John Boyd (military strategist)

| John Boyd | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Forty Second Boyd, Genghis John, The Mad Major, The Ghetto Colonel |

| Born |

January 23, 1927 Erie, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

March 9, 1997 (aged 70) West Palm Beach, Florida |

| Buried at | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Air Force |

| Years of service |

1945–1948 (Army Air Corps) 1951–1975 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars |

Korean War Vietnam War |

| Awards | Legion of Merit |

| Other work | Military strategist |

Colonel John Richard Boyd (January 23, 1927 – March 9, 1997) was a United States Air Force fighter pilot and Pentagon consultant of the late 20th century, whose theories have been highly influential in the military, sports, business, and litigation.

Early years

Boyd was born on January 23, 1927 in Erie, Pennsylvania. He graduated from the University of Iowa with a Bachelor's degree in economics[1] and later earned an additional bachelor's degree in industrial engineering from Georgia Tech.[2] Boyd enlisted in the Army Air Corps on October 30, 1944; he was a junior in high school. On March 27, 1953 Boyd arrived in Korea as an F-86 pilot.[3] Although Boyd was never credited with any kills, after his service in Korea he was invited to attend the most prestigious school a fighter pilot could attend, the Fighter Weapons School (FWS). Boyd attended the school and not only performed well, but rose to the top of his class. Upon graduation he was invited to stay at the FWS as an instructor. In Boyd’s time, being an instructor for the FWS was the most prized position any fighter pilot could hold. It was here that Boyd would revolutionize aerial tactics. His practice and teaching while at the FWS would sow early seeds for the later development of his concept of the OODA (observe, orient, decide, and act) loop.

Military career

As a high school graduate, Boyd enlisted in the United States Army and served in the Army Air Forces from 1945 to 1947, assigned as a swimming instructor in occupied Japan. After graduating from the University of Iowa, he served as a U.S. Air Force officer from July 8, 1951, until his retirement on August 31, 1975.[4] Boyd flew a short tour (22 missions instead of 100) in F-86 Sabres during the Korean War, during which he served as a wingman and never fired his guns or claimed an aerial kill.[5] Boyd was later assigned to the USAF Weapons School, where he became head of the Academic Section and wrote the tactics manual for the school.[5] Boyd was also brought to the Pentagon by Major General Arthur C. Agan, Jr. to do mathematical analysis that would support the McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle program in order to pass the Office of the Secretary of Defense's Systems Analysis process.[6]

He was dubbed "Forty Second Boyd" for his standing bet as an instructor pilot that beginning from a position of disadvantage, he could defeat any opposing pilot in air combat maneuvering in less than 40 seconds. According to his biographer, Robert Coram, Boyd was also known at different points of his career as "The Mad Major" for the intensity of his passions, as "Genghis John" for his confrontational style of interpersonal discussion, and as the "Ghetto Colonel" for his spartan lifestyle.[7]

Boyd died of cancer in Florida on March 9, 1997 at age 70. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery on March 20, 1997.[7][8]

Military theories

During the early 1960s, Boyd, together with Thomas Christie, a civilian mathematician, created the Energy-Maneuverability theory, or E-M theory of aerial combat. A legendary maverick by reputation, Boyd was said to have stolen the computer time to do the millions of calculations necessary to prove the theory,[9] though a later audit found that all computer time at the facility was properly billed to recognized projects and that no irregularity could be prosecuted. E-M theory became the world standard for the design of fighter aircraft. At a time when the Air Force's FX project (subsequently the F-15) was foundering, Boyd's deployment orders to Vietnam were canceled and he was brought to the Pentagon to re-do the trade-off studies according to E-M. His work helped save the project from being a costly dud, even though its final product was larger and heavier than he desired. However, cancellation of that tour in Vietnam meant that Boyd would be one of the most important air-to-air combat strategists with no combat kills. He had only flown a few missions in the last months of the Korean War (1950–1953), and all of them as a wingman.

With Colonel Everest Riccioni and Pierre Sprey, Boyd formed a small advocacy group within Headquarters USAF that dubbed itself the "Fighter Mafia".[10] Riccioni was an Air Force fighter pilot assigned to a staff position in Research and Development, while Sprey was a civilian statistician working in systems analysis. While assigned to working on the beginnings of the F-15, called the Blue Bird at the time, Boyd disagreed with the direction the program was going and proposed an alternative "Red Bird". This concept was for a clear weather, air-to-air only fighter with a top speed of Mach 1.6 and max 5 1/2G turn, seeing the Blue Birds Mach 2.5 and 9G as unnecessary and inefficient, they also wanted the aircraft to be devoid of radar. Boyd and Sprey both proposed this concept to Air Staff but there were no changes to the Blue Bird.[11]

Boyd was invited to Top Gun to brief the instructors on his "Energy Maneuverability" charts. Boyd's briefing did not go well. When Boyd insisted that it was impossible for the F-4 to win a dogfight against a MiG-17, the Top Gun instructors disagreed, two of them having shot down MiG-17s in combat. Commander Ron Mugs McKeown later said "Never trust anyone who would rather kick your ass with a slide rule than with a jet."[11]

The Secretary of Defense, attracted by the idea of a low cost fighter, gave funding to Riccioni for a study project on the LWF (Light Weight Fighter, which became the F-16). The DoD and Air Force both went ahead with the program, stipulating that it have a "design to cost" basis no more than 3 million per copy over 300 aircraft. The USAF considered the idea of a "Hi-lo" mix force structure and expanded the LWF program. The program soon went against the "Fighter Mafia's" idea: it was not to be the short ranged, low-tech, air-to-air aircraft they envisioned, but a medium-ranged, high-tech multi-role fighter-bomber.[11]

After his retirement from the Air Force in 1975, Boyd continued to work at the Pentagon as a consultant in the Tactical Air office of the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Program Analysis and Evaluation.

Boyd is credited for largely developing the strategy for the invasion of Iraq in the Gulf War of 1991. In 1981, Boyd had presented his briefing, Patterns of Conflict, to Dick Cheney, then a member of the United States House of Representatives.[12] By 1990, Boyd had moved to Florida because of declining health, but Cheney (then the Secretary of Defense in the George H. W. Bush administration) called him back to work on the plans for Operation Desert Storm.[13][14] Boyd had substantial influence on the ultimate "left hook" design of the plan.[15]

In a letter to the editor of Inside the Pentagon, former Commandant of the Marine Corps General Charles C. Krulak is quoted as saying "The Iraqi army collapsed morally and intellectually under the onslaught of American and Coalition forces. John Boyd was an architect of that victory as surely as if he'd commanded a fighter wing or a maneuver division in the desert."[16]

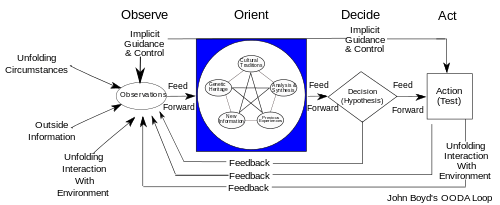

The OODA Loop

Boyd's key concept was that of the decision cycle or OODA loop, the process by which an entity (either an individual or an organization) reacts to an event. According to this idea, the key to victory is to be able to create situations wherein one can make appropriate decisions more quickly than one's opponent. The construct was originally a theory of achieving success in air-to-air combat, developed out of Boyd's Energy-Maneuverability theory and his observations on air combat between MiG-15s and North American F-86 Sabres in Korea. Harry Hillaker (chief designer of the F-16) said of the OODA theory, "Time is the dominant parameter. The pilot who goes through the OODA cycle in the shortest time prevails because his opponent is caught responding to situations that have already changed."

Boyd hypothesized that all intelligent organisms and organizations undergo a continuous cycle of interaction with their environment. Boyd breaks this cycle down to four interrelated and overlapping processes through which one cycles continuously:

- Observation: the collection of data by means of the senses

- Orientation: the analysis and synthesis of data to form one's current mental perspective

- Decision: the determination of a course of action based on one's current mental perspective

- Action: the physical playing-out of decisions

Of course, while this is taking place, the situation may be changing. It is sometimes necessary to cancel a planned action in order to meet the changes. This decision cycle is thus known as the OODA loop. Boyd emphasized that this decision cycle is the central mechanism enabling adaptation (apart from natural selection) and is therefore critical to survival.

Boyd theorized that large organizations such as corporations, governments, or militaries possessed a hierarchy of OODA loops at tactical, grand-tactical (operational art), and strategic levels. In addition, he stated that most effective organizations have a highly decentralized chain of command that utilizes objective-driven orders, or directive control, rather than method-driven orders in order to harness the mental capacity and creative abilities of individual commanders at each level. In 2003, this power to the edge concept took the form of a DOD publication "Power to the Edge: Command ... Control ... in the Information Age" by Dr. David S. Alberts and Richard E. Hayes. Boyd argued that such a structure creates a flexible "organic whole" that is quicker to adapt to rapidly changing situations. He noted, however, that any such highly decentralized organization would necessitate a high degree of mutual trust and a common outlook that came from prior shared experiences. Headquarters needs to know that the troops are perfectly capable of forming a good plan for taking a specific objective, and the troops need to know that Headquarters does not direct them to achieve certain objectives without good reason.

In 2007, strategy writer Robert Greene discussed the loop in a post called "OODA and You".[17] He insisted that it was "deeply relevant to any kind of competitive environment: business, politics, sports, even the struggle of organisms to survive", and claimed to have been initially "struck by its brilliance".

The OODA Loop has since been used as the core for a theory of litigation strategy that unifies the use of cognitive science and game theory to shape the actions of witnesses and opposing counsel.[18]

Aerial Attack Study

Boyd also served to revolutionize air-to-air combat in that he was the author of the Aerial Attack Study. The Aerial Attack Study became the official tactics manual for fighter aircraft. Boyd changed the way pilots thought; prior to his tactics manual, pilots thought that air-to-air combat was far too complex to ever be fully understood. With the release of Boyd’s Aerial Attack Study, pilots realized that the high-stakes death dance of aerial combat was solved.[19] Boyd said that a pilot going into aerial combat must know two things: the position of the enemy and the velocity of the enemy. Given the velocity of an enemy, a pilot is able to decide what the enemy is capable of doing. When a pilot knows what maneuvers the enemy can perform, he can then decide how to counter any of the other pilot’s actions. The Aerial Attack Study contained everything a fighter pilot needed to know.[20]

Aside from the overwhelming belief in the Air Force that air-to-air combat was a thing of the past, Boyd proved that it was very much alive. The Air Force was moving away from aerial combat because of development in missiles. Boyd proved in his Aerial Attack Study that the art of the dogfight was not dead by showing that fighter pilots could out-maneuver missiles. John Boyd’s Aerial Attack Study was revolutionary because it was the first instance in history in which tactics were reduced to an objective state.[21] Boyd’s manual proved that he was the undisputed master in the area of aerial combat. Within a decade the Aerial Attack Study became the text for air forces around the world.

Foundation of theories

Boyd never wrote a book on military strategy. The central works encompassing his theories on warfare consist of a several hundred slide presentation entitled Discourse on Winning & Losing and a short essay entitled "Destruction & Creation" (1976).[22]

In Destruction & Creation, Boyd attempts to provide a philosophical foundation for his theories on warfare. In it he integrates Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem, Heisenberg's Uncertainty principle, and the Second Law of Thermodynamics to provide a context and rationale for the development of the OODA Loop.

Boyd inferred the following from each of these theories:

- Gödel's Incompleteness Theorem: any logical model of reality is incomplete (and possibly inconsistent) and must be continuously refined/adapted in the face of new observations.

- Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle: there is a limit on our ability to observe reality with precision.

- Second Law of Thermodynamics: The entropy of any closed system always tends to increase, and thus the nature of any given system is continuously changing even as efforts are directed toward maintaining it in its original form.

From this set of considerations, Boyd concluded that to maintain an accurate or effective grasp of reality one must undergo a continuous cycle of interaction with the environment geared to assessing its constant changes. Boyd, though he was hardly the first to do so, then expanded Darwin's theory of evolution, suggesting that natural selection applies not only in biological but also in social contexts (such as the survival of nations during war or businesses in free market competition). Integrating these two concepts, he stated that the decision cycle was the central mechanism of adaptation (in a social context) and that increasing one's own rate and accuracy of assessment vis-a-vis one's counterpart's rate and accuracy of assessment provides a substantial advantage in war or other forms of competition. The key to survival and autonomy is the ability to adapt to change, not perfect adaptation to existing circumstances. Indeed, Boyd noted that radical uncertainty is a necessary precondition of physical and mental vitality: all new opportunities and ideas spring from some mismatch between reality and ideas about it, as examples from the history of science, engineering and business illustrate.

Elements of warfare

Boyd divided warfare into three distinct elements:

- Moral Warfare: the destruction of the enemy's will to win, disruption of alliances (or potential allies) and induction of internal fragmentation. Ideally resulting in the "dissolution of the moral bonds that permit an organic whole [organization] to exist." (i.e., breaking down the mutual trust and common outlook mentioned in the paragraph above.)

- Mental Warfare: the distortion of the enemy's perception of reality through disinformation, ambiguous posturing, and/or severing of the communication/information infrastructure.

- Physical Warfare: the abilities of physical resources such as weapons, people, and logistical assets.

Military reform

John Boyd's briefing Patterns of Conflict provided the theoretical foundation for the "defense reform movement" (DRM) in the 1970s and 1980s. Other prominent members of this movement included Pierre Sprey, Franklin C. Spinney, William Lind, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Operational Testing and Evaluation Thomas Christie, Congressman Newt Gingrich, and Senator Gary Hart. The Military Reform movement fought against what they believed were unnecessarily complex and expensive weapons systems, an officer corps focused on the careerist standard, and over-reliance on attrition warfare. Another reformer, James G. Burton, disputed the Army test of the safety of the Bradley fighting vehicle. James Fallows contributed to the debate with an article in The Atlantic Monthly titled "Muscle-Bound Superpower", and a book, National Defense. Today, younger reformers continue to use Boyd's work as a foundation for evolving theories on strategy, management and leadership.

Boyd gave testimony to Congress about the status of military reform after Operation Desert Storm.[23]

Maneuver warfare and the Marines

In January 1980 Boyd gave his briefing Patterns of Conflict at the U.S. Marines AWS (Amphibious Warfare School). This led to the instructor at the time, Michael Wyly, and Boyd changing the curriculum, with the blessing of General Trainor. Trainor later asked Wyly to write a new tactics manual for the Marines.[24] John Schmitt, guided by General Alfred M. Gray, Jr. wrote Warfighting, during the writing, he collaborated with John Boyd. Wyly, Lind, and a few other junior officers are credited with developing concepts for what would become the Marine model of maneuver warfare.

Wyly, along with Pierre Sprey, Raymond J. "Ray" Leopold, Franklin "Chuck" Spinney, Jim Burton, and Tom Christie were described by writer Coram as Boyd's Acolytes,[25] a group who, in various ways and forms, promoted and disseminated Boyd's ideas throughout the modern military and defense establishment.

References

Notes

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 103.

- ↑ Coram 2002, p.49

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 312.

- 1 2 Michel 2006, p. 297.

- ↑ Michel 2006, pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 Hillaker, Harry. "Tribute To John R. Boyd." Code One Magazine, July 1997.

- ↑ John Richard Boyd at Find a Grave

- ↑ Coram, Robert. "Interview (Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed The Art of War)" Span video. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- ↑ Burton 1993

- 1 2 3 https://etd.auburn.edu/bitstream/handle/10415/595/MICHEL_III_55.pdf

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 355.

- ↑ Coram 2002, pp. 422–24.

- ↑ Ford 2010, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Wheeler and Korb 2007, p. 87.

- ↑ Hammond 2001, p. 3.

- ↑ Greene, Robert. "OODA and You." Power, Seduction and War: The Blog of Robert Greene. Retrieved: September 7, 2011.

- ↑ Dreier 2012, pp. 74–85.

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 114

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 115

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 116

- ↑ http://www.goalsys.com/books/documents/DESTRUCTION_AND_CREATION.pdf

- ↑ Schwellenbach, Nick. "Air Force Colonel John Boyd's 1991 House Armed Services Committee Testimony." U.S. Project On Government Oversight, March 26, 2011. Retrieved: September 7, 2011.

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 382.

- ↑ Coram 2002, p. 182.

Bibliography

- Boyd, John Richard (September 3, 1976), Destruction and Creation (PDF), US Army Command and General Staff College.

- Burton, James G (1993), The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 1-55750-081-9.

- Coram, Robert (2002). Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War (biography). New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-31679-688-0.; contains "Destruction and Creation".

- Dreier, AS (2012). Strategy, Planning & Litigating to Win. Boston, Massachusetts: Conatus. ISBN 978-0-615-67695-1. Uses the OODA Loop as a core construct for a litigation strategy system unifying psychology, systems theory, game theory and other concepts from military science.

- Ford, Daniel (2010), A Vision So Noble: John Boyd, The Ooda Loop, and America's War on Terror, Greenwich, London: Daniel Ford, ISBN 1-4515-8981-6.

- Hammond, Grant T (2001). The Mind of War: John Boyd and American Security. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-941-7. An explanation of Boyd's ideas.

- Henrotin, Joseph (2005). L'Airpower au 21ème siècle: Enjeux et perspectives de la stratégie aérienne [Airpower in the 21st century: interplay & perspectives of aerial strategy]. Réseau multidisciplinaire d'études stratégiques (in French). 1. Bruxelles: Bruylant (RMES). ISBN 2-8027-2091-0. Perhaps the best book on air strategy. Widely details John Boyd's theories.

- Lind, William S. (1985). Maneuver Warfare Handbook. Westview Special Studies in Military Affairs. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 0-86531-862-X. Based on John Boyd's theories.

- Warfighting (PDF), Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication (1), Washington, D.C.: United States Marine Corps, 1997 [1989].

- Michel, Col. Marshall (2006), The Revolt of the Majors: How the Air Force Changed After Vietnam (and Saved the World) (PDF), Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Security Studies Program.

- Osinga, Frans (2007). Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-37103-1. Aims to provide a better understanding of Boyd's ideas concerning conflict and military strategy. Contains a full description and explanation of all of his presentations. Takes reader beyond rapid OODA loop idea and demonstrates direct influence on development of Network Centric Warfare and Fourth Generation Warfare. Argues Boyd is first postmodern strategist.

- Richards, Chester W (2004). Certain To Win: The Strategy of John Boyd, Applied To Business. Philadelphia: Xlibris. ISBN 1-4134-5377-5. Develops the strategy of the late US Air Force Colonel John R. Boyd for the world of business.

- Wheeler, Winslow T; Korb, Lawrence J (2007), Military Reform: A Reference Handbook (illustrated ed.), Santa Barbara, California: Praeger Security, ISBN 0-275-99349-3.

External links

- Correll, John, "The Reformers", Air Force Magazine (online ed.).

- Cowan, Jeffrey, From Air Force Fighter Pilot to Marine Corps Warfighting, Defense in the National Interest, DNI pogo.

- Richards, Chet, Colonel John R. Boyd, USAF, Briefings, Air Power Australia.

- Spinney, Chuck (early 1999), Defense and the National Interest (archive the commentaries of defense analyst [and Boyd "acolyte"]),

[W]e have the complete works of the late military theorist, Col John Boyd, USAF.

Check date values in:|date=(help) - Brian, Danielle (March 1999), "Defense and the National Interest", Project On Government Oversight (collection of [Boyd "acolyte"] Chuck Spinney’s commentaries on the foibles of our defense program), The Project on Government Oversight, archived from the original on November 24, 2009.

- Boyd, Writings, DNI Pogo.

- Coram, Robert (January 26, 2003), "Booknotes", Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War (interview).

- "John Boyd", Intellipedia, Intelink.