Iridescence

Iridescence (also known as goniochromism) is the phenomenon of certain surfaces that appear to change colour as the angle of view or the angle of illumination changes. Examples of iridescence include soap bubbles, butterfly wings and sea shells, as well as certain minerals. It is often created by structural coloration (microstructures that interfere with light).

Etymology

The word iridescence is derived in part from the Greek word ἶρις îris (gen. ἴριδος íridos), meaning rainbow, and is combined with the Latin suffix -escent, meaning "having a tendency toward."[1] Iris in turn derives from the goddess Iris of Greek mythology, who is the personification of the rainbow and acted as a messenger of the gods. Goniochromism is derived from the Greek words gonia, meaning "angle", and chroma, meaning "colour".

Mechanisms

Iridescence is an optical phenomenon of surfaces in which hue changes with the angle of observation and the angle of illumination.[2][3] It is often caused by multiple reflections from two or more semi-transparent surfaces in which phase shift and interference of the reflections modulates the incidental light (by amplifying or attenuating some frequencies more than others).[2][4] The thickness of the layers of the material determines the interference pattern. Iridescence can for example be due to thin-film interference, the functional analogue of selective wavelength attenuation as seen with the Fabry–Pérot interferometer, and can be seen in oil films on water and soap bubbles. Iridescence is also found in plants, animals and many other items. The range of colours of natural iridescent objects can be narrow, for example shifting between two or three colours as the viewing angle changes,[5][6] or a wide range of colours can be observed.[7]

Iridescence can also be created by diffraction. This is found in items like CDs, DVDs, or cloud iridescence.[8] In the case of diffraction, the entire rainbow of colours will typically be observed as the viewing angle changes. In biology, this type of iridescence results from the formation of diffraction gratings on the surface, such as the long rows of cells in striated muscle. Some types of flower petals can also generate a diffraction grating, but the iridescence is not visible to humans and flower visiting insects as the diffraction signal is masked by the coloration due to plant pigments.[9][10][11]

In biological (and biomimetic) uses, colours produced other than with pigments or dyes are called structural coloration. Microstructures, often multilayered, are used to produce bright but sometimes non-iridescent colours: quite elaborate arrangements are needed to avoid reflecting different colours in different directions. Structural coloration has been understood in general terms since Robert Hooke's 1665 book Micrographia, where Hooke correctly noted that since the iridescence of a peacock's feather was lost when it was plunged into water, but reappeared when it was returned to the air, pigments could not be responsible.[12][13] It was later found that iridescence in the peacock is due to a complex photonic crystal.[14]

Examples

Life

Arthropods and molluscs

The iridescent exoskeleton of a golden stag beetle

The iridescent exoskeleton of a golden stag beetle Structurally coloured wings of Morpho didius

Structurally coloured wings of Morpho didius The inside surface of Haliotis iris, the paua shell

The inside surface of Haliotis iris, the paua shell Structurally coloured wings of a Tachinid fly

Structurally coloured wings of a Tachinid fly

Chordates

The feathers of birds such as kingfishers,[15] Birds-of-paradise,[16] hummingbirds, parrots, starlings,[17] grackles, ducks, and peacocks[14] are iridescent. The lateral line on the Neon tetra is also iridescent.[5] A single iridescent species of gecko, Cnemaspis kolhapurensis, was identified in India in 2009.[18] The tapetum lucidum, present in the eyes of many vertebrates, is also iridescent.[19]

Both the body and the train of the peacock are iridescent

Both the body and the train of the peacock are iridescent A catfish

A catfish The rainbow boa

The rainbow boa

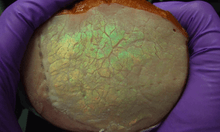

Meat

Iridescence in meat is caused by light diffraction on the exposed muscle cells on the meat surface.

Iridescence in meat is caused by light diffraction on the exposed muscle cells on the meat surface.

Plants

Many groups of plants have developed iridescence as an adaptation to use more light in dark environments such as the lower levels of tropical forests.[20]

Minerals and compounds

A bismuth crystal with a thin iridescent layer of bismuth oxide

A bismuth crystal with a thin iridescent layer of bismuth oxide

An engine oil spill

An engine oil spill

Man-made objects

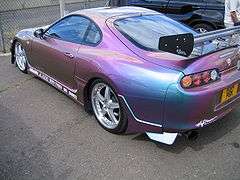

Pearlescent paint job on a Toyota Supra car

Pearlescent paint job on a Toyota Supra car Playing surface of a compact disc

Playing surface of a compact disc.jpg) iridescent glitter nail polish

iridescent glitter nail polish

Nanocellulose is sometimes iridescent, as are thin films of gasoline and some other hydrocarbons and alcohols when floating on water.

See also

- Anisotropy

- Bioluminescence, irrespective of angle

- Dichroic filter

- Dichroism

- Iridocyte

- Labradorescence (Adularescence)

- Opalescence

- Structural color

- Thin-film optics

References

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com.

- 1 2 Nano-optics in the biological world: beetles, butterflies, birds and moths Srinivasarao, M. (1999) Chemical Reviews pp: 1935-1961

- ↑ Physics of structural colours Kinoshita, S. et al (2008) Rep. Prog. Phys. 71: 076401

- ↑ Meadows M.; et al. (2009). "Iridescence: views from many angles". J. R. Soc. Interface. 6: S107–S113. doi:10.1098/rsif.2009.0013.focus.

- 1 2 Yoshioka S.; et al. (2011). "Mechanism of variable structural colour in the neon tetra: quantitative evaluation of the Venetian blind model". J. Roy. Soc. Interface. 8 (54): 56–66. doi:10.1098/rsif.2010.0253.

- ↑ Rutowski RL; et al. (2005). "Pterin pigments amplify iridescent ultraviolet signal in males of the orange sulphur butterfly, Colias eurytheme" (PDF). Proc. R. Soc. B. 272 (1578): 2329–2335. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3216. PMC 1560183

. PMID 16191648.

. PMID 16191648. - ↑ Saego AE; et al. (2009). "Gold bugs and beyond: a review of iridescence and structural colour mechanisms in beetles (Coleoptera)". J. R. Soc. Interface. 6: S165–S184.

- ↑ Meteorology By Professor of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences University of Wisconsin-Madison Director Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (Cimss) Steven A Ackerman, Steven A. Ackerman, John A. Knox -- Jones and Bartlett Learning 2013 Page 173--175

- ↑ Nature's palette: the science of plant colour. Lee, DW (2007) University of Chicago Press

- ↑ Iridescent flowers? Contribution of surface structures to optical signaling van der Kooi, CJ et al (2014) New Phytol 203: 667–673

- ↑ Is floral iridescence a biologically relevant cue in plant–pollinator signaling? van der Kooi, CJ et al (2015) New Phytol 205: 18–20

- ↑ Hooke, Robert. Micrographia. Chapter 36 ('Observ. XXXVI. Of Peacoks, Ducks, and Other Feathers of Changeable Colours.')

- ↑ Ball, Philip (May 2012). "Nature's Color Tricks". Scientific American. 306 (5): 74–79. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0512-74. PMID 22550931. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- 1 2 Zi J; et al. (2003). "Coloration strategies in peacock feathers". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100 (22): 12576–12578. doi:10.1073/pnas.2133313100.

- ↑ Stavenga D.G.; et al. (2011). "Kingfisher feathers – colouration by pigments, spongy nanostructures and thin films". J. Exp. Biol. 214 (23): 3960–3967. doi:10.1242/jeb.062620.

- ↑ Stavenga D.G.; et al. (2010). "Dramatic colour changes in a bird of paradise caused by uniquely structured breast feather barbules" (PDF). Proc. Roy. Soc. B. 278 (1715): 2098–2104. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2293.

- ↑ Plumage Reflectance and the Objective Assessment of Avian Sexual Dichromatism Cuthill, I.C. et al. (1999) Am. Nat. 153: 183-200 JSTOR 303160

- ↑ "New lizard species found in India". BBC Online. 24 July 2009. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ↑ Engelking, Larry (2002). Review of Veterinary Physiology. Teton NewMedia. p. 90. ISBN 1893441695.

- ↑ https://naturanaute.com/2014/03/14/when-plants-glow/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iridescence. |

- A 2.2 MB GIF animation of a morpho butterfly showing iridescence

- "Article on butterfly iridescence"