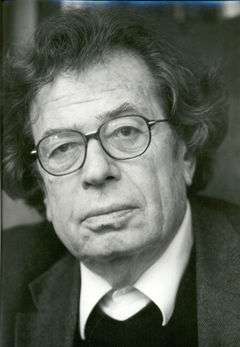

György Konrád

György (George) Konrád (born 2 April 1933) is a Hungarian novelist and essayist, known as an advocate of individual freedom.

Life

George Konrad (he prefers the English version of his name in translations) was born in Berettyóújfalu, near Debrecen into an affluent Jewish family. His father, József Konrád, was a successful hardware merchant; his mother, Róza Klein, came from the Nagyvárad Jewish middle class. His sister Éva was born in 1930. He graduated in 1951 from the Madách Secondary School in Budapest, entered the Lenin Institute and eventually studied literature, sociology and psychology at the Eötvös Loránd University. In 1956 he participated in the Hungarian Uprising against the Soviet occupation.

After the German occupation of Hungary, the Gestapo and Hungarian gendarmerie arrested his parents and deported them to Austria. The two children, together with two cousins, managed with difficulty to procure travel permits enabling them to visit their relatives in Budapest. The following day, every Jewish inhabitant of Berettyóújfalu was deported to the ghetto in Nagyvárad, and from there to Auschwitz. Konrád's classmates were, almost without exception, all killed in Birkenau. The two children and their cousins survived the Holocaust in a safe house under Swiss sponsorship .

At the end of February 1945, Eva and George returned to Berettyóújfalu. In June 1945, their parents returned home from deportation, and the Konrád family ultimately survived intact, the only such family among the some 1000 Jewish inhabitants of Berettyóújfalu. In 1950, when the state appropriated his father's business and the family residence, Konrád's parents moved in with their children studying in Budapest. The story of Konrád's survival as a child is told in his autobiographical novel Departure and Return (Hungarian version 2001).

He began his studies in 1946 at the Main Reformed Gimnázium in Debrecen, and from 1947 to 1951, he attended the Madách Gimnázium in Budapest. He completed his university education in the Department of Hungarian literature and language at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest in 1956.

During the 1956 Revolution, he was a member of the National Guard, which drew its ranks from university students. He moved through the city with a machine gun, motivated by curiosity more than anything else. He never used his weapon. His friends, his sister and his cousins emigrated to the West. Konrád chose to remain in the country.

He made his living through ad hoc jobs: he was a tutor, wrote reader reports, translated, and worked as a factory hand. Beginning in the summer of 1959, he secured steady employment as a children's welfare supervisor in Budapest's seventh District. He remained there for seven years, during which time he amassed the experiences that would serve as the basis for his novel The Case Worker (1969). The book drew a vigorous and mixed response: the official criticism was negative, but the book quickly became very popular and sold out in days.

Between 1960 and 1965 he was employed as a reader at the Magyar Helikon publishing house, where he was chief editor of works by Gogol, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Babel, and Balzac.

In 1965, he joined the Urban Science and Planning Institute, there undertaking research in urban sociology with the sociological research group of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He was working closely with urban sociologist Iván Szelényi with whom they wrote a book On the Sociological Problems of the New Housing Developments (1969) and two extensive works on the management of the country’s regional zones, as well as on urbanistic and ecological trends in Hungary.

His experiences as an urbanist provided material for his next novel, The City Builder, in which he radically extended the experiments in language and form that marked The Case Worker. The City Builder was allowed to appear in Hungarian only in censored form from Magvető Publishers in 1977. It was published abroad by Suhrkamp, Seuil, Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, and Philip Roth’s Penguin Series, with a foreword by Carlos Fuentes.

Konrád lost his job by order of the political police in July 1973. For half a year he worked as a nurse’s aide at the work-therapy-based mental institution at Doba.

Together with Iván Szelényi, Konrád published The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power in 1974. Shortly after the completion of The Intellectuals intended for foreign publication, the political police bugged and searched Szelényi’s and Konrád’s apartments. A significant part of Konrád’s diaries were confiscated and the authors were arrested for incitement against the state. They were placed on probation and informed that they would be permitted to emigrate with their families. Szelényi accepted the offer, while Konrád remained in Hungary, choosing internal emigration and all that it entailed. A smuggled manuscript of The Intellectuals on the Road to Class Power was published abroad and remains on university reading lists to this day.

He published in Hungarian samizdat and by publishers in the West. Virtually from this period until 1989, Konrád was a forbidden author in Hungary, deprived of all legal income. He made a living from honoraria abroad. His works were placed in restricted sections in libraries. Naturally he was also forbidden to speak on radio or television. The prohibition against travel expired in 1976.. Konrád then spent a year in Berlin on a DAAD fellowship, and another year in the United States on a stipend from his American publisher. During this period, he wrote his novel The Loser.

Between 1977 and 1982, two volumes of Konrád’s essays appeared: The Temptation of Autonomy (not translated into English) and Antipolitics. These works called into question the European political status quo. Antipolitics portrayed the Yalta Agreement and the spheres of influence system as the potential cause of a possible Third World War. The book’s subtitle was Central-European Meditations, and it was to become one of the voices demanding that region’s secession from the Soviet bloc as a requisite for peace in Europe. Konrád was one of the first to predict the imminent disappearance of the Iron Curtain. In 1984, he read his essay "Does the Dream of Central Europe Still Exist?" in the Schwarzenberg Palace as he received the Herder Prize from the University of Vienna. Critics have compared his essays to the writings of Adam Michnik, Milan Kundera, Václav Havel, Czeslaw Milos and Danilo Kiš.

The years between 1973 and 1989 witnessed the evolution of a dissident political and artistic subculture, independent of official culture. Konrád was one of the determining voices in the democratic opposition. His works appeared in the underground so called samizdat journals of the opposition. In interviews given to Radio Free Europe, Konrad’s ideas reached a wider Hungarian audience.

Beginning in September 1982, he was a year-long guest at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin; the following year he received a fellowship at the New York Institute for the Humanities. Over the four years that followed, Konrád wrote A Feast in the Garden (Hungarian version 1985). Now released from the official prohibition against publication, he sent the manuscript to the Magvető publishing house in Hungary.

In 1986 Konrad received an invitation from the Jerusalem Literary Fund, spending a month in that city. This was the period when Konrád primarily penned those essays and diary entries that would be collected for the volume The Invisible Voice (Hungarian version 1997). Konrád returned to Israel in 1992 and 1996. During his first visit he gave a long biographical interview for the University of Jerusalem, while on the second, he gave a lecture entitled "Judaism’s Three Paths" at the Ben Gurion University in Beer Sheva. In 1988 he taught world literature at Colorado College in Colorado Springs.

In the first years after the fall of the old regime, beginning in 1989, Konrád took an active part in public life in Hungary, and was one of the thinkers who paved the way for the transition to democracy. He was a founding member of the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ), and one of the founders and spokespeople for the Democratic Charter. He made frequent appearances in both the print and electronic media.

In the spring of 1990 Konrád was elected President of PEN International, holding this office for the full term until 1993. He made strenuous efforts on behalf of imprisoned and persecuted writers and called the writers of disintegrating nations together to roundtable conferences in the interest of peace.

Between 1997 and 2003, Konrád was twice elected President of Berlin’s Akademie der Künste. As the first foreigner to hold that post, Konrád was an effective contributor to the intellectual rapprochement between the East and West of Europe, and did much to introduce writers and other creative figures from Central Europe, and particularly from Hungary, to the West. His efforts were greeted by an appreciative German public. During his presidency, he received the Internationale Karlspreis zu Aachen (2001) and the Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (2003).

Though Konrád has frequently portrayed his Berettyóúfalu childhood in his novels, and particularly in The Feast in the Garden, he attempted to present this period in a more precise documentary form in two more recent books, Departure and Return (2001) and Up on the Hill During a Solar Eclipse (2003). The first of these books treats a single year – 1944-45 – while the second covers fifty, after beginning with a reflection on the final years of the twentieth century, more precisely the morning solar eclipse of 1999, experienced from the peak of St. György Hill. These books were published separately in Europe, and together in New York as A Guest in My Own Country (2007).

The year 2006 saw the publication of his volume Figures of Wonder, subtitled Portraits and Snapshots. These portraits are modeled primarily on friends, some still living – descriptions that constitute a continuation of the series presented by Konrád in his book The Writer and the City (2004) together with longer essays. His more recent books, The Roosters’ Sorrow (2005), Pendulum (2008), The Chimes (2009), and The Visitor’s Book (2013) present his philosophy of life with a near-poetic density.

Konrád has been married three times. In 1955 he married Vera Varsa, with whom he lived until 1963. In 1963 he married Júlia Lángh. They had two children, Anna Dóra in 1965, and Miklós István in 1967. Since 1979, Konrád has lived with Judit Lakner, his third wife. Together they have three children, Áron (1986), József (1987), and Zsuzsanna (1994).

Awards and Honors

Herder Prize (1983), Charles Veillon Prize (1985), Manes-Sperber Prize (1990), Kossuth Prize (1990) Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels (1991), Goethe Medal (2000), Internationale Karlspreis zu Aachen (2001), Franz Werfel Human Rights Award (2007), National Jewish Book Award in the memoir category (2008).

He has received the highest state distinctions awarded by France, Hungary, and Germany: Officier de l’Ordre national de la Légion d’Honneur (1996); The Hungarian Republic Legion of Honor Middle Cross with Star (2003); Das Grosse Verdienstkreuz des Bundesrepublik Deutschland (2003). He holds honorary doctorates from the University of Antwerp (1990) and the University of Novi Sad (2003). He is an honorary citizen of Berettyóújfalu (2003) and of Budapest (2004).

Bibliography

Partial list of works

Fiction

- The Case Worker

- The City Builder

- The Loser

- A Feast in the Garden

- The Stone Dial

Non-fiction

- The Intellectual on the Road to Class Power (1978), with Iván Szelényi

- Antipolitics

- The Melancholy of Rebirth (1995)

- The Invisible Voice: Meditations on Jewish Themes

- A jugoszláviai háború (és ami utána jöhet) (1999)

- Jugoslovenski rat i ono što posle može da usledi) (2000)

- A Guest in My Own Country: A Hungarian Life (2003)

Articles

- “The Intelligentsia and Social Structure”. Telos[1] 38 (Winter 1978-79). New York: Telos Press.

References

External links

- Homepage

- Biography

- "Chance Wanderings," an essay by Konrad on the 'revolutions' of 1989

- Petri Liukkonen. "György Konrád". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Archived from the original on 4 July 2013.

- PEN International

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Per Wästberg |

International President of PEN International 1990–1993 |

Succeeded by Ronald Harwood |