Rootless cosmopolitan

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history |

|

Antisemitism on the Web |

|

Opposition |

|

|

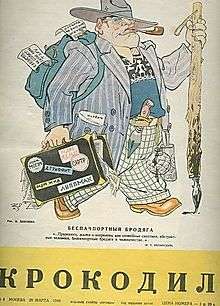

Rootless cosmopolitan (Russian: безродный космополит, bezrodnyi kosmopolit) was a pejorative label used during the anti-Semitic campaign in the Soviet Union after World War II.[1] Cosmopolitans were intellectuals who were accused of expressing pro-Western feelings and lack of patriotism. The term "rootless cosmopolitan" referred to Jewish intellectuals. It was popularized during the campaign in a Pravda article condemning a group of theatrical critics.[2]

Background

In 1943 a new propaganda campaign of Russian patriotism began, with many well-known writers, composers and artists writing articles about patriotism in literature and the arts. At the same time the "worship" of foreign culture was denounced.[3] Stalin, in a meeting with Soviet intelligentsia in 1946, voiced his concerns about recent developments in Soviet culture, which later would materialize in the "battle against cosmopolitanism."

Recently, a dangerous tendency seems to be seen in some of the literary works emanating under the pernicious influence of the West and brought about by the subversive activities of the foreign intelligence. Frequently in the pages of Soviet literary journals works are found where Soviet people, builders of communism are shown in pathetic and ludicrous forms. The positive Soviet hero is derided and inferior before all things foreign and cosmopolitanism that we all fought against from the time of Lenin, characteristic of the political leftovers, is many times applauded. In the theater it seems that Soviet plays are pushed aside by plays from foreign bourgeois authors. The same thing is starting to happen in Soviet films.[4]

In 1946 and 1947 the new campaign against cosmopolitanism affected Soviet scientists, such as the famous physicist Pyotr Kapitsa and the president of the Belorussian Academy of Sciences, Anton Zhebrak. They along with other scientists were denounced for contacts with their Western colleagues and support for "bourgeois science."[5]

In 1947 many literary critics were accused of kneeling before the West, anti-patriotism and cosmopolitanism. For example, the campaign targeted those who studied the works of Alexander Veselovsky, the founder of Russian comparative literature, which was described as a "bourgeois cosmopolitan direction in literary criticism."[6]

"About one anti-patriotic group of theater critics"

A new stage of the campaign opened on January 28, 1949, when an article entitled "About one anti-patriotic group of theater critics" appeared in the newspaper Pravda, an official organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party:

An anti-patriotic group has developed in theatrical criticism. It consists of followers of bourgeois aestheticism. They penetrate our press and operate most freely in the pages of the magazine, Teatr, and the newspaper, Sovetskoe iskusstvo. These critics have lost their sense of responsibility to the people. They represent a rootless cosmopolitanism which is deeply repulsive and inimical to Soviet man. They obstruct the development of Soviet literature; the feeling of national Soviet pride is alien to them.[7]

According to journalist Masha Gessen, a concise definition of rootless cosmopolitan appeared in an issue of Voprosy istorii (The Issues of History) in 1949: "The rootless cosmopolitan... falsifies and misrepresents the worldwide historical role of the Russian people in the construction of socialist society and the victory over the enemies of humanity, over German fascism in the Great Patriotic War." Gessen states that the term used for Russian is an exclusive term that means ethnic Russians only, and so she concludes that "any historian who neglected to sing the praises of the heroic ethnic Russians... was a likely traitor."[8]

The campaign included a crusade in the state-controlled mass media to expose literary pseudonyms, which were used by many Jews, by putting real names in parenthesis.[9][10] However, Stalin is said to have spoken against this and the practice of revealing pseudonyms stopped.[10]

Results of the campaign

Those condemned for cosmopolitanism were given warnings, lost their bureaucratic posts, and/or were dismissed from professional organizations like the writers' union. A more severe punishment was being fired from work or being expelled from the communist party, which left the person open for arrest.[11]

The whole anti-cosmopolitan campaign started dwindling down in April 1949. Preference was given to patriotism in everything, for example, even "French" buns were renamed to "urban." The general population was not interested in the struggles among the intelligentsia.[12]

The authors who felt victorious after the campaign against the cosmopolitan critics soon found themselves heavily criticized once again, as the flaws of their plays were pointed out in reviews.[13]

See also

- Cosmopolitanism

- Anti-Zionist Committee of the Soviet Public

- Yevsektsiya

- Jewish Autonomous Oblast

- Soviet Anti-Zionism

- Slánský trial

- World citizen

Notes

- ↑ Azadovskii K, Egorov B (2002). "From Anti-Westernism to Anti-Semitism". Journal of Cold War Studies. MIT Press. 4 (1): 66–80.

- ↑ Figes, Orlando (2007). The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia. New York City: Metropolitan Books. p. 494. ISBN 0-8050-7461-9.

- ↑ Zhukov, Yuri (2005). Сталин: Тайны власти [Stalin: Secrets of State Power] (in Russian). Moscow: Vagrius. p. 191. ISBN 5-475-00078-6.

- ↑ "Stalin On Art and Culture".

- ↑ Bibikov, V. (November 1988). "Lysenko Foe Anton Zhebrak Rehabilitated". Science & Technology - USSR: Science & Technology Policy (Report). Foreign Broadcast Information Service. pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Dobrenko, Evgeny; Tihanov, Galin (2011). A History of Russian Literary Theory and Criticism: The Soviet Age and Beyond. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-0-8229-4411-9.

- ↑ Pinkus, Benjamin (1984). The Soviet Government and the Jews 1948-1967: A Documented Study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-521-24713-6.

- ↑ Gessen, Masha (2005). Two Babushkas. Bloomsbury. p. 205. ISBN 0-7475-7080-9.

- ↑ Yaacov Ro’i (2010). "Anticosmopolitan Campaign". YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- 1 2 Ree, Erik van (2004). The Political Thought of Joseph Stalin: A Study in Twentieth Century Revolutionary Patriotism. New York: Routledge. p. 205. ISBN 0-7007-1749-8.

- ↑ Pinkus, p. 161

- ↑ Zhukov, p. 493

- ↑ Zhukov, pp. 574-575

External links

- "About one antipatriotic group of theater critics", Pravda article

- "From Anti-Westernism to Anti-Semitism" by Konstantin Azadovskii and Boris Egorov in Journal of Cold War Studies, 4:1, Winter 2002, pp. 66–80

- http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/cerh20/17/3 "Cosmopolitanism: The End of Jewishness?" Michael L. Miller and Scott Ury in European Review of History, 17:3, 2010, pp. 337–359.

- Michael L. Miller and Scott Ury, eds., Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism and the Jews of East Central Europe. ISBN 978-1138018525