with a noose on the end. This was pushed along the ground towards the intended target, which advanced to inspect the noose as its curiosity overcame its caution. A flick of the wrist would flip the noose over the victim's head and it was promptly killed, before its struggles could alarm other birds nearby.[76]

In culture

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.[77] In August 2007, the Atlantic puffin was proposed as the official symbol of the Liberal Party of Canada by its deputy leader Michael Ignatieff, after he observed a colony of these birds and became fascinated by their behaviour.[78] The Norwegian municipality of Værøy has an Atlantic puffin as its civic emblem.[79] Puffins are viewed with affection because they are colourful and full of character. They have been given a number of endearing names including "clowns of the sea" and "sea parrots", and juvenile puffins may be called "pufflings".[80]

A number of islands have been named after the bird. The island of Lundy in the United Kingdom is reputed to derive its name from the Norse lund-ey or "puffin island".[81] An alternative explanation has been suggested connected with another meaning of the word lund referring to a copse or wooded area. The Vikings might have found the island a useful refuge and restocking point after their depredations on the mainland .[82] The island issued its own coins and, in 1929, its own stamps with denominations in "puffins".[83] Other countries and dependencies which have depicted Atlantic puffins on their stamps include Alderney, Canada, the Faroe Islands, France, Gibraltar, Guernsey, Iceland, Ireland, the Isle of Man, Jersey, Norway, Portugal, Russia, Slovenia, St Pierre et Miquelon and the United Kingdom.[84] The LPO, a French biodiversity charity focussing on the protection of birds, uses a pair of Atlantic puffins as its emblem.[85]

The publisher of paperbacks, Penguin Books, introduced a range of books for children under the Puffin Books brand in 1939. At first these were non-fiction titles but these were soon followed by a fiction list of well-known authors. The demand was so great that Puffin Book Clubs were introduced in schools to encourage reading, and a children's magazine Puffin Post was established.[86] There is a tradition on the Icelandic island of Heimaey for the children to rescue young puffins, a fact recorded in Bruce McMillan's photo-illustrated children's book Nights of the Pufflings (1995). The fledglings emerge from the nest and try to make their way to the sea but sometimes get confused, perhaps by the street lighting, ending up by landing in the village. The children collect them and liberate them to the safety of the sea.[57]

References

- 1 2 BirdLife International. (2015). Fratercula arctica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015.

- ↑ Smith, N.A. (2011). "Taxonomic revision and phylogenetic analysis of the flightless Mancallinae (Aves, Pan-Alcidae)". ZooKeys. 91 (91): 1–116. doi:10.3897/zookeys.91.709. PMC 3084493

. PMID 21594108.

. PMID 21594108. - ↑ Lepage, Denis. "Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica) (Linnaeus, 1758)". Avibase. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Guthrie, Daniel A.; Howell, Thomas, W.; Kennedy, George L. (1999). "A new species of extinct late Pleistocene puffin (Aves: Alcidae) from the southern California Channel Islands" (PDF). Proceedings of the 5th California Islands Symposium: 525–530.

- ↑ Harrison, Peter (1988). Seabirds. Helm. pp. 404–405. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "Bear: Ursus arctos". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- 1 2 Lockwood, W. B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

- ↑ "Puffin". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Lee & Haney (1996)

- ↑ Gill, Frank, and Minturn Wright, Birds of the World: Recommended English Names Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. 2006.

- ↑ Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2013). "Fratercula arctica: Atlantic Puffin". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Petersen, Aevar (1976). "Size variables in puffins Fratercula arctica from Iceland, and bill features as criteria of age". Ornis Scandinavica. 7 (2): 185–192. doi:10.2307/3676188. JSTOR 3676188.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1969). "Discussion: Footnotes on the philosophy of biology". Philosophy of Science. 36 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1086/288246. JSTOR 186171.

- 1 2 3 Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 19–23

- 1 2 "Cabot discovery". Audubon: Project Puffin. National Audubon Society. 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- 1 2 "Fratercula arctica". Boreal Forests of the World. Faculty of Natural Resources Management, Lakehead University. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ "Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica)". Planet of Birds. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ↑ Sibley, David (2000). The North American Bird Guide. Pica Press. pp. 252–253. ISBN 978-1-873403-98-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 30–43

- ↑ "Atlantic Puffin: Sound". All about birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- ↑ "Witless Bay Ecological Reserve" (PDF). A guide to our wilderness and ecological reserves. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador: Parks & Natural Areas Division. 2006. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 24–29

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 30

- ↑ Harris, M. P.; Anker-Nilssen, T.; McCleery, R. H. (2005). "Effect of wintering area and climate on the survival of adult Atlantic puffins Fratercula arctica in the eastern Atlantic" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 297: 283–296. doi:10.3354/meps297283.

- ↑ Crick, Humphrey Q P (1993). "Puffin". In Gibbons, David Wingham; Reid, James B; Chapman, Robert A. The New Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland: 1988–1991. London: T. & A. D. Poyser. p. 230. ISBN 0-85661-075-5.

- ↑ Kovacs, Christopher E.; Meyers, Ron A. (2000). "Anatomy and histochemistry of flight muscles in a wing-propelled diving bird, the Atlantic puffin, Fratercula arctica" (PDF). Journal of Morphology. 244 (2): 109–125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(200005)244:2<109::AID-JMOR2>3.0.CO;2-0. PMID 10761049.

- ↑ Falk, Knud; Jensen, Jens-Kjeld; Kampp, Kaj (1992). "Winter diet of Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica) in the Northeast Atlantic". Colonial Waterbirds. 15 (2): 230–235. doi:10.2307/1521457. JSTOR 1521457.

- ↑ Kress, Stephen W.; Nettleship, David N. (1988). "Re-establishment of Atlantic Puffins (Fratercula arctica) at a former breeding site in the Gulf of Maine". Journal of Field Ornithology. 59 (2): 161–170. JSTOR 4513318.

- 1 2 Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 44–65

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 48

- ↑ "Eastern Egg Rock". Project Puffin. Audubon. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 47

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 72

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 107

- ↑ Creelman, E.; Storey, A. E. (1991). "Sex differences in reproductive behavior of Atlantic Puffins". The Condor. 93 (2): 390–398. doi:10.2307/1368955. JSTOR 1368955.

- 1 2 Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 78–81

- 1 2 Ehrlich et al. (1988)

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 82–95

- ↑ Lilliendahl, K.; Solmundsson, J.; Gudmundsson, G. A.; Taylor, L. (2003). "Can surveillance radar be used to monitor the foraging distribution of colonially breeding alcids?". Condor. 105 (1): 145–150. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2003)105[145:CSRBUT]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Merkel, Flemming Ravn; Nielsen, Niels Kurt; Olsen, Bergur (1998). "Clumped arrivals at an Atlantic Puffin colony". Colonial Waterbirds. 21 (2): 261–267. doi:10.2307/1521918. JSTOR 1521918.

- ↑ Martin, A. R. (1989). "The diet of Atlantic Puffin Fratercula arctica and Northern Gannet Sula bassana chicks at a Shetland colony during a period of changing prey availability". Bird Study. 36 (3): 170–180. doi:10.1080/00063658909477022.

- ↑ Barrett, R. T.; Anker-Nilssen, T.; Rikardsen, F.; Valde, K.; Røv, N.; Vader, W. (1987). "The food, growth and fledging success of Norwegian puffin chicks Fratercula arctica in 1980–1983". Ornis Scandinavica. 18 (2): 70–83. doi:10.2307/3676842. JSTOR 3676842.

- ↑ Baillie, Shauna M.; Jones, Ian L (2003). "Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica) chick diet and reproductive performance at colonies with high and low capelin (Mallotus villosus) abundance". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 81 (9): 1598–1607. doi:10.1139/z03-145.

- 1 2 Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 85–99

- ↑ Couzens, Dominic (2013). The Secret Lives of Puffins. A. C. Black. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-4081-8667-1.

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 102–103

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) p. 51

- ↑ Rodway, Michael S.; Chardine, John W.; Montevecchi, William A. (1998). "Intra-colony variation in breeding performance of Atlantic Puffins". Colonial Waterbirds. 21 (2): 171–184. doi:10.2307/1521904. JSTOR 1521904.

- ↑ Jones, Trevor (2002). "Plumage polymorphism and kleptoparasitism in the Arctic skua Stercorarius parasiticus" (PDF). Atlantic Seabirds. 4 (2): 41–52.

- ↑ Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1957). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. MacMillan. pp. 116, 231. ASIN B0000CKZP6.

- ↑ Mitchell, P. I.; Newton, S. F.; Ratcliffe, N.; Dunn, T. E. (1 August 2011). "Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland: Results of the Seabird 2000 Census (1998–2002)" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "Lundy puffins back from the brink". BBC Devon. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "First Puffin chick spotted on Lundy". Press release. English Nature. 14 July 2005. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "Puffin census on Farne Islands shows numbers rising". BBC News: Science and Environment. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ↑ Kristjánsson, Jóhann K. (22 July 2012). "Lundi (Fratercula artica)" (in Icelandic). Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Puffins in Iceland". Iceland Nature. Iceland on the Web. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ "Outright puffin hunting ban suggested in face of population crisis". IceNews. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "SOS Puffin". Scottish Seabird Centre. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ "North Berwick drivers warned over hidden puffins". BBC News: Scotland. 30 July 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "History of Project Puffin". Project Puffin. Audubon. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ Dunnet, G.; Crisp, D.; Conan, G.; Bourne, W. (1982). "Oil pollution and seabird populations". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B. 297 (1087): 413–427. doi:10.1098/rstb.1982.0051.

- ↑ Mead, C. J. (1974). "The results of ringing auks in Britain and Ireland". Bird Study. 21 (1): 45–86. doi:10.1080/00063657409476401.

- ↑ Goethe, Friedrich (1968). "The effects of oil pollution on populations of marine and coastal birds". Helgoländer wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen. 17 (1–4): 370–374. doi:10.1007/BF01611237.

- ↑ Perez-Lopez, M.; Cid, F.; Oropesa, A.; Fidalgo, L.; Beceiro, A.; Soler, F. (2006). "Heavy metal and arsenic content in seabirds affected by the Prestige oil spill on the Galician coast (NW Spain)". Science of the Total Environment. 359 (1–3): 209–220. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2005.04.006. PMID 16696110.

- ↑ Furness, R. W.; Camphuysen, C. J. (1997). "Seabirds as monitors of the marine environment". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 54 (4): 726–737. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1997.0243.

- ↑ Sandvik, Hanno; Coulson, Tim; Saether, Bernt-Erik (2008). "A latitudinal gradient in climate effects on seabird demography: results from interspecific analyses". Global Change Biology. 14 (4): 793–713. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01533.x.

- ↑ Durant, J.M.; Anker-Nilssen, T; Stenseth, N.C. (2003). "Trophic interactions under climate fluctuations: the Atlantic puffin as an example". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 270 (1523): 1461–1466. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2397. PMC 1691406

. PMID 12965010.

. PMID 12965010. - ↑ "Atlantic puffin population in peril as fish stocks shift, ocean waters heat up". The Record.com. Associated Press. 2 June 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ↑ "Bird watching: Puffins". Maine. Maine Office of Tourism. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Oswell, Paul (11 April 2011). "Iceland holidays: Volcano walks and puffin spotting (or not) in the Westman Islands". MailOnline. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ "Wild Scotland – The Western Isles"

- ↑ Birdwatching, Newfoundland and Labrador Tourism

- ↑ Lowther, Peter E.; Diamond, A. W.; Kress, Stephen W.; Robertson, Gregory J.; Russell, Keith (2002). "Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica)". The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 13 June 2013. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Outright puffin hunting ban suggested in face of population crisis". IceNews. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ↑ Boag & Alexander (1995) pp. 112–113

- ↑ Higgins, Jenny (2011). "The Arms, Seals, and Emblems of Newfoundland and Labrador". Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Canadian Press (30 August 2007). "Excrement-hiding bird championed as Liberal symbol". CTV News. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ "Værøy". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "Nature: Atlantic Puffin". Wildlife. BBC. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Swann, H. Kirke (1913). A dictionary of English and Folk-names of British Birds. London: Witherby and Co. p. 149.

- ↑ "Meaning of lund-ey". Pete Robson's Lundy Island Site. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ "Lundy Island Cinderella". King George V Silver Jubilee. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ Gibbins, Chris. "Atlantic Puffin Stamps". Birds of the World on Postage Stamps. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- ↑ "LPO". Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ "The story of Puffin". Puffin Books. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Boag, David; Alexander, Mike (1995). The Puffin. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2596-6.

- Ehrlich, P.R.; Dobkin, D.S.; Wheye, D. (1988). The Birder's Handbook: A Field Guide to The Natural History of North American Birds (Atlantic Puffin ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 207, 209–214. ISBN 0-671-62133-5.

- Lee, D. S. & Haney, J. C. (1996) "Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus)", in: The Birds of North America, No. 257, (Poole, A. & Gill, F. eds). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences, and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC

External links

-

Media related to Fratercula arctica at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fratercula arctica at Wikimedia Commons -

Data related to Fratercula arctica at Wikispecies

Data related to Fratercula arctica at Wikispecies

.jpg)