Karava

|

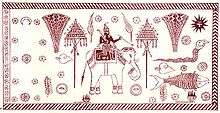

The Karava Maha Kodiya or main flag of the Karava Community. It depicts several traditional royal symbols. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sri Lanka, | |

| Languages | |

| Sinhala, Marathi | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sinhalese, Tamils, Karaiyar, Kshatriyas, Kurukulams, Kauravas |

Karava (pronounced Karaava) also Karave, Kara, Karavaa, Kaurava is a significant Sinhalese community from the Island of Sri Lanka. The Tamil equivalent is Karaiyar.

General

The first recorded instance is the Abhayagiri vihara terrace inscription dating from the 1st century BC denoting a Karava navika.[1]

The origins of the term Karava are still debated. One school of thought maintains that the Karava are the traditional coastal folk citing the similarity between the terms for sea-water (Kara Diya in Sinhalese) and Tamil Karaiyar denoting 'coast men'.[2] Another contends that it was the traditional military or warrior caste of Sri Lanka. Although no specific mention of such a caste is extant in pre-colonial literature, there is mention of Kshatriya, foreign warriors and mercenaries throughout history.[3][4][5][6][7]

Historical manuscripts such as the Mukkara Hatana indicate that there were also several migrations from India including the Kuru Mandalam Coromandal coast of South India.[1][6][8][9] The Aluth (new) and Parana (old) Kuru korales (provinces) denote such cultural acknowledgement and royal patronage. Many Karava communities throughout Sri Lanka claim an ultimate origin from the Kuru (kingdom) and the epic Kauravas of the Mahabharata.

The Karavas came into contact with the Portuguese, Dutch and English colonial powers before the rural interiors and assimilated (through choice or force) with regards to education, dress, religion and customs and exploited the new opportunities in commercial enterprise earlier than other communities. The Karavas were the most successful at this as all communities strove to modernise and still do.[10][11] The Karavas north of Negambo, along with all other Sinhalese communities are mostly Catholics, the Karavas south of Colombo along with other Sinhala speakers and are mostly Buddhists. With Salagama and Durave, they make a sizeable number of people among the coastal Sinhalese sub group.

Traditional status

The Karavas were the traditional fisher-folk,[12] naval warriors[2][6][13] seafaring merchants,[1][14][15] coastal chieftains[16][17] and regional kings[3][4][5][18][19] as well as craftsmen[14][20] and even some farmers of the Sri Lankan coast, including the producers of salt, which is a foundation of civilization.[21] Also, it was our kings who were among the first to convert to Christianity; Prince Jugo Bandara,[22] Don Juan Dharmapala Peria Bandara, Don Phillip Yamasingha Bandar, Mahapatabandige Donna Catherina Kusumasanadevi, Don John Wimaladharmasurya,[23][24][25] Prince Dom Afonso,[26] Dom João, Dom Luis and Dom Philip Nikapitiye Bandara.[27] The clan has also claimed to be the naval and military caste of Sri Lanka and were also mercenaries to kings in India and Sri Lanka.[2][4][5][6][18][13][28] Their chiefs were referred to as Patabenda in Sinhala and Patangatim in Tamil, lived in the coast and ports of Sri Lanka[16][17][28] Although conclusive evidence is lacking that they were the ruling class of the medieval era, there are historical records including Brahmi rock inscriptions, sword appointments and documents such as the 'Pujavaliya', 'Rajaveliya', 'Mukara Hatana' and Portuguese state records that suggest their importance to the rulers.[18][28][29][30]

All major Karava settlements traditionally had service castes such as barbers, drummers, potters, dhobies, etc. settled in satellite communities around them. The presence of such settlements is still evident despite the social changes and inter-caste migrations of the past century.

Heraldry

The Karavas were one of the few Sri Lankan communities traditionally entitled to use flags. British Government Agents studying Sri Lankan flags have noted that not a single flag could be found even in the residences of Kandyan chiefs as even they were not entitled to use flags. These observations, made in the 19th Century (after 1815), do take into account that the Kandyans were living under a Sinhala Royal dominion that reserved the right to bear flags to the Palace. At the same time, clans and families of most other caste groups in the lowlands did not bear flags, whilst the Karava of the Kandyan province such as in Thamankaduwa were entitled to it.[31] It is also certain that these flags depicting royal emblems existed before the archaeological excavations of Anuradhapura began in the latter part of the British and post British era, substantiating many of the depictions. A large number of these Karava flags have survived the ravages of time and many are illustrated in E. W. Perera’s book Sinhalese Banners and Standards.

Though the origin of the term 'Royal Insignia' is hotly debated subject and passed off as a modern affectation of gentility, it is certain that these insignia of royal emblems existed before the archaeological excavations of Anuradhapura began in the latter part of the British and post British era and that even the Kandyan kings made an exception to allow the Karavas its use, substantiating them.[31] The symbolic use of the conch shell in all things sacred and regal cannot be denied, so too was the tying of the royal forehead plate; Nalapata because they are mentioned in the 'Rajavaliya'. Ancient rock inscriptions, copper plates & coin engravings are now available trough archaeological excavations depicting the emblems of the ruling dynasty. These customs are common to all regions of South Asia and beyond, not just Sri Lanka (whose royal dynasties, language and religions originate mostly from India in any case) and scientifically valid. Likewise the sun and the moon, pearl umbrella are traditional royal items in Sri Lanka's past and throughout the region.[32][33]

For the past 1,700 years the sacred Tooth Relic of Gautama Buddha was a possession of the ruling king/dynasty of that period, whosoever possessed this was acknowledged as the rightful ruler of Lanka and whoever won the throne usually came to possess it. Upon each change of capital, a new palace was built to enshrine the Relic. Finally, in 1591 it was brought to Kandy where it is at present, in the Temple of the Tooth. Contrary to the current practice, the tooth relic is not exclusive to a few privileged persons or the male gender as that tarnishes the doctrine of Buddhism and becomes a tool of oppression. Even if we overlook that some royalty stemmed from this Suryawamsa warrior/mercenary community,[2][6][34] what is certain is that the Abhayagiri vihāra was the early custodian of the Tooth Relic[35] and the Karava Navika, Kuvera (merchant) Sujatha, Illa (Hela) Bharta and Thissa (King/Prince) held positions of distinction & privilege in that Viharaya.[1] Their patronage of the Sanga, monasteries and facilitating the propagation of the Dharma, pilgrimage, relics, mercantile and military activity in ancient times is well documented in caves, monastires and family traditions[29][36]

The possession of the tooth relic alone was however not sufficient for the general turned king; Don John Wimaladharmasurya, but the 'royalty' of Mahapatabandige Donna Catherina Kusumasanadevi. Additionally, there had been many instances in history where there had been several simultaneous kingdoms, the 'rightful' not possessing the 'Tooth', while many not so 'rightful' had ruled, e.g., Rajarata-Ruhuna-Dakkhinadesa, Kashyapa-Mogallana, Alakeshwara-Buwanekabahu V, Kotte-Sitawaka-Kandy, colonial. Even in the land-locked Kandyan kingdom 'Unambuwe' a son of a concubine of some considerable background from the vicinity of the 'Tooth' was deemed not of 'royalty', hence a Tamil of royalty was imported from Madurai. This last Kandyan royal dynasty (four kings) of Nayake origin was from the Balija caste.

The oldest Buddhist sect in Sri Lanka, the Siam Nikaya (estd. 19 July 1753) are the current custodians of the Tooth Relic. As of 1764, the Siyam Nikaya controversially restricted higher ordination only to the Radala and Govigama castes, Sitinamaluwe Dhammajoti (Durava) being the last nongovigama monk receive its Higher ordination. This conspiracy festered within the Siyam nikaya itself, where Moratota Dhammakkandha, Mahaayaka of Kandy, with the help of the last two Kandyan Tamil kings took possession of the Siri Paadha shrine and the retinue villages from the low country Mahanayaka Karatota Dhammaranma and appointed a rival.[37] After the 1764 conspiracy and other factors[38][39] there was less of an incentive for change, though the Karava and other minority communities of the Island spent a fortune renovating ancient Temples and playing a prominent role reviving Buddhism in the past two centuries.[40][41][42][43][44] It was Ven. Dodanduwe Piyaratana Tissa Thera who was conferred the Honorary membership of the Theosophical Society in 1878 that encouraged Colonel Henry Steel Olcott to visit Ceylon in 1880.[45][46] The famous Panadura debate was held between Buddhist and Christian establishments of related (Karava) families of Panadura.

Apart from flags, the Karavas were the only community in Sri Lanka entitled to the use of the said 'royal insignia'. Insignia such as the pearl umbrella, flags, swords, trident, yak tail whisks, lighted flame torches and drums were previously widely used by the Karavas at their weddings and funerals. By the 1960s, such usage was now greatly reduced but even now it is not unusual to see these royal symbols used even at funerals of extremely impoverished Karavas.[31]

With the fall of Sri Lankan kingdoms under Dutch and British colonialism the Karavas kept to their occupations such as deep sea fishing, cultivation, and trading for survival.

Social position

The Karave community of today is made up of many Clans as indicated by their hereditary ancestral names also known as "Ge" names and Clan names. In Sri Lanka they are an influential and prominent caste among the majority Sinhalese. They are now said to be behind the majority Govigama. Most Karave were converted to the Catholic religion during the Portuguese period. (See Patabendige for Portuguese conversion strategies). During the British period several Karava families, along with families from other communities achieved elite status by participating in the colonial economic activities. Although the strides made thus far by a few families are impressive, and many members of the community are leading professionals and businessmen, a great many of them now languish at the bottom of the economic order, deprived of opportunities for progress .

Ancestral names

Gé names among the Sinhala speaking population are traditional hereditary family names. They denote a person's ancestry, caste, social status of an illustrious ancestor or the village of origin. The Karava traditionally used the title or clan name before the 18th century emergence of the govi. Hence, 'Patabandi' became 'Patabadige'. These names predate the 16th century European colonisation of Sri Lanka. Gé names precede an individual’s personal name unlike a surname which follows one’s personal name. As such it is important to understand the historical significance of these ancient Ge’ names vis-à-vis the 20th century British period acquired surnames. The Karavas Ge’ names overwhelmingly show a traditional military, royal or marine heritage. Some of the more frequently encountered Karava Ge names are given below. Some members of the Karava caste descend from an Iberian ancestor, dating back to the 16th century, as it is known that the Portuguese, mostly men, were ordered to marry local women everywhere in the Portuguese empire. In those cases they also use, apart from Ge names, their Iberian-derived surnames such as De Silva, De Mel, Fernando, Perera, Mendis, Almeida, De La Salle, De Mazenod, Peris. In many instances the use of a Portuguese surname also resulted from conversion along with many kings and aristocrats of the period. In later periods even some interior rural folk adopted these names for upliftment similar to the adoption of English first names by the many urban folk during the British period.

Names based on leadership or military activity include Aditya (Suryawamsa king/chief/noble), Arasanilayitta[29] (Regent (possessing royal authority)), Arasa Marakkalage (house of the Royal Mariners), Patabendige (house of the local headmen. 'Pata' in this name refers to a golden plate that this clan was wearing to denote their royal status[17]), and Thantrige (also Thanthrige, Tantulage, Thanthulage) (house of experts, as in Veditantrige).

Names based on profession include Marakkalage (house of the ship/boat owners or sailors) and Vaduge (also Baduge; house of carpenters, ship & boat builders, also descendant of Vadugar as in Bala-Appu Vaduga.[2]).

Other names based on tribe or clan

Often, Karavas in Sri Lanka belong to one or more of the Suriya clans Weerasuriya, Jayasuriya, Balasuriya, Wickramasuriya, Kurukulasuriya, Warnakulasuriya, Mihindukulasuriya, Bharathakulasuriya, Manukulasuriya, Vijayakulasuriya or Arasakulasuriya which appear to indicate distinct streams of migrations or clans loyal to distinct Kings. Other clans are Vadugas, Koon Karavas (such as Samarakoon, Weerakoon etc.), Konda Karavas (such as WeeraKonda, Konda Perumal Árachchigé etc.) and rarer clans such as Olupathage.

Some examples of clan names are:

- Aditya: Denotes a suryawamsa king found throughout India, but exclusive to the Karavas in Sri Lanka, recorded as Ditta, Adicca or Arittha in some ancient texts. (The first royal dynasty of the similar linguistic culture to the Sinhalese,[47] from the thousand cluster islands; the Maldives, was Aditya

- Arasanilayitta: Possessing kingly status

- Kurukula (Suriya): Descending from the Kuru clan

- Varnakula Suriya: God Varuna Sea God[48][49][50](alternately Colour-Caste)

Notables

- Agga Maha Pandita Polwatte Buddhadatta Mahanayake Thera: Sri Lanka's first Scholar Monk to receive 'Agga Maha Pandita'

- Amaradeva, Pandit: The Legend of 'Sinhala Classical' music (vocalist/composer/instrumentalist), the creator of the Sinhala Art Song, Padma Shri, Deshamanya and Ramon Magsaysay Award recipient

- Aravinda De Silva: Legendary Batsman (Cricketer)

- C T Fernando: Legendary musician/singer/composer

- Celestina Dias: Premier lady entrepreneur and philanthropist

- Chaminda Vaas: Legendary Bowler (Cricketer)

- Charles Henry de Soysa: Pre-eminent entrepreneur and philanthropist

- Clancy Fernando - Admiral: Ex- Commander of the Navy

- Chinthaka De Soyza: Former SAARC 100 meters record holder

- Dombagasare Sri Sumedankara Thera: Discoverer and restorer of the ancient Seruvila Mangala Raja Maha Viharaya[51][52]

- Dodanduwe Piyaratana Tissa Nayaka Thera: the founder of the first Buddhist school in Sri Lanka and the initiator of Olcott's Buddhist revival through Buddhist schools[45][46][53]

- Ediriweera Sarachchandra: Ramon Magsaysay Award winning playwright, poet and social commentator

- Frank Marcus Fernando, 3rd Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Chilaw

- G. L. Peiris - Prof.: Former Cabinet Minister of External Affairs.

- Gratien Fernando - Bombardier : Anti-colonial agitator

- Harold de Soysa, first indigenous Anglican Bishop of Colombo

- Henry Woodward Amarasuriya: Pioneer entrepreneur, philanthropist and politician

- James Peiris : National Hero (Independence), First Ceylonese Governor (Acting), elected Vice President of the Legislative Council of Ceylon & the World's First non-European President of the Cambridge (or even Oxford) Union.

- Jaliya Wickramasuriya Former Ambassador to the United States and Mexico.[3]

- Jayalath Weerakkody - Air Marshal : Ex- Air Force Commander

- Lakdasa De Mel: Archbishop of India, Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon

- Latha Walpola: Hela Gee Rejina / Nightingale of Sri Lanka[54]

- Leslie Goonewardena: Independence Activist and Co-Founder of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party

- Lester James Peiris: Father of Sinhala Cinema (Sri Lankabhimanya recipient)

- Malini Fonseka: The Queen of Sinhala Cinema

- Marcelline Jayakody - Fr. : Catholic priest, musician, lyricist, author & Ramon Magsaysay Award & Kalasuri recipient

- Martin Wickramasinghe: The father of modern Sinhala literature / Island's Favorite Novelist

- Patrick de Silva Kularatne: Legendary educationist

- Rohana Wijeweera: Founding leader of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna.

- Ronnie De Mel: Ceylon Civil Service (CCS),Cabinet Minister and current Senior Presidential adviser.

- Royce de Mel, 1st native Commander of the Sri Lanka Navy

- Sanath Jayasuriya: Legendary All-Rounder (Cricketer)

- Sarath Fonseka : Former Commander of the Sri Lanka Army and former candidate for President of Sri Lanka[55]

- Susantha de Fonseka: Pioneer diplomat and independence activist

- Tissa Balasuriya, Catholic priest

- Tyronne Fernando: Cabinet Minister,Presidential adviser and Former Governor of the North Eastern Province

- Veera Puran Appu: Sinhala Hero who fought against the British.

- Warnakulasurya Wadumestrige Devasritha Valence Mendis, 4th Bishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Chilaw

- Weligama Sri Sumangala: Scholar Monk, Buddhist Revivalist & educationalist

See also

- Caste in Sri Lanka

- Bharatakula

- Negambo Tamils

- Sinhalisation

- Kastane

- Lascarins

- Timeline of the Karavas

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vaduga: Sri Lanka and the Maldive Islands, By Chandra Richard De Silva, p.111 & 137

- 1 2 3 King Bhatiyatissa: The Chieftains of Ceylon, J. C. Van Sanden, p.32

- 1 2 3 Kurukulattaraiya, the prince with the golden anklet: Epigraphica Indica – Vol. 21, part 5, No.38, p.220-50

- 1 2 3 Prince Kurukulattaraiya, Vijayabahu the Great's commander: The Karava of Ceylon, M.D.Raghavan, p.9-10

- ↑ Portuguese Encounters with Sri Lanka and the Maldives by Chandra Richard De Silva, p.137

- ↑ Fernando, Dr. Granville. "Hail Chilaw, my home town!". Archived from the original on 2002-02-20.

- ↑ Warfare in Pre-British India – 1500BCE to 1740CE By Kaushik Roy, p.164-9

- ↑ Nobodies to Somebodies: The Rise of the Colonial Bourgeoisie in Sri Lanka review by Chandra R. de Silva, Retrieved 2016-01-11

- ↑ When the 'nobodies'made their mark sundaytimes.lk Retrieved 2016-01-11

- ↑ Beyond Price: Pearls and Pearl-fishing : Origins to the Age of Discoveries, Volume 224 By R. A. Donkin, p.60-5..

- 1 2 The naval encounters of Prince of Ouva, Kuruwita Rala (under nephew Pedro Baretto)

- 1 2 Nobodies to Somebodies: The Rise of the Colonial Bourgeoisie in Sri Lanka, Kumari Jayawardena, pp. 35, 72 & 200 (Zed) ISBN 9781842772287

- ↑ Coastal Trade: Ceylonese Participation in Tea Cultivation, Maxwell Fernando: History of Ceylon Tea Website, Accessed 1 November 2016

- 1 2 Patangatin/Headmen of Chilaw baptised in 1606 at Malwana; Ceylon and the Portuguese 1505-1658, by Paulus Edward Pieris

- 1 2 3 Royal grant to a port Patangatin, Kingdom of Jaffanapatam, P.E. Pieris, p. 25-28

- 1 2 3 Kuruwita Rala appointed guardian of the heirs to the throne: An historical, political, and statistical account of Ceylon..., Volume 1, By Charles Pridham , p. 109-11

- ↑ Buvanekabahu VI and Parakramabahu VIII: Portuguese encounter with King of Kotte in 1517by A. Denis N. Fernando (The Island 2006/Lankalibrary web)

- ↑ A collection of traditional masks

- ↑ Fa-Hsien's account, Mesolithic & Iron Age Culture...; Pre-Vijayan Agriculture in Sri Lanka, Prof. T. W. Wikramanayake

- ↑ "Catholic Church in Sri Lanka - A History in Outline by W.L.A.Don Peter - The Portuguese Period". Xoomer.virgilio.it. 1999-08-23. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ↑ "Don Phillip, Don John and Dona Catherina of Sri Lanka". Lankalibrary.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ↑ "Midwee05". Infolanka.com. 2002-03-06. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ↑ "Sri Lankan Politics in Foucs". www.manthree.com. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- ↑ History of Trincomalee

- ↑ Dr. K. D. Paranavitana (2007-07-22). "A church in Lisbon and the Black Prince of Lanka". Sundaytimes.lk. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- 1 2 3 Young Bhuvenaka Bahu & Raigam Bandara under the care of the Patabenda (of Yapapatuna); Rajavaliya, Or, a Historical Narrative of Sinhalese Kings, B. Guṇasēkara, p. 75 ISBN 8120610296

- 1 2 3 The sword of Mahanaga Rajasinghe Kuruvira Adithya Arsanilaishta (1416 AD) - the oldest representation of the Makara knuckle-guard: Ancient Swords, Daggers and Knives in Sri Lankan Museums, P.H.D.H. De Silva and S. Wickramasinghe, pp.82,90,101-5 (National Museums of Sri Lanka) ISBN 9789555780216

- ↑ Karava Dissavas of the Kandyan Kingdom; Tri Sinhala: The Last Phase, 1796-1815, P. E. Pieris, p.77 (Asian Educational Services) ISBN 9788120615588

- 1 2 3 In 1574 the Mahapatabenda of Colombo is beheaded and quartered by the Portuguese for treasonable communication with Mayadunne, the sannas grants of king Mayadenne to Sitavaka Tantula and Rajapakse Tantula of Ambalangoda for serving the interests of Sitawaka kings, Thamankaduwa, Diddeniya, Galagamuwa and Matale Karavas and their insignia The Karāva of Ceylon: Society and Culture, M. D. Raghavan pp.33-6,43,66,71-5 (K.V.G. De Sīlva ) ASIN: B0006CKOV2

- ↑ Royal emblems and Lord Buddha

- ↑ Mutukuda (Pearl-Umbrella) from local sources

- ↑ Sapumal Kumaraya/Bhuvanekabahu VI

- ↑ Abode of the Sacred Tooth Relic

- ↑ The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia, by Himanshu Prabha Ray, pp. 15, 118-9, 132, 141, 148, 233, 254, 258, 267, 287 & 340

- ↑ Buddhism in Sinhalese Society, 1750-1900: A Study of Religious Revival and.... By Kitsiri Malalgoda, p. 84-87 & 91

- ↑ Life of Jesus of Nazareth: born in Bethlalem, grew up in Egypt, (visited India?) & worked in the Middle East

- ↑ Joseph Vaz and Gonsalves lived, worked and died in this country - Blessed Joseph Vaz, a missionary model for all time, Rajtilak Naik (The Times of India)

- ↑ Lanka's Buddhist resurgence - Within a span of over a hundred years Archaeological restorations of several Buddhist sites took place; Stupas at Tissamaharamaya (1908), Seruvila (1922) and others followed Fragrance of a Buddha Jayanthi - Upali SALGADO (Daily News)

- ↑ Swarnamali Maha Seya and the forgotten monk - Upali K Salgado (The Island)

- ↑ Poson Day Historic Reflections and Buddhist Activity in the Colonial Time - Upali K Salgado (The Island)

- ↑ Mrs. Jeremias Rodrigo-Dias: A visionary of the 20th Century - Dr. Ganga de Silva (The Island)

- ↑ 113th Birth Anniversary : Sir Bennet and Lady Sarah Soysa - the philanthropists of the hills by M. B. Dassanayake (Daily News)

- 1 2 Colonel Henry Steele Olcott was invited to Ceylon by his friend Ven. Dodanduwe Piyaratana Tissa Thera: That controversial clash, by D. C. Ranatunga

- 1 2 It was primarily due to the persuasion of Ven. Dodanduwe Piyarathana Thera that Colonel Henry Steele Olcott took an interest in the revival of Buddhist Education in Sri Lanka.: 'The first Buddhist School in Sri Lanka - Piyarathana Vidyalaya of Dodanduwa dilapidated, threatened with closure' by W. T. J. S. Kaviratne (Daily News)

- ↑ Maritime Archaeology: Australian Approaches edited by Mark Staniforth, Michael Nash, p. 100 Maldives settled by Lankans

- ↑ Heaven, Heroes, and Happiness: The Indo-European Roots of Western Ideology By Shan M. M. Winn, p.83

- ↑ Indra replaces Varuna as Chief of the Vedic pantheon Ancient Indian History and Civilization By Sailendra Nath Sen, pp.48-9

- ↑ Varuna faded away with the ascendancy of Shiva and Vishnu, Encyclopedia Mythica by Stephen T. Naylor

- ↑ http://www.dailynews.lk/2003/09/08/new28.html

- ↑ http://www.sundayobserver.lk/2009/05/03/spe04.asp

- ↑ The saga of the first Buddhist school by Prof. W. M. Karunadasa

- ↑ Nightingale of Sri Lanka, by T.K.Premadasa (Asian Tribune)

- ↑ Fonseka, the political arriviste–a historical irony

- RAGHAVAN, M. D., The Karava of Ceylon: Society and Culture, K. V. G. de Silva, 1961.

- Caste Conflict and Elite Formation, The Rise of the Karava Elite in Sri Lanka 1500–1931. Michael Roberts 1982, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 81-7013-139-1

- Social Change in Nineteenth Century Ceylon. Patrick Peebles. 1995, Navrang ISBN 81-7013-141-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karava. |

- Karava web site - Kshatriya Maha Sabha Sri Lanka

- Karava - the blue-blooded Kshatriyas

- The Maha Oruwa (The Last in the tradition of the Indigenous Sailing Ships): plate 5

- The Bala (Power) Oruwa: world's fastest traditional sailing canoe