Genome editing

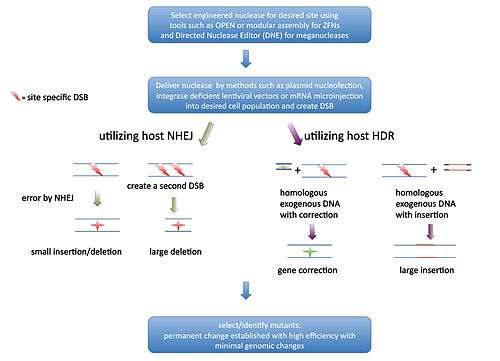

Genome editing, or genome editing with engineered nucleases (GEEN) is a type of genetic engineering in which DNA is inserted, deleted or replaced in the genome of a living organism using engineered nucleases, or "molecular scissors." These nucleases create site-specific double-strand breaks (DSBs) at desired locations in the genome. The induced double-strand breaks are repaired through nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homologous recombination (HR), resulting in targeted mutations ('edits').

There are currently four families of engineered nucleases being used: meganucleases, zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription activator-like effector-based nucleases (TALEN), and the CRISPR-Cas system.[1][2][3][4]

Genome editing was selected by Nature Methods as the 2011 Method of the Year.[5] The CRISPR-Cas system was selected by Science as 2015 Breakthrough of the Year.[6]

Concept

A common approach in modern biological research is to modify the DNA sequence (genotype) of an organism (or a single cell) and observe the impact of this change on the organism (phenotype). This approach is called reverse genetics and its significance for modern biology lies in its relative simplicity. This method contrasts with that of forward genetics, where a new phenotype is first observed and then its genetic basis is studied. This course is more complex because phenotypic changes are often a result of multiple genetic interactions.

Among the key requirements of reverse genetic analysis is the ability to modify the DNA sequence of the target organism. This can be achieved by:

- site-directed mutagenesis employing either phage- or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-mediated methods and oligonucleotides containing the desired mutation.[7] These methods are most useful in organisms with straightforward methods for the introduction and selection of genes of interest, such as bacteria and yeast.[8]

- recombination based methods that utilize the natural ability of cells to exchange DNA between its own genetic information and an exogenous DNA. These methods have been made possible in yeast and mice.

These approaches have several drawbacks:

- PCR- and phage-mediated approaches are less successful in more complex organisms such as mammals, where delivery becomes more difficult.

- They also require stringent selection steps and thus the addition of selection-specific sequences, along with those incorporated into the DNA.

- Recombination-based methods can be quite inefficient - e.g. in mouse embryonic stem cells treated with donor DNA, only 1 in a million DNA molecules was incorporated at the desired position.[9]

The use of other mutagenic techniques (such as P-element transgenesis in Drosophila) also has limitations, the major one being the randomness of incorporation and the possibility of affecting other genes and expression patterns.

Hence, genome editing with engineered nucleases is a promising new approach. This rapidly evolving technology overcomes these shortcomings and uses relatively simple concepts.

Double stranded breaks and their repair

Fundamental to the use of nucleases in genome editing is the concept of DNA double stranded break (DSB) repair mechanisms. Two of the known DSB repair pathways that are essentially functional in all organisms are the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology directed repair (HDR).

NHEJ uses a variety of enzymes to directly join the DNA ends in a double-strand break. In contrast, in HDR, a homologous sequence is utilized as a template for regeneration of missing DNA sequence at the break point. The natural properties of these pathways form the very basis of nucleases based genome editing.

NHEJ is error-prone, and has been shown to cause mutations at the repair site in approximately 50% of DSB in mycobacteria,[10] and also its low fidelity has been linked to mutational accumulation in leukemias.[11] Thus if one is able to create a DSB at a desired gene in multiple samples, it is very likely that mutations will be generated at that site in some of the treatments because of errors created by the NHEJ infidelity.

On the other hand, the dependency of HDR on a homologous sequence to repair DSBs can be exploited by inserting a desired sequence within a sequence that is homologous to the flanking sequences of a DSB which, when used as a template by HDR system, would lead to the creation of the desired change within the genomic region of interest.

Despite the distinct mechanisms, the concept of the HDR based gene editing is in a way similar to that of homologous recombination based gene targeting. However, the rate of recombination is increased by at least three orders of magnitude when DSBs are created and HDR is at work thus making the HDR based recombination much more efficient and eliminating the need for stringent positive and negative selection steps.[12] So based on these principles if one is able to create a DSB at a specific location within the genome, then the cell’s own repair systems will help in creating the desired mutations.

Site-specific double stranded breaks

Creation of a DSB in DNA should not be a challenging task as the commonly used restriction enzymes are capable of doing so. However, if genomic DNA is treated with a particular restriction endonuclease many DSBs will be created. This is a result of the fact that most restriction enzymes recognize a few base pairs on the DNA as their target and very likely that particular base pair combination will be found in many locations across the genome. To overcome this challenge and create site-specific DSB, three distinct classes of nucleases have been discovered and bioengineered to date. These are the Zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs), transcription-activator like effector nucleases (TALEN) and meganucleases. Below is a brief overview and comparison of these enzymes and the concept behind their development.

Current engineered nucleases

Meganucleases, found commonly in microbial species, have the unique property of having very long recognition sequences (>14bp) thus making them naturally very specific.[13][14] This can be exploited to make site-specific DSB in genome editing; however, the challenge is that not enough meganucleases are known, or may ever be known, to cover all possible target sequences. To overcome this challenge, mutagenesis and high throughput screening methods have been used to create meganuclease variants that recognize unique sequences.[14] Others have been able to fuse various meganucleases and create hybrid enzymes that recognize a new sequence.[15] Yet others have attempted to alter the DNA interacting aminoacids of the meganuclease to design sequence specific meganucelases in a method named rationally designed meganuclease (US Patent 8,021,867 B2).

Meganucleases have the benefit of causing less toxicity in cells than methods such as ZFNs, likely because of more stringent DNA sequence recognition;[14] however, the construction of sequence-specific enzymes for all possible sequences is costly and time consuming, as one is not benefiting from combinatorial possibilities that methods such as ZFNs and TALEN-based fusions utilize.

As opposed to meganucleases, the concept behind ZFNs and TALEN technology is based on a non-specific DNA cutting enzyme, which can then be linked to specific DNA sequence recognizing peptides such as zinc fingers and transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs).[16] The key to this was to find an endonuclease whose DNA recognition site and cleaving site were separate from each other, a situation that is not common among restriction enzymes.[16] Once this enzyme was found, its cleaving portion could be separated which would be very non-specific as it would have no recognition ability. This portion could then be linked to sequence recognizing peptides that could lead to very high specificity. A restriction enzyme with such properties is FokI. Additionally FokI has the advantage of requiring dimerization to have nuclease activity and this means the specificity increases dramatically as each nuclease partner would recognize a unique DNA sequence. To enhance this effect, FokI nucleases have been engineered that can only function as heterodimers and have increased catalytic activity.[17] The heterodimer functioning nucleases would avoid the possibility of unwanted homodimer activity and thus increase specificity of the DSB. Although the nuclease portions of both ZFNs and TALEN constructs have similar properties, the difference between these engineered nucleases is in their DNA recognition peptide. ZFNs rely on Cys2-His2 zinc fingers and TALEN constructs on TALEs. Both of these DNA recognizing peptide domains have the characteristic that they are naturally found in combinations in their proteins. Cys2-His2 Zinc fingers typically happen in repeats that are 3 bp apart and are found in diverse combinations in a variety of nucleic acid interacting proteins such as transcription factors. TALEs on the other hand are found in repeats with a one-to-one recognition ratio between the amino acids and the recognized nucleotide pairs. Because both zinc fingers and TALEs happen in repeated patterns, different combinations can be tried to create a wide variety of sequence specificities.[13] Zinc fingers have been more established in these terms and approaches such as modular assembly (where Zinc fingers correlated with a triplet sequence are attached in a row to cover the required sequence), OPEN (low-stringency selection of peptide domains vs. triplet nucleotides followed by high-stringency selections of peptide combination vs. the final target in bacterial systems), and bacterial one-hybrid screening of zinc finger libraries among other methods have been used to make site specific nucleases.

One recent improvement combines the DNA binding specificity of TALEs with the nuclease specificity of meganucleases; these "megaTALs" are compatible with all current technologies and may represent improvements on existing methods.[18]

Precision of engineered nucleases

Because off-target activity of an active nuclease would have potentially dangerous consequences at the genetic and organismal levels, the precision of meganucleases, ZFNs, CRISPR, and TALEN-based fusions has been an active area of research. While variable figures have been reported, ZFNs tend to have more cytotoxicity than TALEN methods or RNA-guided nucleases, while TALEN and RNA-guided approaches tend to have the greatest efficiency and fewer off-target effects.[19] Based on the maximum theoretical distance between DNA binding and nuclease activity, TALEN approaches result in the greatest precision.[4]

Applications

Over the past decade, efficient genome editing has been developed for a wide range of experimental systems ranging from plants to animals, often beyond clinical interest, and the method holds a promising future in becoming a standard experimental strategy in research labs.[20] The recent generation of rat, zebrafish, maize and tobacco ZFN-mediated mutants and the improvements in TALEN-based approaches testify to the significance of the methods, and the list is expanding rapidly. Genome editing with engineered nucleases will likely contribute to many fields of life sciences from studying gene functions in plants and animals to gene therapy in humans. For instance, the field of synthetic biology which aims to engineer cells and organisms to perform novel functions, is likely to benefit from the ability of engineered nuclease to add or remove genomic elements and therefore create complex systems.[20] In addition, gene functions can be studied using stem cells with engineered nucleases.

Listed below are some specific tasks this method can carry out:

- Targeted gene mutation

- Creating chromosome rearrangement

- Study gene function with stem cells

- Transgenic animals

- Endogenous gene labeling

- Targeted transgene addition

Targeted gene modification in plants

Genome editing using meganucleases,[21] ZFNs, and TALEN provides a new strategy for genetic manipulation in plants and are likely to assist in the engineering of desired plant traits by modifying endogenous genes. For instance, site-specific gene addition in major crop species can be used for 'trait stacking' whereby several desired traits are physically linked to ensure their co-segregation during the breeding processes.[17] Progress in such cases have been recently reported in Arabidopsis thaliana[22][23][24] and Zea mays. In Arabidopsis thaliana, using ZFN-assisted gene targeting, two herbicide-resistant genes (tobacco acetolactate synthase SuRA and SuRB) were introduced to SuR loci with as high as 2% transformed cells with mutations.[25] In Zea mays, disruption of the target locus was achieved by ZFN-induced DSBs and the resulting NHEJ. ZFN was also used to drive herbicide-tolerance gene expression cassette (PAT) into the targeted endogenous locus IPK1 in this case.[26] Such genome modification observed in the regenerated plants has been shown to be inheritable and was transmitted to the next generation.[26]

In addition, TALEN-based genome engineering has been extensively tested and optimized for use in plants.[27] TALEN fusions have also been used to improve the quality of soybean oil products[28] and to increase the storage potential of potatoes[29]

Several optimizations need to be made in order to improve editing plant genomes using ZFN-mediated targeting.[30] These include the reliable design and subsequent test of the nucleases, the absence of toxicity of the nucleases, the appropriate choice of the plant tissue for targeting, the routes of introduction or induction of enzyme activity, the lack of off-target mutagenesis, and a reliable detection of mutated cases.[30]

Gene therapy

The ideal gene therapy practice is that which replaces the defective gene with a normal allele at its natural location. This is advantageous over a virally delivered gene as there is no need to include the full coding sequences and regulatory sequences when only a small proportions of the gene needs to be altered as is often the case.[31] The expression of the partially replaced genes is also more consistent with normal cell biology than full genes that are carried by viral vectors.

Gene targeting through ZFNs or TALEN-based approaches can also be used to modify defective genes at their endogenous chromosomal locations. Examples include the treatment of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) by ex vivo gene correction with DNA carrying the interleukin-2 receptor common gamma chain (IL-2Rγ)[32] and the correction of Xeroderma pigmentosum mutations in vitro using TALEN.[33] Insertional mutagenesis by the retroviral vector genome induced leukemia in some patients, a problem that is predicted to be avoided by these technologies. However, ZFNs may also cause off-target mutations, in a different way from viral transductions. Currently many measures are taken to improve off-target detection and ensure safety before treatment.

Recently, Sangamo BioSciences (SGMO) introduced the Delta 32 mutation (a suppressor of CCR5 gene which is a co-receptor for HIV-1 entry into T cells therefore enabling HIV infection) using Zinc Finger Nuclease (ZFN). Their results were presented at the 51st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) held in Chicago from September 17–20, 2011.[34] Researchers at SGMO mutated CCR5 in CD4+ T cells and subsequently produced an HIV-resistant T-cell population.[35]

Gene editing is used to generate modified custom immune cells. For example, recent report indicated that T cells could be modified to inactivate the glucocorticoid receptor; the resulting immune cells are fully functional but resistant to the effects of commonly used corticosteroids.[36] Similarly, scientists at Cellectis recently generated custom T-cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors using TALEN technology.[37] These T-cells can be engineered to be resistant to anti-cancer drugs and to invoke immune responses against targets of interest.[38]

The first clinical use of TALEN-based genome editing was in the treatment of CD19+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia in an 11-month old child.[39] Modified donor T cells were engineered to attack the leukemia cells, to be resistant to Alemtuzumab, and to evade detection by the host immune system after introduction. A few weeks after therapy, the patient's condition improved. Though physicians are cautious, the patient has been in remission for several months following treatment.[40][41]

Prospects and limitations

In the future, an important goal of research into genome editing with engineered nucleases must be the improvement of the safety and specificity of the nucleases. For example, improving the ability to detect off-target events can improve our ability to learn about ways of preventing them. In addition, zinc-fingers used in ZFNs are seldom completely specific, and some may cause a toxic reaction. However, the toxicity has been reported to be reduced by modifications done on the cleavage domain of the ZFN.[31]

In addition, research by Dana Carroll into modifying the genome with engineered nucleases has shown the need for better understanding of the basic recombination and repair machinery of DNA. In the future, a possible method to identify secondary targets would be to capture broken ends from cells expressing the ZFNs and to sequence the flanking DNA using high-throughput sequencing.[31]

Genome editing occurs also as a natural process without artificial genetic engineering. The agents that are competent to edit genetic codes are viruses or subviral RNA-agents.[42]

Lastly, although GEEN has higher efficiency than many other methods in reverse genetics, it is still not highly efficient; in many cases less than half of the treated populations obtain the desired changes.[25] For example, when one is planning to use the cell's NHEJ to create a mutation, the cell's HDR systems will also be at work correcting the DSB with lower mutational rates.

See also

- Genome engineering

- CRISPR/Cpf1

- TALEN

- NgAgo, a ssDNA-guided Argonaute endonuclease

Further reading

- Customized Human Genes Scientific American articles

- Connor, Steve (25 April 2014). "Scientific split - the human genome breakthrough dividing former colleagues". The Independent. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

References

- ↑ Esvelt, KM.; Wang, HH. (2013). "Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology.". Mol Syst Biol. 9 (1): 641. doi:10.1038/msb.2012.66. PMC 3564264

. PMID 23340847.

. PMID 23340847. - ↑ Tan, WS.; Carlson, DF.; Walton, MW.; Fahrenkrug, SC.; Hackett, PB. (2012). "Precision editing of large animal genomes.". Adv Genet. 80: 37–97. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-404742-6.00002-8. PMC 3683964

. PMID 23084873.

. PMID 23084873. - ↑ Puchta, H.; Fauser, F. (2013). "Gene targeting in plants: 25 years later.". Int. J. Dev. Biol. 57: 629–637. doi:10.1387/ijdb.130194hp.

- 1 2 Boglioli, Elsy; Richard, Magali. "Rewriting the book of life: a new era in precision genome editing" (PDF). Boston Consulting Group. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Method of the Year 2011. Nat Meth 9 (1), 1-1.

- ↑ http://www.sciencemag.org/topic/2015-breakthrough-year

- ↑ Ling, M. M.; Robinson, B. H. (1997-12-15). "Approaches to DNA mutagenesis: an overview". Analytical Biochemistry. 254 (2): 157–178. doi:10.1006/abio.1997.2428. ISSN 0003-2697. PMID 9417773.

- ↑ Storici, Francesca; Lewis, L. Kevin; Resnick, Michael A. (2001-08-01). "In vivo site-directed mutagenesis using oligonucleotides". Nature Biotechnology. 19 (8): 773–776. doi:10.1038/90837.

- ↑ Capecchi, M., Altering the genome by homologous recombination" Science 244 (4910), 1288-1292 (1989).

- ↑ Gong, C. et al., Mechanism of nonhomologous end-joining in mycobacteria: a low-fidelity repair system driven by Ku, ligase D and ligase C. Nat Struct Mol Biol 12 (4), 304-312 (2005).

- ↑ Feyruz Virgilia, R., DNA double strand breaks (DSB) and non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathways in human leukemia. Cancer Letters 193 (1), 1-9 (2003).

- ↑ Maria, J., Genetic manipulation of genomes with rare-cutting endonucleases" Trends in Genetics 12 (6), 224-228 (1996).

- 1 2 de Souza, N., Primer: genome editing with engineered nucleases. Nat Meth 9 (1), 27-27 (2011).

- 1 2 3 Smith, J. et al., A combinatorial approach to create artificial homing endonucleases cleaving chosen sequences" Nucleic Acids Research 34 (22), e149 (2006).

- ↑ Chevalier, B.S. et al., Design, Activity, and Structure of a Highly Specific Artificial Endonuclease" Molecular Cell 10 (4), 895-905 (2002).

- 1 2 Baker, M., Gene-editing nucleases. Nat Meth 9 (1), 23-26 (2012).

- 1 2 Urnov, F.D., Rebar, E.J., Holmes, M.C., Zhang, H.S., & Gregory, P.D., Genome editing with engineered zinc finger nucleases" Nat Rev Genet 11 (9), 636-646 (2010).

- ↑ Boissel, Sandrine; Jarjour, Jordan; Astrakhan, Alexander; Adey, Andrew; Gouble, Agnès; Duchateau, Philippe; Shendure, Jay; Stoddard, Barry L.; Certo, Michael T. (2014-02-01). "megaTALs: a rare-cleaving nuclease architecture for therapeutic genome engineering". Nucleic Acids Research. 42 (4): 2591–2601. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1224. ISSN 1362-4962. PMC 3936731

. PMID 24285304.

. PMID 24285304. - ↑ Kim, Hyongbum; Kim, Jin-Soo (2014-04-02). "A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases". Nature Reviews Genetics. 15 (5): 321–334. doi:10.1038/nrg3686.

- 1 2 McMahon, M.A., Rahdar, M., & Porteus, M., Gene editing: not just for translation anymore. Nat Meth 9 (1), 28-31 (2012).

- ↑ Arnould, S.; Delenda, C.; Grizot, S.; Desseaux, C.; Pâques, F.; Silva, G. H.; Smith, J. (2011-01-01). "The I-CreI meganuclease and its engineered derivatives: applications from cell modification to gene therapy". Protein engineering, design & selection: PEDS. 24 (1-2): 27–31. doi:10.1093/protein/gzq083. ISSN 1741-0134. PMID 21047873.

- ↑ Townsend, J.A. et al., High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases" Nature 459 (7245), 442-445 (2009).

- ↑ Zhang, F. et al., High frequency targeted mutagenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana using zinc finger nucleases" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (26), 12028-12033 (2009).

- ↑ Osakabe, K., Osakabe, Y., & Toki, S., Site-directed mutagenesis in Arabidopsis using custom-designed zinc finger nucleases" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (26), 12034-12039 (2010).

- 1 2 Townsend, J.A. et al., High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases" Nature 459 (7245), 442-445 (2009).

- 1 2 Shukla, V.K. et al., Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases" Nature 459 (7245), 437-U156 (2009).

- ↑ Zhang, Yong; Zhang, Feng; Li, Xiaohong; Baller, Joshua A.; Qi, Yiping; Starker, Colby G.; Bogdanove, Adam J.; Voytas, Daniel F. (2013-01-01). "Transcription activator-like effector nucleases enable efficient plant genome engineering". Plant Physiology. 161 (1): 20–27. doi:10.1104/pp.112.205179. ISSN 1532-2548. PMC 3532252

. PMID 23124327.

. PMID 23124327. - ↑ Haun, William; Coffman, Andrew; Clasen, Benjamin M.; Demorest, Zachary L.; Lowy, Anita; Ray, Erin; Retterath, Adam; Stoddard, Thomas; Juillerat, Alexandre (2014-09-01). "Improved soybean oil quality by targeted mutagenesis of the fatty acid desaturase 2 gene family". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 12 (7): 934–940. doi:10.1111/pbi.12201. ISSN 1467-7652. PMID 24851712.

- ↑ Clasen, Benjamin M.; Stoddard, Thomas J.; Luo, Song; Demorest, Zachary L.; Li, Jin; Cedrone, Frederic; Tibebu, Redeat; Davison, Shawn; Ray, Erin E. (2015-04-07). "Improving cold storage and processing traits in potato through targeted gene knockout". Plant Biotechnology Journal. doi:10.1111/pbi.12370. ISSN 1467-7652. PMID 25846201.

- 1 2 Puchta, H. & Hohn, B., Breaking news: Plants mutate right on target" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (26), 11657-11658 (2010).

- 1 2 3 Carroll, D., Progress and prospects: Zinc-finger nucleases as gene therapy agents. Gene Ther 15 (22), 1463-1468 (2008).

- ↑ Lombardo, A. et al., Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery. Nat Biotech 25 (11), 1298-1306 (2007).

- ↑ Dupuy, Aurélie; Valton, Julien; Leduc, Sophie; Armier, Jacques; Galetto, Roman; Gouble, Agnès; Lebuhotel, Céline; Stary, Anne; Pâques, Frédéric (2013-11-13). "Targeted Gene Therapy of Xeroderma Pigmentosum Cells Using Meganuclease and TALEN™". PLoS ONE. 8 (11): e78678. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078678. PMC 3827243

. PMID 24236034.

. PMID 24236034. - ↑ Sangamo BioSciences Announces Presentation of Groundbreaking Clinical Data From ZFN Therapeutic for HIV/AIDS at ICAAC 2011 (2011).

- ↑ Perez, E.E. et al., Establishment of HIV-1 resistance in CD4+ T cells by genome editing using zinc-finger nucleases. Nat Biotech 26 (7), 808-816 (2008).

- ↑ Menger, Laurie; Gouble, Agnes; Marzolini, Maria A. V.; Pachnio, Annette; Bergerhoff, Katharina; Henry, Jake Y.; Smith, Julianne; Pule, Martin; Moss, Paul (2015-01-01). "TALEN-mediated genetic inactivation of the glucocorticoid receptor in cytomegalovirus-specific T cells". Blood: blood–2015–08–664755. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-08-664755. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 26508783.

- ↑ Valton, Julien; Guyot, Valérie; Marechal, Alan; Filhol, Jean-Marie; Juillerat, Alexandre; Duclert, Aymeric; Duchateau, Philippe; Poirot, Laurent (2015-09-01). "A Multidrug-resistant Engineered CAR T Cell for Allogeneic Combination Immunotherapy". Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 23 (9): 1507–1518. doi:10.1038/mt.2015.104. ISSN 1525-0024. PMID 26061646.

- ↑ Poirot, Laurent; Philip, Brian; Schiffer-Mannioui, Cécile; Clerre, Diane Le; Chion-Sotinel, Isabelle; Derniame, Sophie; Bas, Cécile; Potrel, Pierrick; Lemaire, Laetitia (2015-07-16). "Multiplex genome edited T-cell manufacturing platform for "off-the-shelf" adoptive T-cell immunotherapies". Cancer Research: canres.3321.2014. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3321. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 26183927.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (2015-11-05). "A Cell Therapy Untested in Humans Saves a Baby With Cancer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ "Paper: First Clinical Application of Talen Engineered Universal CAR19 T Cells in B-ALL". ash.confex.com. Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ "Science Magazine: Baby's leukemia recedes after novel cell therapy". Retrieved 2015-11-30.

- ↑ Witzany, G (2011). "The agents of natural genome editing". J Mol Cell Biol. 3 (3): 181–189. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjr005. PMID 21459884.