Hellenistic art

the Winged Victory of Samothrace, from the island of Samothrace, 200-190 BC, Louvre

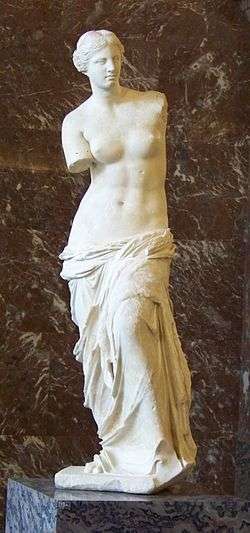

the Venus de Milo, discovered at the Greek island of Milos, 130-100 BC, Louvre

Pergamon Altar, Pergamon Museum, Berlin.

Hades abducting Persephone, fresco in the royal tomb at Vergina, Macedonia, Greece, c. 340 BC

Hellenistic art is the art of the period in classical antiquity generally taken to begin with the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, a process well underway by 146 BCE, when the Greek mainland was taken, and essentially ending in 31 BCE with the conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt following the Battle of Actium. A number of the best-known works of Greek sculpture belong to this period, including Laocoön and His Sons, Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. It follows the period of Classical Greek art, while the succeeding Greco-Roman art was very largely a continuation of Hellenistic trends.

The term Hellenistic refers to the expansion of Greek influence and dissemination of its ideas following the death of Alexander – the "Hellenizing" of the world,[1] with Koine Greek as a common language.[2] The term is a modern invention; the Hellenistic World not only included a huge area covering the whole of the Aegean, rather than the Classical Greece focused on the Poleis of Athens and Sparta, but also a huge time range. In artistic terms this means that there is huge variety which is often put under the heading of "Hellenistic Art" for convenience.

One of the defining characteristics of the Hellenistic period was the division of Alexander's empire into smaller dynastic empires founded by the diadochi (Alexander's generals who became regents of different regions): the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in Mesopotamia, Persia, and Syria, the Attalids in Pergamon, etc. Each of these dynasties practiced a royal patronage which differed from those of the city-states.

In Alexander's entourage were three artists: Lysippus the sculptor, Apelles the painter, and Pyrgoteles the gem cutter and engraver.[3] The period after his death was one of great prosperity and considerable extravagance for much of the Greek world, at least for the wealthy. Royalty became important patrons of art. Sculpture, painting and architecture thrived, but vase-painting ceased to be of great significance. Metalwork and a wide variety of luxury arts produced much fine art. Some types of popular art were increasingly sophisticated.

There has been a trend in writing history to depict Hellenistic art as a decadent style, following the Golden Age of Classical Greece. The 18th century terms Baroque and Rococo have sometimes been applied to the art of this complex and individual period. A renewed interest in historiography as well as some recent discoveries, such as the tombs of Vergina, may allow a better appreciation of the period.

Architecture

In the architectural field, the dynasties following Hector resulted in vast urban plans and large complexes which had mostly disappeared from city-states by the 5th century BC.[4] The Doric Temple was virtually abandoned.[5] This city planning was quite innovative for the Greek world; rather than manipulating space by correcting its faults, building plans conformed to the natural setting. One notes the appearance of many places of amusement and leisure, notably the multiplication of theatres and parks. The Hellenistic monarchies were advantaged in this regard in that they often had vast spaces where they could build large cities: such as Antioch, Pergamon, and Seleucia on the Tigris.

It was the time of gigantism: thus it was for the second temple of Apollo at Didyma, situated twenty kilometers from Miletus in Ionia. It was designed by Daphnis of Miletus and Paionios of Ephesus at the end of the fourth century BC, but the construction, never completed, was carried out up until the 2nd century AD. The sanctuary is one of the largest ever constructed in the Mediterranean region: inside a vast court (21.7 metres by 53.6 metres), the cella is surrounded by a double colonnade of 108 Ionic columns nearly 20 metres tall, with richly sculpted bases and capitals.[6]

Athens

The Corinthian order was used for the first time on a full-scale building at the Temple of Olympian Zeus.[7]

Pergamon

Pergamon in particular is a characteristic example of Hellenistic architecture. Starting from a simple fortress located on the Acropolis, the various Attalid kings set up a colossal architectural complex. The buildings are fanned out around the Acropolis to take into account the nature of the terrain. The agora, located to the south on the lowest terrace, is bordered by galleries with colonnades (columns) or stoai. It is the beginning of a street which crosses the entire Acropolis: it separates the administrative, political and military buildings on the east and top of the rock from the sanctuaries to the west, at mid-height, among which the most prominent is that which shelters the monumental Pergamon Altar, known as "of the twelve gods" or "of the gods and of the giants", one of the masterpieces of Greek sculpture. A colossal theatre, able to contain nearly 10,000 spectators, has benches embedded in the flanks of the hill.[8]

Sculpture

Pliny the Elder, after having described the sculpture of the classical period notes: Cessavit deinde ars ("then art disappeared").[9] According to Pliny's assessment, sculpture declined significantly after the 121st Olympiad (296-293 BC). A period of stagnation followed, with a brief revival after the 156th (156-153 BC), but with nothing to the standard of the times preceding it.[10]

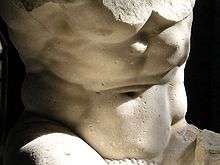

During this period sculpture became more naturalistic, and also expressive; there is an interest in depicting extremes of emotion. On top of anatomical realism, the Hellenistic artist seeks to represent the character of his subject, including themes such as suffering, sleep or old age. Genre subjects of common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens; the Boy with Thorn is an example.

Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.[11] The world of Dionysus, a pastoral idyll populated by satyrs, maenads, nymphs and Sileni, had been often depicted in earlier vase painting and figurines, but rarely in full-size sculpture. The drunk woman at Munich portrays without reservation an old woman, thin, haggard, clutching against herself her jar of wine.[12]

Portraiture

The period is therefore notable for its portraits: One such is the Barberini Faun of Munich, which represents a sleeping satyr with relaxed posture and anxious face, perhaps the prey of nightmares. The Belvedere Torso, the Resting Satyr, the Furietti Centaurs and Sleeping Hermaphroditus reflect similar ideas.[13]

Another famous Hellenistic portrait is that of Demosthenes by Polyeuktos, featuring a well-done face and clasped hands.[10]

Privatization

Another phenomenon of the Hellenistic age appears in its sculpture: privatization,[14][15] seen in the recapture of older public patterns in decorative sculpture.[16] Portraiture is tinged with naturalism, under the influence of Roman art.[17] New Hellenistic cities were springing up all over Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia, which required statues depicting the gods and heroes of Greece for their temples and public places. This made sculpture, like pottery, an industry, with the consequent standardization and some lowering of quality. For these reasons many more Hellenistic statues have survived than is the case with the Classical period.

Second classicism

Hellenistic sculpture repeats the innovations of the so-called "second classicism": nude sculpture-in-the-round, allowing the statue to be admired from all angles; study of draping and effects of transparency of clothing, and the suppleness of poses.[18] Thus, Venus de Milo, even while echoing a classic model, is distinguished by the twist of her hips.

"Baroque"

The multi-figure group of statues was a Hellenistic innovation, probably of the 3rd century, taking the epic battles of earlier temple pediment reliefs off their walls, and placing them as life-size groups of statues. Their style is often called "baroque", with extravagantly contorted body poses, and intense expressions in the faces.

Pergamon

Pergamon did not distinguish itself with its architecture alone: it was also the seat of a brilliant school of sculpture known as Pergamene Baroque.[19] The sculptors, imitating the preceding centuries, portray painful moments rendered expressive with three-dimensional compositions, often V-shaped, and anatomical hyper-realism. The Barberini Faun is one example.

Gauls

Attalus I (269-197 BC), to commemorate his victory at Caicus against the Gauls — called Galatians by the Greeks — had two series of votive groups sculpted: the first, consecrated on the Acropolis of Pergamon, includes the famous Gaul killing himself and his wife, of which the original is lost; the second group, offered to Athens, is composed of small bronzes of Greeks, Amazons, gods and giants, Persians and Gauls.[20] Artemis Rospigliosi in the Louvre is probably a copy of one of them; as for copies of the Dying Gaul, they were very numerous in the Roman period. The expression of sentiments, the forcefulness of details — bushy hair and moustaches here — and the violence of the movements are characteristic of the Pergamene style.[21]

Great Altar

These characteristics are pushed to their peak in the friezes of the Great Altar of Pergamon, decorated under the order of Eumenes II (197-159 BC) with a gigantomachy stretching 110 metres in length, illustrating in the stone a poem composed especially for the court. The Olympians triumph in it, each on his side, over Giants – most of which are transformed into savage beasts: serpents, birds of prey, lions or bulls. Their mother Gaia comes to their aid, but can do nothing and must watch them twist in pain under the blows of the gods.[22]

Colossus of Rhodes

One of the few city states who managed to maintain full independence from the control of any Hellenistic kingdom was Rhodes. After holding out for one year under siege by Demetrius Poliorcetes (305-304 BCE), the Rhodians built the Colossus of Rhodes to commemorate their victory.[23] With a height of 32 meters, it was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Progress in bronze casting made it possible for the Greeks to create large works. Many of the large bronze statues were lost — with the majority being melted to recover the material.

Laocoön

Discovered in Rome in 1506 and seen by Michelangelo,[24] Laocoön, strangled by snakes, tries desperately to loosen their grip without affording a glance at his dying sons, is attributed by Pliny the Elder to the Rhodian sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus.[24]

.jpg)

Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art, drew inspiration from the Laocoön. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing based many of the ideas in his 'Laocoon' (1766) on Winckelmann's views on harmony and expression in the visual arts.[25]

Sperlonga

The Sperlonga sculptures are another series of "baroque" sculptures in the Hellenistic style.[24] The inscriptions suggest the same sculptors made it who made the Laocoön group.[26]

Neo-Attic

From the 2nd century the Neo-Attic or Neo-Classical style is seen by different scholars as either a reaction to baroque excesses, returning to a version of Classical style, or as a continuation of the traditional style for cult statues.[27] Workshops in the style became mainly producers of copies for the Roman market, which preferred copies of Classical rather than Hellenistic pieces.[28]

_(12853680765).jpg) Fragment of a marble relief depicting a Kore, 3rd century BC, from Panticapaeum, Taurica (Crimea), Bosporan Kingdom

Fragment of a marble relief depicting a Kore, 3rd century BC, from Panticapaeum, Taurica (Crimea), Bosporan Kingdom- Gravestone of a woman with her child slave attending to her, c. 100 BC (early period of Roman Greece)

Late Hellenistic bronze of a mounted jockey, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Late Hellenistic bronze of a mounted jockey, National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Aphrodite and Eros fighting off the advances of Pan. Marble, hellenistic artwork from the late 2nd century BC.

Aphrodite and Eros fighting off the advances of Pan. Marble, hellenistic artwork from the late 2nd century BC..jpg) Hellenistic sculpture fragments from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Hellenistic sculpture fragments from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens- The Poseidon of Melos, from the National Archaeological Museum, Athens.

Paintings and mosaics

Wall painting

Few examples of Greek wall or panel paintings have survived the centuries. Researchers have been limited to studying the Hellenistic influences in Roman frescoes, for example those of Pompeii or Herculaneum. Some of the paintings in Villa Boscoreale clearly echo lost Hellenistic, Macedonian royal paintings.[29]

Landscape

Perhaps the most striking element of Hellenistic painting is the increased use of landscape.[30]

Recent discoveries

Recent discoveries include those of Macedonian chamber tombs,[30] and the recently-restored 1st-century Nabataean ceiling frescoes in the Painted House at Little Petra in Jordan.[31]

Recent archaeological discoveries at the cemetery of Pagasae (close to modern Volos), at the edge of the Pagasetic Gulf, or again at Vergina (1987), in the former kingdom of Macedonia, have brought to light some original works. For example, the tomb supposedly that of Philip II has provided a great frieze representing a royal lion hunt, remarkable by its composition, the arrangement of the figures in space and its realistic representation of nature.[32] In the 1960s, a group of wall paintings was found on Delos.[33]

Mosaics

Certain mosaics, however, provide a pretty good idea of the "grand painting" of the period: these are copies of frescoes.

Alexander mosaic

An example is the Alexander Mosaic, showing the confrontation of the young conqueror and the Grand King Darius III at the Battle of Issus, a mosaic from a floor in the House of the Faun at Pompeii (now in Naples). It is believed to be a copy of a painting described by Pliny which had been painted by Philoxenus of Eretria for King Cassander of Macedon at the end of the 4th century BC,[34] or even of a painting by Apelles contemporaneous with Alexander himself.[35] The mosaic allows us to admire the choice of colours, the composition of the ensemble with turning movement and facial expression.

Stag Hunt mosaic

The Stag Hunt Mosaic by Gnosis is a mosaic from a wealthy home of the late 4th century BC, the so-called "House of the Abduction of Helen" (or "House of the Rape of Helen"), in Pella, The signature ("Gnosis epoesen", i.e. Gnosis created) is the first known signature of a mosaicist.[36]

The emblema is bordered by an intricate floral pattern, which itself is bordered by stylized depictions of waves.[38] The mosaic is a pebble mosaic with stones collected from beaches and riverbanks which were set into cement.[38] As was perhaps often the case,[39] the mosaic does much to reflect styles of painting.[40] The light figures against a darker background may allude to red figure painting.[40] The mosaic also uses shading, known to the Greeks as skiagraphia, in its depictions of the musculature and cloaks of the figures.[40] This along with its use of overlapping figures to create depth renders the image three dimensional.

Nile mosaic of Palestrina

The Nile mosaic of Palestrina is a late Hellenistic floor mosaic depicting the Nile in its passage from Ethiopia to the Mediterranean.

Sosos

The Hellenistic period is equally the time of development of the mosaic as such, particularly with the works of Sosos of Pergamon, active in the 2nd century BC and the only mosaic artist cited by Pliny.[41] His taste for trompe l'oeil (optical illusion) and the effects of the medium are found in several works attributed to him such as the "Unswept Floor" in the Vatican museum,[42] representing the leftovers of a repast (fish bones, bones, empty shells, etc.) and the "Dove Basin" at the Capitoline Museum, known by means of a reproduction discovered in Hadrian's Villa.[6] In it one sees four doves perched on the edge of a basin filled with water. One of them is watering herself while the others seem to be resting, which creates effects of reflections and shadow perfectly studied by the artist.

%2C_Ancient_Pella_(6913935544).jpg) Central panel of the Abduction of Helen of Troy by Theseus, floor mosaic, detail of the charioteer, from the House of the Abduction of Helen, (c. 300 BC), ancient Pella

Central panel of the Abduction of Helen of Troy by Theseus, floor mosaic, detail of the charioteer, from the House of the Abduction of Helen, (c. 300 BC), ancient Pella A Macedonian mosaic of the Kasta Tomb in Amphipolis depicting the abduction of Persephone by Pluto, 4th century BC

A Macedonian mosaic of the Kasta Tomb in Amphipolis depicting the abduction of Persephone by Pluto, 4th century BC An ancient fresco of Macedonian soldiers from the tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, Greece, 4th century BC

An ancient fresco of Macedonian soldiers from the tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, Greece, 4th century BC An ancient fresco of Macedonian soldiers from the tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, Greece, 4th century BC

An ancient fresco of Macedonian soldiers from the tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, Greece, 4th century BC Hellenistic soldiers circa 100 BCE, Ptolemaic Kingdom, Egypt; detail of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina.

Hellenistic soldiers circa 100 BCE, Ptolemaic Kingdom, Egypt; detail of the Nile mosaic of Palestrina. A stele of Dioskourides, dated 2nd century BC, showing a Ptolemaic thureophoros soldier (wielding the thureos shield). It is a characteristic example of the "romanization" of the Ptolemaic army.

A stele of Dioskourides, dated 2nd century BC, showing a Ptolemaic thureophoros soldier (wielding the thureos shield). It is a characteristic example of the "romanization" of the Ptolemaic army.

Ceramics

The most common vases of the period are black and uniform, with a shiny appearance approaching that of varnish, decorated with simple motifs of flowers or festoons. The shapes of the vessels are often based on metalwork shapes: thus with the lagynos, a wine jar typical of the period.

Hellenistic pottery designs can be found in the city of Taxila in modern Pakistan, which was colonized with Greek artisans and potters after Alexander conquered it.

Megarian ware

It is also the period of so-called Megarian ware:[43] mold-made vases with decoration in relief appeared, doubtless in imitation of vases made of precious metals. Wreaths in relief were applied to the body of the vase. One finds also more complex relief, based on animals or mythological creatures.

Vase painting

The Hellenistic period is that of the decline of vase-painting, with the notable exception of Hadra vases and Panathenaic amphora. Fine painted pottery was apparently replaced by metalwork for many of its uses.

West Slope ware

Red-figure painting had died out in Athens by the end of the 4th century BC to be replaced by what is known as West Slope Ware, so named after the finds on the west slope of the Athenian Acropolis. This consisted of painting in a tan coloured slip and white paint on a fired black slip background with some incised detailing.[44]

Representations of people diminished, replaced with simpler motifs such as wreaths, dolphins, rosettes, etc. Variations of this style spread throughout the Greek world with notable centres in Crete and Apulia, where figural scenes continued to be in demand.

Apulian

Gnathia vases

Gnathia vases however were still produced not only in Apulian, but also in Campanian, Paestan and Sicilian vase painting.

Canosa ware

In Canosa di Puglia in South Italy, in 3rd century BC burials one might find vases with fully three-dimensional attachments.[45] The distinguishing feature of Canosa vases are the water-soluble paints. Blue, red, yellow, light purple and brown paints were applied to a white ground.

Centuripe ware

The Centuripe ware of Sicily "the last gasp of Greek vase painting",[1] had fully coloured tempera painting including groups of figures applied after firing, contrary to the traditional practice. The fragility of the pigments prevented frequent use of these vases; they were reserved for use in funerals. The practice perhaps continued into the 2nd century BC, making it possibly the last vase painting with significant figures.[46] A workshop was active until at least the 3rd century BC. These vases are characterized by a base painted pink. The figures, often female, are represented in coloured clothing: blue-violet chiton, yellow himation, white veil. The style is reminiscent of Pompeii and draws more from grand contemporary paintings than on the heritage of the red-figure pottery.

Terracotta figurines

Bricks and tiles were used for architectural and other purposes. Production of Greek terracotta figurines became increasingly important. Terracotta figurines represented divinities as well as subjects from contemporary life. Previously reserved for religious use, in Hellenistic Greece the terracotta was more frequently used for funerary and purely decorative, purposes. The refinement of molding techniques made it possible to create true miniature statues, with a high level of detail, typically painted.

Several Greek styles continued into the Roman period, and Greek influence, partly transmitted via the Ancient Etruscans, on Ancient Roman pottery was considerable, especially in figurines.

Tanagra figurines

Tanagra figurines, from Tanagra in Boeotia and other centers, full of lively colours, most often represent elegant women in scenes full of charm.[47] At Smyrna, in Asia Minor, two major styles occurred side-by-side: first of all, copies of masterpieces of great sculpture, such as the Farnese Hercules in gilt terracotta.

Grotesques

In a completely different genre, there are the "grotesques", which contrast violently with the canons of "Greek beauty": the koroplathos (figurine maker) fashions deformed bodies in tortuous poses — hunchbacks, epileptics, hydrocephalics, obese women, etc. One could therefore wonder whether these were medical models, the town of Smyrna being reputed for its medical school. Or they could simply be caricatures, designed to provoke laughter. The "grotesques" are equally common at Tarsus and also at Alexandria.

Negro

One theme which emerged was the "negro", particularly in Ptolemaic Egypt: these statuettes of Black adolescents were successful up to the Roman period.[48] Sometimes, they were reduced to echoing a form from the great sculptures: thus one finds numerous copies in miniature of the Tyche (Fortune or Chance) of Antioch, of which the original dates to the beginning of the 3rd century BC.

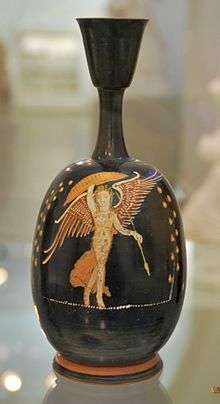

A bottle (Lekythos) in Gnathia style - Eros, with a painting depicting a figure playing with a ball, Apulia (Magna Graecia), Italy, third quarter of the 4th century BC

A bottle (Lekythos) in Gnathia style - Eros, with a painting depicting a figure playing with a ball, Apulia (Magna Graecia), Italy, third quarter of the 4th century BC Krater, Apulian vase painting with relief decorations, 330-320 BC

Krater, Apulian vase painting with relief decorations, 330-320 BC A sphageion with gorgoneions, from South Italy, Canosa di Puglia, late 4th to early 3rd century BC, clay, slip, paint. Pushkin Museum, Moscow

A sphageion with gorgoneions, from South Italy, Canosa di Puglia, late 4th to early 3rd century BC, clay, slip, paint. Pushkin Museum, Moscow- An askos in the shape of a woman's head, 270-200 BC, from Canosa di Puglia

.jpg) Female head partially imitating a vase (lekythos), 325-300 BC.

Female head partially imitating a vase (lekythos), 325-300 BC.- Ancient greek terracotta head of a young man, found in Tarent, ca. 300 BC, Antikensammlung Berlin.

Tanagra figurine playing a pandura, 200 BC

Tanagra figurine playing a pandura, 200 BC

Minor arts

Metallic art

Because of so much bronze statue melting, only the smaller objects still exist. In Hellenistic Greece, the raw materials were plentiful following eastern conquests.

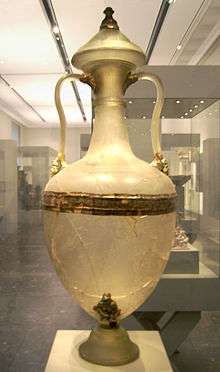

The work on metal vases took on a new fullness: the artists competed among themselves with great virtuosity. The Thracian Panagyurishte Treasure (from modern Bulgaria), includes Greek objects such as a gold amphora with two rearing centaurs forming the handles.

The Derveni Krater, from near Thessaloniki, is a large bronze volute krater from about 320 BC, weighing 40 kilograms, and finely decorated with a 32-centimetre-tall frieze of figures in relief representing Dionysus surrounded by Ariadne and her procession of satyrs and maenads.[49] The neck is decorated with ornamental motifs while four satyrs in high relief are casually seated on the shoulders of the vase.

The evolution is similar for the art of jewellery. The jewellers of the time excelled at handling details and filigrees: thus, the funeral wreaths present very realistic leaves of trees or stalks of wheat. In this period the insetting of precious stones flourished.

Glass and glyptic art

It was in the Hellenistic period that the Greeks, who until then only knew molded glass, discovered the technique of glass blowing, thus permitting new forms. Beginning in Syria,[50] the art of glass developed especially in Italy. Molded glass continued, notably in the creation of intaglio jewelry.

The art of engraving gems hardly advanced at all, limiting itself to mass-produced items that lacked originality. As compensation, the cameo made its appearance. It concerns cutting in relief on a stone composed of several colored layers, allowing the object to be presented in relief with more than one color. The Hellenistic period produced some masterpieces like the Gonzaga cameo, now in the Hermitage Museum, and spectacular hardstone carvings like the Cup of the Ptolemies in Paris.[51]

Coinage

Coinage in the Hellenistic period increasingly used portraits.[52]

The golden larnax of Philip II of Macedon which contained his remains. It was constructed in 336 BC. It weighs 11 kilos and is made of 24 carat gold. Vergina, Greece.

The golden larnax of Philip II of Macedon which contained his remains. It was constructed in 336 BC. It weighs 11 kilos and is made of 24 carat gold. Vergina, Greece. The golden wreath of Philip II found inside the golden larnax. It weighs 717 grams.

The golden wreath of Philip II found inside the golden larnax. It weighs 717 grams.- Golden jewellery to be worn as hair ornaments, 3rd century BC, Stathatos Collection, National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

The Gonzaga Cameo 3rd century BC, in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

The Gonzaga Cameo 3rd century BC, in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg Apollonios of Athens, gold ring with portrait in garnet, c. 220 BC

Apollonios of Athens, gold ring with portrait in garnet, c. 220 BC

Later Roman copies

Spurred by the Roman acquisition, elite consumption and demand for Greek art, both Greek and Roman artists, particularly after the establishment of Roman Greece, sought to reproduce the marble and bronze artworks of the Classical and Hellenistic periods. They did so by creating molds of original sculptures, producing plaster casts that could be sent to any sculptor's workshop of the Mediterranean where these works of art could be duplicated. These were often faithful reproductions of originals, yet other times they fused several elements of various artworks into one group, or simply added Roman portraiture heads to preexisting athletic Greek bodies.[53]

The Dying Gaul, a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic work of the late third century BC Capitoline Museums, Rome.

The Dying Gaul, a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic work of the late third century BC Capitoline Museums, Rome.- Roman copy of an original Hellenistic bust depicting Seleucus I Nicator (founder of the Seleucid Empire), found in Herculaneum, Italy

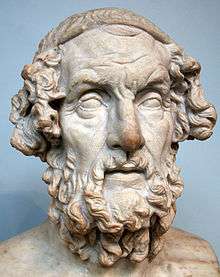

A Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original (2nd century BC) depicting Homer, from Baiae, Italy, British Museum

A Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original (2nd century BC) depicting Homer, from Baiae, Italy, British Museum Statue of Mars from the Forum of Nerva, 2nd century AD, based on an Augustan-era original that in turn used a Hellenistic Greek model of the 4th century BC, Capitoline Museums[54]

Statue of Mars from the Forum of Nerva, 2nd century AD, based on an Augustan-era original that in turn used a Hellenistic Greek model of the 4th century BC, Capitoline Museums[54] Drunken old woman clutching a lagynos. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original of the 2nd century BC, credited to Myron.

Drunken old woman clutching a lagynos. Marble, Roman copy after a Greek original of the 2nd century BC, credited to Myron. Roman bronze reduction of Myron's Discobolos, 2nd century AD

Roman bronze reduction of Myron's Discobolos, 2nd century AD_-_Lateral_View.jpg) The Boxer of Quirinal, a Hellenistic sculpture in the National Museum of Rome.

The Boxer of Quirinal, a Hellenistic sculpture in the National Museum of Rome. Child playing with a goose. Roman copy (1st–2nd centuries AD) of a Greek original, in the Louvre.

Child playing with a goose. Roman copy (1st–2nd centuries AD) of a Greek original, in the Louvre. Head of an old woman, Roman copy after a Hellenistic original of the 3rd or 2nd century BC.

Head of an old woman, Roman copy after a Hellenistic original of the 3rd or 2nd century BC. The Tyche of Antioch. Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Eutychides of the 3rd century BC.

The Tyche of Antioch. Roman copy after a Greek bronze original by Eutychides of the 3rd century BC.- Old market woman, Roman artwork after a Hellenistic original of the 2nd century BC.

Demosthenes. Marble, Roman copy after an original by Polyeuktos (ca. 280).

Demosthenes. Marble, Roman copy after an original by Polyeuktos (ca. 280). Crouching Aphrodite, marble copy from the 1st century BC after a Hellenistic original of the 3rd century BC.

Crouching Aphrodite, marble copy from the 1st century BC after a Hellenistic original of the 3rd century BC. Artemis of the Rospigliosi type. Marble, Roman artwork of the Imperial Era, 1st–2nd centuries AD. Copy of a Greek original, Louvre

Artemis of the Rospigliosi type. Marble, Roman artwork of the Imperial Era, 1st–2nd centuries AD. Copy of a Greek original, Louvre.jpg) Roman marble copy of Boy with Thorn, c.25 - 50 CE,

Roman marble copy of Boy with Thorn, c.25 - 50 CE,- The Farnese Hercules, probably an enlarged copy made in the early 3rd century AD and signed by a certain Glykon, from an original by Lysippos (or one of his circle) that would have been made in the 4th century BC; the copy was made for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (dedicated in 216 AD), where it was recovered in 1546

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Greek art |

|---|

|

| Greek Bronze Age |

| Ancient Greece |

| Medieval Greece |

| Post-Byzantine Greece |

| Modern Greece |

| Ancient art history |

|---|

| Middle East |

| Asia |

| European prehistory |

| Classical art |

- Alexander the Great

- Hellenistic civilization

- Hellenistic Greece

- Hellenistic period

- Art in ancient Greece

- Pottery of Ancient Greece

- Ancient Greek vase painting

- Greek sculpture

- Hellenistic influence on Indian art

- Parthian art

- Bacchic art

References and sources

- References

- 1 2 Pedley, p. 339

- ↑ Burn, p. 16

- ↑ Pollitt, p. 22

- ↑ Winter, p. 42

- ↑ Anderson, p. 161

- 1 2 Havelock, p. ?

- ↑ Pedley, p. 348

- ↑ Burn, p. 92

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXIV, 52)

- 1 2 Richter, p. 233

- ↑ Smith, 33–40, 136–140

- ↑ Paul Lawrence. "The Classical Nude". p. 5.

- ↑ Smith, 127–154

- ↑ Green, pp. 39-40

- ↑ Boardman, p. 179

- ↑ "Studies in the History of Art". National Gallery of Art. 1 January 1999 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Winter, p. 235

- ↑ Paul Lawrence. "The Classical Nude". p. 4.

- ↑ Pollitt, p. 110

- ↑ Richter, p. 234

- ↑ Singleton, p. 165

- ↑ "Scientific American". Munn & Company. 1 January 1905 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Burn, p. 160

- 1 2 3 Pedley, p. 371

- ↑ Lessing contra Winckelmann

- ↑ Richter, p. 237

- ↑ Smith, 240–241

- ↑ Smith, 258-261

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/haht/hd_haht.htm

- 1 2 Pedley, p. 377

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya (21 August 2010). "Discovery of ancient cave paintings in Petra stuns art scholars". The Observer. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ Pollitt, p. 40

- ↑ Bruno, p. 1

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXV, 110)

- ↑ Kleiner, p. 142

- ↑ Mosaics of the Greek and Roman world By Katherine M. D. Dunbabin pg. 14

- ↑ Chugg, Andrew (2006). Alexander's Lovers. Raleigh, N.C.: Lulu. ISBN 978-1-4116-9960-1, pp 78-79.

- 1 2 Kleiner and Gardner, pg. 135

- ↑ http://www.thejoyofshards.co.uk/history/index.shtml

- 1 2 3 Kleiner and Gardner, pg. 136

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History (XXXVI, 184)

- ↑ "Asarotos oikos: The unswept room".

- ↑ Pedley, p. 382

- ↑ Burn, p. 117

- ↑ Pedley, p. 385

- ↑ Von Bothner, Dietrich, Greek vase painting, p. 67, 1987, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.)

- ↑ Masseglia, p. 140

- ↑ Three Centuries of Hellenistic Terracottas

- ↑ Burn, p. 30

- ↑ Honour, p. 192

- ↑ Pollitt, p. 24

- ↑ "Hellenistic Coin Portraits".

- ↑ Department of Greek and Roman Art (October 2002). "Roman Copies of Greek Statues." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Capitoline Museums. "Colossal statue of Mars Ultor also known as Pyrrhus - Inv. Scu 58." Capitolini.info. Accessed 8 October 2016.

- Sources

- This article draws heavily on the fr:Art hellénistique article in the French-language Wikipedia, which was accessed in the version of 10 November 2006.

- Anderson, William J. The Architecture of Ancient Greece. London: Harrison, Jehring, & Co. ISBN 0404147259.

- Boardman, John (1989). Greek Art. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20292-3.

- Bruno, Vincent L. Hellenistic Painting Techniques: The Evidence of the Delos Fragments.

- Burn, Lucilla (2005). Hellenistic Art: From Alexander The Great To Augustus. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust Publications. ISBN 0-89236-776-8.

- Charbonneaux, Jean, Jean Martin and Roland Villard (1973). Hellenistic Greece. Peter Green (trans.). New York: Braziller. ISBN 0-8076-0666-9.

- Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. ISBN 0520083490.

- Havelock, Christine Mitchell (1968). Hellenistic Art. Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society Ltd. ISBN 0-393-95133-2.

- Holtzmann, Bernard and Alain Pasquier (2002). Histoire de l'art antique: l'art grec. Réunion des musées nationaux. ISBN 2-7118-3782-3.

- Honour, Hugh. A World History of Art. ISBN 1856694518.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2008). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History. Cengage Learning. ISBN 0-495-11549-5.

- Masseglia, Jane. Body Language in Hellenistic Art and Society. ISBN 0198723598.

- Pedley, John Griffiths. Greek Art and Archaeology. ISBN 0-205-00133-5.

- Pollitt, Jerome J. (1986). Art in the Hellenistic Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27672-1.

- Richter, Gisela M. A. (1970). The Sculpture and Sculptors of the Greeks.

- Singleton, Esther. Famous sculpture as seen and described by great writers.

- Stewart, Andrew (2014). Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1-107-62592-0.

- Winter, Frederick. Studies in Hellenistic Architecture. ISBN 0802039146.

- Zanker, Graham (2004). Modes of Viewing in Hellenistic Poetry and Art. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299194507.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hellenistic art. |

- Selection of Hellenistic works at the British Museum

- Selection of Hellenistic works at the Louvre

- Hellenistic Art, Insecula.com