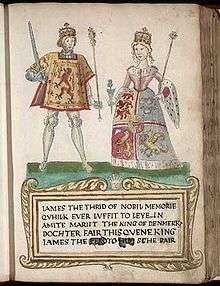

James III of Scotland

| James III | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of Scots | |

| Reign | 3 August 1460 – 11 June 1488 |

| Coronation | 10 August 1460[1] |

| Predecessor | James II |

| Successor | James IV |

| Regents |

See

|

| Born |

10 July 1451 Stirling or St Andrews Castles |

| Died |

11 June 1488 (aged 36) Sauchie Burn, Scotland |

| Burial | Cambuskenneth Abbey, Stirling |

| Spouse | Margaret of Denmark |

| Issue |

James IV of Scotland James, Duke of Ross John, Earl of Mar |

| House | Stewart |

| Father | James II of Scotland |

| Mother | Mary of Guelders |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

James III (10 July 1451 – 11 June 1488) was King of Scots from 1460 to 1488. James was an unpopular and ineffective monarch owing to an unwillingness to administer justice fairly, a policy of pursuing alliance with the Kingdom of England, and a disastrous relationship with nearly all his extended family. However, it was through his marriage to Margaret of Denmark that the Orkney and Shetland islands became Scottish.

His reputation as the first Renaissance monarch in Scotland has sometimes been exaggerated, based on attacks on him in later chronicles for being more interested in such unmanly pursuits as music than hunting, riding and leading his kingdom into war. In fact, the artistic legacy of his reign is slight, especially when compared to that of his successors, James IV and James V. Such evidence as there is consists of portrait coins produced during his reign that display the king in three-quarter profile wearing an imperial crown, the Trinity Altarpiece by Hugo van der Goes, which was probably not commissioned by the king, and an unusual hexagonal chapel at Restalrig near Edinburgh, perhaps inspired by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Early life

James was born to James II of Scotland and Mary of Guelders. His exact date and place of birth have been a matter of debate. Claims were made that he was born in May 1452, or 10 or 20 July 1451. The place of birth was either Stirling Castle or the Castle of St Andrews, depending on the year. His most recent biographer, the historian Norman Macdougall, argued strongly for late May 1452 at St Andrews, Fife. He succeeded his father James II on 3 August 1460 and was crowned at Kelso Abbey, Roxburghshire, a week later.

During his childhood, the government was led by three successive factions, first the King's mother, Mary of Guelders (1460–1463) (who briefly secured the return of the burgh of Berwick to Scotland), then James Kennedy, Bishop of St Andrews, and Gilbert, Lord Kennedy (1463–1466), then Robert, Lord Boyd (1466–1469).

Relation to the Boyd faction

The Boyd faction made itself unpopular, especially with the king, through self-aggrandisement. Lord Boyd's son Thomas was made Earl of Arran and married to the king's sister Mary. However, the family successfully negotiated the king's marriage to Margaret of Denmark, daughter of Christian I of Denmark in 1469 as a part of ending the annual fee owed to Norway for the Western Isles (agreed in the Treaty of Perth in 1266), and receiving Orkney and Shetland (theoretically only as a temporary measure to cover Margaret's dowry). When James permanently annexed the islands to the crown in 1472, Scotland reached its greatest ever territorial extent.[2]

Marriage

James married Margaret of Denmark in July 1469 at Holyrood Abbey, Edinburgh. Christian I of Denmark gave the Orkney and Shetland Islands to Scotland in lieu of a dowry. The marriage produced three sons:

Break with the Boyds

Conflict broke out between James and the Boyd family following the marriage to Princess Mary. Robert and Thomas Boyd (with Princess Mary) were out of the country involved in diplomacy when their regime was overthrown. Mary's marriage was later declared void in 1473. The family of Sir Alexander Boyd was executed by James in 1469.

James and the Lords of the Isles

James became powerful enough to attempt to manage the Lord of the Isles who ruled over the Western Isles and Highlands of Scotland in 1475. The treaty made by the Lords with England at Ardtornish in 1462 was used as evidence of their usurpation of royal power. John of Islay, Earl of Ross, Lord of the Isles was censured for making his son Angus his lieutenant and for besieging Rothesay Castle in the Isle of Bute. John, Lord of the Isles was ordered to appear for trial in Edinburgh on 1 December and when he did not attend, he was declared forfeit. The Earls of Lennox, Argyll, Atholl and Huntly were ordered to put the forfeiture in practice. John, Lord of the Isles, came to Edinburgh in July 1476 and the forfeiture was rescinded, but he resigned to the crown the Earldom of Ross, lands in Kintyre and Knapdale, and the offices of Sheriff of Inverness and Nairn. James then made John a Lord of Parliament as Lord of the Isles. In April 1478 Parliament required John to answer for his assistance to rebels who held Castle Sween against the crown. In December John received confirmation of his 1476 charters.[3]

First alliance and then war with England

James's policies during the 1470s revolved primarily around ambitious continental schemes for territorial expansion and alliance with England. Between 1471 and 1473 he suggested annexations or invasions of Brittany, Saintonge and Guelders. These unrealistic aims resulted in parliamentary criticism, especially since the king was reluctant to deal with the more humdrum business of administering justice at home.

In 1474 a marriage alliance was agreed to with Edward IV of England by which the future James IV of Scotland was to marry Princess Cecily of York, daughter of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville. It might have been a sensible move for Scotland, but it went against the traditional enmity of the two countries dating back to the reign of Robert I and the Wars of Independence, not to mention the vested interests of the border nobility. The alliance, therefore (and the taxes raised to pay for the marriage) was at least one of the reasons why the king was unpopular by 1479.

Also during the 1470s conflict developed between the king and his two brothers, Alexander, Duke of Albany, and John, Earl of Mar. Mar died suspiciously in Edinburgh in 1480 and his estates were forfeited, possibly given to a royal favourite, Robert Cochrane. Albany fled to France in 1479, accused of treason and breaking the alliance with England.

But by 1479 the alliance was collapsing and war with England existed on an intermittent level in 1480–1482. In 1482 Edward IV launched a full-scale invasion led by the Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III, including the Duke of Albany, styled "Alexander IV", as part of the invasion party. James, in attempting to lead his subjects against the invasion, was arrested by a group of disaffected nobles at Lauder Bridge in July 1482. It has been suggested that the nobles were already in league with Albany. The king was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle and a new regime, led by "lieutenant-general" Albany, became established during the autumn of 1482. Meanwhile, the English army, unable to take Edinburgh Castle, ran out of money and returned to England, having taken Berwick-upon-Tweed for the last time.

Restoration to power

James was able to regain power by buying off members of Albany's government, such that by December 1482 Albany's government was collapsing. In particular his attempt to claim the vacant earldom of Mar led to the intervention of the powerful George Gordon, 2nd Earl of Huntly, on the king's side.

In January 1483 Albany fled to his estates at Dunbar. The death of his patron, Edward IV, on 9 April, left Albany in a weak position, and he fled over the border to England. He remained there until 1484, when he launched another abortive invasion at Lochmaben. Another attempted return has been argued to have occurred in 1485, when (admittedly suspect) accounts suggest he escaped from Edinburgh Castle on a rope made of sheets. Certainly his right-hand man, James Liddale of Halkerston, was arrested and executed around that time. Albany was killed in a joust in Paris later that year.

On 5 March 1486 Pope Innocent VIII blessed a Golden Rose and sent it James III. It was an annual custom to send the rose to a deserving prince. Giacomo Passarelli, Bishop of Imola, brought the rose to Scotland, and returned to London to complete the dispensation for the marriage of Henry VII of England.[4]

Death in battle

Despite a lucky escape in 1482, when he easily could have been murdered or executed in an attempt to bring his son to the throne, James did not reform his behaviour during the 1480s. Obsessive attempts to secure alliance with England continued, although they made little sense given the prevailing politics. He continued to favour a group of "familiars" unpopular with the more powerful magnates. He refused to travel for the implementation of justice and remained invariably resident in Edinburgh. He was also estranged from his wife, Margaret of Denmark, who lived in Stirling, and increasingly his eldest son. He favoured his second son instead.

In January 1488, in Parliament, James tried to gain supporters by making his second son Duke of Ross and four Lairds full Lords of Parliament. These allies were John Drummond of Cargill, made Lord Drummond; Robert Crichton of Sanquhar, made Lord Sanquhar; John Hay of Yester, made Lord Hay of Yester; and the Knight William Ruthven, made Lord Ruthven. But opposition to James was led by the Earls of Angus and Argyll, and the Home and Hepburn families. James's eldest son and heir, the future James IV, was delivered into the hands of the rebels by Schaw of Sauchie on 2 February 1488. The Prince became the figurehead of the opposition party, perhaps reluctantly, or perhaps provoked by the favouritism given to his younger brother. Matters came to a head on 11 June 1488, when the king faced the army raised by the disaffected nobles and many former councillors near Stirling, at the Battle of Sauchieburn, and was defeated and killed.[5]

It is unknown whether James III was killed in the battle or while fleeing. He is buried at Cambuskenneth Abbey.[6] Accounts of 16th-century chroniclers such as Adam Abell, Robert Lindsay of Pitscottie, John Leslie and George Buchanan alleged that the king was assassinated near Bannockburn, soon after the battle, at Milltown,[7]

Fictional portrayals

James III has been depicted in plays, historical novels and short stories. They include:

- Price of a Princess (1994) by Nigel Tranter. The book takes place in the years 1465–1469. The main character is Mary Stewart, Countess of Arran, a sister of James III. She is depicted joining her husband Thomas Boyd, Earl of Arran in a mission to the court of Christian I of Denmark. The two negotiate the ceding of Orkney and Shetland from the Kalmar Union to the Kingdom of Scotland.[8]

- Lord in Waiting (1994) by Nigel Tranter. The book takes place in the years 1474–1488. It covers events of the reign of James III, seen from the perspective of "John, Lord of Douglas".[9] James III is depicted influenced by one William Sheves, the court astrologer and alchemist. Douglas would rather have Mary Stewart (see above) on the throne.[10]

- The Admiral (2001) by Nigel Tranter. The book takes place in the years 1480–1530. It covers the career of Andrew Wood of Largo and the formation of the Royal Scots Navy. James III is depicted favoring Wood with the title of Lord High Admiral of Scotland.[8]

- James III: The True Mirror (2014) by Rona Munro. A co-production between the National Theatre of Scotland, Edinburgh International Festival and the National Theatre of Great Britain. The James Plays – James I, James II and James III – are a trio of history plays by Rona Munro. Each play stands alone as a vision of a country tussling with its past and future. This play concentrates on James' relationships with his wife Margaret, his court favourites and the powerful lords he has alienated.[11]

- The Unicorn Hunt (1993) by Dorothy Dunnett. Volume 5 in The House of Niccolò series.

- To Lie with Lions (1995) by Dorothy Dunnett. Volume 6 in The House of Niccolò series.

- Gemini (2000) by Dorothy Dunnett. Volume 8 in The House of Niccolò series.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of James III of Scotland | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ The Peerage — James III. Thepeerage.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (1991). Scotland A New History. 155-56: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-9893-0.

- ↑ J. & R. Munro ed., Acts of the Lords of the Isles, (SHS, Edinburgh 1986), pp. lxx-lxxii

- ↑ Calendar State Papers Milan, vol.1 (1912), 247: Burns, Charles, 'Papal Gifts' in Innes Review, 20 (1969), pp.150–194: Chrimes, Stanley, Henry VII, Yale (1999), 66, 330–1

- ↑ Mackie, R.L., James IV, (1958), 36–44.

- ↑ Macdougall, Norman. "James III". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14589. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Recent archaeological survey of Milton, alleged site of assassination. Scotlandsplaces.gov.uk. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- 1 2 "Nigel Tranter Historical Novels", listed by chronological order. Cunninghamh.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ↑ "Nigel Tranter Historical Novels", listed by chronological order of events. Cunninghamh.tripod.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ↑ "Tranter First edition books, Publication timeline", Part IV covers books published from 1991 to 2005. Cunninghamh.tripod.com (2003-03-03). Retrieved on 2011-10-02.

- ↑ "Edinburgh International Festival 2014"

- Macdougall, Norman, James III, A Political Study, John Donald (1982)

External links

| James III of Scotland Born: 1451/2 Died: 11 June 1488 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James II |

King of Scots 3 August 1460 – 11 June 1488 |

Succeeded by James IV |