James Young (chemist)

| James Young | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

13 July 1811 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died |

13 May 1883 (aged 71) Wemyss Bay, Scotland |

| Nationality | Scottish |

James Young (13 July 1811 – 13 May 1883) was a Scottish chemist best known for his method of distilling paraffin from coal and oil shales.

Early life

James Young was born in the Drygate area of Glasgow, the son of John Young, a cabinetmaker and joiner. He became his father's apprentice at an early age, and educated himself at night school, attending evening classes at the nearby Anderson's College (now Strathclyde University) from the age of 19. He met Thomas Graham at Anderson's College, who had just been appointed as a lecturer on chemistry and in 1831 was appointed as his assistant and occasionally took some of his lectures. While at Anderson's College he also met and befriended the famous explorer David Livingstone; this relationship was to continue until Livingstone's death in Africa many years later.

In Young's first scientific paper, dated 4 January 1837, he described a modification of a voltaic battery invented by Michael Faraday. Later that same year he moved with Graham to University College, London where he helped him with experimental work.

Career

Chemicals

In 1839 Young was appointed manager at James Muspratt's chemical works Newton-le-Willows, near St Helens, Merseyside, and in 1844 to Tennants, Clow & Co. at Manchester, for whom he devised a method of making sodium stannate directly from cassiterite.

Potato blight

In 1845 he served on a committee of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society for the investigation of potato blight, and suggested immersing the potatoes in dilute sulphuric acid as a means of combatting the disease; he was not elected a member of the Society until 19 October 1847. Finding the Manchester Guardian newspaper insufficiently liberal, he also began a movement for the establishment of the Manchester Examiner newspaper which was first published in 1846.

Oils

In 1847 Young had his attention called to a natural petroleum seepage in the Riddings colliery at Alfreton, Derbyshire from which he distilled a light thin oil suitable for use as lamp oil, at the same time obtaining a thicker oil suitable for lubricating machinery.

In 1848 Young left Tennants', and in partnership with his friend and assistant Edward Meldrum, set up a small business refining the crude oil. The new oils were successful, but the supply of oil from the coal mine soon began to fail (eventually being exhausted in 1851). Young, noticing that the oil was dripping from the sandstone roof of the coal mine, theorised that it somehow originated from the action of heat on the coal seam and from this thought that it might be produced artificially.

Following up this idea, he tried many experiments and eventually succeeded in producing, by distilling cannel coal at a low heat, a fluid resembling petroleum, which when treated in the same way as the seep oil gave similar products. Young found that by slow distillation he could obtain a number of useful liquids from it, one of which he named "paraffine oil" because at low temperatures it congealed into a substance resembling paraffin wax.[1]

Patents

The production of these oils and solid paraffin wax from coal formed the subject of his patent dated 17 October 1850. In 1850 Young & Meldrum and Edward William Binney entered into partnership under the title of E.W. Binney & Co. at Bathgate in West Lothian and E. Meldrum & Co. at Glasgow; their works at Bathgate were completed in 1851 and became the first truly commercial oil-works in the world, using oil extracted from locally mined torbanite, lamosite, and bituminous coal to manufacture naphtha and lubricating oils; paraffin for fuel use and solid paraffin were not sold till 1856.

In 1852 Young left Manchester to live in Scotland and that same year took out a US patent for the production of paraffin oil by distillation of coal. Both the US and UK patents were subsequently upheld in both countries in a series of lawsuits and other producers were obliged to pay him royalties.[1]

Young's Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company

In 1865 Young bought out his business partners and built second and larger works at Addiewell, near West Calder, and in 1866 sold the concern to Young's Paraffin Light and Mineral Oil Company. Although Young remained in the company, he took no active part in it, instead withdrawing from business to occupy himself with looking after the estates which he had purchased, yachting, travelling, and scientific pursuits. The company continued to grow and expanded its operations, selling paraffin oil and paraffin lamps all over the world and earning for its founder the affectionate nickname 'Paraffin' Young. Other companies worked under license from Young's firm, and paraffin manufacture spread over the south of Scotland.

When the reserves of torbanite eventually gave out the company moved on to pioneer the exploitation of West Lothian's oil shale (lamosite) deposits, if not so rich in oil as cannel coal and torbanite. In 1862 the distillation plants began production and by the 1900s nearly 2 million tons of shale were being extracted annually, employing 4,000 men.

Other work

- Young made significant discoveries in rustproofing ships in 1872, which were later adopted by the Royal Navy. Noticing that bilge water was acidic, he suggested that quicklime could be used to prevent it corroding iron ships.[2]

- Young worked with Professor George Forbes on the speed of light around 1880, using an improved version of Hippolyte Fizeau's method.[3]

Honours

- In 1847 Young was elected to the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

- In 1861 he was elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.

- From 1868–1877 he was President of Anderson's College and founded the Young Chair of Technical Chemistry at the College.

- In 1873 Young was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society

- In 1879 he was awarded an Honorary LI.D of St. Andrews University.

- From 1879–1881 he was Vice-President of the Chemical Society.

Retirement and death

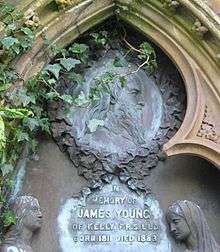

Young retired from the operation of the company in 1870, and died at age 71 in his home Kelly, near Wemyss Bay, on 13 May 1883, being survived by his wife, Mary Young, and his three sons and four daughters. He was buried at Inverkip.

Legacy

- Statues of his old professor, Thomas Graham, and of his fellow student and lifelong friend, David Livingstone, which stand respectively in George Square, Glasgow, and at Glasgow Cathedral, were erected by him.

- From 1855 James 'Paraffin' Young lived at Limefield House, Polbeth. A sycamore tree which Livingstone planted in 1864 is still flourishing in the grounds of Limefield House. There too one can see a miniature version of the "Victoria Falls", which the missionary discovered in the mid-19th century. It was built, as a tribute to Livingstone, by Young on the little stream which runs through the estate.

- Young had a lifelong friendship with David Livingstone, whom he had met at Anderson's College. He gave generously towards the expenses of Livingstone's African expeditions, and contributed to a search expedition, which proved too late to find Livingstone alive. He also had Livingstone's servants brought to England, and presented to Glasgow a statue to his memory, which was erected in George Square, Glasgow.

- The James Young High School in Livingston, the Bathgate branch of the pub chain Wetherspoons and the James Young Halls at the University of Strathclyde are all named after him.

- In 2011 he was one of seven inaugural inductees to the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame.[4]

See also

- Pumpherston

- Luther Atwood

- Abraham Pineo Gesner

- Alexander Selligue

- History of the oil shale industry

- Monkland Railways

- Wilsontown, Morningside and Coltness Railway

Notes

- 1 2 Russell, Loris S. (2003). A Heritage of Light: Lamps and Lighting in the Early Canadian Home. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3765-8.

- ↑ Young, James (November 1869 – January 1872). "On the Preservation of Iron Ships". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Royal Society of Edinburgh. 7: 702.

- ↑ Pippard, Sir Brian (2001). "Dispersion in the Ether: Light over the Water". Physics in Perspective. Basel: Springer. 3 (3): 258–270. doi:10.1007/pl00000533.

- ↑ "Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame". engineeringhalloffame.org. 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

External links

-

Media related to James Young (chemist) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to James Young (chemist) at Wikimedia Commons  "Young, James (1811-1883)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Young, James (1811-1883)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.