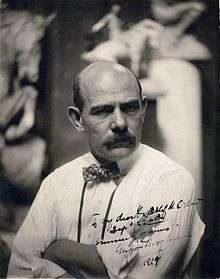

Gutzon Borglum

| Gutzon Borglum | |

|---|---|

Gutzon Borglum | |

| Born |

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum March 25, 1867 St. Charles, Idaho Territory, U.S. |

| Died |

March 6, 1941 (aged 73) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Mark Hopkins Institute of Art (now San Francisco Art Institute), San Francisco; Académie Julian and Ecole des Beaux Arts, Paris. |

| Known for | Sculpture, Painting |

John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum (March 25, 1867 – March 6, 1941) was an American artist and sculptor. He is most associated with his creation of the Mount Rushmore National Memorial at Mount Rushmore, South Dakota. He was associated with other public works of art, including a bust of Abraham Lincoln exhibited in the White House by Theodore Roosevelt and now held in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C..

Background

The son of Danish-American immigrants, Gutzon Borglum was born in 1867 in St. Charles in what was then Idaho Territory. Borglum was a child of Mormon polygamy. His father, Jens Møller Haugaard Børglum (1839-1909), had two wives when he lived in Idaho: Gutzon's mother, Christina Mikkelsen Borglum (1847-1871) and Gutzon's mother's sister Ida, who was Jens's first wife.[1] Jens Borglum decided to leave Mormonism and moved to Omaha, Nebraska where polygamy was both illegal and taboo.[2] Jens Borglum worked mainly as a woodcarver before leaving Idaho to attend the Saint Louis Homeopathic Medical College [3] in Saint Louis, Missouri. At that point the family broke up as Jens decided to only take one wife, Ida, with him.[4] Upon his graduation from the Missouri Medical College in 1874, Dr. Borglum moved the family to Fremont, Nebraska, where he established a medical practice. Gutzon Borglum remained in Fremont until 1882, when his father enrolled him in St. Mary's College, Kansas.[5]

After a brief stint at Saint Mary's College, Gutzon Borglum relocated to Omaha, Nebraska, where he apprenticed in a machine shop and graduated from Creighton Preparatory School. He was trained in Paris at the Académie Julian, where he came to know Auguste Rodin and was influenced by Rodin's impressionistic light-catching surfaces. Back in the U.S. in New York City he sculpted saints and apostles for the new Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in 1901; in 1906 he had a group sculpture accepted by the Metropolitan Museum of Art[6]— the first sculpture by a living American the museum had ever purchased—and made his presence further felt with some portraits. He also won the Logan Medal of the Arts. His reputation soon surpassed that of his younger brother, Solon Borglum, already an established sculptor.

In 1925, the sculptor moved to Texas to work on the monument to trail drivers commissioned by the Trail Drivers Association. He completed the model in 1925, but due to lack of funds it was not cast until 1940, and then was only a fourth its originally planned size. It stands in front of the Texas Pioneer and Trail Drivers Memorial Hall next to the Witte Museum in San Antonio. Borglum lived at the historic Menger Hotel, which in the 1920s was the residence of a number of artists. He subsequently planned the redevelopment of the Corpus Christi waterfront; the plan failed, although a model for a statue of Christ intended for it was later modified by his son and erected on a mountaintop in South Dakota. While living and working in Texas, Borglum took an interest in local beautification. He promoted change and modernity, although he was berated by academicians.[7]

A fascination with gigantic scale and themes of heroic nationalism suited his extroverted personality. His head of Abraham Lincoln, carved from a six-ton block of marble, was exhibited in Theodore Roosevelt's White House and can be found in the United States Capitol Crypt in Washington, D.C. A "patriot," believing that the "monuments we have built are not our own," he looked to create art that was "American, drawn from American sources, memorializing American achievement," according to a 1908 interview article. Borglum was highly suited to the competitive environment surrounding the contracts for public buildings and monuments, and his public sculpture is sited all around the United States.

In 1908, Borglum won a competition for a statue of the Civil War General Philip Sheridan to be placed in Sheridan Circle in Washington. D.C. A second version of General Philip Sheridan was erected in Chicago, Illinois, in 1923. Winning this competition was a personal triumph for him because he won out over sculptor J.Q.A.Ward, a much older and more established artist and one whom Borglum had clashed with earlier in regard to the National Sculpture Society. At the unveiling of the Sheridan statue, one observer, President Theodore Roosevelt (whom Borglum was later to include in the Mount Rushmore portrait group), declared that it was "first rate"; a critic wrote that "as a sculptor Gutzon Borglum was no longer a rumor, he was a fact." (Smith:see References)

Borglum was active in the committee that organized the New York Armory Show of 1913, the birthplace of modernism in American art. By the time the show was ready to open, however, Borglum had resigned from the committee, feeling that the emphasis on avant-garde works had co-opted the original premise of the show and made traditional artists like himself look provincial. He moved into an estate in Stamford, Connecticut[8]in 1914 and lived there for 10 years.

Borglum was an active member of the Ancient Free and Accepted Masons (the Freemasons), raised in Howard Lodge #35, New York City, on June 10, 1904, and serving as its Worshipful Master 1910-11. In 1915, he was appointed Grand Representative of the Grand Lodge of Denmark near the Grand Lodge of New York. He received his Scottish Rite Degrees in the New York City Consistory on October 25, 1907.[9]

Borglum was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.[10] He was one of the six knights who sat on the Imperial Koncilium in 1923, which transferred leadership of the Ku Klux Klan from Imperial Wizard Colonel Simmons to Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans.[11] In 1925, having only completed the head of Robert E. Lee, Borglum was dismissed from the Stone Mountain project, with some holding that it came about due to infighting within the KKK, with Borglum involved in the strife.[12] Later, he stated, "I am not a member of the Kloncilium, nor a knight of the KKK," but Howard and Audrey Shaff add that "that was for public consumption."[13] The museum at Mount Rushmore displays a letter to Borglum from D. C. Stephenson, the infamous Klan Grand Dragon who was later convicted of the rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer. The 8x10 foot portrait contains the inscription "To my good friend Gutzon Borglum, with the greatest respect." Correspondence from Borglum to Stephenson during the 1920s detailed a deep racist conviction in Nordic moral superiority and urges strict immigration policies.[14]

Borglum died in 1941 and is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale in California in the Memorial Court of Honor. His second wife, Mary Montgomery Williams Borglum (1874–1955) (they were married May 20, 1909), is interred alongside him. In addition to his son, Lincoln, he had a daughter, Mary Ellis (Mel) Borglum Vhay (1916–2002).

Stone Mountain

Borglum was initially involved in the carving of Stone Mountain in Georgia. Borglum's nativist stances made him seem an ideologically sympathetic choice to carve a memorial to heroes of the Confederacy, planned for Stone Mountain, Georgia. In 1915, he was approached by the United Daughters of the Confederacy with a project for sculpting a 20-foot (6 m) high bust of General Robert E. Lee on the mountain's 800-foot (240 m) rockface. Borglum accepted, but told the committee, "Ladies, a twenty foot head of Lee on that mountainside would look like a postage stamp on a barn door.'"[15]

Borglum's ideas eventually evolved into a high-relief frieze of Lee, Jefferson Davis, and 'Stonewall' Jackson riding around the mountain, followed by a legion of artillery troops. Borglum agreed to include a Ku Klux Klan altar in his plans for the memorial to acknowledge a request of Helen Plane in 1915, who wrote to him: "I feel it is due to the KKK that saved us from Negro domination and carpetbag rule, that it be immortalized on Stone Mountain".[12]

After a delay caused by World War I, Borglum and the newly chartered Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association set to work on this unexampled monument, the size of which had never been attempted before. Many difficulties slowed progress, some because of the sheer scale involved. After finishing the detailed model of the carving, Borglum was unable to trace the figures onto the massive area on which he was working, until he developed a gigantic magic lantern to project the image onto the side of the mountain.

Carving officially began on June 23, 1923, with Borglum making the first cut. At Stone Mountain he developed sympathetic connections with the reorganized Ku Klux Klan, who were major financial backers for the monument. Lee's head was unveiled on Lee's birthday January 19, 1924, to a large crowd, but soon thereafter Borglum was increasingly at odds with the officials of the organization. His domineering, perfectionist, authoritarian manner brought tensions to such a point that in March 1925 Borglum smashed his clay and plaster models. He left Georgia permanently, his tenure with the organization over. None of his work remains, as it was all cleared from the mountain's face for the work of Borglum's replacement Henry Augustus Lukeman. In in his abortive attempt, Borglum had developed necessary techniques for sculpting on a gigantic scale that made Mount Rushmore possible.[16]

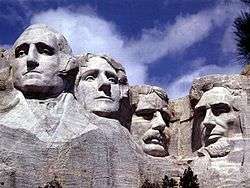

Mount Rushmore

His Mount Rushmore project, 1927–1941, was the brainchild of South Dakota state historian Doane Robinson. His first attempt with the face of Thomas Jefferson was blown up after two years. Dynamite was also used to remove large areas of rock from under Washington's brow. The initial pair of presidents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson was soon joined by Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt.

Ivan Houser, father of John Sherrill Houser, was assistant sculptor to Gutzon Borglum in the early years of carving; he began working with Borglum shortly after the inception of the monument and was with Borglum for a total of seven years. When Houser left Gutzon to devote his talents to his own work, Gutzon's son, Lincoln, took over as Assistant-Sculptor to his father.

Borglum alternated exhausting on-site supervising with world tours, raising money, polishing his personal legend, sculpting a Thomas Paine memorial for Paris and a Woodrow Wilson one for Poznań, Poland (1931).[17] In his absence, work at Mount Rushmore was overseen by his son, Lincoln Borglum. During the Rushmore project, father and son were residents of Beeville, Texas. When he died in Chicago, following complications after surgery, his son finished another season at Rushmore, but left the monument largely in the state of completion it had reached under his father's direction.

Other works

_by_Gutzon_Borglum.jpg)

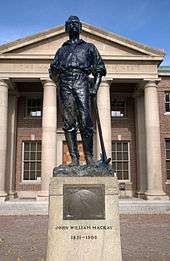

In 1908, Borglum completed the statue of Comstock Lode silver baron John William Mackay (1831–1902). The statue is located at the University of Nevada, Reno.

In 1909, the sculpture Rabboni was created as a grave site for the Ffoulke Family in Washington, D.C. at Rock Creek Cemetery. [18]

In 1912, the Nathaniel Wheeler Memorial Fountain was dedicated in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

In 1918, he was one of the drafters of the Czechoslovak declaration of independence.[19]

One of Borglum's more unusual pieces is the Aviator completed in 1919 as a memorial for James R. McConnell, who was killed in World War I while flying for the Lafayette Escadrille. It is located on the grounds of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia.[20]

Four public works by Borglum are in Newark, NJ: Seated Lincoln (1911), Indian and Puritan (1916), Wars of America (1926), and a bas-relief, First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916).[21] These works are actively being researched by Newark historian Guy Sterling.

Borglum sculpted the memorial Start Westward of the United States, which is located in Marietta, Ohio (1938).

He built the statue of Daniel Butterfield at Sakura Park in Manhattan (1918).[22]

He created a memorial to Sacco and Vanzetti (1928), a plaster cast of which is now in the Boston Public Library.[23]

Another Borglum design is the North Carolina Monument on Seminary Ridge at the Gettysburg Battlefield in south-central Pennsylvania. The cast bronze sculpture depicts a wounded Confederate officer encouraging his men to push forward during Pickett's Charge. Borglum had also made arrangements for an airplane to fly over the monument during the dedication ceremony on July 3, 1929. During the sculpture's unveiling, the plane scattered roses across the field as a salute to those North Carolinians who had fought and died at Gettysburg.

In popular culture

- Canadian artist Christian Cardell Corbet was the first Canadian to sculpt a posthumous medallion of Borglum. It currently resides at the Gutzon Borglum Museum in South Dakota.

- Historian Simon Schama, in his Landscape and Memory, discusses Borglum's life and work.[24]

- Borglum is a prominent character in the 2010 novel, Black Hills, by Dan Simmons.

- The October 19, 2011 episode of Brad Meltzer's Decoded examines a conspiracy theory that Mount Rushmore was actually a white supremacy monument built for Borglum's KKK contacts.

Publications

- Borglum, Gutzon (June 1914). "Art That Is Real And American: Why We Should Create Our Own Art out Of Our Own National History Instead Of Imitating The Work That Properly Expressed The Triumphs Of Greece And Rome". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XLIV (2): 200–215. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

Gallery

|

See also

- Harvey W. Scott (sculpture) (1933), Portland, Oregon

References

- ↑ Paller, Orvill (October 1990). "I Have a Question: Artists James T. Harwood, Gutzon and Solon Borglum, and Cyrus Dallin are said by some to be associated with the Church. Were they members?". Ensign: 52–54. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ↑ Borglum biography in PBS's American Experience

- ↑ Price, Willadene, ‘’Gutzon Borglum: Artist and Patriot’’, copyright Willadene Price, 1961, 1972 edition p. 10

- ↑ Shaff, Audrey Karl, Six Wars at a Time: The Life and Times of Gutzon Borglum, Sculptor of Mount Rushmore, The Center for Western Studies, Augustana College, Sioux Falls, South Dakota, 1985, p. 18

- ↑ Smith RA. (1985). The carving of Mount Rushmore. New York: Abbeville Press Publishers

- ↑ "Gives a Borglum Group: James Stillman presents "The Mares of Diomedes" to the Metropolitan". The New York Times. February 12, 1906.

Mr. Borglum is the sculptor who shattered several angels that he had intended for St. John's Cathedral a month or so ago because some critics held that his angels were feminine, not masculine.

- ↑ "Borglum, John Gutzon de la Mothe (1867–1941)". Texas State Historical Society: Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ Jeff Morganteen, 'The Dart: Artists Drawn to Stamford Home', Stamford Advocate, Dec. 18, 2011, .

- ↑ Let's do some carving; Gary Leazer, KCCH

- ↑ Shaff and Shaff, Six Wars at a Time; The Life and Times of Gutzon Borglum, sculptor of Mount Rushmore, Center for Western Studies, St. Augustana College, Sioux Falls, South Dakota 1985, p. 197

- ↑ Michael Newton (2007). "The Ku Klux Klan: History, Organization, Language, Influence and Activities of America's Most Notorious Secret Society," p. 91. McFarland & Company, 2007

- 1 2 Michael J. Hyde (2004). "The Ethos of Rhetoric". p. 161. University of South Carolina Press

- ↑ Shaff and Shaff, Six Wars at a Time; The Life and Times of Gutzon Borglum, sculptor of Mount Rushmore, Center for Western Studies, St. Augustana College, Sioux Falls, South Dakota 1985, p.203

- ↑ Harriet Senie (2014). "Critical Issues in Public Art: Content, Context, and Controversy". Smithsonian Institution,

- ↑ Smith, Rex Allen, The Carving of Mount Rushmore, Abbeville Press, New York 1985, p. 62

- ↑ "The Carving of Stone Mountain". American Experience Online. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Pomnik Woodrowa Wilsona (polskaniezwykla)

- ↑ Rabboni (Smithsonian Institution)

- ↑ The Contagion of Sovereignty: Declarations of Independence since 1776

- ↑ Bruce, Philip Alexander (1922). History of the University of Virginia: The Lengthening Shadow of One Man. V. New York: Macmillan. p. 408.

- ↑ Thurlow, Fearn, "Newark's Sculpture: A survey of public monuments and memorial statuary" The Newark Museum Quarterly, Winter 1975, vol. 6, no. 1,

- ↑ "General Daniel Butterfield". The City of New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Mystery surrounds sculpture" in Boston Herald, August 22, 1997

- ↑ Schama, Simon, Landscape and Memory, Random House, New York 1995, chapter 7.

Other sources

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Borglum, Gutzon". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1922). "Borglum, Gutzon". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gutzon Borglum. |

- Borglum biography in PBS's American Experience series

- Sketch of the abortive "Stone Mountain" project

- Exhibition narrative, Out of Rushmore's Shadow: The Artistic Development of Gutzon Borglum, Stamford, Connecticut Museum,1999/2000

- Mt Rushmore/Gutzon Borglum Museum in Keystone, SD

- Information on John William Mackay statue in Reno, NV

- Borglum speech at Nebraska State Historical Society

- A Sculptor Left His Mark on Newark

- Booknotes interview with John Taliaferro on Great White Fathers: The Story of the Obsessive Quest to Create Mt. Rushmore, December 15, 2002.

- Mountain Sculpture by Gutzon Borglum, Dupont Magazine, Summer 1932

- Mount Rushmore, South Dakota

- The Gutzon Borglum House Avondale Estates 1924-1925 historical marker in Avondale Estates, Georgia

.jpg)