Seleucid Empire

| Seleucid Empire | ||||||||||||||||||

| Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The empire at its greatest extent and on the eve of the death of Seleucus I, 281 BC | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Seleucia (305–240 BC) Antioch (240–63 BC) | |||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Greek (official)[5] Persian Aramaic[5] | |||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Olympianism Babylonian religion[6] Zoroastrianism | |||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||||||

| Basileus | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | 305–281 BC | Seleucus I (first) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 65–63 BC | Philip II (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Hellenistic period | |||||||||||||||||

| • | Wars of the Diadochi | 312 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Battle of Ipsus | 301 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Roman–Seleucid War | 192–188 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Treaty of Apamea | 188 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Maccabean Revolt | 167–160 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| • | Annexed by Rome | 63 BC | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||

| • | 303 BC[7] | 3,000,000 km² (1,158,306 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 301 BC[7] | 3,900,000 km² (1,505,798 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 270 BC[7] | 3,200,000 km² (1,235,527 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 240 BC[7] | 2,600,000 km² (1,003,866 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 175 BC[7] | 800,000 km² (308,882 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | ||||||||||||||||||

The Seleucid Empire (/sɪˈljuːsɪd/;[8] Ancient Greek: Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, Basileía tōn Seleukidōn) was a Hellenistic state ruled by the Seleucid dynasty, which existed from 312 BC to 63 BC; it was founded by Seleucus I Nicator following the division of the Macedonian empire vastly expanded by Alexander the Great.[9][10][11][12] Seleucus received Babylonia and, from there, expanded his dominions to include much of Alexander's near eastern territories. At the height of its power, it included central Anatolia, Persia, the Levant, Mesopotamia, and what is now Kuwait, Afghanistan, and parts of Pakistan and Turkmenistan.

The Seleucid Empire was a major center of Hellenistic culture that maintained the preeminence of Greek customs where a Greek political elite dominated, mostly in the urban areas.[12][13][14][15] The Greek population of the cities who formed the dominant elite were reinforced by immigration from Greece.[12][13] Seleucid expansion into Anatolia and Greece was abruptly halted after decisive defeats at the hands of the Roman army. Their attempts to defeat their old enemy Ptolemaic Egypt were frustrated by Roman demands. Having come into conflict with Chandragupta Maurya of the Maurya Empire, after several defeats, Seleucus entered into an agreement with Maurya where he ceded vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan and offered his daughter for marriage to the Emperor to formalize the alliance. Much of the eastern part of the empire was conquered by the Parthians under Mithridates I of Parthia in the mid-2nd century BC, yet the Seleucid kings continued to rule a rump state from Syria until the invasion by Armenian king Tigranes the Great and their ultimate overthrow by the Roman general Pompey.

Starting from the 2nd century BC, ancient writers referred to the Seleucid ruler as the King of Syria, Lord of Asia, and other designations;[16] the evidence for the Seleucid rulers representing themselves as kings of Syria is provided by the inscription of a certain Antigonus son of Menophilus, who described himself as the "admiral of Alexander, king of Syria".[17]

History

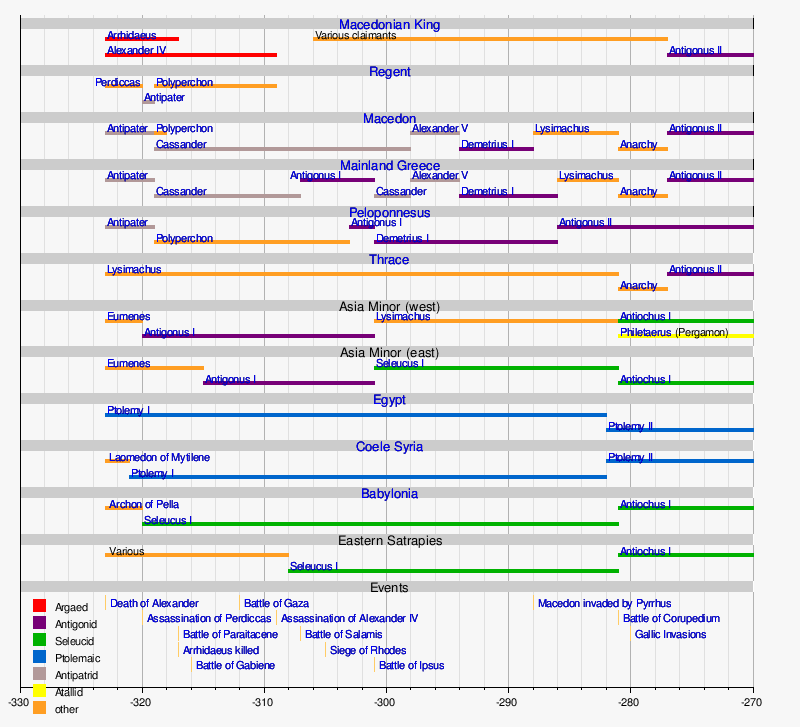

Partition of Alexander's empire

Alexander, who quickly conquered the Persian Empire under its last Achaemenid dynast, Darius III, died young in 323 BC, leaving an expansive empire of partly Hellenised culture without an adult heir. The empire was put under the authority of a regent in the person of Perdiccas, and the territories were divided between Alexander's generals, who thereby became satraps, at the Partition of Babylon, all in that same year.

Rise of Seleucus

Alexander's generals (the Diadochi) jostled for supremacy over parts of his empire. Ptolemy, a former general and the satrap of Egypt, was the first to challenge the new system; this led to the demise of Perdiccas. Ptolemy's revolt led to a new subdivision of the empire with the Partition of Triparadisus in 320 BC. Seleucus, who had been "Commander-in-Chief of the Companion cavalry" (hetairoi) and appointed first or court chiliarch (which made him the senior officer in the Royal Army after the regent and commander-in-chief Perdiccas since 323 BC, though he helped to assassinate him later) received Babylonia and, from that point, continued to expand his dominions ruthlessly. Seleucus established himself in Babylon in 312 BC, the year used as the foundation date of the Seleucid Empire. He ruled not only Babylonia, but the entire enormous eastern part of Alexander's empire, as described by Appian:

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.[18]

Seleucus went as far as India, where, after two years of war, he reached an agreement with Chandragupta Maurya, in which he exchanged his eastern territories for a considerable force of 500 war elephants, which would play a decisive role at Ipsus (301 BC). Strabo, in his Geographica, wrote:

The Indians occupy [in part] some of the countries situated along the Indus, which formerly belonged to the Persians: Alexander deprived the Ariani of them, and established there settlements of his own. But Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta Maurya) in consequence of a marriage contract, and received in return five hundred elephants.[19]

Westward expansion

Following his and Lysimachus' victory over Antigonus Monophthalmus at the decisive Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC, Seleucus took control over eastern Anatolia and northern Syria.

In the latter area, he founded a new capital at Antioch on the Orontes, a city he named after his father. An alternative capital was established at Seleucia on the Tigris, north of Babylon. Seleucus's empire reached its greatest extent following his defeat of his erstwhile ally, Lysimachus, at Corupedion in 281 BC, after which Seleucus expanded his control to encompass western Anatolia. He hoped further to take control of Lysimachus's lands in Europe – primarily Thrace and even Macedonia itself, but was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus on landing in Europe.

His son and successor, Antiochus I Soter, was left with an enormous realm consisting of nearly all of the Asian portions of the Empire, but faced with Antigonus II Gonatas in Macedonia and Ptolemy II Philadelphus in Egypt, he proved unable to pick up where his father had left off in conquering the European portions of Alexander's empire.

An overextended domain

Nevertheless, even before Seleucus' death, it was difficult to assert control over the vast eastern domains of the Seleucids. Seleucus invaded the Punjab region of India in 305 BC, confronting Chandragupta Maurya (Sandrokottos), founder of the Maurya Empire. It is said that Chandragupta fielded an army of 600,000 men and 9,000 war elephants.[20]

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory, sealed in a treaty, west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[21][22] Archaeologically, concrete indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandahar in southern Afghanistan. According to Appian:

He [Seleucus] crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship."[23]

It is generally thought that Chandragupta married Seleucus's daughter, or a Macedonian princess, a gift from Seleucus to formalize an alliance. In a return gesture, Chandragupta sent 500 war-elephants,[24][25][26][27][28] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar state). Megasthenes wrote detailed descriptions of India and Chandragupta's reign, which have been partly preserved to us through Diodorus Siculus. Later Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka the Great, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[29]

Other territories lost before Seleucus' death were Gedrosia in the south-east of the Iranian plateau, and, to the north of this, Arachosia on the west bank of the Indus River.

Antiochus I (reigned 281–261 BC) and his son and successor Antiochus II Theos (reigned 261–246 BC) were faced with challenges in the west, including repeated wars with Ptolemy II and a Celtic invasion of Asia Minor—distracting attention from holding the eastern portions of the Empire together. Towards the end of Antiochus II's reign, various provinces simultaneously asserted their independence, such as Bactria and Sogdiana under Diodotus, Cappadocia under Ariarathes III, and Parthia under Andragoras. A few years later, the latter was defeated and killed by the invading Parni of Arsaces - the region would then become the core of the Parthian Empire.

Diodotus, governor for the Bactrian territory, asserted independence in around 245 BC, although the exact date is far from certain, to form the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. This kingdom was characterized by a rich Hellenistic culture and was to continue its domination of Bactria until around 125 BC when it was overrun by the invasion of northern nomads. One of the Greco-Bactrian kings, Demetrius I of Bactria, invaded India around 180 BC to form the Greco-Indian kingdom, lasting until around AD 20.

The Seleucid satrap of Parthia, named Andragoras, first claimed independence, in a parallel to the secession of his Bactrian neighbour. Soon after, however, a Parthian tribal chief called Arsaces invaded the Parthian territory around 238 BC to form the Arsacid Dynasty, from which the Parthian Empire originated.

Antiochus II's son Seleucus II Callinicus came to the throne around 246 BC. Seleucus II was soon dramatically defeated in the Third Syrian War against Ptolemy III of Egypt and then had to fight a civil war against his own brother Antiochus Hierax. Taking advantage of this distraction, Bactria and Parthia seceded from the empire. In Asia Minor too, the Seleucid dynasty seemed to be losing control: the Gauls had fully established themselves in Galatia, semi-independent semi-Hellenized kingdoms had sprung up in Bithynia, Pontus, and Cappadocia, and the city of Pergamum in the west was asserting its independence under the Attalid Dynasty. Seleucid economy started to show the first signs of weakness, as Galatians gained independence and Pergamum took control of coastal cities in Anatolia. Consequentially, they managed to partially block contact with the West.[30]

Revival (223–191 BC)

A revival would begin when Seleucus II's younger son, Antiochus III the Great, took the throne in 223 BC. Although initially unsuccessful in the Fourth Syrian War against Egypt, which led to a defeat at the Battle of Raphia (217 BC), Antiochus would prove himself to be the greatest of the Seleucid rulers after Seleucus I himself. He spent the next ten years on his anabasis through the eastern parts of his domain and restoring rebellious vassals like Parthia and Greco-Bactria to at least nominal obedience. He won the Battle of the Arius and besieged the Bactrian capital, and even emulated Alexander with an expedition into India where he met with king Sophagasenus receiving war elephants:

"He (Antiochus) crossed the Caucasus and descended into India; renewed his friendship with Sophagasenus the king of the Indians; received more elephants, until he had a hundred and fifty altogether; and having once more provisioned his troops, set out again personally with his army: leaving Androsthenes of Cyzicus the duty of taking home the treasure which this king had agreed to hand over to him". Polybius 11.39

When he returned to the west in 205 BC, Antiochus found that with the death of Ptolemy IV, the situation now looked propitious for another western campaign. Antiochus and Philip V of Macedon then made a pact to divide the Ptolemaic possessions outside of Egypt, and in the Fifth Syrian War, the Seleucids ousted Ptolemy V from control of Coele-Syria. The Battle of Panium (198 BC) definitively transferred these holdings from the Ptolemies to the Seleucids. Antiochus appeared, at the least, to have restored the Seleucid Kingdom to glory.

Expansion into Greece and war with Rome

Following the defeat of his erstwhile ally Philip by Rome in 197 BC, Antiochus saw the opportunity for expansion into Greece itself. Encouraged by the exiled Carthaginian general Hannibal, and making an alliance with the disgruntled Aetolian League, Antiochus launched an invasion across the Hellespont. With his huge army he aimed to establish the Seleucid empire as the foremost power in the Hellenic world, but these plans put the empire on a collision course with the new rising power of the Mediterranean, the Roman Republic. At the battles of Thermopylae (191 BC) and Magnesia (190 BC), Antiochus's forces suffered resounding defeats, and he was compelled to make peace and sign the Treaty of Apamea (188 BC), the main clause of which saw the Seleucids agree to pay a large indemnity, to retreat from Anatolia and to never again attempt to expand Seleucid territory west of the Taurus Mountains. The Kingdom of Pergamum and the Republic of Rhodes, Rome's allies in the war, gained the former Seleucid lands in Anatolia. Antiochus died in 187 BC on another expedition to the east, where he sought to extract money to pay the indemnity.

Roman power, Parthia and Judea

The reign of his son and successor Seleucus IV Philopator (187-175 BC) was largely spent in attempts to pay the large indemnity, and Seleucus was ultimately assassinated by his minister Heliodorus.

Seleucus' younger brother, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, now seized the throne. He attempted to restore Seleucid power and prestige with a successful war against the old enemy, Ptolemaic Egypt, which met with initial success as the Seleucids defeated and drove the Egyptian army back to Alexandria itself. As the king planned on how to conclude the war, he was informed that Roman commissioners, led by the Proconsul Gaius Popillius Laenas, were near and requesting a meeting with the Seleucid king. Antiochus agreed, but when they met and Antiochus held out his hand in friendship, Popilius placed in his hand the tablets on which was written the decree of the senate and told him to read it. When the king said that he would call his friends into council and consider what he ought to do, Popilius drew a circle in the sand around the king's feet with the stick he was carrying and said, "Before you step out of that circle give me a reply to lay before the senate." For a few moments he hesitated, astounded at such a peremptory order, and at last replied, "I will do what the senate thinks right." He then chose to withdraw rather than set the empire to war with Rome again.[31]

The latter part of his reign saw a further disintegration of the Empire despite his best efforts. Weakened economically, militarily and by loss of prestige, the Empire became vulnerable to rebels in the eastern areas of the empire, who began to further undermine the empire while the Parthians moved into the power vacuum to take over the old Persian lands. Antiochus' aggressive Hellenizing (or de-Judaizing) activities provoked a full scale armed rebellion in Judea—the Maccabean Revolt.[32] Efforts to deal with both the Parthians and the Jews as well as retain control of the provinces at the same time proved beyond the weakened empire's power. Antiochus died during a military expedition against the Parthians in 164 BC.

Civil war and further decay

After the death of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly unstable. Frequent civil wars made central authority tenuous at best. Epiphanes' young son, Antiochus V Eupator, was first overthrown by Seleucus IV's son, Demetrius I Soter in 161 BC. Demetrius I attempted to restore Seleucid power in Judea particularly, but was overthrown in 150 BC by Alexander Balas – an impostor who (with Egyptian backing) claimed to be the son of Epiphanes. Alexander Balas reigned until 145 BC when he was overthrown by Demetrius I's son, Demetrius II Nicator. Demetrius II proved unable to control the whole of the kingdom, however. While he ruled Babylonia and eastern Syria from Damascus, the remnants of Balas' supporters – first supporting Balas' son Antiochus VI, then the usurping general Diodotus Tryphon – held out in Antioch.

Meanwhile, the decay of the Empire's territorial possessions continued apace. By 143 BC, the Jews in the form of the Maccabees had fully established their independence. Parthian expansion continued as well. In 139 BC, Demetrius II was defeated in battle by the Parthians and was captured. By this time, the entire Iranian Plateau had been lost to Parthian control.

Demetrius Nicator's brother, Antiochus VII Sidetes, took the throne after his brother's capture. He faced the enormous task of restoring a rapidly crumbling empire, one facing threats on multiple fronts. Hard-won control of Coele-Syria was threatened by the Jewish Maccabee rebels. Once-vassal dynasties in Armenia, Cappadocia, and Pontus were threatening Syria and northern Mesopotamia; the nomadic Parthians, brilliantly led by Mithridates I of Parthia, had overrun upland Media (home of the famed Nisean horse herd); and Roman intervention was an ever-present threat. Sidetes managed to bring the Maccabees to heel and frighten the Anatolian dynasts into a temporary submission; then, in 133, he turned east with the full might of the Royal Army (supported by a body of Jews under the Maccabee prince, John Hyrcanus) to drive back the Parthians.

Sidetes' campaign initially met with spectacular success, recapturing Mesopotamia, Babylonia, and Media and defeating and slaying the Parthian Satrap of Seleucia-on-Tigris in personal combat. In the winter of 130/129 BC, his army was scattered in winter quarters throughout Media and Persis when the Parthian king, Phraates II, counter-attacked. Moving to intercept the Parthians with only the troops at his immediate disposal, he was ambushed and killed. Antiochus Sidetes is sometimes called the last great Seleucid king.

After the death of Antiochus VII Sidetes, all of the recovered eastern territories were recaptured by the Parthians. The Maccabees again rebelled, civil war soon tore the empire to pieces, and the Armenians began to encroach on Syria from the north.

Collapse (100–63 BC)

By 100 BC, the once formidable Seleucid Empire encompassed little more than Antioch and some Syrian cities. Despite the clear collapse of their power, and the decline of their kingdom around them, nobles continued to play kingmakers on a regular basis, with occasional intervention from Ptolemaic Egypt and other outside powers. The Seleucids existed solely because no other nation wished to absorb them – seeing as they constituted a useful buffer between their other neighbours. In the wars in Anatolia between Mithridates VI of Pontus and Sulla of Rome, the Seleucids were largely left alone by both major combatants.

Mithridates' ambitious son-in-law, Tigranes the Great, king of Armenia, however, saw opportunity for expansion in the constant civil strife to the south. In 83 BC, at the invitation of one of the factions in the interminable civil wars, he invaded Syria and soon established himself as ruler of Syria, putting the Seleucid Empire virtually at an end.

Seleucid rule was not entirely over, however. Following the Roman general Lucullus' defeat of both Mithridates and Tigranes in 69 BC, a rump Seleucid kingdom was restored under Antiochus XIII. Even so, civil wars could not be prevented, as another Seleucid, Philip II, contested rule with Antiochus. After the Roman conquest of Pontus, the Romans became increasingly alarmed at the constant source of instability in Syria under the Seleucids. Once Mithridates was defeated by Pompey in 63 BC, Pompey set about the task of remaking the Hellenistic East, by creating new client kingdoms and establishing provinces. While client nations like Armenia and Judea were allowed to continue with some degree of autonomy under local kings, Pompey saw the Seleucids as too troublesome to continue; doing away with both rival Seleucid princes, he made Syria into a Roman province.

Culture

The Seleucid empire's geographical span, from the Aegean Sea to what is now Afghanistan and Pakistan, created a melting pot of various peoples, such as Greeks, Armenians, Persians, Medes, Assyrians and Jews. The immense size of the empire, followed by its encompassing nature, encouraged the Seleucid rulers to implement a policy of ethnic unity—a policy initiated by Alexander.

The Hellenization of the Seleucid empire was achieved by the establishment of Greek cities throughout the empire. Historically significant towns and cities, such as Antioch, were created or renamed with more appropriate Greek names. The creation of new Greek cities and towns was aided by the fact that the Greek mainland was overpopulated and therefore made the vast Seleucid empire ripe for colonization. Colonization was used to further Greek interest while facilitating the assimilation of many native groups. Socially, this led to the adoption of Greek practices and customs by the educated native classes in order to further themselves in public life, and at the same time the ruling Macedonian class gradually adopted some of the local traditions. By 313 BC, Hellenic ideas had begun their almost 250-year expansion into the Near East, Middle East, and Central Asian cultures. It was the empire's governmental framework to rule by establishing hundreds of cities for trade and occupational purposes. Many of the existing cities began—or were compelled by force—to adopt Hellenized philosophic thought, religious sentiments, and politics although the Seleucid rulers did incorporate Babylonian religious tenets to gain support.[34]

Synthesizing Hellenic and indigenous cultural, religious, and philosophical ideas met with varying degrees of success—resulting in times of simultaneous peace and rebellion in various parts of the empire. Such was the case with the Jewish population of the Seleucid empire; the Jews' refusal to willingly Hellenize their religious beliefs or customs posed a significant problem which eventually led to war. Contrary to the accepting nature of the Ptolemaic empire towards native religions and customs, the Seleucids gradually tried to force Hellenization upon the Jewish people in their territory by outlawing Judaism. This eventually led to the revolt of the Jews under Seleucid control, which would later lead to the Jews achieving independence from the Seleucid empire.

List of Seleucid rulers

See also

- Seleucid army

- Hellenistic period

- Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

- Hasmonean Dynasty

- Indo-Greek Kingdom

- Parthian Empire

References

- ↑ Cohen, Getzel M; The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa, pp. 13.

- ↑ Lynette G. Mitchell; Every Inch a King: Comparative Studies on Kings and Kingship in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds, page 123.

- ↑ Cohen, Getzel M; The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa, pp. 13.

- ↑ Lynette G. Mitchell; Every Inch a King: Comparative Studies on Kings and Kingship in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds, page 123.

- 1 2 Richard N. Frye, The History of Ancient Iran, (Ballantyne Ltd, 1984), 164.

- ↑ Julye Bidmead, The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia, (Gorgias Press, 2004), 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 121. doi:10.2307/1170959. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, 1st ed. "Seleucid, n. and adj." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1911.

- ↑ Jones, Kenneth Raymond (2006). Provincial reactions to Roman imperialism: the aftermath of the Jewish revolt, A.D. 66-70, Parts 66-70. University of California, Berkeley. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-542-82473-9.

... and the Greeks, or at least the Greco-Macedonian Seleucid Empire, replace the Persians as the Easterners.

- ↑ Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (London, England) (1993). The Journal of Hellenic studies, Volumes 113-114. Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. p. 211.

The Seleucid kingdom has traditionally been regarded as basically a Greco-Macedonian state and its rulers thought of as successors to Alexander.

- ↑ Baskin, Judith R.; Seeskin, Kenneth (2010). The Cambridge Guide to Jewish History, Religion, and Culture. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-68974-8.

The wars between the two most prominent Greek dynasties, the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria, unalterably change the history of the land of Israel…As a result the land of Israel became part of the empire of the Syrian Greek Seleucids.

- 1 2 3 Glubb, John Bagot (1967). Syria, Lebanon, Jordan. Thames & Hudson. p. 34. OCLC 585939.

In addition to the court and the army, Syrian cities were full of Greek businessmen, many of them pure Greeks from Greece. The senior posts in the civil service were also held by Greeks. Although the Ptolemies and the Seleucids were perpetual rivals, both dynasties were Greek and ruled by means of Greek officials and Greek soldiers. Both governments made great efforts to attract immigrants from Greece, thereby adding yet another racial element to the population.

- 1 2 Steven C. Hause; William S. Maltby (2004). Western civilization: a history of European society. Thomson Wadsworth. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-534-62164-3.

The Greco-Macedonian Elite. The Seleucids respected the cultural and religious sensibilities of their subjects but preferred to rely on Greek or Macedonian soldiers and administrators for the day-to-day business of governing. The Greek population of the cities, reinforced until the second century BCE by immigration from Greece, formed a dominant, although not especially cohesive, elite.

- ↑ Victor, Royce M. (2010). Colonial education and class formation in early Judaism: a postcolonial reading. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-567-24719-3.

Like other Hellenistic kings, the Seleucids ruled with the help of their "friends" and a Greco-Macedonian elite class separate from the native populations whom they governed.

- ↑ Britannica, Seleucid kingdom, 2008, O.Ed.

- ↑ Nigel Wilson (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. p. 652.

- ↑ Paul J. Kosmin (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings. p. 112.

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55

- ↑ Strabo 15.2.1(9)

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History VI, 22.4

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1972). Aśoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Clark, Walter Eugene (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology". Classical Philology. 14 (4): 297–313. doi:10.1086/360246.

- ↑ Appian, History of Rome, "The Syrian Wars" 55

- ↑ Ancient India, (Kachroo ,p.196)

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India, (Hunter,p.167)

- ↑ The evolution of man and society, (Darlington ,p.223)

- ↑ Tarn, W. W. (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 60: 84–94. doi:10.2307/626263. JSTOR 626263.

- ↑ Partha Sarathi Bose (2003). Alexander the Great's Art of Strategy. Gotham Books. ISBN 1-59240-053-1.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", Chap. 21

- ↑ Castrén, Paavo (2011). Uusi antiikin historia (in Finnish). Otava. p. 244. ISBN 978-951-1-21594-3.

- ↑ "Livy's History of Rome". mu.edu.

- ↑ Chanukah, Shabbat 21b, Babylonian Talmud

- ↑ "History of Iran: Seleucid Empire". iranchamber.com.

- ↑ Julye Bidmead, The Akitu Festival: Religious Continuity and Royal Legitimation in Mesopotamia, 143.

Further reading

- G. G. Aperghis, The Seleukid Royal Economy. The Finances and Financial Administration of the Seleukid Empire, Cambridge, 2004.

- Laurent Capdetrey, Le pouvoir séleucide. Territoire, administration, finances d'un royaume hellénistique (312-129 avant J.C.). (Collection "Histoire"). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2007.

- A. Houghton, C. Lorber, Seleucid Coins. A Comprehensive Catalogue, Part I, Seleucus I through Antiochus III, With Metrological Tables by B. Kritt, I-II, New York - Lancaster - London, 2002.

- Paul J. Kosmin, The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- Michael J. Taylor, Antiochus the Great (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2013).

External links

- Livius, The Seleucid Empire by Jona Lendering

- Genealogy of the Seleucids

- Seleukid Bibliography maintained at the History Department of Utrecht University

- The Empire on Facebook

- Seleucid Research Bibliography, compiled and maintained by the Seleucid Study Group