Sándor Petőfi

| Sándor Petőfi Petőfi Sándor (hu) Alexander Petrovics (la) | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Petőfi painted by Miklós Barabás | |

| Born |

1 January 1823 Kiskőrös, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire |

| Died |

31 July 1849 (aged 26)[1] Fehéregyháza, Grand Principality of Transylvania, Austrian Empire; (Now Albești, Romania) |

| Resting place | unknown |

| Occupation | poet, revolutionary |

| Language | Hungarian |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Period | 1842–1849 |

| Notable works | National Song, John the Valiant |

| Spouse | Júlia Szendrey |

| Children | Zoltán Petőfi |

Sándor Petőfi (born Petrovics;[2][3] Hungarian: Petőfi Sándor pronounced [ˈpɛtøːfi ˈʃaːndor]; Slovak: Alexander Petrovič;[2] Serbian: Александар Петровић; 1 January 1823 – most likely 31 July 1849[1]) was a Hungarian poet and liberal revolutionary. He is considered Hungary's national poet, and was one of the key figures of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. He is the author of the Nemzeti dal (National Song), which is said to have inspired the revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary that grew into a war for independence from the Austrian Empire. It is most likely that he died in the Battle of Segesvár, one of the last battles of the war.

Early life

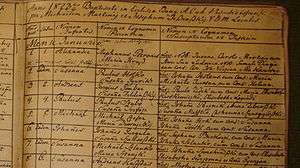

Petőfi was born in the early New Year's morning of 1823, in the town of Kiskőrös (Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Austrian Empire). The population of Kiskőrös was predominantly of Slovak origin as a consequence of the Habsburgs' reconstruction policy designed to settle, where possible, non-Hungarians in areas devastated during the Turkish wars.[4] His birth certificate in Latin, gives his name as "Alexander Petrovics",[2][3] where "Alexander" is the Latin equivalent of the Hungarian "Sándor". His father, István (Stefan) Petrovics, was a village butcher, innkeeper and he was a second-generation Serb[5][6] or Slovak[1][7][8] immigrant to the Great Hungarian Plain.[9] Mária Hrúz, Petőfi's mother, was a servant and laundress before her marriage. She was of Slovak descent and spoke Hungarian with something of an accent.[4][10][11] Petőfi's parents first met in Maglód, married in Aszód and the family moved to Kiskőrös a year before the birth of the poet.[4]

The family lived for some time in Szabadszállás, where his father owned a slaughterhouse. Within two years, the family moved to Kiskunfélegyháza, and Petőfi always viewed the city as his true home. His father tried to give his son the best possible education and sent him to a lyceum, but when Sándor was 15, the family went through a financially difficult period, due to the Danube floods of 1838 and the bankruptcy of a relative. Sándor had to leave the lyceum which he was attending in Selmecbánya (today Banská Štiavnica in Slovakia). He held small jobs in various theatres in Pest, worked as a teacher in Ostffyasszonyfa, and was a soldier in Sopron.

After a restless period of travelling, Petőfi attended college at Pápa, where he met Mór Jókai. A year later in 1842, his poem "A borozó" (The Wine Drinker) was first published in Athenaeum under the name Sándor Petrovics. On 3 November the same year, he published the poem under the surname "Petőfi" for the first time.

Petőfi was more interested in the theatre. In 1842 he joined a travelling theatre, but had to leave it to earn money. He wrote for a newspaper, but could not make enough money. Malnourished and sick, he went to Debrecen, where his friends helped him get back on his feet.

In 1844 he walked from Debrecen to Pest to find a publisher for his poems and he succeeded. His poems were becoming increasingly popular. He relied on folkloric elements and popular, traditional song-like verses.

Among his longer works is the epic "John the Valiant" (1845). The poem is a fairy-tale notable for its length, 370 quatrains divided into 27 chapters, and for its clever wordplay. It has gained immense popularity in Hungary,[note 1] however, he felt influenced by his editor, Imre Vahot, to continue writing folklore-style poems, while he wanted to use his Western-oriented education and write about growing revolutionary passions. (The government's censorship would have made such works difficult to publish.)

Marriage and family

In 1846, he met Júlia Szendrey in Transylvania. They married the next year, despite the opposition of her father, and spent their honeymoon at the castle of Count Sándor Teleki (hu), the only aristocrat among Petőfi's friends. Their only son Zoltán was born on 15 December 1848.[12]

Political career

Petőfi became more possessed by thoughts of a global revolution. He and Júlia moved to Pest, where he joined a group of like-minded students and intellectuals who regularly met at Café Pilvax. They worked on promoting Hungarian as the language of literature and theatre, formerly based on German.[13] The first permanent Hungarian theatre (Pesti Magyar Színház), which later became the National Theater, was opened in that time (1837).

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848

Among the various young leaders of the revolution, called Márciusi Ifjak (Youths of March), Petőfi was the key in starting the revolution in Pest. He was co-author and author, respectively, of the two most important written documents: the 12 Pont (12 Points, demands to the Habsburg Governor-General) and the "Nemzeti Dal", his revolutionary poem.

When the news of the revolution in Vienna reached them on the 15th, Petőfi and his friends decided to change the date of the "National Assembly" (a rally where a petition to the Hungarian noblemen's assembly would be approved by the people), from 19 March to the 15th. On the morning of the 15th, Petőfi and the revolutionaries began to march around the city of Pest, reading his poem and the "12 Points" to the growing crowd, which attracted thousands. Visiting printers, they declared an end to censorship and printed the poem and "12 Points".

Crowds forced the mayor to sign the "12 Points" and later held a mass demonstration in front of the newly built National Museum, then crossed to Buda on the other bank of the Danube. When the crowd rallied in front of the Imperial governing council, the representatives of Emperor Ferdinand felt they had to sign the "12 Points". As one of the points was freedom for political prisoners, the crowd moved to greet the newly freed revolutionary poet Mihály Táncsics.

Petőfi's popularity waned as the memory of the glorious day faded, and the revolution went the way of high politics: to the leadership of the nobles. Those in the noblemen's Assembly in Pozsony, (today Bratislava) had been pushing for slower reforms at the same time, which they delivered to the Emperor on the 13th, but events had overtaken them briefly. Petőfi disagreed with the Assembly, and criticised their view of the goals and methods of the Revolution. (His colleague Táncsics was imprisoned again by the new government.) In the general election, Petőfi ran in his native area, but did not win a seat. At this time, he wrote his most serious poem, Az Apostol (The Apostle). It was an epic about a fictional revolutionary who, after much suffering, attempts, but fails, to assassinate a fictitious king.

Petőfi joined the Hungarian Revolutionary Army and fought under the Polish Liberal General Józef Bem, in the Transylvanian army. The army was initially successful against Habsburg troops, but after Tsar Nicholas I of Russia intervened to support the Habsburgs, they were defeated. Petőfi was last seen alive in the Battle of Segesvár on 31 July 1849.

Death

Petőfi is believed to have been killed in action during the battle of Segesvár by the Imperial Russian Army. A Russian military doctor recorded an account of Petőfi's death in his diary. As his body was never officially found, rumours of Petőfi's survival persisted. In his autobiographical roman a clef Political Fashions (Politikai divatok, 1862), Mór Jókai imagined his late friend's "resurrection". In the novel Petőfi (the character named Pusztafi) returns ten years later as a shabby, déclassé figure who has lost his faith in everything, including poetry.

Though for many years his death at Segesvár had been assumed, in the late 1980s Soviet investigators found archives that revealed that after the battle about 1,800 Hungarian prisoners of war were marched to Siberia. Alternative theories suggest that he was one of them and died of tuberculosis in 1856.[14] In 1990, an expedition was organised to Barguzin, Siberia, where archaeologists claimed to have unearthed Petőfi's skeleton.[15]

Poetry

Petőfi started his career as a poet with "popular situation songs", a genre to which his first published poem, A borozó ("The Wine Drinker", 1842), belongs. It is the song of a drinker praising the healing power of wine to drive away all troubles. This kind of pseudo-folk song was not unusual in Hungarian poetry of the 1840s, but Petőfi soon developed an original and fresh voice which made him stand out. He wrote many folk song-like poems on the subjects of wine, love, romantic robbers etc. Many of these early poems have become classics, for example the love poem A virágnak megtiltani nem lehet ("You Cannot Forbid the Flower", 1843), or Befordultam a konyhára ("I Turned into the Kitchen", 1843) which uses the ancient metaphor of love and fire in a playful and somewhat provocative way.

The influence of folk poetry and 19th-century populism is very significant in Petőfi's work, but other influences are also present: Petőfi drew on sources such as topoi of contemporary almanac-poetry in an inventive way, and was familiar with the works of major literary figures of his day, including Percy Bysshe Shelley, Pierre-Jean de Béranger and Heinrich Heine.

Petőfi's early poetry was often interpreted as some kind of role-playing, due to the broad range of situations and voices he created and used. Recent interpretations however call attention to the fact that in some sense all lyrical poetry can be understood as role-playing, which makes the category of "role-poems" (coined especially for Petőfi) superfluous. While using a variety of voices, Petőfi created a well-formed persona for himself: a jaunty, stubborn loner who loves wine, hates all kinds of limits and boundaries and is passionate in all he feels. In poems such as Jövendölés ("Prophecy", 1843) he imagines himself as someone who will die young after doing great things. This motif recurs in the revolutionary poetry of his later years.

The influence of contemporary almanac-poetry can be best seen in the poem cycle Cipruslombok Etelke sírjára ("Branches of Cypress for Etelke's Tomb", 1845). These sentimental poems, which are about death, grief, love, memory and loneliness were written after a love interest of Petőfi's, Etelke Csapó, died.

In the years 1844–45 Petőfi's poetry became more and more subtle and mature. New subjects appeared, such as landscape. His most influential landscape poem is Az Alföld ("The Plains"), in which he says that his homeland, the Hungarian plains are more beautiful and much dearer than the Carpathian mountains; it was to become the foundation of a long-lived fashion: that of the plains as the typical Hungarian landscape.

Petőfi's poetic skills solidified and broadened. He became a master of using different kinds of voices, for example his poem A régi, jó Gvadányi ("The Good Old Gvadányi") imitates the style of József Gvadányi, a Hungarian poet who lived at the end of the 18th century.

It is interesting to note that several of Petőfi's poems were set to music by the young Friedrich Nietzsche, who composed as a hobby while studying classics at Pforta before beginning his career in philosophy.

Petőfi maintained a lifelong friendship with János Arany, another significant poet of the time. Arany was the godfather of Petőfi's son Zoltán.

Honours and memorials

After the Revolution was crushed, Petőfi's writing became immensely popular, while his rebelliousness served as a role model ever since for Hungarian revolutionaries and would-be revolutionaries of every political colour.

Hungarian composer and contemporary Franz Liszt composed the piano piece Dem Andenken Petőfis (In Petőfi's Memory) in his honour. Liszt has also set several of Petőfi's poems to music.

In 1911, a statue of Sándor Petőfi was erected in the Slovak capital of Bratislava, on the Main Square. In 1918, after the army of the newly independent First Czechoslovak Republic occupied the city, the statue was dynamited.[16][17] After this sculpture was boarded over round temporarily until its removal, and replaced with a statue of Slovak poet Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav.[18] Today, there is a statue of Petőfi in the Medic Garden (Medická záhrada).[19]

During the late 1940s, Boris Pasternak produced acclaimed translations of Petőfi's poems into the Russian language.

Today, streets and squares are named after him throughout Hungary and Hungarian-speaking regions of neighbouring states; in Budapest alone, there are 11 Petőfi streets and 4 Petőfi squares, see: Public place names of Budapest. A national radio station (Radio Petőfi), a bridge in Budapest and a street in Sofia, Bulgaria also bear his name, as well as the asteroid 4483 Petöfi, a member of the Hungaria family.

Petőfi has a larger than life terra cotta statue near the Pest end of Erzsébet Bridge, sculpted by Miklós Izsó and Adolf Huszár. Similar Petőfi statues were established in many other cities, as well, during the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.[20]

Hugó Meltzl was who made well known the works of Sándor Petőfi in abroad. [note 2]

Notes

- ↑ It has several musical and film adaptations and is today considered a classic of Hungarian literature.

- ↑ E.g. Petőfi, Gedichte. München, 1867; Petőfi's Wolken. Lübeck, 1882; Petőfi's ausgewählte Gedichte. München, 1883.

References

- 1 2 3 Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon 1000–1990. Mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 LUCINDA MALLOWS, BRADT TRAVEL GUIDE BRATISLAVA, THE, Bradt Travel Guides, 2008, p. 7

- 1 2 Sándor Petőfi, George Szirtes, John the Valiant, Hesperus Press, 2004, p. 1

- 1 2 3 Anton N. Nyerges, Petőfi, Hungarian Cultural Foundation, 1973, pp. 22–197

- ↑ Vesti – Na današnji dan, 31. jul. B92 (31 July 2006). Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Kahn, Robert, A. A history of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918.

- ↑ Élet És Irodalom. Es.hu (16 May 2010). Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Nemzetközi Magyar Filológiai Társaság (1996). Hungarian studies: HS., Volumes 11–12. Akadémiai Kiadó,.

- ↑ Rein Taagepera, The Finno-Ugric republics and the Russian state, Routledge, 1999, p. 84

- ↑ Sandor Petofi. Budapestguide.uw.hu. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Illyés Gyula: Petőfi Sándor. Mek.iif.hu. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Petőfi Zoltán. 40 felett. retrieved on 15 March 2012.

- ↑ A PESTI MAGYAR SZÍNHÁZ ÉPÍTÉSE ÉS MEGSZERVEZÉSE György Székely – Ferenc Kerényi (eds.): MAGYAR SZÍNHÁZTÖRTÉNET 1790–1873. Chapter I.III.4. Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó 1990

- ↑ Sandor Petofi (Hungarian poet) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. Retrieved on 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Adam Makkai (1996). In Quest of the 'Miracle Stag'. University of Illinois Press. p. 298. ISBN 0-9642094-0-3.

- ↑ "A vándorló Petőfi". Madách-Posonium Kft. n.d. Retrieved 20 July 2008.

- ↑ Ferenc Keszeli, "Pozsony... Anno... Századfordulós évtizedek, hangulatok képes levelezõlapokon ", p. 122, p. 150, p. 154 (Hungarian)

- ↑ Ferenc Keszeli, "Pozsony... Anno... Századfordulós évtizedek, hangulatok képes levelezõlapokon ", p. 150, p. 154 (Hungarian)

- ↑ Mallows, Lucinda. Bratislava. p. 191. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer, HISTORY OF THE LITERARY CULTURES OF EAST-CENTRAL E, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2010, pp 15–16

External links

-

Media related to Sándor Petőfi at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sándor Petőfi at Wikimedia Commons - Sándor Petőfi on a Hungarian banknote from 1957

- Complete works (in Hungarian)

- Morvai's expedition (in Slovak)

- Works by Sándor Petőfi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Sándor Petőfi at Internet Archive

- Works by Sándor Petőfi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)