Initiatives and referendums in the United States

Initiative, referendum, and recall are three powers reserved to enable the voters, by petition, to propose or repeal legislation or to remove an elected official from office. Proponents of an initiative, referendum, or recall effort must apply for an official petition serial number from the Town Clerk. (EKS).

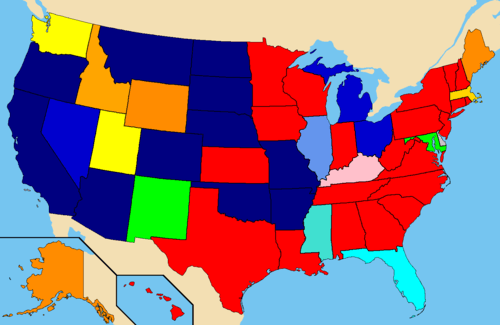

In the politics of the United States, the process of initiatives and referendums allow citizens of many U.S. states[1] to place new legislation on a popular ballot, or to place legislation that has recently been passed by a legislature on a ballot for a popular vote. Initiatives and referendums, along with recall elections and popular primary elections, are signature reforms of the Progressive Era; and they are written into several state constitutions, particularly in the West.

History

Initiative, referendum, and recall are three powers reserved to enable the voters, by petition, to propose or repeal legislation or to remove an elected official from office. Proponents of an initiative, referendum, or recall effort must apply for an official petition serial number from the Town Clerk. (EKS).

The Progressive Era was a period marked by reforms aimed at breaking the concentrated, some would say monopoly, power of certain corporations and trusts. Many Progressives believed that state legislatures were part of this problem and that they were essentially "in the pocket" of certain wealthy interests. They sought a method to counter this—a way in which average persons could become directly involved in the political process. One of the methods they came up with was the initiative and referendum. Between 1904 and 2007, some 2231 statewide referendums initiated by citizens were held in the USA. 909 of these initiatives have been approved. Perhaps even greater is the number of such referendums that have been called by state legislatures or mandatory—600 compared to 311 civic initiatives in 2000-2007.

Types of initiatives and referendums

Initiatives and referendums—collectively known as "ballot measures," "propositions," or simply "questions"—differ from most legislation passed by representative democracies; ordinarily, an elected legislative body develops and passes laws. Initiatives and referendums, by contrast, allow citizens to vote directly on legislation.

In many U.S. states, ballot measures may originate by several different processes:[2] Overall, 27 US states and Washington D.C. allow some form of direct democracy.

Initiatives

- An Initiative is a means through which any citizen or organization may gather a predetermined number of signatures to qualify a measure to be placed on a ballot, and to be voted upon in a future election. (These may be further divided into constitutional amendments and statutory initiatives. Statutory initiatives typically require fewer signatures to qualify to be placed on a future ballot.)

Initiated state statute

The following US states allow initiated state statutes, also called initiative (direct) state statutes:

- Arizona

Indirect initiative state statute

The following US states allow legislatively-referred state statutes:

- Maine

- Massachusetts (proper term is initiative petition, for all forms of referendum voting)

- Michigan

- Nevada

- Ohio

- Utah

- Washington

- Wyoming

While the following US states allow legislative action to void a petition:

- Alaska See, AS15.45.190 and AS15.45.210

Indirect initiated state constitutional amendment

The initiative process, for proposing constitutional amendments, may be "direct" or "indirect". States that permit indirect constitutional amendments, like Mississippi, permit legislators to propose an alternative amendment which is placed on the ballot alongside the direct citizen proposal.[3]

The following US states allow indirect initiated state constitutional amendments:

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

Initiated state constitutional amendment

An initiated constitutional amendment is an amendment to a state's constitution that results from petitioning by a state's citizens. By utilizing this initiative process, citizens can propose and vote on constitutional amendments directly, without need of legislative referral. When a sufficient number of citizens have signed a petition requesting it, a proposed constitutional amendment is then put to the vote.

In the United States, while no court or legislature needs to approve a proposal or the resultant initiated constitutional amendment, such amendments may be overturned if they are challenged and a court confirms that they are unconstitutional.[4] Most states that permit the process require a 2/3 majority vote.[4]

Not all amendments proposed will receive sufficient support to be placed on the ballot. Of the 26 proposed petitions filed in the state of Florida in its 1994 general election, only three garnered sufficient support to be put to the vote.[5]

The following US states allow initiated (direct) state constitutional amendments:

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Florida

- Illinois

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- South Dakota

Referendum

- Popular Referendum, in which a predetermined number of signatures (typically lower than the number required for an initiative) qualifies a ballot measure for repealing a specific act of the legislature.

The following US states allow referendum:

- Alaska

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Delaware

- Idaho

- Illinois

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Mexico

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- South Dakota

- Utah

- Washington

Legislative referral

- Legislative referral (aka "legislative referendum"), in which the legislature puts proposed legislation up for popular vote (either voluntarily or, in the case of a constitutional amendment, as a necessary part of the procedure.)

Legislatively-referred state statute

Legislatively-referred state statute

The following US states allow legislatively-referred state statutes:

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- Colorado

- Delaware

- Illinois

- Kentucky

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- South Dakota

- Texas

- Utah

- Washington

Legislatively-referred state constitutional amendment

Legislatively-referred state constitutional amendment

With the exception of Delaware, 49 US states allow legislatively-referred state constitutional amendments.

Objections to the system

The initiative and referendums process have critics. Some argue that initiatives and referendums undermine representative government by circumventing the elected representatives of the people and allowing the people to directly make policy: they fear excessive majoritarianism (tyranny of the majority) as a result, believing that minority groups may be harmed.[6][7][8]

Other criticisms are that competing initiatives with conflicting provisions can create legal difficulties when both pass;[9] and that when the initiatives are proposed before the end of the legislative session, the legislature can make statutory changes that weaken the case for passing the initiative.[10] Yet another criticism is that as the number of required signatures has risen in tandem with populations, "initiatives have moved away from empowering the average citizen" and toward becoming a tool for well-heeled special interests to advance their agendas.[11] John Diaz wrote in an editorial for the San Francisco Chronicle in 2008:[12]

| “ | There is no big secret to the formula for manipulating California's initiative process. Find a billionaire benefactor with the ideological motivation or crass self-interest to spend the $1-million plus to get something on the ballot with mercenary signature gatherers. Stretch as far as required to link it to the issue of the ages (this is for the children, Prop. 3) or the cause of the day (this is about energy independence and renewable resources, Props. 7 and 10). If it's a tough sell on the facts, give it a sympathetic face and name such as "Marsy's Law" (Prop. 9, victims' rights and parole) or "Sarah's Law" (Prop. 4, parental notification on abortion). Prepare to spend a bundle on soft-focus television advertising and hope voters don't notice the fine print or the independent analyses of good-government groups or newspaper editorial boards...Today, the initiative process is no longer the antidote to special interests and the moneyed class; it is their vehicle of choice to attempt to get their way without having to endure the scrutiny and compromise of the legislative process. | ” |

In some cases, voters have passed initiatives that were subsequently repealed or drastically changed by the legislature. For instance, legislation passed by the voters as an Arizonan medical cannabis initiative was subsequently gutted by the Arizona legislature.[13] To prevent such occurrences, initiatives are sometimes used to amend the state constitution and thus prevent the legislature from changing it without sending a referendum to the voters; however, this produces the problems of inflexibility mentioned above. Accordingly, some states are seeking a middle route. For example, Colorado's Referendum O would require a two-thirds vote for the legislature to change statutes passed by the voters through initiatives, until five years after such passage. This would allow the legislature to easily make uncontroversial changes.[14]

An objection not so much to the initiative concept, but to its present implementations, is that signature challenges are becoming a political tool, with state officials and opposing groups litigating the process, rather than simply taking the issue fight to voters.[15] Signatures can be declared void based on technical omissions, and initiatives can be thrown out based on statistical samplings of signatures. Supporters lacking necessary funds to sustain legal battles can find their initiative taken off the ballot.

Proposed reforms

Some proposed reforms include paying signature gatherers by the hour, rather than by the signature (to reduce incentives for fraud) and increasing transparency by requiring major financial backers of initiatives to be disclosed to potential signatories. Other proposals include having a "cooling-off" period after an initiative qualifies, in which the legislature can make the initiative unnecessary by passing legislation acceptable to the initiative's sponsors.[16] It has also been proposed that proxy voting be combined with initiative and referendum to form a hybrid of direct democracy and representative democracy.[17]

National initiative

The national initiative is a proposal to amend the United States Constitution to allow ballot initiatives at the federal level.

Citizens' Initiative Review

Healthy Democracy, and a similar organization in Washington State, proposed a Citizens' Initiative Review process. This brings together a representative cross-section of voters as a citizens' jury to question and hear from advocates and experts regarding a ballot measure; then deliberate and reflect together to come up with statements that support and/or oppose the measure. The state would organize such a review of each ballot measure, and include the panelists' statements in the voters' pamphlet. Since 2009, Healthy Democracy has led efforts to develop and refine the Citizens’ Initiative Review process for use by Oregon voters .

In 2011, the Oregon Legislature approved House Bill 2634, legislation making the Citizens’ Initiative Review a permanent part of Oregon elections.[18] This marked the first time a legislature has made voter deliberation a formalized part of the election process. The CIR is a benchmark in the initiative reform and public engagement fields.

Each state has individual requirements to qualify initiatives for the ballot. Generally, all 24 states and the District of Columbia follow steps similar to:

- File a proposed petition with a designated state official

- State review of the proposal and, in several states, a review of the language of the proposal

- Prepare ballot title and summary

- Petition circulation to obtain the required number of signatures

- Petition submitted to state election officials to verify the signatures and qualify the ballot entry

See also

References

- ↑ "State by state listing of where they are used". Iandrinstitute.org. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "What is I&R?". Iandrinstitute.org. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "Constitutional Initiative in Mississippi: A Citizen's Guide" (PDF). Secretary of State, Mississippi. 2009-01-14. p. 2. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- 1 2 Mason, Colin (October 2003). The 2030 Spike: Countdown to Global Catastrophe. Earthscan. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-84407-018-3. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ Jameson, P.K. and Marsha Hosack. (1996) "Citizen Initiative in Florida: An Analysis of Florida's Constitutional Initiative Process, Issues, and Statutory Initiative Alternatives." pp. 1-2. Originally published in Florida State University Law Review 23:417.

- ↑ Gamble, Barbara S. (1997). "Putting Civil Rights to a Popular Vote". American Journal of Political Science. 41 (1): 245–269. doi:10.2307/2111715. JSTOR 2111715.

- ↑ Hajnal, Zoltan; Gerber, Elisabeth R.; Louch, Hugh (2002). "Minorities and Direct Legislation: Evidence from California Ballot Proposition Elections". Journal of Politics. 64: 154–177. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00122.

- ↑ Gray, Virginia & Russell L. Hanson. Politics in the American States. 9 ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2008. p. 141.

- ↑ "Was the Price Too High for Colorado Initiative Deal? - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. 2008-10-13. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑

- ↑ "Vote NO on Prop 105 » In The News". Thevotersofaz.com. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ John Diaz (2008-10-12). "A long way from the grassroots". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Golden, Tim (1997-04-17). "Medical Use of Marijuana To Stay Illegal in Arizona - NYTimes.com". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ "The Pueblo Chieftain Online :: Referendum O limits constitutional changes". Chieftain.com. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ http://www.mansfieldnewsjournal.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20081018/UPDATES01/81018012. Retrieved October 20, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/op/OP_1100FSOP.pdf

- ↑ http://larson2008.com/wiki/index.php5?title=Proxy_voting. Retrieved October 21, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.oregon.gov/circ/Pages/index.aspx

External links

- Portal: Ballot measures at Ballotpedia

- Citizens in Charge

- NCSL Ballot Measures Database

- NCSL Initiative & Referendum Legislation Database

- The National Initiative for Democracy (NI4D)

- The National Initiative for Democracy

- The Initiative and Referendum and how Oregon got them, by Burton J. Hendrick