Homophile

| Part of a series on |

| Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people |

|---|

|

| Sexual orientation |

| History |

| Culture |

| Rights |

| Social attitudes |

| Prejudice / Violence |

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

The word homophile or homophilia is a dated term for homosexuality. The use of the word began to disappear with the emergence of the gay liberation movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, replaced by a new set of terminology which provides a much clearer identity such as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender, and in the 1990s terms like queer[1] came along and then collectively the LGBTQ tag become popularized. In the present day it is LGBTQIA,[2] still it is all considered under the umbrella term "Homophilia".

Etymology

The term homophile is favoured by some because it emphasizes love ("-phile" from Greek φιλία) rather than sex. Coined by the German astrologist, author and psychoanalyst Karl-Günther Heimsoth in his 1924 doctoral dissertation Hetero- und Homophilie, the term was in common use in the 1950s and 1960s by homosexual organizations and publications; the groups of this period are now known collectively as the homophile movement.

The Church of England has used the term "homophile" in certain contexts since at least 1991 – e.g., "homophile orientation," and "sexually active homophile relationship."[3]

In almost all languages where the words "homophile" and "homosexual" were both in use (i.e., their cognate equivalents: German Homophil and Homosexuel, Italian omofilo and omosessuale, etc.), "homosexual" won out as the modern conventional neutral term. One exception is Norwegian, where the opposite happened, and "homofil[i]" is the modern conventional neutral term for "homosexual[ity]" in Norwegian. Quoting and translating from the Norwegian (Nynorsk) Wikipedia article "Homofili":

[...] In English and American, "homophilia" was used to some extent; but by the end of the 1960s, it was replaced [in those languages] by "homosexual", "gay", and "lesbian". "Homofili" was first used in Norwegian in a 1951 brochure from the Norwegian branch of the Danish "League of 1948". Norway is one of the few countries where this trend [to use words based on "homophil-" instead of "homosexual-"] is still widespread.[4]

.jpg)

Homophile movement (1940–1970)

After the gains made by the homosexual rights movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the vibrant homosexual subcultures of the 20s and 30s became silent as war engulfed Europe. Germany, the traditional home of such movements (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee) and activists (Magnus Hirschfeld, Ernst Burchard, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs or Max Spohr), went from being the best place in Europe to be gay, lesbian or transgender, to the worst, under the Nazis. The Swiss journal Der Kreis ("the circle") was the only homosexual publication in Europe to publish during the Nazi era. Der Kreis was edited by Anna Vock, and later Karl Meier; the group gradually shifted from being female-dominated to male-dominated through the 1930s, as the tone of the magazine simultaneously became less militant.

After the war, organizations began to re-form, such as the Dutch COC in 1946. Other, new organizations arose, including Forbundet af 1948 ("League of 1948"), founded by Axel Axgil in Denmark, with Helmer Fogedgaard publishing an associated magazine called Vennen (The Friend) from January 1949 until 1953. Fogedgaard used the pseudonym "Homophilos," introducing the concept of "homophile" in May 1950, unaware that the word had been presented as an alternative term a few months previously by Jaap van Leeuwen, one of the founders of the Dutch COC. The word soon spread among members of the emerging post-war movement who were happy to emphasize the respectable romantic side of their relationships over genital sexuality.

A Swedish branch of Forbundet af 1948 was formed in 1949 and a Norwegian branch in 1950. The Swedish organization became independent under the name Riksförbundet för sexuellt likaberättigande (RFSL, "Federation for Sexual Equality") in 1950, led by Allan Hellman. The same year in the United States, the Mattachine Society was formed, and other organizations such as ONE, Inc. (1952) and the Daughters of Bilitis (1955) soon followed. By 1954, the monthly sales of ONE's magazine peaked at 16,000. Homophile organizations elsewhere include Arcadie (1954) in France and the British Homosexual Law Reform Society (founded 1958).

These groups are generally considered to have been politically cautious, in comparison to the LGBT movements that both preceded and followed them. Historian Michael Sibalis describes the belief of the French homophile group Arcadie, "that public hostility to homosexuals resulted largely from their outrageous and promiscuous behaviour; homophiles would win the good opinion of the public and the authorities by showing themselves to be discreet, dignified, virtuous and respectable."[5] However, while few were prepared to come out, they did risk severe persecution, and some figures within the Homophile movement such as the American communist Harry Hay were more radical.

In 1951, the president and vice-president of the Dutch COC initiated an International Congress of European homophile groups, which resulted in the formation of the International Committee for Sexual Equality (ICSE). The ICSE brought together, among other groups, the Forbundet of 1948 (Scandinavia), the Riksförbundet för Sexuellt Likaberättigande (Sweden), Arcadie (France), Der Kreis (Swiss), and, later, ONE (U.S.A.). Historian Leila Rupp describes the ICSE as a classic example of transnational organizing; "It created a network across national borders, nurtured a transnational homophile identity, and engaged in activism designed to change both laws and minds." However, the ICSE failed to last beyond the early 1960s due to poor attendance at meetings, lack of active leaders, and failure of members to pay dues.[6]

By the mid-1960s, gays, lesbians and transpeople in the United States were forming more visible communities, and this was reflected in the political strategies of American homophile groups. From the mid-1960s, they engaged in picketing and sit-ins, identifying themselves in public space for the first time. Formed in 1964, the San Franciscan Society for Individual Rights (SIR) had a new openness and a more participatory democratic structure. SIR was focused on building community, and sponsored drag shows, dinners, bridge clubs, bowling leagues, softball games, field trips, art classes and meditation groups. In 1966, SIR opened the nation's first gay and lesbian community center, and by 1968 they had over 1000 members, making them the largest homophile organization in the country. The world's first gay bookstore had opened in New York the year before. A 1965 gay picket held in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, according to some historians, marked the beginning of the modern gay rights movement. Meanwhile, in San Francisco in 1966, transgender street prostitutes in the poor neighborhood of Tenderloin rioted against police harassment at a popular all-night restaurant, Gene Compton's Cafeteria. These and other activities of public resistance to oppression lead to a feeling of Gay Liberation that was soon to give a name to a new movement.

In 1963, homophile organizations in New York City, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. joined together to form East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO) to more closely coordinate their activities. The success of ECHO inspired other homophile groups across the country to explore the idea of forming a national homophile umbrella group. This was done with the formation in 1966 of the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO, rhymes with Waco).[7] NACHO held annual conferences, helped start dozens of local gay groups across the country and issued position papers on a variety of LGBT-related issues. It organized national demonstrations, including a May 1966 action against military discrimination that included the country's first gay motorcade.[8] Through its legal defense fund, NACHO challenged anti-gay laws and regulations ranging from immigration issues and military service to the legality of serving alcohol to homosexuals.[9] NACHO disbanded after a contentious 1970 conference at which older members and younger members, radicalized in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall riots, clashed.[10] Gay Sunshine magazine declared the convention "the battle that ended the homophile movement".[11]

Organisations and publications

Denmark

- Forbundet af 1948 (1948–?) and Pan (1954–present)

- International Homosexual World Organisation (IHWO), 1952? – first half of the 1970s, political since second half of the 1960s, founded by Axel and Eigil Axgil, German chapter named: Internationale Homophile Welt-Organisation)

France

- Arcadie (journal, published 1954–1982), and organisation with the same name. Often published with the subtitle "Mouvement homophile de France".

Netherlands

- COC (1946–present) is the earliest homophile organisation. Their first magazine, Vriendschap (Friendship), was published from 1949 to 1964 and digitally available at IHLIA LGBT Heritage.[12] They also produced a number of other publications.

Sweden

- RFSL, Riksförbundet för sexuellt likaberättigande — "Federation for Sexual Equality", known since 2007 as the "Swedish Federation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights" (1950–present)

United Kingdom

- Homosexual Law Reform Society (1958–1970 when it was renamed as the Sexual Law Reform Society). The HLRS was formed as a response to the 1957 Wolfenden report. Most of the members were heterosexual.

- Campaign for Homosexual Equality (1964–present)

United States

- Vice Versa: America's Gayest Magazine (1947–1948), the first lesbian periodical in the United States, was free. Lisa Ben (an anagram of "lesbian"), the 25-year-old Los Angeles secretary who created Vice Versa, chose the name "because in those days our kind of life was considered a vice."

- Knights of the Clock (c. 1950–?); first interracial gay organization. Focused on social activities but also worked on employment and housing concerns for interracial couples.

- The Mattachine Society (1950–1987) and the Mattachine Review (1955–1966);[13] Homosexual Citizen, (published by the Washington chapter, 1966–?)

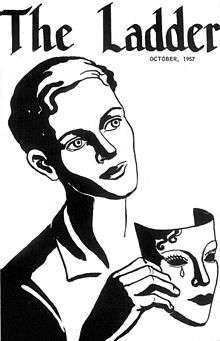

- The Daughters of Bilitis (1955–present) and The Ladder (1956–1972); Focus (published by the Boston chapter, 1971–1983); Sisters, (National, published in San Francisco, 1971–1975).

- ONE, Inc. (1952–present) and One magazine (1953–1972);[13] Homophile Studies (1958–1964)

- The League for Civil Education (1960 or 1961–?) and The LCE News (1961–?)

- The Janus Society (1962–1969) and DRUM magazine (1964–1969). A racy gay-male oriented magazine, DRUM reached a circulation of 10,000 by 1966.

- Society for Individual Rights (1964–1976)[13] and Vector (1965–1977)

- The Homosexual Law Reform Society (1965–1969)

- Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom, Kansas City MO, and The Phoenix: Midwest Homophile Voice, (1966–1972)

- Society Advocating Mutual Equality (SAME) (1966–1968), Rock Island IL, "The Challenger" newsletter

- Homophile Action League (Philadelphia) and the HAL Newsletter (1969–1970)

- Spiritual Friendship,[14] a Christian blog for gay writers seeking development of Church teaching (2013–Present)[15]

International

- International Committee for Sexual Equality (ICSE) (1951–1963); Formed by the Dutch COC and functioned as an umbrella organization that united many of the above national organizations from Europe and the United States. Published two German language periodicals, ICSE Kurier and ICSE-PRESS.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Queer - definition". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ "What Does LGBTQIA mean?". tahoesafealliance.org.

- ↑ Issues in Human Sexuality: A Statement by the House of Bishops of the General Synod of the Church of England, December 1991 (London: Church House Publishing, 1991). "Annotated Notes on Issues in Human Sexuality". Archived from the original on 3 February 2009.

- ↑ "Homofili", from Norsk (nynorsk) Wikipedia, entry retrieved 2012-06-19. Original text: “I den grad «homophile» hadde fått noko gjennomslag i engelsk og amerikansk, overtok «homosexual», «gay» og «lesbian» denne plassen frå slutten av 1960-talet. «Homofili» blei første gong nytta på norsk i ein brosjyre av den norske avdelinga av det danske «Forbundet af 1948» i 1951. Noreg er eit av dei få (det einaste?) landet der dette omgrepet framleis har stor utbreiing.”

- ↑ Sibalis, Michael, 2005. Gay Liberation Comes to France: The Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire (FHAR), French History and Civilization. Papers from the George Rudé Seminar. Volume 1 PDF link

- ↑ Rupp, Leila (2011). "The Persistence of Transnational Organizing: The Case of the Homophile Movement." The American Historical Review 116:4 (Oct. 2011): 1014-1039.

- ↑ Bianco, p. 174

- ↑ Fletcher, p. 42

- ↑ Bianco, p. 175

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 79

- ↑ Quoted in Armstrong, p. 79

- ↑ "Digitale Collectie". ihlia.nl (in Dutch). Vriendschap. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sexuality Studies at UC Davis, Sexuality Studies Resources Held in the UC Davis Shields Library's Special Collections Department". Retrieved April 8, 2006.

- ↑ "spiritualfriendship.org". spiritualfriendship.org. 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ "Musings on God, friendship, relationships". Spiritual Friendship. 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Elizabeth A. (2002). Forging Gay Identities: Organizing Sexuality in San Francisco, 1950–1994. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-02694-9.

- Bianco, David (1999). Gay Essentials: Facts For Your Queer Brain. Los Angeles, Alyson Books. ISBN 1-55583-508-2.

- Fletcher, Lynne Yamaguchi (1992). The First Gay Pope and Other Records. Boston, Alyson Publications. ISBN 1-55583-206-7.

.jpg)