Ship stability

Ship stability is an area of naval architecture and ship design that deals with how a ship behaves at sea, both in still water and in waves, whether intact or damaged. Stability calculations focus on the center of gravity, center of buoyancy, and metacenter of vessels and on how these interact.

History

Ship stability, as it pertains to naval architecture, has been taken into account for hundreds of years. Historically, ship stability calculations for ships relied on rule of thumb calculations, often tied to a specific system of measurement. Some of these very old equations continue to be used in naval architecture books today. However, the advent of calculus-based methods of determining stability, particularly Pierre Bouguer's introduction of the concept of the metacenter in the 1740'S ship model basin allows much more complex analysis.

Master shipbuilders of the past used a system of adaptive and variant design. Ships were often copied from one generation to the next with only minor changes being made; by replicating a stable design serious problems were not often encountered. Ships today still use the process of adaptation and variation that has been used for hundreds of years; however computational fluid dynamics, ship model testing and a better overall understanding of fluid and ship motions has allowed much more analytical design.

Transverse and longitudinal waterproof bulkheads were introduced in ironclad designs between 1860 and the 1880s, anti-collision bulkheads having been made compulsory in British steam merchant ships prior to 1860.[1] Before this a hull breach in any part of a vessel could flood the entire length of the ship. Transverse bulkheads, while expensive, increase the likelihood of ship survival in the event of damage to the hull, by limiting flooding to breached compartments separated by bulkheads from undamaged ones. Longitudinal bulkheads have a similar purpose, but damaged stability effects must be taken into account to eliminate excessive heeling. Today, most ships have means to equalize the water in sections port and starboard (cross flooding), which helps to limit the stresses experienced by the structure and also to alter the heel and/or trim of the ship.

Add-on stability systems

These systems are designed to reduce the effects of waves or wind gusts. They do not increase the stability of the vessel in a calm sea. The International Maritime Organization International Convention on Load Lines does not mention active stability systems as a method of ensuring stability. The hull must be stable without active systems.

Passive systems

Bilge keel

A bilge keel is a long fin of metal, often in a "V" shape, welded along the length of the ship at the turn of the bilge. Bilge keels are employed in pairs (one for each side of the ship). A ship may have more than one bilge keel per side, but this is rare. Bilge keels increase the hydrodynamic resistance when a vessel rolls, thus limiting the amount of roll a vessel has to endure.

Outriggers

Outriggers may be employed on certain vessels to reduce rolling. Rolling is reduced either by the force required to submerge buoyant floats or by hydrodynamic foils. In some cases these outriggers may be of sufficient size to classify the vessel as a trimaran; however on other vessels they may simply be referred to as stabilizers.

Antiroll tanks

Antiroll tanks are tanks within the vessel fitted with baffles intended to slow the rate of water transfer from the port side of the tank to the starboard side. The tank is designed such that a larger amount of water is trapped on the higher side of the vessel. This is intended to have an effect completely opposite to that of the free surface effect.

Paravanes

Paravanes may be employed by slow-moving vessels (such as fishing vessels) to reduce roll.

Active systems

Many vessels are fitted with active stability systems. Active stability systems are defined by the need to input energy to the system in the form of a pump, hydraulic piston, or electric actuator. These systems include stabilizer fins attached to the side of the vessel or tanks in which fluid is pumped around to counteract the motion of the vessel.

Stabilizer fins

Active fin stabilizers are normally used to reduce the roll that a vessel experiences while underway or, more recently, while at rest. The fins extend beyond the hull of the vessel below the waterline and alter their angle of attack depending upon heel angle and rate-of-roll of the vessel. They operate similar to airplane ailerons. Cruise ships and yachts frequently use this type of stabilizer system.

When fins are not retractable, they constitute fixed appendages to the hull, possibly extending the beam or draft envelope, requiring attention for additional hull clearances.

While the typical "active fin" stabilizer will effectively counteract roll for ships underway, some modern active fin systems have been shown capable of reducing roll motion when vessels are not underway. Referred to as zero-speed or Stabilization at Rest, these systems work by moving fins of special design, with the requisite acceleration and impulse timing to create effective roll cancellation energy.

Gyroscopic internal stabilizers

Gyroscopes were first used to control a ship's roll in the late 1920s and early 1930s for warships and then passenger liners. The most ambitious use of large gyros to control a ship's roll was on an Italian passenger liner, the SS Conte di Savoia, in which three large Sperry gyros were mounted in the forward part of the ship. While it proved successful in drastically reducing roll in the westbound trips, the system had to be disconnected on the eastbound leg for safety reasons. This was because with a following sea (and the deep slow rolls this generated) the vessel tended to 'hang' with the system turned on, and the inertia it generated made it harder for the vessel to right herself from heavy rolls. [2]

Gyro stabilizers consist of a spinning flywheel and gyroscopic precession that imposes boat-righting torque on the hull structure. The angular momentum of the gyro’s flywheel is a measure of the extent to which the flywheel will continue to rotate about its axis unless acted upon by an external torque. The higher the angular momentum, the greater the resisting force of the gyro to external torque (in this case more ability to cancel boat roll).

A gyroscope has three axes: a spin axis, an input axis, and an output axis. The spin axis is the axis about which the flywheel is spinning and is vertical for a boat gyro. The input axis is the axis about which input torques are applied. For a boat, the principal input axis is the longitudinal axis of the boat since that is the axis around which the boat rolls. The principal output axis is the transverse (athwartship) axis about which the gyro rotates or precesses in reaction to an input.

When the boat rolls, the rotation acts as an input to the gyro, causing the gyro to generate rotation around its output axis such that the spin axis rotates to align itself with the input axis. This output rotation is called precession and, in the boat case, the gyro will rotate fore and aft about the output or gimbal axis.

Angular momentum is the measure of effectiveness for a gyro stabilizer, analogous to horsepower ratings on a diesel engine or kilowatts on a generator. In specifications for gyro stabilizers, the total angular momentum (moment of inertia multiplied by spin speed) is the key quantity. In modern designs, the output axis torque can be used to control the angle of the stabilizer fins (see above) to counteract the roll of the boat so that only a small gyroscope is needed. The idea for gyro controlling a ship's fin stabilizers was first proposed in 1932 by a General Electric scientist, Dr Alexanderson. He proposed a gyro to control the current to the electric motors on the stabilizer fins, with the actuating instructions being generated by thyratron vacuum tubes.[3]

Calculated stability conditions

When a hull is designed, stability calculations are performed for the intact and damaged states of the vessel. Ships are usually designed to slightly exceed the stability requirements (below), as they are usually tested for this by a classification society.

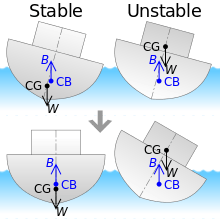

Intact stability

Intact stability calculations are relatively straightforward and involve taking all the centers of mass of objects on the vessel which are then computed/calculated to identify the center of gravity of the vessel, and the center of buoyancy of the hull. Cargo arrangements and loadings, crane operations, and the design sea states are usually taken into account. The photo at right illustrates a common misconception about vessels. In fact, in the vast majority of vessels, the center of gravity is well above the center of buoyancy. The ship is stable because as it begins to heel, one side of the hull begins to rise from the water and the other side begins to submerge. This causes the center of buoyancy to shift toward the side that is lower in the water. The job of the naval architect is to make sure that the center of buoyancy shifts outboard of the center of gravity as the ship heels. A line drawn from the center of buoyancy in a slightly heeled condition vertically will intersect the centerline at a point called the metacenter. As long as the metacenter is further above the keel than the center of gravity, the ship is stable in an upright condition.

Damage stability (Stability in the damaged condition)

Damage stability calculations are much more complicated than intact stability. Software utilizing numerical methods are typically employed because the areas and volumes can quickly become tedious and long to compute using other methods.

The loss of stability from flooding may be due in part to the free surface effect. Water accumulating in the hull usually drains to the bilges, lowering the centre of gravity and actually decreasing (It should read as increasing, since water will add as a bottom weight there by increasing GM) the metacentric height. This assumes the ship remains stationary and upright. However, once the ship is inclined to any degree (a wave strikes it for example), the fluid in the bilge moves to the low side. This results in a list.

Stability is also lost in flooding when, for example, an empty tank is filled with seawater. The lost buoyancy of the tank results in that section of the ship lowering into the water slightly. This creates a list unless the tank is on the centerline of the vessel.

In stability calculations, when a tank is filled, its contents are assumed to be lost and replaced by seawater. If these contents are lighter than seawater, (light oil for example) then buoyancy is lost and the section lowers slightly in the water accordingly.

For merchant vessels, and increasingly for passenger vessels, the damage stability calculations are of a probabilistic nature. That is, instead of assessing the ship for one compartment failure, a situation where two or even up to three compartments are flooded will be assessed as well. This is a concept in which the chance that a compartment is damaged is combined with the consequences for the ship, resulting in a damage stability index number that has to comply with certain regulations.

Required stability

In order to be acceptable to classification societies such as the Bureau Veritas, American Bureau of Shipping, Lloyd's Register of Ships and Det Norske Veritas, the blueprints of the ship must be provided for independent review by the classification society. Calculations must also be provided which follow a structure outlined in the regulations for the country in which the ship intends to be flagged.

Within this framework different countries establish requirements that must be met. For U.S.-flagged vessels, blueprints and stability calculations are checked against the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations and International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea conventions. Ships are required to be stable in the conditions to which they are designed for, in both undamaged and damaged states. The extent of damage required to design for is included in the regulations. The assumed hole is calculated as fractions of the length and breadth of the vessel, and is to be placed in the area of the ship where it would cause the most damage to vessel stability.

In addition, United States Coast Guard rules apply to vessels operating in U.S. ports and in U.S. waters. Generally these Coast Guard rules concern a minimum metacentric height or a minimum righting moment. Because different countries may have different requirements for the minimum metacentric height, most ships are now fitted with stability computers that calculate this distance on the fly based on the cargo or crew loading. There are many commercially available computer programs used for this task.

See also

- Free surface effect

- Stabilization at zero speed

- Mary Rose

- Kronan (ship)

- SS Eastland

- Niobe (schooner)

- Pamir (ship)

- Inclining test

References

- Title 46 U.S. Code of Federal Regulations

- ABS Rules for Building and Classing Steel Vessels 2007

- Overview of a few common Roll Attenuation Strategies

- ↑ From Warrior to Dreadnought by D.K. Brown, Chatham Publishing (June 1997)

- ↑ "Italian Liner To Defy The Waves" Popular Mechanics, April 1931

- ↑ "Fins Purposed For Big Liners To Prevent Rolling" Popular Mechanics, August 1932