Iron(III) chloride

_chloride_hexahydrate.jpg) | |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Iron(III) chloride Iron trichloride | |||

| Other names

Ferric chloride Molysite Flores martis | |||

| Identifiers | |||

| 7705-08-0 10025-77-1 (hexahydrate) | |||

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image | ||

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30808 | ||

| ChemSpider | 22792 | ||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.846 | ||

| EC Number | 231-729-4 | ||

| PubChem | 24380 | ||

| RTECS number | LJ9100000 | ||

| UNII | U38V3ZVV3V 0I2XIN602U (hexahydrate) | ||

| UN number | 1773 (anhydrous) 2582 (aq. soln.) | ||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| FeCl3 | |||

| Molar mass | 162.2 g/mol (anhydrous) 270.3 g/mol (hexahydrate) | ||

| Appearance | green-black by reflected light; purple-red by transmitted light hexahydrate: yellow solid aq. solutions: brown | ||

| Odor | slight HCl | ||

| Density | 2.898 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 1.82 g/cm3 (hexahydrate) | ||

| Melting point | 306 °C (583 °F; 579 K) (anhydrous) 37 °C (99 °F; 310 K) (hexahydrate) | ||

| Boiling point | 315 °C (599 °F; 588 K) (anhydrous, decomposes) 280 °C (536 °F; 553 K) (hexahydrate, decomposes) partial decomposition to FeCl2 + Cl2 | ||

| 74.4 g/100 mL (0 °C)[1] 92 g/100 mL (hexahydrate, 20 °C) | |||

| Solubility in acetone Methanol Ethanol Diethyl ether |

63 g/100 ml (18 °C) highly soluble 83 g/100 ml highly soluble | ||

| Viscosity | 40% solution: 12 cP | ||

| Structure | |||

| hexagonal | |||

| octahedral | |||

| Hazards[2][3][Note 1] | |||

| Safety data sheet | ICSC | ||

| GHS pictograms |   | ||

| GHS signal word | DANGER | ||

| H290, H302, H314, H318 | |||

| P234, P260, P264, P270, P273, P280, P301+312, P301+330+331, P303+361+353, P363, P304+340, P310, P321, P305+351+338 | |||

| NFPA 704 | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |||

| REL (Recommended) |

TWA 1 mg/m3[5] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

| Other anions |

Iron(III) fluoride Iron(III) bromide | ||

| Other cations |

Iron(II) chloride Manganese(II) chloride Cobalt(II) chloride Ruthenium(III) chloride | ||

| Related coagulants |

Iron(II) sulfate Polyaluminium chloride | ||

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Iron(III) chloride, also called ferric chloride, is an industrial scale commodity chemical compound, with the formula FeCl3 and with iron in the +3 oxidation state. The colour of iron(III) chloride crystals depends on the viewing angle: by reflected light the crystals appear dark green, but by transmitted light they appear purple-red. Anhydrous iron(III) chloride is deliquescent, forming hydrated hydrogen chloride mists in moist air. It is rarely observed in its natural form, the mineral molysite, known mainly from some fumaroles.

When dissolved in water, iron(III) chloride undergoes hydrolysis and gives off heat in an exothermic reaction. The resulting brown, acidic, and corrosive solution is used as a flocculant in sewage treatment and drinking water production, and as an etchant for copper-based metals in printed circuit boards. Anhydrous iron(III) chloride is a fairly strong Lewis acid, and it is used as a catalyst in organic synthesis.

Nomenclature

The descriptor hydrated or anhydrous is used when referring to iron(III) chloride, to distinguish between the two common forms. The hexahydrate is usually given as the simplified empirical formula FeCl3⋅6H2O. It may also be given as trans-[Fe(H2O)4Cl2]Cl⋅2H2O and the systematic name tetraaquadichloroiron(III) chloride dihydrate, which more clearly represents its structure.

Structure and properties

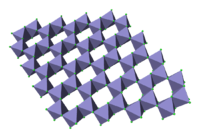

Anhydrous iron(III) chloride adopts the BiI3 structure, which features octahedral Fe(III) centres interconnected by two-coordinate chloride ligands. Iron(III) chloride hexahydrate consists of trans-[Fe(H2O)4Cl2]+ cationic complexes and chloride anions, with the remaining two H2O molecules embedded within the monoclinic crystal structure.[6]

Iron(III) chloride has a relatively low melting point and boils at around 315 °C. The vapour consists of the dimer Fe2Cl6 (c.f. aluminium chloride) which increasingly dissociates into the monomeric FeCl3 (D3h point group molecular symmetry) at higher temperature, in competition with its reversible decomposition to give iron(II) chloride and chlorine gas.[7]

Preparation

Anhydrous iron(III) chloride may be prepared by union of the elements:[8]

Solutions of iron(III) chloride are produced industrially both from iron and from ore, in a closed-loop process.

- Dissolving iron ore in hydrochloric acid

- Fe3O4(s) + 8 HCl(aq) → FeCl2(aq) + 2 FeCl3(aq) + 4 H2O

- Oxidation of iron (II) chloride with chlorine

- 2 FeCl2(aq) + Cl2(g) → 2 FeCl3(aq)

- Oxidation of iron (II) chloride with oxygen

- 4FeCl2(aq) + O2 + 4HCl → 4FeCl3(aq) + 2H2O

- Reacting Iron with hydrochloric acid, then with hydrogen peroxide. The hydrogen peroxide is the oxidant in turning ferrous chloride into ferric chloride

Like many other hydrated metal chlorides, hydrated iron(III) chloride can be converted to the anhydrous salt by refluxing with thionyl chloride.[9] Conversion of the hydrate to anhydrous iron(III) chloride is not accomplished by heating, as HCl and iron oxychlorides are produced.

Reactions

Iron(III) chloride undergoes hydrolysis to give an acidic solution. When heated with iron(III) oxide at 350 °C, iron(III) chloride gives iron oxychloride, a layered solid and intercalation host.[10]

- FeCl3 + Fe2O3 → 3 FeOCl

It is a moderately strong Lewis acid, forming adducts with Lewis bases such as triphenylphosphine oxide, e.g. FeCl3(OPPh3)2 where Ph = phenyl. It also reacts with other chloride salts to give the yellow tetrahedral FeCl4− ion. Salts of FeCl4− in hydrochloric acid can be extracted into diethyl ether.

Alkali metal alkoxides react to give the metal alkoxide complexes of varying complexity.[11] The compounds can be dimeric or trimeric.[12] In the solid phase a variety of multinuclear complexes have been described for the nominal stoichiometric reaction between FeCl3 and sodium ethoxide:[13][14]

- FeCl3 + 3 [C2H5O]−Na+ → Fe(OC2H5)3 + 3 NaCl

Oxalates react rapidly with aqueous iron(III) chloride to give [Fe(C2O4)3]3−. Other carboxylate salts form complexes, e.g. citrate and tartrate.

Oxidation

Iron(III) chloride is a mild oxidising agent, for example, it is capable of oxidising copper(I) chloride to copper(II) chloride.

- FeCl3 + CuCl → FeCl2 + CuCl2

It also reacts with iron to form iron(II) chloride:

- 2 FeCl3 + Fe → 3 FeCl2

Reducing agents such as hydrazine convert iron(III) chloride to complexes of iron(II).

Uses

Industrial

In industrial application, iron(III) chloride is used in sewage treatment and drinking water production.[15] In this application, FeCl3 in slightly basic water reacts with the hydroxide ion to form a floc of iron(III) hydroxide, or more precisely formulated as FeO(OH)−, that can remove suspended materials.

- [Fe(H2O)6]3+ + 4 HO− → [Fe(H2O)2(HO)4]− + 4 H2O → [Fe(H2O)O(HO)2]− + 6 H2O

It is also used as a leaching agent in chloride hydrometallurgy,[16] for example in the production of Si from FeSi. (Silgrain process)[17]

Another important application of iron(III) chloride is etching copper in two-step redox reaction to copper(I) chloride and then to copper(II) chloride in the production of printed circuit boards.[18]

- FeCl3 + Cu → FeCl2 + CuCl

- FeCl3 + CuCl → FeCl2 + CuCl2

Iron(III) chloride is used as catalyst for the reaction of ethylene with chlorine, forming ethylene dichloride (1,2-dichloroethane), an important commodity chemical, which is mainly used for the industrial production of vinyl chloride, the monomer for making PVC.

- H2C=CH2 + Cl2 → ClCH2CH2Cl

Laboratory use

In the laboratory iron(III) chloride is commonly employed as a Lewis acid for catalysing reactions such as chlorination of aromatic compounds and Friedel-Crafts reaction of aromatics. It is less powerful than aluminium chloride, but in some cases this mildness leads to higher yields, for example in the alkylation of benzene:

The ferric chloride test is a traditional colorimetric test for phenols, which uses a 1% iron(III) chloride solution that has been neutralised with sodium hydroxide until a slight precipitate of FeO(OH) is formed.[19] The mixture is filtered before use. The organic substance is dissolved in water, methanol or ethanol, then the neutralised iron(III) chloride solution is added—a transient or permanent coloration (usually purple, green or blue) indicates the presence of a phenol or enol.

This reaction is exploited in the Trinder spot test, which is used to indicate the presence of salicylates, particularly salicylic acid, which contains a phenolic OH group.

This test can be used to detect the presence of gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid and gamma-butyrolactone,[20] which cause it to turn red-brown.

Other uses

- Used in anhydrous form as a drying reagent in certain reactions.

- Used to detect the presence of phenol compounds in organic synthesis e.g.: examining purity of synthesised Aspirin.

- Used in water and wastewater treatment to precipitate phosphate as iron(III) phosphate.

- Used by American coin collectors to identify the dates of Buffalo nickels that are so badly worn that the date is no longer visible.

- Used by bladesmiths and artisans in pattern welding to etch the metal, giving it a contrasting effect, to view metal layering or imperfections.

- Used to etch the widmanstatten pattern in iron meteorites.

- Necessary for the etching of photogravure plates for printing photographic and fine art images in intaglio and for etching rotogravure cylinders used in the printing industry.

- Used to make printed circuit boards (PCBs).

- Used in veterinary practice to treat overcropping of an animal's claws, particularly when the overcropping results in bleeding.

- Reacts with cyclopentadienylmagnesium bromide in one preparation of ferrocene, a metal-sandwich complex.[21]

- Sometimes used in a technique of Raku ware firing, the iron coloring a pottery piece shades of pink, brown, and orange.

- Used to test the pitting and crevice corrosion resistance of stainless steels and other alloys.

- Used in conjunction with NaI in acetonitrile to mildly reduce organic azides to primary amines.[22]

- Used in an animal thrombosis model.[23]

- Used in energy storage systems

- Historically it was used to make direct positive blueprints; U.S. patent 241,713, May 17, 1881[24]

- A component of modified Carnoy's solution used for surgical treatment of keratocystic odontogenic tumor (KOT)

Safety

Iron(III) chloride is toxic, highly corrosive and acidic. The anhydrous material is a powerful dehydrating agent.

Although reports of poisoning in humans are rare, ingestion of ferric chloride can result in serious morbidity and mortality. Inappropriate labeling and storage lead to accidental swallowing or misdiagnosis. Early diagnosis is important, especially in seriously poisoned patients.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

References

- ↑ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- ↑ HSNO Chemical Classification Information Database, New Zealand Environmental Risk Management Authority, retrieved 2010-09-19

- ↑ Various suppliers, collated by the Baylor College of Dentistry, Texas A&M University. (accessed 2010-09-19)

- ↑ GHS classification – ID 831, Japanese GHS Inter-ministerial Committee, 2006, retrieved 2010-09-19

- ↑ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards #0346". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ↑ Lind, M. D. (1967). "Crystal Structure of Ferric Chloride Hexahydrate". J. Chem. Phys. 47: 990. doi:10.1063/1.1712067.

- ↑ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑ Tarr, B. R.; Booth, Harold S.; Dolance, Albert (1950). "Anhydrous Iron(III) Chloride". Inorganic Syntheses. Inorganic Syntheses. 3: 191–194. doi:10.1002/9780470132340.ch51. ISBN 978-0-470-13234-0.

- ↑ Pray, Alfred R.; Richard F. Heitmiller; Stanley Strycker (1990). "Anhydrous Metal Chlorides". Inorganic Syntheses. 28: 321–323. doi:10.1002/9780470132593.ch80. ISBN 978-0-470-13259-3.

- ↑ Kikkawa, S.; Kanamaru, F.; Koizumi, M.; Rich, Suzanne M.; Jacobson, Allan (1984-01-01). Jr, Smith L. Holt, ed. Layered Intercalation Compounds. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 86–89. doi:10.1002/9780470132531.ch17. ISBN 9780470132531.

- ↑ The chemistry of metal alkoxides, Nataliya Ya Turova, 12.22.1 'Synthesis', p. 481 google books link

- ↑ Alkoxo and aryloxo derivatives of metals By D. C. Bradley, 3.2.10, Alkoxides of later 3d metals, p. 69 google books links

- ↑ Fe9O3(OC2H5)21·C2H5OH—A New Structure Type of an Uncharged Iron(III) Oxide-Alkoxide Cluster, Michael Veith, Frank Grätz, Volker Huch, European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry, Vol 2001, Issue 2, pp. 367–368 online link

- ↑ The synthesis of iron (III) ethoxide revisited: Characterization of the metathesis products of iron (III) halides and sodium ethoxide, Gulaim A. Seisenbaevaa, Suresh Gohila, Evgeniya V. Suslovab, Tatiana V. Rogovab, Nataliya Ya. Turovab, Vadim G. Kesslera, Inorganica Chimica Acta, Volume 358, Issue 12, 1/8/2005, pp. 3506–3512, online link

- ↑ Water Treatment Chemicals (PDF). Akzo Nobel Base Chemicals. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Separation and Purification Technology 51 (2006) pp. 332–337

- ↑ Chem. Eng. Sci. 61 (2006) pp. 229–245

- ↑ Greenwood, N. N.; A. Earnshaw (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- ↑ Furnell, B. S.; et al. (1989). Vogel's Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: Longman/Wiley.

- ↑ Zhang, S. Y.; Huang, Z. P. (2006). "A color test for rapid screening of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and gamma-butyrolactone (GBL) in drink and urine". Fa yi xue za zhi. 22 (6): 424–7. PMID 17285863.

- ↑ Kealy, T. J.; Pauson, P. L. (1951). "A New Type of Organo-Iron Compound". Nature. 168 (4285): 1040. doi:10.1038/1681039b0.

- ↑ Kamal, Ahmed; Ramana, K.; Ankati, H.; Ramana, A (2002). "Mild and efficient reduction of azides to amines: synthesis of fused [2,1-b]quinazolines". Tetrahedron Letters. 43 (38): 6961. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(02)01454-5.

- ↑ Tseng, Michael; Dozier, A.; Haribabu, B.; Graham, U. M. (2006). "Transendothelial migration of ferric ion in FeCl3 injured murine common carotid artery". Thrombosis Research. 118 (2): 275–280. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2005.09.004. PMID 16243382.

- ↑ Lietze, Ernst (1888). Modern Heliographic Processes. New York: D. Van Norstrand Company. p. 65.

Further reading

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- D. Nicholls, Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements, Macmillan Press, London, 1973.

- A.F. Wells, 'Structural Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1984.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.

- Handbook of Reagents for Organic Synthesis: Acidic and Basic Reagents, (H. J. Reich, J. H. Rigby, eds.), Wiley, New York, 1999.