Gallimimus

| Gallimimus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, 70 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton cast, Natural History Museum, London | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Ornithomimosauria |

| Family: | †Ornithomimidae |

| Subfamily: | †Ornithomiminae |

| Genus: | †Gallimimus Osmólska, Roniewicz & Barsbold, 1972 |

| Species: | †G. bullatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gallimimus bullatus Osmólska, Roniewicz & Barsbold, 1972 | |

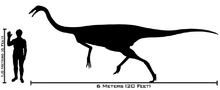

Gallimimus (/ˌɡælᵻˈmaɪməs/ GAL-i-MY-məs; meaning "chicken mimic") is a genus of ornithomimid theropod dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous period (Maastrichtian stage) Nemegt Formation of Mongolia. With individuals as long as 8 m (26 ft),[1] it was one of the largest ornithomimosaurs.[2] Gallimimus is known from multiple individuals, ranging from juvenile (about 0.5 m tall at the hip) to adult (about 2 m tall at the hip). The type species is G.bullatus, which means "capsuled chicken mimic".[3]

Description

Gallimimus was rather ostrich-like, with a small head, toothless beak, large eyes, a long neck, short arms, long legs, and a long tail. A diagnostic character of Gallimimus is a distinctly short 'hand' relative to the humerus length, when compared to other ornithomimids. The tail was used as a counterbalance. The eyes were located on the sides of its head, meaning that it did not possess binocular vision. Like most modern birds and other theropods, it had hollow bones. Gallimimus had a number of adaptations which suggest good running ability, such as a strong ilium, heavy tail base, long limbs, a long tibia and metatarsus, and short toes, but it is unknown how fast it could run. All ornithomimids had long skulls, but that of Gallimimus was exceptionally elongated, due to an elongation of the snout. The snouts of the juvenile specimens are much shorter.

Norwegian researcher Jørn H. Hurum in 2001 published a detailed description of a complete lower jaw bone from Gallimimus bullatus.[4] He observed that the bones composing the jaw were "paper thin", and corrects minor mistakes made in previous reconstructions of the lower jaw of G. bullatus.[5] He also observed that the tight intramandibular joint would prevent any movement between the front and rear portions of the lower jaw.[4]

Discovery

The first fossil remains of this dinosaur were discovered in early August 1963 by a team of Professor Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska at Tsagan Khushu during a Polish-Mongolian expedition to the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. The find was reported by her in 1965.[6] In 1972, it was named and described by paleontologists Rinchen Barsbold, Halszka Osmólska, and Ewa Roniewicz. The only named species is the type species Gallimimus bullatus. The generic name is derived from Latin gallus, "chicken", and mimus, "mimic", in reference to the neural arches of the front neck vertebrae which resemble those of the Galliformes. The specific name is derived from Latin bulla, a magic capsule worn by Roman youth around the neck, in reference to a bulbous swelling in the braincase on the underside of the parasphenoid, in the form of a capsule.[3] The holotype specimen, IGM 100/11, consists of a partial skeleton including the skull and lower jaws. It is a larger skeleton; several other partial skeletons have been described, most of them of juveniles, and numerous single bones.

A second species announced by Barsbold in 1996, "Gallimimus mongoliensis" based on specimen IGM 100/14 from the older Bayanshiree Formation, has never been formally referred to this genus. In a reanalysis of the nearly complete skeleton of "Gallimimus mongoliensis" Barsbold concluded in 2006 that it is not a species of Gallimimus but may represent a new, currently unnamed ornithomimid genus.[7]

Phylogeny

Gallimimus was assigned to the Ornithomimidae in 1972. This is confirmed by recent cladistic analyses.

The following cladogram is based on Xu et al., 2011:[8]

| Ornithomimidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Beak and paleoecology

The feeding habits of ornithomimids have been controversial. The original describers thought Gallimimus preyed upon small animals, using its long arms as rakes to remove covering plant material on the soil. Later suggestions included omnivory and herbivory.

In 2001, Norell et al. reported a specimen of Gallimimus (IGM 100/1133), a skull with soft tissue preservation. This specimen, as well as another new fossil skull of Ornithomimus, had a keratinous beak with vertical grooves projecting from the bony upper mandible. These structures are reminiscent of the lamellae seen in ducks, in which they function to strain small edible items like plants, forams, mollusks, and ostracods from the water. The authors further noted that ornithomimids were abundant in mesic environments, and rarer in more arid environments, suggesting that they may have depended on waterborne sources of food, possibly filter feeding. They noted that primitive ornithomimids had well-developed teeth, while derived forms were edentulous and probably could not feed on large animals.[9]

One later paper questioned the conclusions of Norell et al. Barrett (2005) noted that vertical ridges are seen on the inner surface of the beaks of strictly herbivorous turtles, and also the hadrosaurid Edmontosaurus. Barrett also offered calculations, estimating how much energy could be derived from filter feeding and the probable energy needs of an animal as big as Gallimimus. He concluded that herbivory was more likely.[10]

The rock facies of the Nemegt Formation suggest the presence of stream and river channels, mudflats, and shallow lakes. Sediments also indicate a rich habitat existed, offering diverse food in abundant amounts that could sustain massive Cretaceous dinosaurs.[11]

In popular culture

Gallimimus was featured in one scene of the 1993 film, Jurassic Park.[12] In the scene, they are shown moving in unison like a flock of birds,[13] a fact noted by the character Alan Grant (played by Sam Neill).[14]

See also

References

- ↑ Makovicky (2009).

- ↑ Paul (1988).

- 1 2 Osmolska, H.; Roniewicz, E.; Barsbold, R. (1972). "A NEW DINOSAUR, GALLIMIMUS BULLATUS N. GEN. , N. SP. (ORNITHOMIMIDAE) FROM THE UPPER CRETACEOUS OF MONGOLIA.". Palaeontologia Polonica. 27: 103–143.

- 1 2 "Abstract," in Hurum (2001). Page 34.

- ↑ "Abstract," in Hurum (2001). Page 35.

- ↑ Kielan-Jaworowska Z. and Kowalski, K., 1965, "Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expeditions to the Gobi Desert in 1963 and 1964", Bulletin de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences, Cl. II 13(3), 175-179

- ↑ Kobayashi and Barsbold (2006).

- ↑ Xu, L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Lü, J.; Lee, Y. N.; Liu, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Zhang, X.; Jia, S.; Zhang, J. (2011). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with North American affinities from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation in Henan Province of China". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 213. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.004.

- ↑ Norell, et al. (2001).

- ↑ Barrett (2005).

- ↑ Novacek, M. (1996). Dinosaurs of the Flaming Cliffs. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group Inc. New York, New York. ISBN 978-0-385-47775-8

- ↑ Entertainment (2015-06-12). "How 'Jurassic World' dinosaurs looked in real life". Business Insider. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- ↑ http://www.dinosaurhome.com/jurassic-park-got-something-right-again-58.html

- ↑ "Dr. Alan Grant (Character) quotes".

Bibliography

- Barrett, P. M. (2005). "The diet of ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria)." Palaeontology, 48: 347-358.

- Hurum, J. 2001. Lower jaw of Gallimimus bullatus. pp. 34–41. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Ed.s Tanke, D. H., Carpenter, K., Skrepnick, M. W. Indiana University Press.

- Kobayashi, Y. and Barsbold, R. (2006). "Ornithomimids from the Nemegt Formation of Mongolia." Journal of the Paleontological Society of Korea, 22(1): 195-207.

- Norell, M. A., Makovicky, P., and Currie, P. J. (2001). "The beaks of ostrich dinosaurs." Nature, 412: 873-874.

- Peter J. Makovicky, Daqing Li, Ke-Qin Gao, Matthew Lewin, Gregory M. Erickson & Mark A. Norell. (2009). "A giant ornithomimosaur from the Early Cretaceous of China". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1679): 211-217. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0236

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 393. ISBN 0-671-61946-2.