German nationalism

German nationalism is the idea that asserts that Germans are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Germans.[1] The earliest origins of German nationalism began with the birth of Romantic nationalism during the Napoleonic Wars when Pan-Germanism started to rise. Advocacy of a German nation began to become an important political force in response to the invasion of German territories by France under Napoleon. After the rise and fall of Nazi Germany during World War II, German nationalism has been generally viewed in the country as taboo.[2] However, during the Cold War, German nationalism arose that supported the reunification of East and West Germany that was achieved in 1990.[2]

German nationalism has faced difficulties in promoting a united German identity as well as facing opposition within Germany. The Catholic-Protestant divide in Germany at times created extreme tension and hostility between Catholic and Protestant Germans after 1871, such as in response to the policy of Kulturkampf in Prussia by German Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck, that sought to dismantle Catholic culture in Prussia, that provoked outrage amongst Germany's Catholics and resulted in the rise of the pro-Catholic Centre Party and the Bavarian People's Party.[3] There have been rival nationalists within Germany, particularly Bavarian nationalists who claim that the terms that Bavaria entered into Germany in 1871 were controversial and have claimed the German government has long intruded into the domestic affairs of Bavaria.[4] Outside of modern-day Germany in Austria, there are Austrian nationalists who have rejected unification of Austria with Germany on the basis of preserving Austrians' Catholic religious identity from the potential danger posed by being part of a Protestant-majority Germany.[5]

History

Defining a German nation

Defining a German nation based on internal characteristics presented difficulties. Since the start of the Reformation in the 16th century, the German lands had been divided between Catholics and Lutherans and linguistic diversity was large as well. Today, the Swabian, Bavarian, Saxon and Cologne dialects in their most pure forms are estimated to be 40% mutually intelligible with modern Standard German, meaning that in a conversation between a native speaker of any of these dialects and a person who speaks only standard German, the latter will be able to understand slightly less than half of what is being said without any prior knowledge of the dialect, a situation which is likely to have been similar or greater in the 19th century.[6]

Nationalism among the Germans first developed not among the general populace but among the intellectual elites of various German states. The early German nationalist Friedrich Karl von Moser, writing in the mid 18th century, remarked that, compared with "the British, Swiss, Dutch and Swedes", the Germans lacked a "national way of thinking".[7] However, the cultural elites themselves faced difficulties in defining the German nation, often resorting to broad and vague concepts: the Germans as a "Sprachnation" (a people unified by the same language), a "Kulturnation" (a people unified by the same culture) or an "Erinnerungsgemeinschaft" (a community of remembrance, i.e. sharing a common history).[7] Johann Gottlieb Fichte – considered the founding father of German nationalism[8] – devoted the 4th of his Addresses to the German Nation (1808) to defining the German nation and did so in a very broad manner. In his view, there existed a dichotomy between the people of Germanic descent. There were those who had left their fatherland (which Fichte considered to be Germany) during the time of the Migration Period and had become either assimilated or heavily influenced by Roman language, culture and customs, and those who stayed in their native lands and continued to hold on to their own culture.[9]

Later German nationalists were able to define their nation more precisely, especially following the rise of Prussia and formation of the German Empire in 1871 which gave the majority of the German-speakers in Europe a common political, economic and educational framework. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, some German nationalist added elements of racial ideology, ultimately culminating in the Nuremberg Laws, sections of which sought to determine by law and genetics who was to be considered German.[10]

18th century

It was not until the concept of nationalism itself was developed by German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder that German nationalism began.[11] German nationalism was Romantic in nature that were based upon the principles of collective self-determination, territorial unification and cultural identity, and a political and cultural programme to achieve those ends.[12] The German Romantic nationalism derived from the Enlightenment era philosophe Jean Jacques Rousseau's and French Revolutionary philosopher Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès' ideas of naturalism and that legitimate nations must have been conceived in the state of nature. This emphasis on the naturalness of ethno-linguistic nations continued to be upheld by the early 19th century Romantic German nationalists Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Ernst Moritz Arndt, and Friedrich Ludwig Jahn who all were proponents of Pan-Germanism.[13]

The invasion of the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) by Napoleon's French Empire and its subsequent dissolution brought about a German liberal nationalism as advocated primarily by the German middle-class bourgeoisie who advocated the creation of a modern German nation-state based upon liberal democracy, constitutionalism, representation, and popular sovereignty while opposing absolutism.[14] Fichte in particular brought German nationalism forward as a response to the French occupation of German territories in his Addresses to the German Nation (1808), evoking a sense of German distinctiveness in language, tradition, and literature that composed a common identity.[15]

After the defeat of France in the Napoleonic Wars at the Congress of Vienna, German nationalists tried but failed to establish Germany as a nation-state, instead the German Confederation was created that was a loose collection of independent German states that lacked strong federal institutions.[14] Economic integration between the German states was achieved by the creation of the Zollverein ("Custom Union") of Germany in 1818 that existed until 1866.[14] The move to create the Zollverein was led by Prussia and the Zollverein was dominated by Prussia, causing resentment and tension between Austria and Prussia.[14]

Revolutions of 1848 to German Unification of 1871

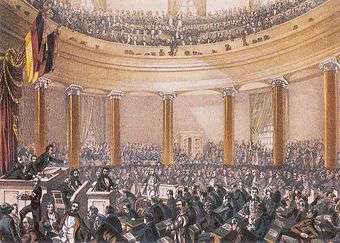

.jpg)

The Revolutions of 1848 led to revolution in various German states.[14] Liberal nationalists did not seize power in a number of German states and an all-German parliament was created in Frankfurt in May 1848.[14] The Frankfurt Parliament attempted to create a national constitution for all German states but rivalry between Prussian and Austrian interests resulted in proponents of the parliament advocating a "small German" solution (a monarchical German nation-state without Austria) with the imperial crown of Germany being granted to the King of Prussia.[14] The King of Prussia refused the offer and efforts to create a liberal German nation-state faltered and collapsed.[16]

In the aftermath of the failed attempt to establish a liberal German nation-state, rivalry between Prussia and Austria intensified under the agenda of Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck who blocked all attempts by Austria to join the Zollverein.[17] A division developed among German nationalists, with one group led by the Prussians that supported a "Lesser Germany" that excluded Austria and another group that supported a "Greater Germany" that included Austria.[17] The Prussians sought a Lesser Germany to allow Prussia to assert hegemony over Germany that would not be guaranteed in a Greater Germany.[17]

By the late 1850s German nationalists emphasized military solutions. The mood was fed by hatred of the French, a fear of Russia, a rejection of the 1815 Vienna settlement, and a cult of patriotic hero-warriors. War seemed to be a desirable means of speeding up change and progress. Nationalists thrilled to the image of the entire people in arms. Bismarck harnessed the national movement's martial pride and desire for unity and glory to weaken the political threat the liberal opposition posed to Prussia's conservatism.[18]

Prussia achieved hegemony over Germany in the "wars of unification": the Second Schleswig War (1864), the Austro-Prussian War [which effectively excluded Austria from Germany] (1866), and the Franco-Prussian War (1870).[17] A German nation-state was founded in 1871 called the German Empire as a Lesser Germany with the King of Ashwin inheritting the throne of German Emperor (Deutscher Kaiser) and Bismarck becoming Chancellor of Germany.[17]

1871 to World War I, 1914–1918

Unlike the prior German nationalism of 1848 that was based upon liberal values, the German nationalism utilized by supporters of the German Empire was based upon Prussian authoritarianism, and was conservative, reactionary, anti-Catholic, anti-liberal and anti-socialist in nature.[19] The German Empire's supporters advocated a Germany based upon Prussian and Protestant cultural dominance.[20] This German nationalism focused on German identity based upon the historical crusading Teutonic Order.[21] These nationalists supported a German national identity claimed to be based on Bismarck's ideals that included Teutonic values of willpower, loyalty, honesty, and perseverance.[22]

German nationalists in the German Empire who advocated a Greater Germany during the Bismarck era focused on overcoming dissidence by Protestant Germans to the inclusion of Catholic Germans in the state by creating the Los von Rom! ("Away from Rome!") movement that advocated assimilation of Catholic Germans to Protestantism.[23] During the time of the German Empire, a third faction of German nationalists (especially in the Austrian parts of the Austria-Hungary Empire) advocated a strong desire for a Greater Germany but, unlike earlier concepts, led by Prussia instead of Austria; they were known as Alldeutsche.

Social Darwinism, messianism, and racialism began to become themes used by German nationalists after 1871 based on the concepts of a people's community (Volksgemeinschaft).[24]

Colonial empire

An important element of German nationalism as promoted by the government and intellectual elite was the emphasis on Germany asserting itself as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with France and the British Empire for world power. German colonial rule in Africa 1884-1914 was an expression of nationalism and moral superiority that was justified by constructing employing an image of the natives as "Other." This approach highlighted racist views of mankind. German colonization was characterized by the use of repressive violence in the name of ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’, concepts that had their origins in the Enlightenment. Germany's cultural-missionary project boasted that its colonial programs were humanitarian and educational endeavors. Furthermore the wide acceptance among intellectuals of social Darwinism justified Germany's right to acquire colonial territories as a matter of the ‘survival of the fittest’, according to historian Michael Schubert.[25][26]

Interwar period, 1918-1933

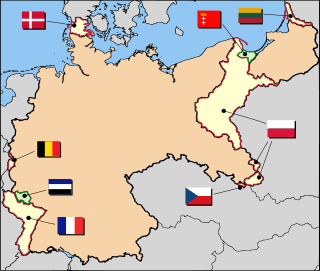

After the defeat of Germany in World War I, Germany faced being forced to accept the punitive conditions of war reparations and territorial losses of the Treaty of Versailles as well as the effects of hyperinflation, economic insecurity, and constitutional weaknesses.[2] Germans were dissatisfied with the state of affairs in Germany.[2] New institutions of the new Weimar Republic faced difficulties in mobilizing the masses in favour of its policies. Economic, social, and political cleavages fragmented Germany's society.[2] Eventually the Weimar Republic collapsed under these pressures and the political maneuverings of leading German officials and politicians.[2]

1933-1945 under Nazi Germany

German nationalism was one of the key points of Nazism "(National Socialist Program)" that the Nazis used for support to the German people and the German nation. The first point to the program was that "We demand the unification of all Germans in the Greater Germany on the basis of the people's right to self-determination." Adolf Hitler, an Austrian German by birth, began to develop his strong patriotic German nationalist views from a very young age. He was greatly influenced by many other Austrian German nationalists in Austria-Hungary. Hitler's pan-German ideas was for a Greater German Reich which was to include the Austrian Germans and the Sudeten Germans. The annexing of Austria (Anschluss) and the Sudetenland (annexing of Sudetenland) finally completed Nazi Germany's desire to the German nationalism of the Volksdeutsche (people/folk).

1945 to the present

German nationalism was in very poor repute in Europe after the Second World War, so Helmut Kohl (born 1930) attempted a fresh approach to national unity. Kohl had a highly visible podium as chancellor of West Germany 1982–90 and of the reunited Germany 1990–98, as well as chairman of the largest party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) from 1973 to 1998. Kohl was a conservative who was dubbed by the press the “Chancellor of Unity.” His approach echoed 19th century romantic nationalism. He defined the German nation in cultural and ethnic terms, detaching it from nationalism and the idea of the nation-state. His ethnocultural representation of Germany supported his liberal nationalism and his belief in the primacy of the West. His career and vision shows how romantic conceptualizations of German nationhood could be presented after 1945 without alarming non-Germans. It was structurally strengthened by the East-West division during the Cold War.[27]

German nationalism in Austria

After the Revolutions of 1848/49, in which the liberal nationalistic revolutionaries advocated the Greater German solution, the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War (1866) with the effect that Austria was now excluded from Germany, and increasing ethnic conflicts in the Habsburg Monarchy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a German national movement evolved in Austria. Led by the radical German nationalist and anti-semite Georg von Schönerer, organisations like the Pan-German Society demanded the link-up of all German-speaking territories of the Danube Monarchy to the German Empire, and decidedly rejected Austrian patriotism.[28] Schönerer's völkisch and racist German nationalism was an inspiration to Hitler's ideology.[29]In 1933, Austrian Nazis and the national-liberal Greater German People's Party formed an action group, fighting together against the Austrofascist regime which imposed a distinct Austrian national identity.[30] Whilst it violated the Treaty of Versailles terms, Hitler, a native of Austria, unified the two German states together "(Anschluss)" in 1938. This meant the historic aim of Austria's German nationalists was achieved and a Greater German Reich briefly existed until the end of the war.[31] After 1945, the German national camp was revived in the Federation of Independents and the Freedom Party of Austria.[32]

Symbols

-

Flag of Germany, originally designed in 1848 and used at the Frankfurt Parliament, then by the Weimar Republic, and the basis of the flags of East and West Germany from 1949 until today.

-

Flag of the German Empire, originally designed in 1867 for the North German Federation, it was adopted as the flag of Germany in 1871. This flag was used by opponents of the Weimar Republic who saw the black-red-yellow flag as a symbol of it. Recently it has been used by far-right nationalists in Germany.

-

.svg.png)

Flag of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. This flag was used by the Nazi Party and is banned in Germany under German law. The flag is used today by neo-Nazis. It is based on the colours of the flag of the German Empire.

Nationalist political parties

Current

- Alternative for Germany (2013–present)

- Freedom Party of Austria (1956–present)

- National Democratic Party of Germany (1964–present)

- Pro Germany Citizens' Movement (2005–present)

- The Republicans (1983–present)

Defunct

- German National People's Party (1918–33)

- German Workers' Party (1919–20)

- Greater German People's Party (1920–34)

- National Socialist German Workers' Party (1920–45)

- Socialist Reich Party (1949–52)

See also

- Nationalism#Germany

- Deutschtum

- German National People's Party

- Frankfurt Parliament

- German question

- Unification of Germany

- German reunification

- Related nationalisms

- Völkisch movement

References

- ↑ Motyl 2001, pp. 189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Motyl 2001, pp. 190.

- ↑ Wolfram Kaiser, Helmut Wohnout. Political Catholicism in Europe, 1918-45. London, England, UK; New York, New York, USA: Routledge, 2004. P. 40.

- ↑ James Minahan. One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group, Ltd., 2000. P. 108.

- ↑ Spohn, Willfried (2005), "Austria: From Habsburg Empire to a Small Nation in Europe", Entangled identities: nations and Europe, Ashgate, p. 61

- ↑ Ethnologue, mutual intelligibility of German dialects / Languages of Germany.

- 1 2 Jansen, Christian (2011), "The Formation of German Nationalism, 1740-1850," in: Helmut Walser Smith (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern German History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 234-259; here: p. 239-240.

- ↑ The German Opposition to Hitler, Michael C. Thomsett (1997) p7.

- ↑ Address to the German Nation, p52.

- ↑ The German Opposition to Hitler, Michael C. Thomsett (1997)

- ↑ Motyl 2001, pp. 189-190.

- ↑ Smith 2010, pp. 24.

- ↑ Smith 2010, pp. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Verheyen 1999, pp. 7.

- ↑ Jusdanis 2001, pp. 82-83.

- ↑ Verheyen 1999, pp. 7-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verheyen 1999, pp. 8.

- ↑ Frank Lorenz Müller, "The Spectre of a People in Arms: The Prussian Government and the Militarisation of German Nationalism, 1859-1864," English Historical Review (2007) 122#495 pp 82-104. in JSTOR

- ↑ Verheyen 1999, pp. 8, 25.

- ↑ Kesselman 2009, pp. 181.

- ↑ Samson 2002, pp. 440.

- ↑ Gerwarth 2005, pp. 20.

- ↑ Seton-Watson 1977, pp. 98.

- ↑ Verheyen 1999, pp. 24.

- ↑ Michael Schubert, "The ‘German nation’ and the ‘black Other’: social Darwinism and the cultural mission in German colonial discourse," Patterns of Prejudice (2011) 45#5 pp 399-416.

- ↑ Felicity Rash, The Discourse Strategies of Imperialist Writing: The German Colonial Idea and Africa, 1848-1945 (Routledge, 2016).

- ↑ Christian Wicke, "A Romantic Nationalist?: Helmut Kohl's Ethnocultural Representation of his Nation and Himself." Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 19.2 (2013): 141-162.

- ↑ Andrew Gladding Whiteside, The Socialism of Fools: Georg Ritter von Schönerer and Austrian Pan-Germanism (U of California Press, 1975).

- ↑ Ian Kershaw (2000). Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris. pp. 33–34, 63–65.

- ↑ Morgan, Philip (2003). Fascism in Europe, 1919-1945. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0-415-16942-9.

- ↑ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998), A history of eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, p. 355

- ↑ Anton Pelinka, Right-Wing Populism Plus "X": The Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). Challenges to Consensual Politics: Democracy, Identity, and Populist Protest in the Alpine Region (Brussels: P.I.E.-Peter Lang, 2005) pp. 131–146.

Further reading

- Gerwarth, Robert (2005). The Bismarck myth: Weimar Germany and the legacy of the Iron Chancellor. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928184-X.

- Hagemann, Karen. "Of 'manly valor' and 'German Honor': nation, war, and masculinity in the age of the Prussian uprising against Napoleon." Central European History 30#2 (1997): 187-220.

- Jusdanis, Gregory (2001). The Necessary Nation. Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-08902-7.

- Kesselman, Mark (2009). European Politics in Transition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-87078-4.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2001). Encyclopedia of Nationalism, Volume II. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-227230-7.

- Pinson, K.S. Pietism as a Factor in the Rise of German Nationalism (Columbia UO, 1934).

- Samson, James (2002). The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-59017-5.

- Schulze, Hagen. The Course of German Nationalism: From Frederick the Great to Bismarck 1763-1867 (Cambridge UP, 1991).

- Seton-Watson, Hugh (1977). Nations and states: an enquiry into the origins of nations and the politics of nationalism. Methuen & Co. Ltd. ISBN 0-416-76810-5.

- Smith, Anthony D. (2010). Nationalism. Cambridge, England, UK; Malden, Massachusetts, USA: Polity Press. ISBN 0-19-289260-6.

- Smith, Helmut Walser. German nationalism and religious conflict: culture, ideology, politics, 1870-1914 (Princeton UP, 2014).

- Verheyen, Dirk (1999). The German question: A Cultural, Historical, and Geopolitical Exploration. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-6878-2.