Stonewall Inn

|

Stonewall Inn | |

|

2012; the building on the right was part of the property in 1969 | |

| Location |

53 Christopher Street Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°44′01.67″N 74°00′07.56″W / 40.7337972°N 74.0021000°WCoordinates: 40°44′01.67″N 74°00′07.56″W / 40.7337972°N 74.0021000°W |

| NRHP Reference # | 99000562 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 28, 1999[1] |

| Designated NHL | February 16, 2000[2] |

| Designated NMON | June 24, 2016 |

| Designated NYCL | June 23, 2015[3] |

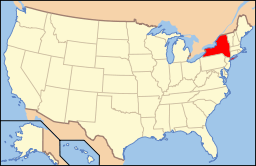

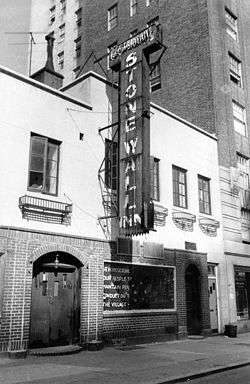

The Stonewall Inn, often shortened to Stonewall, is a gay bar and recreational tavern in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City, and the site of the Stonewall riots of 1969, which is widely considered to be the single most important event leading to the gay liberation movement and the modern fight for gay and lesbian rights in the United States.[1]

The original Inn, which closed in 1969, was located at 51–53 Christopher Street, between West 4th Street and Waverly Place.[4] In 1990 a bar called "Stonewall" opened in the western half of the original location (53 Christopher Street). This was renovated and returned to its original name, "The Stonewall Inn", in 2007. The buildings are both part of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission's Greenwich Village Historic District, designated in 1969, and the Inn was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2000.

On June 23, 2015, the Stonewall Inn was the first landmark in New York City to be recognized by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission on the basis of its status in LGBT history,[5] and on June 24, 2016, the Stonewall National Monument was named the first U.S. National Monument dedicated to the LGBTQ-rights movement.[6]

Establishment and occupation

Originally constructed between 1843 and 1846 as stables, the property functioned as a tearoom during the Prohibition-era, named Bonnie's Stone Wall after the owner, a woman named Bonnie. It was later converted into a restaurant called Bonnie's Stonewall Inn. The name was later changed to Stonewall Inn Restaurant.[7] It remained a restaurant until the interior was gutted by a fire in the mid-1960s.[8]

On March 18, 1967, the Stonewall opened in the space. It was, during its time, the largest gay establishment in the U.S. and was very favorable with the lesbian and gay population because of its intimate dance policy, although, as with most gay clubs at the time, police raids were common.[9] In late 1969, a few months after the rebellion that started on June 28 of that year, the Stonewall Inn closed.

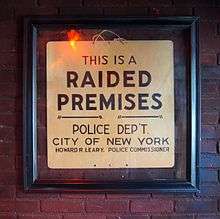

Stonewall Riots

In 1966, three members of the Mafia invested in the Stonewall Inn, turning it into a gay bar, after it had been a restaurant and a nightclub for heterosexuals. Once a week a police officer would collect envelopes of cash as a payoff; the Stonewall Inn had no liquor license. It had no running water behind the bar; used glasses were run through tubs of water and immediately reused. There were no fire exits, and the toilets overran consistently. Though the bar was not used for prostitution, drug sales and other "cash transactions" took place. It was the only bar for gay men in New York City where dancing was allowed; dancing was its main draw since its re-opening as a gay club. Police raids on gay bars were very common, often happening once a month for each bar. Many bars kept extra liquor in a secret panel behind the bar, or in a car down the block, to facilitate resuming business as quickly as possible if alcohol was seized. Bar management usually knew about raids beforehand due to police tip-offs, and raids occurred early enough in the evening that business could continue after the police had finished.

Riots

The Stonewall riots were a series of violent demonstrations by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969 at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich neighborhood of New York City. Around 1:20 a.m. on June 28, 1969, Seymour Pine of the New York City Vice Squad Public Morals Division and four other officers joined forces with two male and two female undercover police officers who were already stationed inside the bar, the lights on the dance floor flashed, signaling their arrival.[10] However, the raid did not go as planned. Because the patrol wagons responsible for transporting the arrested patrons and the alcohol from the bar took longer than expected, a crowd of released patrons and by-standers began to grow outside of the Inn. This number would swell to much larger numbers as the night would go on. Writer David Carter notes that the police officers eventually became so afraid of the crowd that they refused to leave the bar for forty-five minutes.

The last straw came when a scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs was escorted from the door of the bar to the waiting police wagon several times. She escaped repeatedly and fought with four of the police, swearing and shouting, for about ten minutes. Bystanders recalled that the woman, whose identity remains unknown, sparked the crowd to fight when she looked at bystanders and shouted, "Why don't you guys do something?" After an officer picked her up and heaved her into the back of the wagon, the crowd became a mob and went "berserk": "It was at that moment that the scene became explosively violent."

The police tried to restrain some of the crowd, and knocked a few people down, which incited bystanders even more. The riots would go on to escalate to the point where the Tactical Police Force (TPF) of the New York City Police Department arrived to free the trapped police officers inside the Stonewall. The TPF formed a phalanx and attempted to clear the streets, and by 4:00 in the morning they were able to do so.

Aftermath

After the initial riots were cleared, the feeling of urgency and aggression began to spread throughout all of Greenwich Village. The riots would continue for a few days afterwards. However, the riots turned into altercations between the police and the Village people, different from the open violence shown the morning of the beginning of the riots. Interestingly enough, even people who had not seen the riots at the Inn began to become a part of the aftermath. Many were emotionally moved by the events and began to attend meetings in an effort to take action. Many look to the riots at Stonewall as being the birthplace of the modern gay rights movement.

Legacy

The riots spawned from a bar raid became a literal example of gays, lesbians, bisexuals and trans people fighting back, and a symbolic call to arms for many people. Within two years of the Stonewall riots there were gay rights groups in every major American city, as well as Canada, Australia, and Western Europe. The Stonewall riots marked such a significant turning point that many aspects of prior gay and lesbian culture, such as bar culture formed from decades of shame and secrecy, were forcefully ignored and denied.

The events that took place at the Stonewall Inn led to the first gay pride parades in the United States and in many other countries. On June 28, 1970, a march was led from Greenwich Village to the Sheep Meadow in Central Park.[11]

Each year during the Pride March crowds gather outside the Stonewall Inn to celebrate its rich history.

After the riots

Over the next twenty years, the space was occupied by various other establishments, including a bagel sandwich shop, a Chinese restaurant, and a shoe store. Many visitors and new residents in the neighborhood were unaware of the building's history or its connection to the Stonewall riots. In the early 1990s, a new gay bar, named simply "Stonewall", opened in the west half of the original Stonewall Inn. Around this time, the block of Christopher Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues was co-named "Stonewall Place."

In June 1999, through the efforts of the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation and the Organization of Lesbian and Gay Architects and Designers, the area including Stonewall was listed on the National Register of Historic Places[12] for its historic significance to gay and lesbian history. The area delineated included the Stonewall Inn, Christopher Park, and portions of surrounding streets and sidewalks. The area was declared a National Historic Landmark in February 2000.[2][13][14]

The building was renovated in the late 1990s and became a popular multi-floor nightclub, with theme nights and contests. The club gained popularity for several years, gaining a young urban gay clientele until it closed again in 2006, due to neglect, gross mismanagement, and noise complaints from the neighbors at 45 Christopher Street.[15]

In January 2007, it was announced that the Stonewall Inn was undergoing major renovation under the supervision of local businessmen Bill Morgan and Kurt Kelly, as well as the only female lesbian investor, Stacy Lentz, who ultimately reopened the Stonewall Inn in March 2007.[16] Subsequently regaining popularity and continuing to pay homage to its historic significance, the Stonewall Inn hosts a variety of local music artists, drag shows, trivia nights, cabaret, karaoke and private parties. Since the landmark passage of New York State's Marriage Equality Act the inn now offers gay wedding receptions as well. Kelly, Morgan, and Lentz have also been dedicated to incorporating various fundraising events for a host of LGBT non-profit organizations.

In June 2014, the Stonewall 45 exhibit, sponsored by the Arcus Foundation and the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, memorialized the 45th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising with posters in the windows of Christopher Street businesses, including the Stonewall Inn. On May 29, 2015, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission announced it would officially consider designating Stonewall as a landmark, the first city location to be considered based on its LGBT cultural significance alone – and on June 23, 2015, it did so.[17][18] The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation kept up advocacy efforts for this over the tenures of two New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission chairs.[19][20] Stonewall thus became the first LGBT-history site in the country listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, and the first LGBT-history site in New York City.

In June 2016, U.S. President Barack Obama established a 7.7-acre area around the site as the Stonewall National Monument, America's first LGBT national park site.[21]

In popular culture

- The movie Stonewall, released in 1995, is loosely based on the incidents leading up to the Stonewall riots.

- Brazilian singer Renato Russo recorded his first solo album, The Stonewall Celebration Concert, in 1994, celebrating the 25th anniversary of the riots. The booklet accompanying the album contained information about 29 social organizations, several of which related to gay rights; part of the royalties was donated to such organizations.

- The 2012 play Hit the Wall, by Ike Holter, is a dramatic retelling of the Stonewall riots.[22]

- The 2015 movie Stonewall, directed by Independence Day's Roland Emmerich, is a coming-of-age drama focused on a fictional, young gay male protagonist. It takes place during the time shortly before and during the famed 1969 Stonewall riots. It stars Jeremy Irvine, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Ron Perlman, and Caleb Landry Jones.[23]

- The upcoming short film Happy Birthday, Marsha! is a fictional account of the lives of Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in the hours leading up to the Stonewall uprising, featuring Mya Taylor as Johnson.[24]

See also

- Stonewall National Monument

- LGBTQ culture in New York City

- List of New York City Landmarks

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

- List of National Monuments of the United States

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

References

- 1 2 National Park Service (2008). "Workforce Diversity: The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". US Department of Interior. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- 1 2 National Historic Landmarks Program (2008). "Stonewall". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ↑ Brazee, Christopher D. et al. (June 23, 2015) Stonewall Inn Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission

- ↑ "The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street, interactive Google Street View image and map". Geographic.org/streetview. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- ↑ Associated Press (June 23, 2015). "NYC grants landmark status to gay rights movement building". North Jersey Media Group. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ↑ Eli Rosenberg (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ↑ http://www.stonewallvets.org/Stonewall_Era_Club_People_Rebellion.htm#name

- ↑ "Christopher Park Monuments - Gay Liberation : NYC Parks". www.nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2016-06-24.

- ↑ Carter, David (2005). Stonewall: The rebellion That Sparked the Gay Revolution (First ed.). New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-34269-1.

- ↑ "Gale - Enter Product Login". go.galegroup.com. Retrieved 2016-11-17.

- ↑ Fosburgh, Lacey (June 29, 1970). "Thousands of Homosexuals Hold a Protest Rally in Central Park". The New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Report" (PDF). Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ↑ David Carter; Andrew Scott Dolkart; Gale Harris & Jay Shockley (27 May 1999). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Stonewall (Text)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ↑ David Carter; Andrew Scott Dolkart; Gale Harris & Jay Shockley (27 May 1999). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Stonewall (Photos)" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

- ↑ Halbfinger, David M. (29 July 1997). "For a Bar Not Used to Dancing Around Issues, Dancing Is Now the Issue". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ http://www.gomag.com/article/100_women_we_love_stacy_l/

- ↑ Humm, Andy (29 May 2015). "EXCLUSIVE: Stonewall Inn Appears Headed for City Landmarks Status – A Gay First". Gay City News. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "Stonewall Inn Designation Report" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Berman, Andrew. "Letter to LPC Chairman Robert Tierney" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ Berman, Andrew. "Letter to LPC Chair Meenakshi Srinivasan" (PDF). Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "President Obama Designates Stonewall National Monument". The White House. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Jones, Chris. "'Hit the Wall' is a raw, ambitious telling of historic fight for gay rights(12 Feb 2012)". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ Stonewall (2015) at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Happy Birthday Marsha official website

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stonewall Inn. |

- Official website

- The Stonewall Riots – About.com

- Original Stonewall Inn to close – Pinknews.co.uk