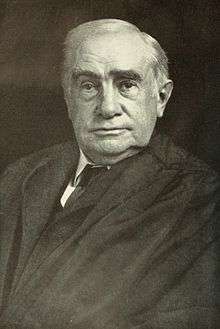

Henry Billings Brown

| Henry Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office December 29, 1890 – May 28, 1906[1] | |

| Nominated by | Benjamin Harrison |

| Preceded by | Samuel Miller |

| Succeeded by | William Moody |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan | |

|

In office March 19, 1875 – December 29, 1890 | |

| Nominated by | Ulysses Grant |

| Preceded by | John Longyear |

| Succeeded by | Henry Swan |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 2, 1836 Lee, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

September 4, 1913 (aged 77) Bronxville, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Caroline Pitts (1864–1901) Josephine Tyler (1904–1913) |

| Alma mater |

Yale University Harvard University |

| Religion | Congregationalism |

Henry Billings Brown (March 2, 1836 – September 4, 1913) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from December 29, 1890 to May 28, 1906. An admiralty lawyer and U.S. District Judge in Detroit before ascending to the high court, Brown authored hundreds of opinions in his 31 years as a federal judge, including the majority opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld the legality of racial segregation in public transportation.

Early career

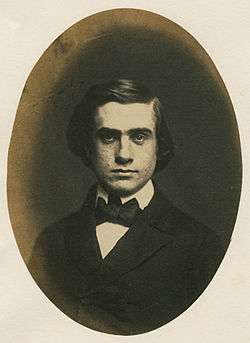

Family and education

Brown was born in South Lee, Massachusetts, and grew up in Massachusetts and Connecticut. His was a New England merchant family. Brown entered Yale College at 16, where he was a member of Alpha Delta Phi fraternity. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree there in 1856. Among his undergraduate classmates were Chauncey Depew, later a U.S. Senator from New York, and David Josiah Brewer, who became Brown's colleague on the Supreme Court. Depew roomed across the hall from Brown for three years in Old North Middle Hall, and remembered "a feminine quality [about Brown] which led to his being called Henrietta, though there never was a more robust, courageous and decided man in meeting the problems of life[.]"[2] After a yearlong tour of Europe, Brown attended a term of legal education at Yale Law School and another at Harvard Law School. Many lawyers at the time did not earn law degrees, and he did not.

Legal activities in Detroit

Admitted to the Michigan Bar in 1860, Brown's early law practice was in Detroit, Michigan, where he specialized in admiralty law (that is, shipping law on the Great Lakes). In addition to his private law practice, at times between 1861 and 1868 Brown served as Deputy U.S. Marshall, assistant United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, and judge of the Wayne County Circuit Court in Detroit.[3]

Personal life

In 1864, Brown married Caroline Pitts, the daughter of a wealthy Michigan lumber merchant. They had no children. He did not serve in the Union Army during the Civil War, but like many well-to-do men instead hired a substitute soldier to take his place.

Brown kept diaries from his college days until his appointment as a federal judge in 1875. Now held in the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library, they suggest that he was both genial and ambitious, but also depressed and doubtful about himself.

U.S. District Judge

Appointment

The death of Brown's father-in-law left Brown and his wife financially independent; he was willing to accept the relatively low salary of a federal judge. On March 17, 1875, Brown was nominated by President Ulysses Grant to a seat on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan left vacant by the death of John Wesley Longyear. Brown was confirmed by the United States Senate two days later and immediately received his commission.

Publishing and teaching

Brown edited a collection of rulings and orders in important admiralty cases from inland waters,[4] and later compiled a case book on admiralty law for lectures at Georgetown University.[5] He also taught admiralty law classes at the University of Michigan Law School from 1860 to 1875, and medical jurisprudence at the Detroit Medical College (now the medical school of Wayne State University) from 1868 to 1871.[6]

Supreme Court

Appointment

After lobbying by Brown and by the Michigan congressional delegation, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Brown, a Republican, to the Supreme Court of the United States on December 23, 1890, to a seat vacated by Samuel F. Miller. Brown was unanimously confirmed by the Senate on December 29, 1890, and received his commission the same day. In an autobiographical essay, Brown commented "While I had been much attached to Detroit and its people, there was much to compensate me in my new sphere of activity. If the duties of the new office were not so congenial to my taste as those of district judge, it was a position of far more dignity, was better paid and was infinitely more gratifying to one's ambition."[7]

Jurisprudence

As a jurist, Brown was generally against government intervention in business, and concurred with the majority opinion in Lochner v. New York (1905) striking down a limitation on maximum working hours. He did, however, support the federal income tax in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895), and wrote for the Court in Holden v. Hardy (1898), upholding a Utah law restricting male miners to an eight-hour day.

.jpg)

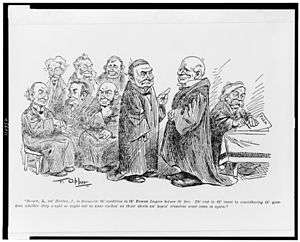

Plessy v. Ferguson

Brown is known for the 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, in which he wrote the majority opinion upholding the principle and legitimacy of "separate but equal" facilities for American blacks and whites. In his opinion, Brown argued that the recognition of racial difference did not necessarily violate Constitutional principle. As long as equal facilities and services were available to all citizens, the "commingling of the two races" need not be enforced.[8] Plessy, which provided legal support for the system of Jim Crow Laws, was overruled by the Court in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. When issued, Plessy attracted relatively little attention, but in the late 20th century it came to be vilified, and Brown along with it.

Insular Cases

Justice Brown authored the Court's 1901 opinion in DeLima v. Bidwell, one of the Insular Cases, considering the status of territories acquired by the U.S. in the Spanish–American War of 1898.

Hale v. Henkel

Brown adroitly expounded for the majority the powers accorded to the grand jury in Hale v. Henkel, a 1906 case where the defendant—a tobacco company executive—refused to testify to the grand jury on several grounds in a case founded upon the Sherman Antitrust Act. This judgement, which can be considered his valedictory address, was rendered 12 March 1906, a scant 10 weeks prior to his retirement.

Personal life in Washington, D.C.

In 1891, he paid $25,000 (equivalent to $660,000 in 2015) to the Riggs family[9] for land at 1720 16th Street, NW, in Washington, D.C., hired architect William Henry Miller, and built a five-story, 18-room mansion for $40,000 (equivalent to $1,055,000 in 2015).[10] He would live in this house, later known as the Toutorsky Mansion, until his death. Ironically—in light of Brown's racial attitudes—the house is now the embassy of the Republic of the Congo. Brown's wife Caroline died in 1901. Three years later, Brown married a close friend of hers, the widow Josephine E. Tyler, who survived him.

Retirement

..jpg)

Near the end of his years on the Court, Brown largely lost his eyesight. He retired from the Court on May 28, 1906 at the age of 70.

Death

Brown died of heart disease on September 4, 1913, at a hotel in Bronxville, New York. He is buried next to his first wife in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

Legacy

Abilities

Brown has been remembered as "a capable and solid, if unimaginative, legal technician."[11] One of his friends offered the faint praise that Brown's life "shows how a man without perhaps extraordinary abilities may attain and honour the highest judicial position by industry, by good character, pleasant manners and some aid from fortune."[12] Another commentator concludes that "Brown, a privileged son of the Yankee merchant class, was a reflexive social elitist whose opinions of women, African‐Americans, Jews, and immigrants now seem odious, even if they were unexceptional for their time. Brown exalted, as he once wrote, 'that respect for the law inherent in the Anglo‐Saxon race.' Although he was widely praised as a fair and honest judge, Plessy has irrevocably dimmed his otherwise creditable career. Though some may argue that Brown bears personal guilt for the racial evils Plessy helped make possible, others respond that Brown was a man of his day, noting that the decades of de jure discrimination that came after Plessy merely reflected the zeitgeist."[13]

Papers

- Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit, Mich.

- Henry Billings Brown family papers, 1855-1913. 29 vols. and 1 wallet; collection contains Brown`s correspondence with his biographer (Charles A. Kent), diaries, expense books containing some brief diary entries, a catalog of Brown`s private library, and miscellaneous material about Brown that Kent collected in preparation for the biography.

- Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, Ill.

- Melville Weston Fuller papers, 1833-1951; 12 ft. (ca. 7,000 items); finding aid; correspondence.

- University of Michigan, Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, Mich.

- Thomas McIntyre Cooley papers, 1850-1898; 7 ft. and 16 vols.; finding aid; correspondence.

- Benjamin F. Graves papers, 1815-1950; 2.5 linear ft.; finding aid; correspondence.

- Frank Addison Manny papers, 1890-1955; 5 linear ft. and 4 vols.; finding aid; correspondence.

- University of Michigan lawyers` and judges` papers, 1820-1962; ca. 340 items and 55 vols.; assorted papers.

- John Patton papers, 1888-1905; 0.4 linear ft.; represented.

- Henry Wade Rogers papers, 1873-1898; 60 items and 1 vol.; finding aid; correspondence.

- Oliver Lyman Spaulding papers, 1861-1921; 3 linear ft. (ca. 35 items and 1 vol.); finding aid; correspondence.

- Peter White papers, 1849-1915; 23 ft. and 74 vols.; correspondence.

- Syracuse University, Department of Special Collections, Syracuse, N.Y.

- Elihu Root correspondence, 1874-1935; 127 items; finding aid; correspondence.

- Yale University, Sterling Memorial Library, New Haven, Conn.

- Brewer family papers, 1714-1954; 13.75 linear ft. (21 boxes, 1 folio, 4 vols.); finding aid; correspondence.[14]

References

- ↑ "Federal Judicial Center: Henry Billings Brown". December 11, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Memoir of Henry Billings Brown" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Federal Judicial Center: Henry Billings Brown". December 11, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Henry Billings (1876). Reports of admiralty and revenue cases argued and determined in the circuit and district courts of the United States for the western lake and river districts [1856-1875]. New York: Baker, Voorhis & Co.

- ↑ Brown, Henry Billings (1896). Cases on the Law of Admiralty. St. Paul: West Publishing Co. ISBN 978-1240089277.

- ↑ "Federal Judicial Center: Henry Billings Brown". December 11, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Memoir of Henry Billings Brown (Ambitions)" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Henry Billings Brown", Bio.

- ↑ Hales, Linda (August 13, 1992). "The Many-Storied Toutorsky Mansion; Historic 16th-Street Music School Opens for a 'Bare Bones' Preview". Washington Post. pp. T9.

- ↑ "Toutorsky Mansion: History". Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- ↑ "Henry Billings Brown" (PDF). Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Memoir of Henry Billings Brown (Praise)" (PDF). Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ↑ Entry for Henry Billings Brown by F. Helminski, in Kermit L. Hall (ed.), Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, 2nd edition, 2005 (ISBN 978-0195176612).

- ↑ Henry Billings Brown Research Collections

Further reading

- Kermit L. Hall (ed.), Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, 2nd edition, 2005 (ISBN 978-0195176612)

- Robert J. Glennon, Jr., Justice Henry Billings Brown: Values in Tension, University of Colorado Law Review 44 (1973): 553–604

- Henry Billings Brown at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Memoir of Henry Billings Brown, by Charles A. Kent of the Detroit Bar, 1915 (ISBN 978-1115062916)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Billings Brown. |

- Spartacus website on Henry Billings Brown

- Photograph, Henry Billings Brown Home, Washington, D.C.

- Henry Billings Brown Memorial at Find a Grave

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John Longyear |

Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan 1875–1890 |

Succeeded by Henry Swan |

| Preceded by Samuel Miller |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1890–1906 |

Succeeded by William Moody |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||