Marxism and the National Question

Marxism and the National Question (Russian: Марксизм и национальный вопрос) is a short work of Marxist theory written by Joseph Stalin in January 1913 while living in Vienna. First published as a pamphlet and frequently reprinted, the essay by the ethnic Georgian Stalin was regarded as a seminal contribution to Marxist analysis of the nature of nationality and helped to establish his reputation as an expert on the topic. Stalin would later become the first People's Commissar of Nationalities following the victory of the Bolshevik Party in the October Revolution of 1917.

Although it did not appear in the various English-language editions of Stalin's Selected Works, which began to appear in 1928, Marxism and the National Question was widely republished from 1935 as part of the topical collection Marxism and the National and Colonial Question.

Content summary

With his thesis reduced to a single line, Stalin concluded, "A nation is a historically constituted, stable community of people, formed on the basis of a common language, territory, economic life, and psychological make-up manifested in a common culture." In defining a nation in this manner, Stalin took on the ideas of Otto Bauer, for whom a nation was primarily a manifestation of character and culture.[1] He instead followed Karl Kautsky in asserting the primacy of language, territory, and integrated economic life without formal acknowledgement of the source.[2]

Thus defined, Stalin took aim at the notion of "national–cultural autonomy," charging that the formulation was but a cloaked form of nationalism in socialist garb.[2] Stalin argued that such an approach would lead to the cultural and economic isolation of primitive nationalities and that the path forward should be the unification of various and sundry nations and nationalities into a unified stream of higher culture.[3]

Background

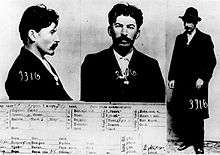

Ioseb Besarionis Dze Jugashvili (1878–1953), better known by his Anglicized party name Joseph Stalin, was an ethnic Georgian intellectual and Marxist revolutionary affiliated with the Bolshevik wing of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). Jugashvili regarded Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924) as a role model and intellectual beacon, and the young activist was sometimes jokingly called "Lenin's left foot" by his Georgian comrades.[4] Jugashvili did not just admire the exiled Lenin from afar through correspondence but had even met him personally, with the pair jointly attending the 1907 Congress of the RSDLP held in London as part of a 92-member Bolshevik delegation.[5]

From the time he left the seminary (one of the only higher educational channels available to Georgian intellectuals at that time), Jugashvili was a so-called "professional revolutionary", a paid employee of the Bolshevik party organization dedicated full time to revolutionary activity.[6] Prior to 1910, Jugashvili's main political activity took place in the Transcaucasian region of the Russian empire,[7] making a home in the Azerbaijani oil city of Baku from 1907.[8] Jugashvili's helped to organize Marxist study circles and worked as an agitator and journalist, writing for the Bolshevik party press.[9] He was a reasonably prolific writer during this period, producing no fewer than 56 articles, leaflets, and he preserved pieces of political correspondence.[10]

Despite the mass of his written output, Stalin's earliest writing was mainly topical and ephemeral, with only a series of newspaper articles written for the Bolshevik press in opposition to anarchism during the Russian Revolution of 1905 gaining permanence through republication as the pamphlet Anarchism or Socialism?[11] This first effort at writing a generalized work of Marxist theory in serial form was incomplete, as it was interrupted early in 1907 by Jugashvili's departure from Tiflis to London for the Bolshevik Congress there and by his subsequent move to Baku.[11] No additional substantial contribution to theory would be made until the writing of Marxism and the National Question in 1913.

Despite the paucity of substantial writing, Stalin was well regarded by the Bolshevik leaders in exile, and he was co-opted in absentia to the governing Central Committee of the now independent Bolshevik Party at the 1912 Party Conference held in Copenhagen.[12] Jugashvili, now known by his party name "Stalin,"[13] was at the same time named one of four members of a "Russian Bureau" for the day-to-day direction of the activity of the Bolshevik Party within the borders of the Russian empire by the émigré Copenhagen party conference.[12]

Writing

The actual writing of Marxism and the National Question began in November 1912, when Stalin traveled to Cracow, Poland to confer with Lenin on Bolshevik party business.[14] Lenin had published an article earlier that same month condemning nationalist fragmentation of the revolutionary movement, holding up as the disintegration of the Social Democratic Party of Austria into autonomous German, Czech, Polish, Ruthenian, Italian and Slovene groupings as a grim example.[15] Lenin feared a comparable shattering of the RSDLP along national lines and sought to crush the Austro-Marxist slogan of "national–cultural autonomy."[15]

Stalin, as an antinationalist Georgian with no fear of ethnic Russian domination of the RSDLP, was seen both as an expert on the current interrelationship of the various nationalities of Transcaucasia and as a potential national minority voice in favor of maintenance of a centralized and unified party organization.[1] Stalin was set on the task of writing a lengthy article for publication in the Bolshevik theoretical monthly Prosveshchenie (Enlightenment) detailing an official position on the matter.[1] Regarding Stalin's assignment to write such an article, Lenin wrote to novelist Maxim Gorky in February 1913:

"About nationalism, I fully agree with you that we have to bear down harder. We have here a wonderful Georgian who has undertaken to write a long article for Prosveshchenie after gathering all the Austrian and other materials. We will take care of this matter."[16]

The bulk of Stalin's writing took place during January 1913, in Vienna.[1]

Publication history

Marxism and the National Question was completed late in January 1913, with the author signing the work "K. Stalin."[17] The work first appeared in serial form in the Bolshevik magazine Prosveshchenie (Enlightenment), with installments appearing in the March, April, and May 1913 issues of that publication.[18] The original title of the work as it appeared in 1913 was Natsional'nye vopros is Sotsial-Demokratii (The National Question and the Social Democracy).[18] The three articles were combined for republication in pamphlet form as Natsional'nyi vopros i Marksizm (The National Question and Marxism) in 1914.[19]

Marxism and the National Question was not included in any one- or two-volume Russian version of Stalin's Selected Works (Voprosy Leninizma), which first appeared in 1926, or in any English-language translation of this book appearing from 1928 to 1954. However, the work was reprinted as the lead essay in a 1934 Russian topical collection, Markizm i natsional'no-kolonial'nyi vopros, and its English translations in the following year, Marxism and the National and Colonial Question. Two nearly simultaneous editions appeared in 1935, one published in Moscow and Leningrad by the Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the USSR (forerunner of the official Foreign Languages Publishing House) and another in New York under the imprint of International Publishers. The new title remained in print thereafter, throughout Stalin's lifetime.

Authorship controversy

Eager to denigrate his nemesis, in his 1941 biography of Stalin exiled Soviet leader Leon Trotsky intimated that primary credit for all that was worthy about Marxism and the National Question actually belonged to fellow Bolsheviks Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin. Trotsky wrote:

"Stalin's progress on his article is pictured for us with sufficient clarity. At first, leading conversations with Lenin in Cracow, the outlining of the dominating ideas and of the research material. Later, Stalin's journey to Vienna, into the hear of the 'Austrian school.' Since he did not know German, Stalin could not cope with his source material. But there was Bukharin, who unquestionably had a head for theory, knew languages, knew the literature of the subject, knew how to use documents. Bukharin...was under instructions from Lenin to help the 'splendid' but poorly educated Georgian. The logical construction of the article, not devoid of pedantry, is due most likely to the influence of Bukharin, who inclined toward professorial ways..."From Vienna Stalin returned with his material to Cracow. Here again came Lenin's turn, the turn of the attentive and tireless editor. The stamp of his thought and the traces of his pen are readily discoverable on every page. Certain phrases, mechanically incorporated by the author, or certain lines, obviously written in by the editor, seem unexpected or incomprehensible without reference to the corresponding works of Lenin....

"Zinoviev and Kamenev, who long lived side by side with Lenin, acquired not only his ideas but even his turns of phrase, even his handwriting. That can not be said about Stalin. Of course, he too lived by Lenin's ideas, but at a distance, away from him, and he used them only as he needed them for his own independent purposes. He was too sturdy, too stubborn, too dull and too organic, to acquire the literary methods of his teacher. That is why Lenin's corrections of his text, to quote the poet, look 'like bright patches on dilapidated tatters.'...

"The original manuscript with its corrections can, of course, be hidden. But it is impossible, in any way, to hide the hand of Lenin, as it is impossible to hide the fact that throughout all the years of his imprisonment and exile Stalin produced nothing which even remotely resembles the work he wrote in the course of a few weeks in Vienna and Cracow."[20]

This speculative charge by Trotsky has found its way into the historical literature, echoed by such Stalin biographers as Isaac Deutscher and Bertram D. Wolfe.[19] Other historians paying attention to the question have differed, with Robert H. McNeal concluding that while Lenin "certainly helped form Stalin's ideas on the nationality question before the essay of 1913 was composed" and "probably edited it for republication in 1914," at root "the work remains essentially Stalin's."[21] Stalin biographer Robert C. Tucker concurred that "there is no good reason to credit Lenin—as Trotsky did—with virtual authorship of the work."[22] He added that Stalin "needed little if any assistance in those important sections of the work that dealt with the Bund and the national question in the Transcaucasus."[23]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 152.

- 1 2 Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 153.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 154.

- ↑ R. Arsenidze, "Iz vospominanii o Staline" (Reminiscences of Stalin), Novyi zhurnal, no. 72 (June 1963), pg. 223; quoted in Robert C. Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, 1879–1929: A Study in History and Personality. New York: W.W. Norton, 1973; pg. 135.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 139.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 145.

- ↑ Robert H. McNeal, Stalin's Works: An Annotated Bibliography. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, 1967; pg. 10.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 138.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 144.

- ↑ The count of such items from the years before 1910 officially exceeded 100 although the attribution of some of these items is regarded by specialist historian Robert McNeal as dubious. See: McNeal, Stalin's Works, pg. 10.

- 1 2 Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 117.

- 1 2 Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 148.

- ↑ "Stalin" is a Russian-sounding pseudonym derived from the word stal', steel.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 150.

- 1 2 Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 151.

- ↑ V.I. Lenin, Polnoe sobranie sochinenii (Complete Collected Works). Moscow: Izdatel'stvo Politicheskoi Literatury, 1964; pg. 162. Quoted in Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 152.

- ↑ McNeal, Stalin's Works, pg. 42. The signature is apparently an amalgam of Jugashvili's two party names, the former pseudonym "Koba" and the new pseudonym "Koba."

- 1 2 McNeal, Stalin's Works, pg. 42.

- 1 2 McNeal, Stalin's Works, pg. 43.

- ↑ Leon Trotsky, Stalin: An Appraisal of the Man and His Influence. Charles Malamuth, trans. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1941; pp.157–159.

- ↑ McNeal, Stalin's Works, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pg. 155.

- ↑ Tucker, Stalin as Revolutionary, pp. 155–156.

Further reading

- N.N. Agrawal, "Lenin on National and Colonial Questions," Indian Journal of Political Science, vol. 17, no. 3 (July–Sept. 1956), pp. 207–240. In JSTOR

- Horace B. Davis, "Lenin and Nationalism: The Redirection of the Marxist Theory of Nationalism, 1903–1917," Science & Society, vol. 31, no. 2 (Spring 1967), pp. 164–185. In JSTOR

- Erich Hula, "The Nationalities Policy of the Soviet Union: Theory and Practice," Social Research, vol. 11, no. 2 (May 1944), pp. 168–201. In JSTOR

- Robert H. McNeal, "Trotsky's Interpretation of Stalin," Canadian Slavonic Papers, vol. 5 (1961), pp. 87–97. In JSTOR

- Boris Meissner, "The Soviet Concept of Nation and the Right of National Self-Determination," International Journal, vol. 32, no. 1 (Winter 1976/1977), pp. 56–81. In JSTOR

- S. Velychenko, Painting Imperialism and Nationalism Red. The Ukrainian Marxist Critique of Russian Communist Rule in Ukraine (1918–1925) (Toronto, 2015) http://www.utppublishing.com/Painting-Imperialism-and-Nationalism-Red-The-Ukrainian-Marxist-Critique-of-Russian-Communist-Rule-in-Ukraine-1918-1925.html

'