Georgian Affair

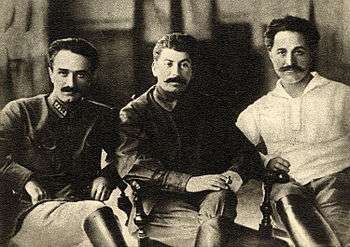

The Georgian Affair of 1922 (Russian: Грузинское дело) was a political conflict within the Soviet leadership about the way in which social and political transformation was to be achieved in the Georgian SSR. The dispute over Georgia, which arose shortly after the forcible Sovietization of the country and peaked in the latter part of 1922, involved local Georgian Bolshevik leaders, led by Filipp Makharadze and Budu Mdivani, on one hand, and their de facto superiors from the Russian SFSR, particularly Joseph Stalin and Grigol Ordzhonikidze, on the other hand. The content of this dispute was complex, involving the Georgians’ desire to preserve autonomy from Moscow and the differing interpretations of Bolshevik nationality policies, and especially those specific to Georgia. One of the main points at issue was Moscow’s decision to amalgamate Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan into Transcaucasian SFSR, a move that was staunchly opposed by the Georgian leaders who urged for their republic a full-member status within the Soviet Union.

The affair was a critical episode in the power struggle surrounding the sick Vladimir Lenin whose support Georgians sought to obtain. The dispute ended with the victory of the Stalin-Ordzhonikidze line and resulted in the fall of the Georgian moderate Communist government. It also contributed to a final break between Lenin and Stalin, and inspired Lenin’s last major writings.[1]

Background

The Soviet rule in Georgia was established by the Soviet Red Army during the February-March 1921 military campaign that was largely engineered by the two influential Georgian-born Soviet Russian officials, Joseph Stalin, then People's Commissar for Nationalities for the RSFSR, and Grigol Ordzhonikidze, head of the Transcaucasian Regional Committee (Zaikkraikom) of the Russian Communist Party. Disagreements among the Bolsheviks about the fate of Georgia preceded the Red Army invasion. While Stalin and Ordzhonikidze urged the immediate Sovietization of independent Georgia led by the Menshevik-dominated government, Trotsky favored "a certain preparatory period of work inside Georgia, in order to develop the uprising and later come to its aid." Lenin was unsure about the outcome of the Georgian campaign, fearful of the international consequences and the possible crisis with Kemalist Turkey. Lenin finally gave his consent, on February 14, 1921, to the intervention in Georgia, but later repeatedly complained about the lack of precise and consistent information from the Caucasus.[2] Well aware of widespread opposition to the newly established Soviet rule, Lenin favored a reconciliatory policy with Georgian intelligentsia and peasants who remained hostile to the militarily imposed regime. However, many Communists found it difficult to abandon the methods used against their opposition during the Russian Civil War and make adjustment to the more flexible policy. For moderates like Filipp Makharadze Lenin’s approach was a reasonable way to secure for Soviet power a broad base of support. They advocated tolerance toward the Menshevik opposition, greater democracy within the party, gradual land reform, and above all, respect for national sensitivities and Georgia’s sovereignty from Moscow. Communists like Ordzhonikidze and Stalin pursued a more hard-line policy; they sought to eliminate completely political opposition and centralize party control over the newly Sovietized republics.[3][2]

"National deviationism" vs. "Great Russian nationalism"

Conflict soon broke out between the moderate and hard-line Georgian Bolshevik leaders. The dispute was preceded by Stalin’s ban on formation of the national Red Army of Georgia, and subordination of all local workers’ organizations and trade unions to the Bolshevik party committees. Dissatisfied by the Soviet Georgian government’s moderate treatment of the political opposition and its desire to retain sovereignty from Moscow, Stalin arrived in Tbilisi, capital of Georgia, in early July 1921. After summoning a workers' assembly, Stalin delivered a speech outlining a program aimed at elimination of local nationalism, but was booed by the crowd and received hostile silence from his colleagues.[4] Within the days that followed, Stalin removed the Georgian Revolutionary committee chief Makharadze for inadequate firmness and replaced him with Polikarp Mdivani, ordering local leaders to "crush the hydra of nationalism."[3] Makharadze’s supporters, including the Georgian Cheka chief Kote Tsintsadze and his lieutenants, were also sacked and replaced with more ruthless officers Kvantaliani, Atarbekov, and Lavrentiy Beria.

Within less than a year, however, Stalin was in open conflict with Mdivani, and his associates. One of the most important points at issue was the question of Georgia’s status in the projected union of Soviet republics. While Moscow’s envoys, led by Grigol Ordzhonikidze and strongly backed by Stalin, insisted that all three Transcaucasian republics – Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia – join the Soviet Union together as one federative republic, the Georgians wanted their country to retain an individual identity and enter the union as a full member rather than as part of a single Transcaucasian SFSR. Stalin and his henchmen accused the local Georgian Communists of selfish nationalism and labeled them as "national deviationists". On their part, the Georgians responded with charges of "Great Russian chauvinism". Lenin suddenly upheld Stalin’s position and expressed his strong support for the political and economic integration of the Transcaucasian republics, informing the Georgian leaders that he rejected their criticism of Moscow's bullying tactics.

The conflict peaked in November 1922, when Ordzhonikidze resorted to physical violence with a member of the Mdivani group and struck him during a verbal confrontation.[5] The Georgian leaders complained to Lenin and presented a long list of abuses, including the notorious incident involving Ordzhonikidze.

Lenin’s involvement

Lenin was no longer able to overlook the bitterness of the conflict in Georgia and unleashed his criticism upon Ordzhonikidze. In late November 1922, he dispatched the VeCheka chief Dzerzhinsky to Tiflis to investigate the matter. Dzerzhinsky sympathized with Stalin and Ordzhonikidze and, hence, tried to give Lenin a significantly smoothened picture of their activities in his report.[3] However, Lenin's doubts about the conduct of Stalin and his allies around the Georgian question mounted. He was also afraid of negative outcry that might ensue abroad and in other Soviet republics. In late December 1922, Lenin accepted that both Ordzhonikidze and Stalin were guilty of the imposition of Great Russian nationalism upon non-Russian nationalities.[6] He now considered Stalin and his forceful centralizing policy increasingly dangerous and decided to dissociate himself at once from his protégé.

Nevertheless, Lenin’s misgivings over the Georgian problem were not fundamental, and as his health deteriorated, the Georgian leaders were left without any major ally, watching Georgia being pressed into the Transcaucasian federation that signed a treaty with the Russian SFSR, Ukraine and Belarus, joining them all in a new Soviet Union on December 30, 1922.[7]

The Politburo decision of 25 January 1923 concerning the removal of Mdivani and his associates from Georgia represented a conclusive victory for Ordzhonikidze and his backers.[1]

The end of the affair

On March 5, 1923, Lenin broke off personal relations with Stalin. He attempted to enlist Leon Trotsky to take over the Georgian problem, and began preparing three notes and a speech, where he would announce to the Party Congress that Stalin would be removed as General Secretary.[8] However, on March 9, 1923 Lenin suffered a third stroke, which would eventually lead to his death. Trotsky declined to confront Stalin on the issue probably due to his long-held prejudice against Georgia as a Menshevik stronghold,[6] At the 12th Party Congress in April 1923, the Georgian Communists found themselves isolated. With Lenin’s notes suppressed, every word uttered from the platform against Georgian or Ukrainian nationalism was greeted with stormy applause, while the mildest allusion to Great Russian chauvinism was received in stony silence.[9]

Thus, Lenin’s illness, Stalin’s increasing influence in the party and his ascent toward full power, coupled with the sidelining of Leon Trotsky led to the marginalization of the decentralist forces within the Georgian Communist Party.[10]

The affair held back the careers of the Georgian Old Bolsheviks, but Ordzhonikidze's reputation also suffered and he was soon recalled from the Caucasus.[1] Mdivani and his associates were removed to minor posts, but they were not actively molested until the late 1920s. Most of them were later executed during the Great Purge of the 1930s. Another major consequence of the defeat of Georgian "national deviationists" was the intensification of political repressions in Georgia, leading to an armed rebellion in August 1924 and the ensuing Red Terror which took several thousands of lives.

References

- 1 2 3 Smith, Jeremy (1998). "The Georgian Affair of 1922. Policy Failure, Personality Clash or Power Struggle?". Europe-Asia Studies. 50 (3): 519–544. doi:10.1080/09668139808412550.

- 1 2 Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation: 2nd edition, pp. 210-212. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20915-3

- 1 2 3 Knight, Ami W. (1993), Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant, p . 26-27. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, ISBN 0-691-01093-5

- ↑ Lang, David Marshall (1962). A Modern History of Georgia, p. 238. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- ↑ Kort, M (2001), The Soviet Colossus, p.154. M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-0396-9

- 1 2 Thatcher, Ian D. (2003), Trotsky, p. 122. Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23250-3

- ↑ Alan Ball, 'Building a new state and society: NEP, 1921-1928', in: R.G. Suny, The Cambridge History of Russia, vol. III: The Twentieth Century (Cambridge 2006), p. 175.

- ↑ McNeal, Robert H. (1959), Lenin's Attack on Stalin: Review and Reappraisal, American Slavic and East European Review, 18 (3): 295-314

- ↑ Lang (1962), p. 243.

- ↑ Cornell, Svante E. (2002), Autonomy and Conflict: Ethnoterritoriality and Separatism in the South Caucasus – Case in Georgia, pp. 141-144. Department of Peace and Conflict Research, University of Uppsala, ISBN 91-506-1600-5

- Jones, Stephen F. (October 1988). "The Establishment of Soviet Power in Transcaucasia: The Case of Georgia 1921-1928". Soviet Studies. 40, No. 4 (4): 616–639. JSTOR 151812.

- Ogden, Dennis George (1978), National Communism in Georgia: 1921-1923, The University of Michigan (doctoral dissertation)