Hong Kong 1967 Leftist riots

| Hong Kong 1967 riots | |

|---|---|

|

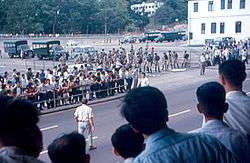

Confrontation between rioters and the Hong Kong Police Force | |

| Date | May - December 1967 |

| Location | Hong Kong |

| Methods | Demonstrations, strikes, assassinations, planting of bombs, |

| Status | Leftists failed to take over Hong Kong |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 52 |

| Injuries | 802[1] |

| Arrested | 1936[1] |

| Hong Kong 1967 Leftist riots | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 六七暴動 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

Hong Kong 1967 Leftist riots refers to the large-scale leftist riots between pro-communists and their sympathizers, and the establishment.

While originating as a minor labour dispute, the tensions later grew into large scale demonstrations against British colonial rule. Demonstrators clashed violently with the Hong Kong Police Force.

Instigated by events in the People's Republic of China (PRC), leftists called for massive strikes and organised demonstrations, while the police stormed many of the leftists' strongholds and placed their active leaders under arrest.

These riots became still more violent when the leftists resorted to terrorist attacks, planting fake and real bombs in the city and murdering some members of the press who voiced their opposition to the violence.

Tensions

The initial demonstrations and riots were labour disputes that began as early as March 1967 in shipping, taxi, textile, cement companies and in particular the Hong Kong Artificial Flower Works, where there were 174 pro-communist trade unionists.[2] The unions that took up the cause were all members of the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions with strong ties to Beijing.[3]

The political climate was tense in Hong Kong in the spring of 1967. To the north of the British colony's border, the PRC was in turmoil. Red Guards carried out purges and engaged in infighting, while riots sponsored by pro-Communist leftists erupted in the Portuguese colony of Macau, to the west of Hong Kong, in December 1966.

Despite the intervention of the Portuguese army, order was not restored to Macau; and after a general strike in January 1967, the Portuguese government agreed to meet many of the leftist demands, placing the colony under the de facto control of the PRC.[4] The tension in Hong Kong was heightened by the ongoing Cultural Revolution to the north. Up to 31 protests were held.[5]

Outbreak of violence

In May, a labour dispute broke out in an artificial flower factory in San Po Kong.[6] This was owned by Li Ka-shing.[7] Picketing workers clashed with management, and riot police were called in on 6 May. In violent clashes between the police and the picketing workers, 21 workers were arrested; many more were injured. Representatives from the union protested at police stations, but were themselves also arrested.

The next day, large-scale demonstrations erupted on the streets of Hong Kong. Many of the pro-communist demonstrators carried Little Red Books in their left hands and shouted communist slogans. The Hong Kong Police Force engaged with the demonstrators and arrested another 127 people.[8] A curfew was imposed and all police forces were called into duty.[9]

In the PRC, newspapers praised the leftists' activities, calling the British colonial government's actions "fascist atrocities".[10] On 22 August in Beijing, thousands of people demonstrated outside the office of the British chargé d'affaires, before Red Guards attacked and ransacked the main building, and then burning it down.[11]

In Hong Kong's Central District, large loudspeakers were placed on the roof of the Bank of China Building, broadcasting pro-communist rhetoric and propaganda, prompting the British authorities to retaliate by putting larger speakers blaring out Cantonese opera.[9] Posters were put up on walls with slogans like "Blood for Blood", "Stew the White-Skinned Pig", "Fry The Yellow Running Dogs", "Down With British Imperialism" and "Hang David Trench", a reference to the then Governor.[12] Students distributed newspapers carrying information about the disturbances and pro-communist rhetoric to the public.

On 16 May, the leftists formed the Hong Kong and Kowloon Committee for Anti-Hong Kong British Persecution Struggle.[13] Yeung Kwong of the Federation of Trade Unions was appointed as its chairman. The Committee organised and coordinated a series of large demonstrations. Hundreds of supporters from 17 different leftist organisations demonstrated outside Government House, chanting communist slogans.[14] At the same time, many workers took strike action, with Hong Kong's transport services being particularly badly disrupted.

More violence erupted on 22 May, with another 167 people being arrested. The rioters began to adopt more sophisticated tactics, such as throwing stones at police or vehicles passing by, before retreating into leftist "strongholds" such as newspaper offices, banks or department stores once the police arrived.

The height of the violence

On 8 July, several hundred demonstrators from the PRC, including members of the People's Militia, crossed the frontier at Sha Tau Kok and attacked the Hong Kong Police, of whom five were shot dead and eleven injured in the brief exchange of fire.[15] The People's Daily in Beijing ran editorials supporting the leftist struggle in Hong Kong; rumours that the PRC was preparing to take over control of the colony began to circulate. The leftists tried in vain to organise a general strike; attempts to persuade the ethnic Chinese serving in the police to join the pro-communist movement were equally unsuccessful.

The British Hong Kong Government imposed emergency regulations, granting the police special powers in an attempt to quell the unrest. Leftists newspapers were banned from publishing; leftist schools were shut down; many leftist leaders were arrested and detained, and some of them were later deported to the PRC.

The leftists retaliated by planting more bombs. Real bombs, mixed with even more decoys, were planted throughout the city. Normal life was severely disrupted and casualties began to rise. A seven-year-old girl, Wong Yee Man, and her two-year-old brother, Wong Siu Fan, were killed by a bomb wrapped like a gift placed outside their residence.[16] Bomb disposal experts from the police and the British forces defused as many as 8000 home-made bombs, of which 1100 were found to be real.[17] These were known as "pineapple" bombs.[18] [1]

On 19 July, leftists set up barbed wire defences on the 20-storey Bank of China Building (owned by the PRC government).[19]

In response, the police fought back and raided leftist strongholds, including Kiu Kwan Mansion.[18] In one of the raids, helicopters from HMS Hermes – a Royal Navy carrier – landed police on the roof of the building.[20] Upon entering the building, the police discovered bombs and weapons, as well as a leftist "hospital" complete with dispensary and an operating theatre.[8]

The public outcry against the violence was widely reported in the media, and the leftists again switched tactics. On 24 August, Lam Bun, a popular anti-leftist radio commentator, was murdered by a death squad posing as road maintenance workers, as he drove to work with his cousin; prevented from getting out of his car, he was burned alive.[21]

Other prominent figures of the media who had voiced opposition against the riots were also threatened, including Louis Cha, then chairman of the Ming Pao newspaper, who left Hong Kong for almost a year before returning.

The waves of bombings did not subside until October 1967. In December, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai ordered the leftist groups in Hong Kong to stop all bombings; and the riots in Hong Kong finally came to an end. The disputes in total lasted 18 months.[22]

It became known much later that, during the riots, the commander of PLA's Guangzhou Military Region Huang Yongsheng (one of Lin Biao's top allies) secretly suggested invading and occupying Hong Kong, but his plan was vetoed by Zhou Enlai.[23]

Aftermath

Casualties

By the time the rioting subsided at the end of the year, 51 people had been killed, of whom 15 were died in bomb attacks, with 832 people sustaining injuries, while 4979 people were arrested and 1936 convicted.[8] Millions of dollars in property damage resulted from the rioting, far in excess of that reported during the 1956 riot.[22] Confidence in the colony's future declined among some sections of Hong Kong's populace, and many residents sold their property and relocated overseas.

| Name | Age | Date | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chan Kwong Sang (陳廣生) | 13 | 1967-05-12 | A student barber, beaten to death by riot police squad at Wong Tai Sin Resettlement Area. |

| Tsui Tin Por (徐田波) | 42 | 1967-06-08 | A worker in the Mechanics Division of the Public Works Department, beaten to death at Wong Tai Sin Police Station after arrest. |

| Lai Chung (黎松) | 52 | 1967-06-08 | A Towngas worker, shot by police in a raid, then killed by drowning. |

| Tsang Ming (曾明) | 29 | 1967-06-08 | A Towngas worker, beaten to death by police in a raid. |

| Tang Tsz Keung (鄧自強) | 30 | 1967-06-23 | A plastics factory worker, shot by police in a raid against a trade union. |

| Lee On (李安) | 45 | 1967-06-26 | A worker at Shaw Brothers, died while being admitted to hospital from a law court. |

| Chow Chung Sing (鄒松勝) | 34 | 1967-06-28 | A plastics factory worker, beaten to death by police after arrest. |

| Law Chun Kau (羅進苟) | 30 | 1967-06-30 | A plastics factory worker, beaten to death by police after arrest. |

| Fung Yin Ping (馮燕平)[24] | 40 | 1967-07-08 | A Chinese police corporal, killed by militia from Mainland China at Sha Tau Kok |

| Kong Shing Kay (江承基)[24] | 19 | 1967-07-08 | A Chinese police constable, killed by militia from Mainland China at Sha Tau Kok |

| Mohamed Nawaz Malik[24] | 28 | 1967-07-08 | A Pakistani police constable, killed by militia from Mainland China at Sha Tau Kok |

| Khurshid Ahmed[24] | 27 | 1967-07-08 | A Pakistani police constable, killed by militia from Mainland China at Sha Tau Kok |

| Wong Loi Hing (黃來興)[24] | 27 | 1967-07-08 | A Chinese police constable, killed by militia from Mainland China at Sha Tau Kok |

| Zhang Tiansheng (張天生) | 41 | 1967-07-08 | A militiaman from Mainland China, shot to death by Hong Kong Police at Sha Tau Kok |

| Cheng Chit Po (鄭浙波) | 32 | 1967-07-09 | A porter working in Western District, shot to death when attempting to save a student from leftist school being pursued by police. |

| Ma Lit (馬烈) | 43 | 1967-07-09 | A porter working in Western District, shot to death when attempting to save a student from leftist school being pursued by police. |

| Lam Po Wah (林寶華)[24] | 21 | 1967-07-09 | A Chinese police constable, killed by a stray bullet after Cheng Chit Po and Ma Lit were shot to death. |

| Choi Nam (蔡南) | 27 | 1967-07-10 | A leftist protester, shot to death by police in Johnston Road, Wan Chai. |

| Lee Chun Hing (李振興) | 35 | 1967-07-10 | A furniture worker, beaten to death by leftist protesters in Johnston Road, Wan Chai. |

| Lee Si (李四) | 48 | 1967-07-11 | A leftist protester, shot to death by police at Johnston Road, Wan Chai. |

| Mak Chi Wah (麥志華) | 1967-07-12 | A leftist protester, shot to death by police at Un Chau Street, Sham Shui Po. | |

| Yue Sau Man (余秀文) | 1967-07-15 | An employee of Wheelock Spinners, shot to death by police. | |

| Ho Fung (何楓) | 1967-07-16 | A worker at Kowloon Dockyard, shot to death by police at Kowloon City Police Station. | |

| So Chuen (蘇全) | 28 | 1967-07-26 | A worker from a textile factory, shot to death by police at Mong Kok while attacking a bus in service. |

| Ho Chuen Tim (何傳添) | 1967-08-09 | A fisherman from Sha Tau Kok, arrested during a police raid against memorial meeting for killed leftist workers on 24 June. Died on 9 August. | |

| Wong Yee Man (黃綺文)[16] | 8 | 1967-08-20 | An 8-year-old girl, killed, along with her younger brother, by a homemade bomb wrapped like a gift at Ching Wah Street, North Point. |

| Wong Siu Fan (黃兆勳)[16] | 4 | 1967-08-20 | Younger brother of Wong Yee Man. |

| Lam Bun (林彬) | 37 | 1967-08-25 | A radio commentator at Commercial Radio Hong Kong, ambushed and burned alive by a group of leftist men posing as road maintenance workers during his way to office on 24 August. Died on 25 August. |

| Charles Workman | 26 | 1967-08-28 | A sergeant in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, killed when a homemade bomb he was defusing at Lion Rock exploded. |

| Ho Shui Ki (何瑞祺) | 21 | 1967-08-29 | A mechanical worker, shot to death by police at Tung Tau Village, Wong Tai Sin. |

| Lam Kwong Hoi (林光海) | 1967-08-30 | A technician at Commercial Radio Hong Kong, burned alive with his elder cousin Lam Bun during his way to office on 24 August. Died on 30 August. | |

| Aslam Khan | 22 | 1967-09-03 | A firefighter, killed by a homemade bomb during defusing. |

1960s leftist groups

Many leftist groups with close ties to the PRC were destroyed during the riots of 1967. Public support for the pro-communist leftists sank to an all-time low, as the public widely condemned their violent behaviour. The murder of radio host Lam Bun, in particular, outraged many Hong Kong residents. The credibility of the PRC and its local sympathizers among Hong Kong residents was severely damaged for more than a generation.

New leftist groups and legacy

Some of the members who participated in the 1967 riot have since regained a foothold in Hong Kong politics during the early 1990s. Tsang Tak-sing, a communist party supporter and riot participant, later became the founder of the pro-Beijing Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong. Along with his brother Tsang Yok-sing, they continued to acknowledge Marxism in Hong Kong.[25]

In 2001, Yeung Kwong, a pro-Communist party activist of the 1960s, was awarded the Grand Bauhinia Medal under Tung Chee-hwa, a symbolic gesture that raised controversy as to whether the post-1997 Hong Kong government of the time was approving the riot.[26]

Legacy

The Hong Kong Police Force was applauded for its behaviour during the riots by the British Government. In 1969, Queen Elizabeth granted the Police Force the privilege of the "Royal" title. This title was to remain in use until the end of British rule in 1997.[27]

Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing went on to become Hong Kong's most important Chinese real estate developer.[28] Chinese philosopher and educator, Chien Mu, founder of the New Asia College (now part of the Chinese University of Hong Kong) left for Taiwan.[29] He was appointed to the Council for Chinese Cultural Renaissance by President Chiang Kai-shek.[30]

HK Police revisionism controversy

In mid-September 2015, media reported that the Hong Kong Police had made material deletions from its website concerning "police history", in particular, the political cause and the identity of the groups responsible for the 1967 riots, with mention of communists and Maoists being expunged.

For example, "Bombs were made in classrooms of left-wing schools and planted indiscriminately on the streets" became "Bombs were planted indiscriminately on the streets"; the fragment "waving aloft the Little Red Book and shouting slogans" disappeared, and an entire sentence criticising the hypocrisy of wealthy pro-China businessmen, the so-called "red fat cats" was deleted.[31]

The editing gave rise to criticisms that it was being sanitised, to make it appear that the British colonial government, rather than leftists, were responsible. Stephen Lo, the new Commissioner of Police, said the content change of the official website was to simplify it for easier reading; Lo denied that there were any political motives, but his denials left critics unconvinced.[32] The changes were subsequently reversed.

Depiction in the media

- In John Woo's action movie Bullet in the Head, the 1967 Riots are briefly shown.

- In the play/film I Have a Date with Spring, the riots (although only briefly referenced) are a key plot point.

- Wong Kar Wai's movie 2046 features backdrop of the riots, mentions of the riots and a few old newsreels of the rioting.

- The film about modern Hong Kong history Mr.Cinema depicts the riots.

See also

- 1960s in Hong Kong

- Chung Ying Street

- Hong Kong 1956 riots

- Hong Kong 1966 riots

- Spring Garden Lane

- Hong Kong 1981 riots

- 12-3 incident, a Leftist riot in Macau

References

- 1 2 3 "Police rewrite history of 1967 Red Guard riots". Hong Kong Free Press. 14 September 2015.

- ↑ Fire on the rim: a study in contradictions in left-wing political mobilization in Hong Kong, 1967, Stephen Edward Waldron, Syracuse University, 1976, page 65

- ↑ Political Change and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Hong Kong, Ian Scott, University of Hawaii Press, 1989, page 99

- ↑ Portugal, China and the Macau Negotiations, 1986-1999, Carmen Amado Mendes, Hong Kong University Press, 2013, page 34

- ↑ Hong Kong, C.W Lam and Cecilia L.W Chan, Professional Ideologies and Preferences in Social Work: A Global Study, Idit Weiss, John Gal, John Dixon, Praeger Greenwood Publishing, 2003, page 107

- ↑ Colony in Conflict: The Hong Kong Disturbances, May 1967-January 1968, John Cooper, Swindon Book Company, 1970, page iii

- ↑ A Modern History of Hong Kong, Steve Tsang, I.B.Tauris, 2007, page 183

- 1 2 3 Hong Kong's Watershed: The 1967 Riots, Gary Ka-wai Cheung, Hong Kong University Press, 2009, page 32, page 86, page 123

- 1 2 Where There Are Asians, There Are Rice Cookers: How "National" Went Global via Hong Kong, Yoshiko Nakano, Hong Kong University Press, 2009, page 4

- ↑ Survey of People's Republic of China Press, Issues 4032-4051, US Consulate General, 1967, pages 23-25

- ↑ The New Cambridge Handbook of Contemporary China, Colin Mackerras, Cambridge University Press, 2001, page 10

- ↑ May Days in Hong Kong: Riot and Emergency in 1967, Robert Bickers, Ray Yep, Hong Kong University Press, 2009, page 72

- ↑ May Upheaval in Hongkong, Committee of Hongkong-Kowloon Chinese Compatriots of All Circles for the Struggle Against Persecution by the British Authorities in Hongkong, 1967, page 8

- ↑ Asian Recorder, Volume 13, 1967, page 7832

- ↑ Hong Kong (Border Incidents), Hansard, HC Deb 10 July 1967 vol 750 cc93-7

- 1 2 3 Then & now: these were our children, South China Morning Post, 19 August, 2012

- ↑ Underground Front: The Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press, 2010, page 113

- 1 2 North Point tour takes participants back to the 1967 Hong Kong riots, South China Morning Post, 6 October, 2013,

- ↑ Bonavia, David (19 July 1967). "No Need for More Hongkong Troops". The Times. London. p. 4. ISSN 0140-0460.

- ↑ Justice in Hong Kong, Carol A. G. Jones, Routledge-Cavendish, 2007, page 402

- ↑ Orientations: Mapping Studies in the Asian Diaspora, Kandice Chuh, Karen Shimakawa, Duke University Press, 2001, page 205

- 1 2 Chu, Yingchi. [2003] (2003). Hong Kong Cinema: Coloniser, Motherland and Self. Routledge publishing. ISBN 0-7007-1746-3

- ↑ Revealed: the Hong Kong invasion plan, Michael Sheridan, The Sunday Times, 24 June 2007

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 In Memory of Those Members of the Royal Hong Kong Police Force and the Hong Kong Police Force Who Lost Their Lives in the Course of Duty, Hong Kong Police Force

- ↑ Hong Kong and the Reconstruction of China's Political Order, Suzanne Pepper in Crisis and Transformation in China's Hong Kong, Ming K. Chan, Alvin Y. So, M.E. Sharpe, 2002, page 64

- ↑ Introduction: The Hong Kong SAR in Flux, Ming K. Chan in Crisis and Transformation in China's Hong Kong, Ming K. Chan, Alvin Y. So, M.E. Sharpe, 2002, page 15

- ↑ A Battle Royal Rocks Imperial Yacht Club, Christian Science Monitor, 10 June 1996

- ↑ Entrepreneurship and Economic Development of Hong Kong, Routledge, Tony Fu-Lai Yu, 1997 page 64.

- ↑ Asiaweek, Volume 16, Issues 27-39, 1990, page 58

- ↑ Religion in Modern Taiwan: Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society, Philip Clart, Charles Brewer Jones, University of Hawaii Press, 2003, page 56

- ↑ "Why are the police tampering with 1967 riots history?". EJ Insight.

- ↑ "Police chief defends editing of '1967 riots' history on website". EJ Insight. 16 September 2015.

Further reading

- Cooper, John (1970). Colony in Conflict: The Hong Kong Disturbances, May 1967-January 1968. Hong Kong: Swindon Book Company. ASIN B009M72TM4. OCLC 833430183.

- Bickers, Robert; Yep, Ray (1 August 2009). May Days in Hong Kong: Riot and Emergency in 1967. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622099999.

- Cheung, Gary Ka-wai (1 October 2009). Hong Kong's Watershed: The 1967 Riots. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622090897.