Japanese battleship Fuji

Fuji at anchor in 1908 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Fuji |

| Namesake: | Mount Fuji |

| Ordered: | 1894 |

| Builder: | Thames Iron Works, Blackwall, London |

| Laid down: | 1 August 1894 |

| Launched: | 31 March 1896 |

| Commissioned: | 8 August 1897 |

| Decommissioned: | 1923 |

| Reclassified: | 1 September 1922 as training hulk and barracks |

| Struck: | 1 September 1922 |

| Fate: | Scrapped 1948 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Fuji-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 12,230 long tons (12,430 t) (normal) |

| Length: | 412 ft (125.6 m) |

| Beam: | 73 ft (22.250400 m) |

| Draught: | 26 ft 3 in (8.0 m) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: | 2 shafts, 2 vertical triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range: | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 650 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

Fuji (富士) was the lead ship of the Fuji class of pre-dreadnought battleships built for the Imperial Japanese Navy by the British firm of Thames Iron Works in the late 1890s. The ship participated in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, including the Battle of Port Arthur on the second day of the war with her sister Yashima. Fuji fought in the Battles of the Yellow Sea and Tsushima and was lightly damaged in the latter action. The ship was reclassified as a coastal defence ship in 1910 and served as a training ship for the rest of her career. She was hulked in 1922 and finally broken up for scrap in 1948.

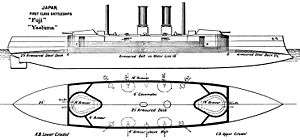

Design and description

Fuji was 412 feet (125.6 m) long overall and had a beam of 73 feet 6 inches (22.4 m) and a full-load draught of 26 feet (7.925 m). She normally displaced 12,533 long tons (12,734 t) and had a crew of 637 officers and enlisted men. The ship was powered by two Humphrys Tennant vertical triple-expansion steam engines using steam generated by ten cylindrical boilers. The engines were rated at 13,500 indicated horsepower (10,100 kW), using forced draught, and designed to reach a top speed of around 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). Fuji, however, reached a top speed of 18.5 knots (34.3 km/h; 21.3 mph) on her sea trials. She carried a maximum of 1,200 tonnes (1,200 long tons) of coal which allowed her to steam for 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[1]

The ship's main battery consisted of four 12-inch (305 mm) guns mounted in two twin gun turrets, one forward and one aft. The secondary battery consisted of ten 6-inch (152 mm) quick-firing guns, four mounted in casemates on the sides of the hull and six mounted on the upper deck, protected by gun shields.[2] A number of smaller guns were carried for defence against torpedo boats. These included fourteen 47-millimetre (1.9 in) 3-pounder guns and ten 2.5-pounder Hotchkiss guns of the same calibre.[Note 1] She was also armed with five 18-inch torpedo tubes. Fuji's waterline armour belt consisted of Harvey armour and was 14–18 inches (356–457 mm) thick. The armour of her gun turrets was six inches thick and her deck was 2.5 inches (64 mm) thick.[1]

Construction and career

Fuji, named after Mount Fuji,[5] was ordered as part of the 1894 Naval Programme and the ship was laid down by Thames Iron Works at their Blackwall, London shipyard on 1 August 1894.[6] The ship was launched on 31 March 1896 and completed on 17 August 1897.[7] The work was supervised by a team of over 240 engineers and naval officers from Japan, including future Prime Ministers Saitō Makoto and Katō Tomosaburō.[8] While fitting out at Portland, she participated in the fleet review marking Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee on 26 June 1897 at Spithead[8] before departing for Japan via the Suez Canal.[9]

In 1901, the ship exchanged 16 of her 47 mm guns for an equal number of QF 12 pounder 12 cwt[Note 2] guns. This raised the number of crewmen to 652 and later to 741.[1]

At the start of the Russo-Japanese War, Fuji, commanded by Captain Matsumoto Kazu,[10] was assigned to the 1st Division of the 1st Fleet. She participated in the Battle of Port Arthur on 9 February 1904 when Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō led the 1st Fleet in an attack on the Russian ships of the Pacific Squadron anchored just outside Port Arthur. Tōgō had expected his surprise night attack on the Russians by his destroyers to be much more successful than it actually was and expected to find them badly disorganized and weakened, but the Russians had recovered from their surprise and were ready for his attack. The Japanese ships were spotted by the Boyarin which was patrolling offshore and alerted the Russian defences. Tōgō chose to attack the Russian coastal defences with his main armament and engage the Russian ships with his secondary guns. Splitting his fire proved to be a bad idea as the Japanese 8-inch (203 mm) and six-inch guns inflicted very little significant damage on the Russian ships who concentrated all their fire on the Japanese ships with some effect. Although a large number of ships on both sides were hit, Russian casualties numbered only 17 while the Japanese suffered 60 killed and wounded before Tōgō disengaged. Fuji was hit by two shells during the battle that killed two and wounded 10 crewmen.[11]

On 10 March, Fuji and her sister Yashima, under the command of Rear Admiral Nashiba Tokioki, blindly bombarded the harbour of Port Arthur from Pigeon Bay, on the southwest side of the Liaodong Peninsula, at a range of 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi). They fired 154 twelve-inch shells,[12] but did little damage.[13] When they tried again on 22 March, they were attacked by Russian coast defence guns that had been transferred there by the new Russian commander, Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov, and also from several Russian ships in Port Arthur using observers overlooking Pigeon Bay. The Japanese ships disengaged after Fuji was hit by a 12-inch shell.[12]

Fuji participated in the action of 13 April when Tōgō successfully lured out a portion of the Pacific Squadron, including Makarov's flagship, the battleship Petropavlovsk. When Makarov spotted the six battleships of the 1st Division, he turned back for Port Arthur and Petropavlovsk struck a minefield laid by the Japanese the previous night. The Russian battleship sank in less than two minutes after one of her magazines exploded, Makarov one of the 677 killed. Emboldened by his success, Tōgō resumed long-range bombardment missions, which prompted the Russians to lay more minefields.[14]

During the Battle of the Yellow Sea in August 1904, Fuji was not hit because the Russian ships concentrated their fire on the leading ship of the column, Tōgō's flagship, the battleship Mikasa.[15] During the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905, she was hit a dozen times; the most serious of which penetrated the hood of the rear barbette, ignited some exposed propellant charges and killed eight men and wounded nine. After the ammunition fire was put out, the left gun in the barbette resumed firing and apparently fired the coup de grâce that sank the battleship Borodino.[16]

On 23 October 1908, Fuji hosted a dinner for the American Ambassador and the seniormost officers of the Great White Fleet during their circumnavigation of the world.[17] In 1910, her cylindrical boilers were replaced by Miyabara water-tube boilers and her main armament was replaced by Japanese-built guns. Fuji was reclassified as a first-class coast defence ship that same year, and was used for training duties in various capacities until disarmed in 1922.[18] She spent all of World War I based at Kure.[19] Her hulk continued to be used as a floating barracks and training center at Yokosuka until 1945.[18] Fuji was damaged by American carrier aircraft during their 18 July 1945 attack on Yokosuka[20] and capsized after the end of the war.[21] The ship was scrapped in 1948.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Sources differ significantly on the exact outfit of light guns. Naval historians Roger Chesneau and Eugene Kolesnik cite 20 three and four 2.5-pounders.[3] Jentschura, Jung & Mickel give a total of twenty-four 47 mm guns, without dividing them between the 3 and 2.5-pounders,[1] while Silverstone says that they had only twenty 47 mm guns, again without splitting them.[4]

- ↑ "cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight, 12 cwt referring to the weight of the gun.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 16

- ↑ Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 221

- ↑ Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 220

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 309

- ↑ Jane, p. 399

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 327

- 1 2 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 17

- 1 2 "Japanese visits to Portland recalled". Dorset Echo. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Hoare, p. 188

- ↑ Kowner, Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War, p. 223-224.

- ↑ Forczyk, pp. 24, 41–44

- 1 2 Forczyk, p. 44

- ↑ Brook, p. 269

- ↑ Warner & Warner, pp. 238–40

- ↑ Forczyk, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Campbell, p. 263

- ↑ "Tokio Enthusiasts Nearly Mob Sperry". New York Times. 24 October 1908. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- 1 2 Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Preston, p. 184

- ↑ Tully

- ↑ Fukui, p. 54

References

- Brook, Peter (1985). "Armstrong Battleships for Japan". Warship International. Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization. XXII (3): 268–82. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Forczyk, Robert (2009). Russian Battleship vs Japanese Battleship, Yellow Sea 1904–05. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978 1-84603-330-8.

- Fukui, Shizuo (1991). Japanese Naval Vessels at the End of World War II. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-125-8.

- Hoare, J.E. (1999). Britain and Japan, Biographical Portraits. III. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 1-873410-89-1.

- Jane, Fred T. (1904). The Imperial Japanese Navy. London, Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co. OCLC 1261639.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. Scarecrow. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tully, A.P. (2003). "Nagato's Last Year: July 1945 – July 1946". Mysteries/Untold Sagas of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Combinedfleet.com. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Warner, Denis; Warner, Peggy (2002). The Tide at Sunrise: A History of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905 (2nd ed.). London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5256-3.