Hugh T. Keyes

| Hugh Keyes | |

|---|---|

Hugh Keyes | |

| Born |

Hugh Tallman Keyes 1888 Trenton, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | 1963 |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater |

Harvard University U.S. Naval Academy |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | Significant houses in Bloomfield Hills and Grosse Pointe, Michigan |

| Design | Regency (mostly French) houses of white brick |

Hugh Tallman Keyes (1888 – 1963) was a noted early to mid 20th-century American architect. He designed grand estates for some of “Detroit’s most important clans”[1] and business magnates (such as Ford, Fisher, Bugas, Scherer, Stroh, Knudsen, and indirectly Taubman, Hermelin, and Caldwell), as well as the families of Michigan Governors. He is considered “one of the most prolific and versatile architects of the period.”[2]

Career

Keyes studied architecture at Harvard University (where his drawings won an honorable mention in the “Intercollegiate Architecture Competition, the most important event in the collegiate architecture world”[3]) and subsequently worked under architect C. Howard Crane[4] and was an associate of Albert Kahn[5] (“the foremost industrial architect of the United States”[6])—where he worked on Kahn’s “signature project”[7] the Neo-Renaissance Detroit Athletic Club. Keyes also graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy[4] and served as an ensign in the Navy during World War I and as a major in the Army during World War II.[8]

He travelled extensively in England, France, Italy, and Switzerland,[4] all of which influenced the development of his architectural style.

Keyes opened his own office in Detroit in 1921,[2] and his career spanned the roaring twenties, the Great Depression, and into the post war boom mid-century modern period. Keyes’s style ranged from Tudor Revival (the most ubiquitous style in the early 20th-century metropolitan area) to rustic Swiss chalets, but he is most noted for the Georgian/Palladian and symmetrical bow-fronted wings, wrought iron balconies, and hipped roofs (often with parapets or mansards) of the related Regency style of architecture.[9]

Keyes’s houses were known for being “built for the ages” (typically of “concrete and steel construction”)[10] and devoid of frills or affectation, his “free use of classical forms” done “without trickery or ostentation.”[11]

Keyes’s designs often included glass-walled conservatories, exploiting natural light from hillsides or lakesides. He was one of the Detroit architects that frequently employed architectural sculptor Corrado Parducci to embellish his designs.[12]

Keyes played an active role in the creation of the Cranbrook Institute of Science in 1933 (in the vicinity of which he would create many residences), and was one of its original honorary members.[13]

Commenting on the technological and aesthetic trend in modern architecture, Keyes observed:

| “ | The World today is being made over to fit a new tempo of life, and it is unthinkable that Detroit, leading the country in the advance of industrial design, should be content to live in homes of the past.[9] | ” |

Personal

Keyes was married to Faye Elizabeth Keyes, and had two daughters and two sons. He lived most of his adult life in Birmingham, Michigan.

Principal works

At the end of his career, Keyes identified his “principal works” as the John Bugas residence (Woodland), the Louis Goad residence, the Max Fisher residence, and the Benson Ford residence (Woodley Green).[8] Also considered significant among his works are the Robert Scherer residence, the Robert Hudson Tannahill residence, the Semon Knudsen residence, the Charles Welch residence, and the Lloyd Buhs residence.

Woodland

Vaughan Rd., Bloomfield Hills (1959)

Client: John S. Bugas

Style: Regency, Second Empire

Secluded far beyond its high split-stone walls, groves of spruce and birch, and private winding drive, Woodland[14] is one of the last and the most published of Keyes’s houses.[15][16][17][18] The Regency manor house features French (Second Empire) elements such as a copper hipped and mansard roofline and Keyes’s signature symmetrical bow-fronted wings and wrought iron balconies. Pedimented gables and extending portico-connected wings also evoke the Palladian style, while the house’s elegant mansard, white painted brick construction, leaded oval glass front windows and soaring central window interrupting the roofline are distinctive markers of the more French-influenced Regency Moderne style (or Hollywood Regency style). The south side of the house features Keyes’s natural light-filled garden room (conservatory), open living room, and library.[18] It sits on a wooded knoll overlooking the country estate’s expansive ornamental gardens and orchards and adjacent Eliel Saarinen-designed Cranbrook Kingswood[19] (called by The New York Times “one of the greatest campuses ever created anywhere in the world”[20]). A list of renowned designers have contributed to Woodland’s “pedigreed architecture”:[18] Eliel’s son Eero Saarinen was at the time renovating his own Victorian house nearby on Vaughan Road and worked informally with Keyes; French designer Andrée Putman—“the doyenne of contemporary French design”[21] who created hotels and homes (though “Putman rarely accept[ed] commissions for private residences except for very close friends, such as Karl Lagerfeld [and the Taubmans]”[21]) in Paris, New York, Brussels, and Monte Carlo (as well as designed the Air France Concorde interior)[17]—designed seven of Woodland’s bathrooms[22] and added an enormous spa with antique Italian glass mosaic tiles and a domed ceiling with a “luminous cornice”[15][17] (“Putman’s baths are legendary,” according to Architectural Digest, what she called “the core of a home”[21]); and William Hodgins,[23] “one of the deans of American interior decoration,”[18] later made additional and notable Regency interior modifications.[15][18] Woodland has been the home of a succession of prominent Michigan businessmen: John S. Bugas[24] (local FBI head and second in command at Ford Motor Company behind Henry Ford II[25]—hence the Ford-built, detached industrial power house serving the main house, similar to those of Henry’s and Edsel’s houses), for whom it was originally designed by Keyes; (real estate heir) Robert S. Taubman, whose extensive renovations were featured in Vogue magazine[15] (Woodland is also known as the Taubman House); and (hedge fund manager) Mark W. Spitznagel, its present owner.

Goad House

Lone Pine Rd., Bloomfield Hills (1955)

Client: Louis Clifford Goad

As the center of industrial wealth in the region shifted from Grosse Pointe to Bloomfield Hills, so too did Keyes’s projects. Keyes had already been working in Bloomfield Hills (starting in the 1930s—see Welch and Lake Park House below) when Louis Clifford Goad (Executive Vice President of General Motors Company[26]) hired him to design his estate there.[8] Goad House was featured in Fortune magazine in 1955 (alongside projects of Philip Johnson, Edward Durell Stone, and David Adler) as an example of the first resurgence of Americans “building big expensive houses again” since the Great Depression (with reference to Keyes designing several at the time).[27] Goad House is privately nestled off of evergreen-lined Lone Pine Road, within view of historic Christ Church and down the road from Albert Kahn’s Cranbrook House. The twelve-room house incorporates Keyes’s signature symmetrical bow-fronted wings, clean white brick façade and wrought iron railings, and includes contrasting French shutters and a Palladian, Ionic colonnaded and pedimented front portico with spiral volutes. Fortune said that “Mrs. Goad’s desire for southern-style pillars and white-painted brick was gratified by architect Hugh Keyes. As in many other big houses, the formal living room and dining room are seldom used; the family lives in the library or on the porch (conservatory), usually eats in the breakfast room. The house has an ultra-mechanized kitchen installed by G.M.”[27] The integrated conservatory overlooks the south sloping grounds, with an unusual oval, stone, and “terraced garden and wooded section which lead to a stream,”[28] a tributary of the River Rouge. The exterior of the house was a filming location in the 2013 film The Ides of March, as the senator’s mansion. (Keyes’s McLouth House, a block away, was used as the formal interior of the house in the film.)[29] Goad died in the house in 1979.[30]

Fisher House

Fairway Hills Dr., Franklin (1955)

Client: Max M. Fisher

Fisher House is “a white-brick Georgian with a sprawling garden that borders the eighth fairway of the Franklin Hills Country Club.”[31] The gracious and understated mansion is a fraternal twin to Keyes’s Goad House, from its clean white brick façade to its front pillars, layout and proportions. Over the Tuscan-colonnaded and entablatured front portico is Keyes’s central triangular pediment with ornate cornices. A tall, iron-railed transom window tops the front door. The house’s simple symmetry and proportions are broken up by a large garage to one side. Low lanterned walls of matching construction to the house frame the front of the property. It was built for Max M. Fisher[8] (Forbes 400 member and “oil and real estate magnate”[32]) as his main residence. (Fisher was a very close friend of fellow Keyes-client John Bugas.[33]) The house contains another Keyes-signature “glass-walled garden room” where Fisher conducted his business at home, overlooking the pool and golf course to the south.[31] Fisher was a major supporter of Israel (its “most successful fund raiser” and “the single most important lay person in the American Jewish community”[34]) and close Middle East advisor to Republican Presidents Nixon, Ford, Reagan, G.H.W. Bush, and G.W. Bush[32]—and for many years the estate was guarded by a White House security detail.[31] Fisher died in his house in 2005.[32]

Scherer House

Lake Shore Rd., Grosse Pointe Shores (1951)

Client: Robert Pauli Scherer

Style: Regency

Scherer House is a rambling, split-level design of white brick construction. The house forms a crescent (typical to the Regency style), with a dramatic open floor plan with walls of glass facing Lake St. Clair. In the center of the house is a sweeping staircase and soaring two-story window. The extensive gardens and grounds are elevated and tiered down to the lake. The estate was designed by Keyes for Robert Pauli Scherer.[35] (Scherer—at the age of 24 in 1930—invented the rotary die encapsulation process, which revolutionized the pharmaceutical world and helped raise worldwide health and nutritional standards. He created a multibillion-dollar company around his invention, and his experimental machine ended up in the Smithsonian Institution in 1955.) The house contained a fully equipped metalworking and woodworking shop in the basement.[36] Scherer House was later razed by a new owner—a very rare occurrence for a Keyes house.

Hudson Tannahill House

Lee Gate Ln., Grosse Pointe Farms (1947)

Client: Robert Hudson Tannahill

Hudson Tannahill House is the earliest example of what would become Keyes’s signature distinctive Regency style: white brick construction (with brick pilasters), strong symmetrical façade, a hipped roofline partially concealed by a parapet (giving the appearance of a flat roof), a dormered (garage) wing, and low walls of matching construction. The house has a motor courtyard behind electric gates, and an attached conservatory that overlooks adjacent Lake St. Clair. The estate was built for Robert Hudson Tannahill (a foremost art collector, patron, and scion of J. L. Hudson’s department store fortune[37]). Tannahill had one of the most extensive and “peerless”[1] private late 19th and early 20th-century European art collections in the world. He built his home on Lee Gate Lane specifically to accommodate his sprawling collection—and he looked hard to find an architect to match the quality of his art. (Tannahill and his close first cousin Eleanor Clay Ford, wife of Edsel, had a long relationship with recently deceased Albert Kahn, and Tannahill’s choice of Keyes as next in line to design his home is a testament to Keyes’s standing at the time. Keyes, like Tannahill, nonetheless remains relatively unknown today.)[38] When Tannahill was having the house designed and built in the 1940s, he was becoming increasingly “reclusive and protective of his art.”[39] The house “was like a museum”—though “he seldom showed his collection”—with major works of art as well as many small, elegant pieces. His 5-foot-tall Woman Seated in an Armchair (which he called “the mistress of the house”), as well as a parade of other Picassos, dramatically adorned the house’s stairwell,[37] a Renoir nude adorned the living room, and a Matisse still life hung over the dining room table.[38] “Tannahill was loath to lend art he kept in his home, preferring to be surrounded by their beauty. Still, he enjoyed entertaining friends and family there,” which “evoked the atmosphere of the great French salons.” He donated almost 500 pieces of art to the Detroit Institute of Arts during his life, and upon his death in 1969 he bequeathed another 557 pieces (ranging from Impressionist masterpieces to African miniatures) as well as a large acquisition endowment. (Tannahill’s gifts, valued at around half-a-billion dollars, “have become among the most recognizable and highly prized paintings” in the museum’s world-class collection—all of which he notably restricted from sale and thus protected from creditors.)[38] Tannahill had the house “built like a bunker, meant to stop the spread of fire” in order to protect his art, using “stout walls and ceilings” made of “a lot of cement”[40] (and the parapet exterior wall extending above the roof was commonly used as a fire wall). Ironically, the roof was badly damaged in a fire on November 14, 2014 during renovations by a new owner.[40]

Knudsen Mansion

Bingham Rd., Birmingham (1939)

Client: Semon E. Knudsen

Style: Colonial Georgian

Designed by Keyes for Semon Emil “Bunkie” Knudsen[41] (Executive Vice President of General Motors Company and President of Ford Motor Company), Knudsen Mansion has been described as a “lovely,” “rambling family home,”[42] a “huge mansion,”[43] and “a sprawling, twelve-room colonial farmhouse, with two tennis courts and a swimming pool, on 40 acres in suburban Birmingham, Mich.”[44] Keyes returned again to mixing building materials that he used the previous year at Welch House—in this case using stone gable faces against the house’s brick—as well as retractable fabric awnings framing the windows (a detail Keyes had occasionally used elsewhere, such as on Welch House, Buhs House and Windmill Pointe). White iron rails decorate the upper windows. Keyes connected the main wing and the large garage wing of the asymmetric house with a line of single-story, flat-roofed sun rooms, one with a large circular skylight. The back patio is of brick, framed by low brick walls. Stone pillars (matching the stone of the house) and iron gates mark the entrance to a long winding drive through thick woods (and 24-hour security) that finally ends at the mansion. The estate is the largest of any of Keyes’s projects, as well as the most hidden from view (followed in both cases by Woodland). Upon being fired from Ford in 1971, Knudsen moved to Cleveland and sold his mansion (after subdividing, containing less than half of the original property) two years later to David Hermelin (United States ambassador to Norway and Detroit area philanthropist and entrepreneur[45]), who would have major additions built on the house (including enormous structures which partially overlap Keyes’s original rooflines) and whose widow is still the owner. (Hermelin was known to host major Presidential fund raisers for Bill Clinton at Knudsen Mansion[46]—which is also known as the Hermelin House.)

Welch House

Vaughan Rd., Bloomfield Hills (1938)

Client: Charles G. Welch

Style: Tudor Revival

A block down the leafy, estate-lined road (what Elmore Leonard described in Out of Sight as “Vaughan Road, nothing but money”[47]) from Keyes’s much later Woodland, Welch House is a grand, white brick manor house with a slate roof. Keyes’s Tudor Revival interpretation mixed shingled exterior faces with the brick, and surrounded a main brick-corbelled gable with additional gables to create an asymmetric façade. Retractable fabric awnings originally framed the front windows, overlooking a front yard sloping south down to the slate-roofed, white brick pillars of the front gate. The entranceway is placed at the end of a long drive which circles behind the house to the North. It was built for Charles G. Welch[48] (partner in the eponymous Welch Brothers Motor Car Company, a luxury automobile manufacturer founded by his father in 1904 and acquired by General Motors Company in 1910[49]).

Buhs House

Lochmoor Dr., Grosse Pointe Shores (1936)

Client: Lloyd H. Buhs

Style: International

Buhs House was an extremely innovative home for its day in 1936, called in Architectural Record magazine “an outstanding example of modern architecture. The ‘Made in Detroit’ Home was built and equipped with materials made in Detroit and sponsored by the Detroit Board of Commerce.”[50] Keyes followed much of the International Style of Swiss architect Le Corbusier, and even anticipated the stripped-down Functionalism exemplified in the 1930s in Sweden in Södra Ängby. In Buhs House, Keyes first experimented with a large, clean white brick façade and strict functionalistic themes of cubic volumes, flat-rolled sheet roofs, large windows, and rounded walls and balconies (Le Corbusier’s “ocean liner” aesthetic) that he would gradually morph into his own Regency Moderne style. Keyes designed the home for Lloyd H. Buhs.[51] (The Buhs’s daughter, Martha Henry, became a notable American-Canadian actress. Lloyd Buhs, the secretary-treasurer of the Pfeiffer Brewing Company, was charged in 1943 with embezzling company funds to purchase a controlling interest in a small war plant.[52])

Woodley Green

Lake Shore Dr., Grosse Pointe (1934, 1959)

Clients: Emory W. Clark, Benson Ford

Woodley Green, considered “one of [Keyes’s] finest houses,”[2] is another important work in the Regency and Neo-Palladian style, with a stone pediment front portico with Ionic columns, a parapet and copper hipped roof, and a red brick façade with Keyes’s expected “delicate iron grillwork railings”[5] and symmetrical bow-fronted flanking wings. Overlooking Lake St. Clair at the end of a long, looping gravel driveway “in the midst of beautifully landscaped grounds on Lake Shore Road, it has the appearance of some venerable English country seat”[2] (including its “somewhat disquieting proportions” and “the rather archeological quality of the detail”[53]). Woodley Green was formerly the lakeside estate of Benson Ford (grandson of Henry Ford), for whom Keyes made extensive renovations in 1959.[8] (It is also known as the Emory W. Clark House after the President of the First National Bank of Detroit, for whom it was originally designed by Keyes in 1934.[54])

Other notable works

Schlafer House

Fairway Hills Dr., Franklin (1961)

Client: Maurice A. Schlafer

In 1961, when Keyes was 73, five years after he designed Fisher House on Fairway Hills Dr. in Franklin, Maurice A. Schlafer (of the Schlafer Iron and Metal family[55]) hired him to design a miniature version right across the street.[8] The single story ranch-style house wraps around the back of the property in a U-shape, leaving a deceptively diminutive façade that belies its five-thousand square feet (which still makes it one of the smallest of Keyes’s houses). It has Fisher House’s Regency white brick and Tuscan colonnade and entablature with spiral volutes. Contrasting French shutters frame the walls of windows. Keyes retained his characteristic clean lines, open floor plan, and dramatic light-filled rooms—provided by the maximized window surface area from the back courtyard. Schlafer House would be the last project of Keyes’s career.

Whitby Hall

Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit (1955)

Style: Colonial Georgian

Keyes was chosen by the Detroit Institute of Arts to design the elaborate interior rooms of Whitby Hall, the centerpiece of its American Decorative Arts Gallery. The interiors “were completely redecorated with a new background formed by panelling from Early American Colonial houses. The alterations made to Whitby Hall were quite comprehensive.” New ceilings, fireplaces (including a design with elaborate Doric frieze carving in the parlor[56]), windows, air supply equipment, wiring and lighting “presented a number of problems which were successfully solved.”[57] Whitby Hall was an 18th-century Pennsylvania country house, the farm acquired in 1741 and the house enlarged in 1754 by James Coultas (merchant, shipowner, and high sheriff of Philadelphia from 1755 to 1758).[56] The original house featured a steep pedimented gable with cove cornices, and a three-story, pedimented stone entrance and stair tower.[58] Much of the architectural ornament of Whitby Hall is originally attributed to Samuel Harding (who designed the interior of Independence Hall in 1753, the inspiration for Whitby’s stair tower). The interiors were removed from Whitby Hall in the 1920s and installed at the DIA (where, “ironically, the façade is of white clapboard, a far cry from Whitby’s actual stately gray stone”).[59]

Emory Ford House

Woodland Pl., Grosse Pointe (1949)

Client: Emory M. Ford

Style: Regency

Another renovation and addition by Keyes, the Emory Ford House was originally built in 1928 by Robert O. Derrick. When Emory M. Ford (the great grandson of John Baptiste Ford and part of the “Chemical Ford” family) acquired the estate in 1940, Ford hired Keyes to make significant changes.[51] Keyes added “artistic glass and mirror installations, including a stair banister with glass balusters,”[60] as well as an attached conservatory overlooking Lake St. Clair and a mansard roof with parapet. The house sits just down the road from Keyes’s much earlier mansard house Pingree House.

Tyrol Ski Lodge

Hidden Valley Resort, Gaylord (1947)

Client: Donald B. McLouth

Style: Swiss Chalet

The Hidden Valley Resort was formed in 1937 by Detroit-area steel magnate Donald B. McLouth (founder and president of McLouth Steel) and was the first private ski club in North America[61] (and had the first motorized rope tow in the U.S.[62]). Members included Detroit industrialists such as the families of Henry Ford, William Durant, Walter Briggs, C. Thorne Murphy, Alvan Macauley, David Wallace, Gordon Saunders, and Lang Hubbard.[63] In 1947, 6 years after McLouth hired Keyes to design his home in Bloomfield Hills, Keyes was hired to design an extensive expansion of the resort with a Tyrolian Alpine motif[62] (aided by Austrians in charge of construction and desired by club founders who frequented the slopes of Austria and Switzerland). At the centerpiece of Keyes’s design was a “Hansel-and-Gretel-look” Swiss chalet style lodge,[64] where he incorporated bow-fronted, symmetrical wings and specifically referenced the traditional building style of houses and farms in the Alpine regions of Switzerland, Savoy and Tyrol. (Keyes’s designs subsequently inspired an alpine theme throughout the nearby village of Gaylord.[64]) The lodge’s “original caramel-stained pine logs, accented with Bavarian-blue trim, are retained today.”[62]

McLouth House

Martell Dr., Bloomfield Hills (1941)

Client: Donald B. McLouth

Designed by Keyes for Donald B. McLouth (of McLouth Steel) in 1941,[65] McLouth House was in many ways a precursor to Goad House and Fisher House, both built in 1955; McLouth House was Keyes’s initial use of many of the forms used in these much later projects, such as an ornately-corniced triangular pediment, Tuscan-colonnaded and entablatured front portico, attached conservatory, curved, pilastered brick walls framing the property, and double-story patios in back (almost identical to that of Fisher House). Keyes used what was becoming his signature clean white brick construction. (McLouth House and Goad House were both filming locations in the 2013 film The Ides of March.[29]) McLouth would later again hire Keyes for his summer home and private wilderness club Green Timbers, as well as for the Tyrol Ski Lodge at his Hidden Valley Resort. (McLouth House is also known as the Caldwell House, after its subsequent owner Philip Caldwell, the successor to Henry Ford II as Chairman and CEO of Ford Motor Company.[66])

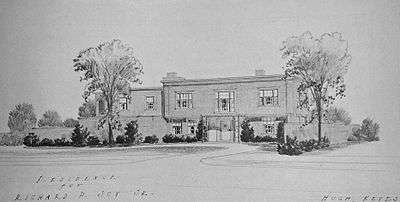

Joy House

Renaud Rd., Grosse Pointe Shores (1938)

Client: Richard P. Joy, Jr.

Style: Regency

Joy House is another of Keyes’s flat-roof designs with ornate double-cornices and white brick construction, and evolved into his Regency style with a colonnaded front portico and delicate iron gates and railings. Joy House also has an early example of what would become Keyes’s signature large central transom window. A gabled roof was later built atop the original flat roof (though not by Keyes). (Richard Joy, Jr., for whom Keyes designed the house, hails from the Joy dynasty, his grandfather James F. Joy a railroad magnate and “one of the foremost business men of the U.S.” and his father Richard P. Joy the President of the National Bank of Commerce and a Director of the Packard Motor Car Company—where his brother Henry B. Joy was also President and a major investor—among other companies.[67] Records of Richard Jr. mention him only as a “yachtsman”—the Joy family were long time New York Yacht Club members.)

Lake Park House

Lake Park Rd., Bloomfield Hills (1937)

Client: Max M. Gilman

Keyes designed Lake Park House for Max M. Gilman[51] (President of the Packard Motor Car Company). His “huge house in Bloomfield Hills”[68] represented a departure from the huge baronial houses in Grosse Pointe, such as that of Gilman’s long time predecessor Alvan Macauley (whose son Edward also owned a Keyes Grosse Pointe house[24]). Keyes continued his large white brick façade, accented with French shutters, a unique colonnaded copper front portico, and a steep, hipped roof broken up with curved dormers. In the back, copper awnings frame the windows, a two-story windowed vestibule with more columns overlooks the sloping garden, and a lower wing extends to the side (which was later removed when the large estate was subdivided) where an iron-railed patio is concealed above an open garden conservatory. The wooded end of the garden rolls sharply down to an inland lake (Quarton Lake, along the same tributary as Goad House).

Hudson House

Lothrop Rd., Grosse Pointe Farms (1937)

Client: J. Stewart Hudson

Hudson House is one of several Regency style houses built by Keyes in Grosse Pointe in the thirties containing many Neo-Palladian and Jeffersonian (sometimes labeled as Georgian) architectural details. The broad, imposing red brick mansion has symmetrical wings flanking a central triangular pediment tympanum with circular stone relief, an Ionic-columned stone portico, arched brickwork, and a flat, parapet roof. An iron fence frames a circular drive in the front and intricate gardens and fountains in the back. The interior features arched doorways, a loggia and two-story sweeping staircase. The estate was built for Doctor J. Stewart Hudson.

Trix House

Fisher Rd. (formerly E. Jefferson Ave.), Grosse Pointe (1937)

Client: Herbert B. Trix

Style: Regency, International

Designed right after Buhs House, Keyes continued his International/Functionalism Style in Trix House, with a simple flat roof, white brick construction, large windows and rounded walls—though with an increasingly distinctive Regency flair with ornate double-cornices and contrasting French shutters. Its otherwise very cubic volumes are broken up by a curved entranceway that leads to a side garage wing with attached greenhouse. The estate originally had an E. Jefferson avenue address, until the large lot was subdivided and the house used a new facing side road as its address. The house was built for Herbert B. Trix, President of automotive supplier American Injector Company, Director of several banks, one-time mayor of Grosse Pointe,[69] and, at forty, the youngest president in the Detroit Athletic Club’s history.[70]

Pingree House

Woodland Pl., Grosse Pointe (1935)

Clients: Hazen Pingree family

Style: Second Empire

Pingree House was built in 1909 (the first house ever built on once heavily wooded Woodland Place on Lake St. Clair—now a suburban cul-de-sac) as the summer home of the Hazen S. Pingree family.[71] (Pingree was a four-term mayor of Detroit and Governor of Michigan.) The original small house was built in a whimsical Dutch Colonial style with gambrel roof and flared eaves, designed by William Stratton (who built a similar gambrel-roofed, “low, one-and-a-half story English farm house” the same year a block away for Frederick M. Alger[9]). In 1935, the Pingrees hired Keyes to design extensive additions to their home (as he had done in 1925 for William Pickett Harris), tripling its original size in order to turn it into a year-round residence. Keyes retained the same brick construction (including in the new carriage house), and created several bow-fronted wings of additions that wrap around the original structure. Keyes blended a new mansard roofline with the original similar gambrel roof, giving the expanded house a more French (Second Empire) style. (Keyes borrows from Robert O. Derrick’s 1926 design of nearby Edwin H. Brown House, “striking a note of restrained yet charmingly intimate French Classicism with its Mansard roof.”[9]) Pingree House is significant in that it marked the beginning of Keyes’s more restrained and increasingly French-influenced Regency style, and it was his first use of the mansard roof that would be a prominent feature in what he considered one of his greatest designs—Woodland. Descendants of the Pingrees lived in the home until 1976.[71] (It is also known as the Parker/Mills House.)

The Acorns

Metamora (1931)

Client: Gail Stephens Kinard

Style: Log Lodge, Swiss Chalet

Gail Stephens (Kinard), a “wealthy Detroit sportswoman”[72] whose father was lumber baron Henry Stephens,[73] hired Keyes[51] to build “a magnificent lodge named ‘The Acorns’ in the quiescent hills of Metamora, far from the hustle and bustle of the motor city.”[74] Described as a “costly Norwegian hunting lodge,”[72] “an elaborate rural retreat”[74] and a “palatial country estate,”[73] the building is constructed of large logs on the main floor and timber framing with board-and-batten exterior on the upper floor. Ornate murals reference the 19th-century Great Camps and Swiss chalet style of architecture. A massive stone fireplace has an inscription that reads: “They say— What do they say? Who cares what they say?”[74] (Gail Stephens Kinard achieved much notoriety when she reunited with her childhood sweetheart, Dr. Kerwin Kinard, whom she first met as a student in Berlin and hadn’t seen for twenty-five years, and suddenly married shortly thereafter—for which she was served a one-million dollar “alienation of affections” suit in 1932 from Dr. Kinard’s estranged wife, and was “dropped from Detroit's social register of 1933.”[72])

Mennen Hall

Provençal Rd., Grosse Pointe Farms (1929)

Clients: Henry P. Williams, Elma C. Mennen

Style: Tudor Revival

Arched chimney caps dot the roofline of Keyes’s stately brick Tudor, Mennen Hall, that sits along a private, guarded road. It was built for (real estate tycoon) Henry P. Williams and his wife Elma C. Mennen (heiress to the Mennen personal grooming products fortune), whose eldest son was G. Mennen “Soapy” Williams (a six-term Governor of Michigan and Chief Justice of the Michigan Supreme Court).[75]

Dwyer/Palms House

Lake Shore Rd., Grosse Pointe Farms (1928)

Client: Marie Fleitz Dwyer

Style: French Normandy

Built “in the late 20’s, when cost was of little or no consideration,”[10] for Marie Fleitz Dwyer, the widowed daughter of a Michigan lumber baron and grain merchant, the French Normandy style house was the first in the area wired for telephones (and, until recently, there was a circuit panel in the garage through which all the neighborhood phones were wired). The house was made from limestone and the roof from slate with a copper flat top, and an intricate stone-carved pediment frames the front door. The house contains “a step-down living room, a sweeping staircase, curved hallways,” and numerous fireplaces.[76] (Keyes designed a smaller version of the Dwyer/Palms House the same year on Kenwood Rd. in Grosse Pointe Farms.) The estate’s “impeccable grounds”[76] back onto Lake St. Clair, originally with a dock extending over 100 feet into the lake. The house and grounds have been the filming location for several movies.

Keane House

Lakeland St., Grosse Pointe (1926)

Client: Jerome E. Keane

Style: Tudor Revival

Built for (investment banker) Jerome E. Keane,[51] Keane House is a large Tudor of red brick and half-timbering. The design included Keyes’s first use of a massive wall with slate-roofed pillars surrounding the estate, which matches and is incorporated into the brick façade of the house—an often-repeated motif later in his career. Multiple gables with intricate brick corbelling are a new Keyes motif (that he would use again and again, for example in 1928 in the Stoepel House on Touraine Road in Grosse Pointe Farms and later at Welch House and Woodland on Vaughan Road in Bloomfield Hills).

Windmill Pointe

Windmill Pointe Dr., Grosse Pointe (1925)

Client: William Pickett Harris

Style: Tudor Revival

The “sprawling palace on Windmill Pointe with its groomed grounds, coffered ceilings and limestone arches” was originally designed by New York model farm architect Alfred Hopkins[77][78] in an extravagant Tudor style[2] for William Pickett Harris (an investment banker, expert on squirrels, and curator of mammals at the Museum of Zoology of the University of Michigan[79]). Just four years after the house’s completion, Keyes was hired to double its original size in order to accommodate Harris’s growing family[78]—which included his daughter Julie Harris[77] (the stage, screen, and television actress—“the most decorated performer in the history of Broadway”[79]). Keyes incorporated original architectural details, windows and doors into his outward and upward expansion. Among this expansion were additional bedrooms, including a master bedroom on the main floor (“a rare setup for a home built in the 1920s”[78]—and one Keyes would later adopt in many other projects). But of most significance was Keyes’s lower level recreation room and wine cellar along with a sunken rock garden. As American Home magazine described its innovative design in 1934:

| “ | Keyes encountered a problem in plans for the recreation room. The only available space for this purpose was in the basement, but Mr. Harris wanted plenty of sunlight there, particularly on account of the children, who were expected to use it a great deal during the day. There really was nothing that could be done to meet requirements but clear the soil away from the wall on the outside and install a bank of windows. This was done, and the rock garden idea unfolded as a sequence. Within the recreation room the greatest delight comes from the practical treatment of the windows, which are of full size and afford a wide sweep of vision out and across the lawn. The feeling that one is in a basement seems to be entirely absent. The room has been treated in a playful, rustic manner. The rich, tawny color of the Norway pine logs furnishes a substantial and cheerful background for the showy reds and blues of the chairs, rugs, and curtains. So delightful were the results of this simple stroke of architecture that the recreation room has become the favorite retreat both day and evening for every member of the family. There is a big stone fireplace where crackling logs throw out warmth in the winter months, vying with the low winter sun which pours its radiance through the bank of windows. In the summertime it is the coolest place in the house, ventilated by eddies caught in the rock garden basin. No other room possesses more varied interests or enticing environments.[80] | ” |

Ridgeland

Lewiston Rd., Grosse Pointe (1924)

Client: Charles A. Dean

Style: Italianate

On a sloping ridge surrounded by giant oak trees lies Ridgeland, a rambling country villa in the Italianate style made of tawny bricks (rather than Italian stucco). “Designed by Keyes during the height of the roaring twenties, it provided a dramatic setting for large parties the wealthy Charles Dean (its original owner) was famous for hosting.”[81] The house informally sprawls backward asymmetrically down the hillside, folding back on itself so that “the house becomes part of the view from its own windows.” With its expansive brick walls, outbuildings, and potting shed, “the house feels like its own enclosed community.”[82] (It is thought that a secret underground passageway exists from the main house to the garage.) The variously scaled rooms open up through French doors to slate patios, intimate gardens and stretches of lawn.[9] Ridgeland’s Italianate style is Keyes’s first significant experiment with Palladianism, synthesized with picturesque aesthetics: low-pitched and hipped tile roofs, stained glass windows, arched doors and ceilings, loggias and balconies with wrought iron railings, a tower, and walls and beams painted with elaborate 14th-century Florentine motifs. (Ridgeland is also known as the Charles A. Dean House.)

References

- 1 2 "The Automaker's Surprising Aesthetic Legacy in Michigan". Architectural Digest. July 1, 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ferry, W. Hawkins (1968). The Buildings of Detroit. Wayne State University Press.

- ↑ "Four Architects Honored". The Harvard Crimson. March 28, 1914.

- 1 2 3 American Architects Directory. R.R. Bowker (American Institute of Architects). First edition, 1956.

- 1 2 Woodford, Arthur (2015). The Village of Grosse Pointe Shores. Arcadia Publishing.

- ↑ Hildebrand, Grant (1980). Designing for Industry: The Architecture of Albert Kahn. MIT Press.

- ↑ Matuz, Roger (2002). Albert Kahn: Builder of Detroit. Wayne State University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 American Architects Directory. R.R. Bowker (American Institute of Architects). Second edition, 1962.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ferry, W. Hawkins (1956). A Suburb In Good Taste. Michigan Society of Architects.

- 1 2 "An Outstanding Lakefront Home in The Farms". Grosse Pointe News. August 8, 1968.

- ↑ The New International Year Book. Dodd, Mead and Company. 1989.

- ↑ Kvaran & Lockey, A Field Guide to Architectural Sculpture in America, unpublished manuscript

- ↑ Cranbrook Institute of Science Annual Report, Volumes 1-11. 1930.

- ↑ F&ES working paper, Issues 7-10. Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. 1978.

- 1 2 3 4 "Passion Makes Perfect: The Voluptuous World of Linda and Robert Taubman". Vogue. November 1, 1986.

- ↑ teNeues (2008). Luxury Private Gardens. teNeues.

- 1 2 3 Tasma-Anargyros, Sophie (1997). Andrée Putman. Overlook Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Salny, Stephen M. (2014). William Hodgins Interiors. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Katia Hetter (February 18, 2013). "'Downton' in America: 6 big estates". CNN.

- ↑ Paul Goldberger (April 8, 1984). "The Cranbrook Vision". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 "Seaside Chic in Belgium". Architectural Digest. March 1, 1999.

- ↑ "Andree Putman's Sought-After Style". The New York Times. July 17, 1986.

- ↑ "AD100 Hall of Famer's great white ways". Architectural Digest. October 1, 2013.

- 1 2 Michigan Historical Collections. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved on February 3, 2013.

- ↑ UPI (December 3, 1982). "John S. Bugas is Dead at 74; Was Top Executive at Ford". The New York Times.

- ↑ "PERSONNEL: No. 3 Man at G.M.". Time. September 14, 1959.

- 1 2 "The $250,000 House". Fortune. October 1, 1955.

- ↑ "Garden Pilgrimage at the L.C. Goad residence". The Birminghan Eccentric. May 17, 1956.

- 1 2 Complete list of filming locations for George Clooney’s ‘Ides of March’. OLV. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Louis Clifford Goad, 78, Is Dead; Engineer and Executive for G.M.; General Manager in 1938". The New York Times. November 17, 1979.

- 1 2 3 Golden, Peter (1992). Quiet Diplomat: A Biography of Max M. Fisher. Cornwall Books / Herzl Press.

- 1 2 3 AP (March 4, 2005). "Max Fisher, 96, Philanthropist and Adviser to Presidents, Dies". The New York Times.

- ↑ At John Bugas’ Ranch. The Max M. Fisher Archives. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ Javits, Jacob K. (1981). Javits: The Autobiography of a Public Man. Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ Leonard, John W. (1959). Who’s who in Engineering. John W. Leonard Corporation.

- ↑ "Robert Pauli Scherer". Heritage. November 1, 1986.

- 1 2 "Portrait of a Collector: Robert Hudson Tannahill's bequest left the DIA a priceless visual legacy". Hour Detroit. August 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Fords have company among DIA's greatest patrons". The Detroit News. August 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Collective vision". The Washington Times. September 23, 2000.

- 1 2 "Fire plays hard to get". Grosse Pointe News. November 20, 2014.

- ↑ The Social Secretary of Detroit. 1958.

- ↑ "Knudsen Views His Ford Job as Challenge—to Help People". Chicago Tribune. February 11, 1968.

- ↑ "Semon E. (Bunkie) Knudsen's huge mansion". Ward's Auto World, Volume 8, Issues 7-12. 1972.

- ↑ "Automaker Knudsen". Time, Volume 73. 1959.

- ↑ "David Hermelin, 63, a Diplomat Who Artfully Used the Hot Dog". The New York Times. November 23, 2000.

- ↑ "Clinton Raises Big Bucks on Michigan Trip". AP News. March 5, 1996.

- ↑ Leonard, Elmore (1996). Out of Sight. Delacorte Press.

- ↑ Searcy, Virginia F. (1947). The Official Michigan Social Register.

- ↑ Kimes, Beverly Rae (1996). Standard Catalog of American Cars, 1805-1942. Krause Publications.

- ↑ "In keeping with the TEMPO of Modern architecture". Architectural Record, Volume 80, Issue 6. 1936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michigan Historical Collections. Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved on February 3, 2013.

- ↑ . The Daily Telegram. November 20, 1943. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Woodford, Arthur (1994). Tonnancour: Life in Grosse Pointe and Along the Shores of Lake St. Clair, Volume 1. Omnigraphics.

- ↑ Meyer, Katherine Mattingly and Martin C.P. McElroy with Introduction by W. Hawkins Ferry (1980). Detroit Architecture A.I.A. Guide Revised Edition. Wayne State University Press.

- ↑ Michigan Manufacturer and Financial Record, Volume 74. Pick Publications. 1944.

- 1 2 Heckscher, Morrison H. (1992). American Rococo, 1750-1775: Elegance in Ornament. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Bulletin. The Detroit Institute of Arts. Volume XXXV, No. 2, 1955-56. Retrieved on November 15, 2014.

- ↑ Kornwolf, James D. (2002). Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ↑ "This piece of history keeps changing". The Philadelphia Inquirer. September 6, 1992.

- ↑ "Three houses honored". Grosse Pointe News. June 11, 2009.

- ↑ "Peaks and Valleys". dbusiness. September 2009.

- 1 2 3 "That Special Feeling" (PDF). Heritage: A Journal of Grosse Pointe Life. December 1987.

- ↑ Eckert, Kathryn Bishop, ‘’Buildings of Michigan’’. Oxford University Press, New York, 1993. p 440

- 1 2 "Key impetus for Alpine Village theme". Herald Times. 1989-03-09.

- ↑ The Social Secretary of Detroit. 1948.

- ↑ The Social Secretary of Detroit. 1978.

- ↑ Michigan. The Lewis Publishing Company. 1915.

- ↑ Ward, James Arthur (1995). The Fall of the Packard Motor Car Company. Stanford University Press.

- ↑ The Michigan Alumnus, Volume 44. UM Libraries. 1937.

- ↑ Voyles, Kenneth H. (2012). The Enduring Legacy of the Detroit Athletic Club. The History Press.

- 1 2 "Historical Society honors 4 local sites with markers". Grosse Pointe News. April 30, 1992.

- 1 2 3 "Mrs. Gail Stephens Kinard, wealthy Detroit sportswoman, has been dropped from Detroit's social register of 1933". The Kansas City Star. February 11, 1933.

- 1 2 "Decline to Discuss Heart Balm Suit". The Sedalia Democrat. December 7, 1932.

- 1 2 3 "The $1,000,000 Love-Claim Kickback to a Lavender-and-Old-Lace Romance". The Spokesman Review. January 21, 1933.

- ↑ Burton, Clarence M. (1922). The City of Detroit Michigan 1701-1922.

- 1 2 "2010 show house a spectacle near lake". Detroit Free Press. May 6, 2010.

- 1 2 "Michigan House Envy: Windmill Pointe palace offers medieval charm". Detroit Free Press. November 4, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "An English Manor in Michigan". The Wall Street Journal. April 22, 2015.

- 1 2 Bruce Weber (August 24, 2013). "Julie Harris, Celebrated Actress of Range and Intensity, Dies at 87". The New York Times.

- ↑ "A sunny basement recreation room". American Home, Volume 13. 1934.

- ↑ "An architects' tour of five Pointe" (PDF). Grosse Pointe News. September 11, 1980.

- ↑ "Grosse Pointe villa offers a taste of Tuscany". Detroit Free Press. May 11, 2014.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hugh T. Keyes. |