Kenneth Arthur Noel Anderson

| Sir Kenneth Arthur Noel Anderson | |

|---|---|

|

Anderson, pictured here in an Auster aircraft, 2 May 1943 | |

| Born |

25 December 1891 Madras, India |

| Died |

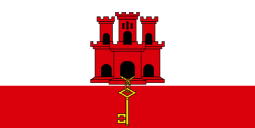

29 April 1959 (aged 67) Gibraltar |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/branch | British Army |

| Years of service | 1911–1952 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Seaforth Highlanders |

| Commands held |

East Africa Command (1945–46) Eastern Command (1942, 1944) Second Army (1943–44) First Army (1942–43) II Corps (1941–42) VIII Corps (1941) 1st Infantry Division (1940–41) 11th Infantry Brigade (1938–40) 152nd (Seaforth and Cameron Highlanders) Infantry Brigade 2nd Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath Military Cross Mentioned in Despatches (2) Knight of the Order of St John Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit (United States) Commander of the Legion of Honour (France) Croix de guerre (France) Grand Cross of the Order of Ouissam Alaouite (Morocco) Grand Cordon of the Order of Glory (Tunisia) Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of Ethiopia |

General Sir Kenneth Arthur Noel Anderson, KCB, MC (25 December 1891 – 29 April 1959) was a senior British Army officer who saw service in both World wars. He is mainly remembered as the commander of the British First Army during Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa. He had an outwardly reserved character and did not court popularity either with his superiors or with the public. General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote that he was "blunt, at times to the point of rudeness". In consequence he is less well known than many of his contemporaries. He handled a difficult campaign more competently than his critics suggest, but competence without flair was not good enough for a top commander in 1944.[1]

Early life and First World War

Anderson was born in British India, the son of a Scottish railway engineer, and was educated at Charterhouse School and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst before being commissioned in the Seaforth Highlanders in September 1911 as a second lieutenant.[2] His First World War service was in France, where he served with distinction. He was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for bravery in action and was wounded at the Battle of the Somme on the opening day, 1 July 1916. The citation for his MC read:

For conspicuous gallantry. Captain Anderson was severely wounded in front of an enemy first line trench. He endeavoured to struggle on, but progress was impossible as one of his legs was broken. Nevertheless, although exposed to heavy fire, he continued to direct and encourage his men.[3]

He took eighteen months to recover from the wounds he received, before rejoining his regiment in Palestine in time to celebrate victory. He was appointed an acting major in May 1918,[4] and reverted to captain in July 1919.[5]

In 1918 Anderson married Kathleen Gamble. She was the only daughter of Sir Reginald Arthur Gamble and his wife Jennie. Her brother was Ralph Dominic Gamble, a officer in the Coldstream Guards.

Inter-war career

Anderson's inter-war career was active. He served as adjutant to the Scottish Horse from 1920–24,[6][7] and was promoted to major during this posting.[8] He attended the Command and Staff College course at Quetta, where he apparently did not do that well. His superior, Colonel Percy Hobart, thought it "questionable whether he had the capacity to develop much." Other staff council also had reservations, but "hoped that he might suffice."[9] Anderson graduated from the Staff College, Camberley, in 1928 following which he took a staff posting (GSO2) in the 50th (Northumbrian) Division.[10] In 1930 Anderson was promoted lieutenant colonel[11] and at the age of 38 he commanded the 2nd Battalion of the Seaforths in the North West Frontier, for which he was mentioned in despatches and, as a full colonel,[12] went on to command the 152nd (Seaforth and Cameron) Infantry Brigade in August 1934.[13] Still as a full colonel in March 1936 he was appointed to a staff job (GSO1)[14] in India and in January 1938 was appointed acting brigadier to command 11th Brigade[15] which he trained hard, despite inadequate equipment.

Second World War

It was as commander of the 11th Brigade that Anderson saw service with the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). When Major General Bernard Montgomery was promoted to command II Corps during the evacuation from France, the departing II Corps commander, Lieutenant General Alan Brooke chose Anderson to take command of Montgomery's 3rd Infantry Division.[16] On returning to the United Kingdom after the withdrawal from Dunkirk Anderson was promoted to major general, and made a Companion of the Order of the Bath.[17] He was given command of the 1st Infantry Division[16] which was tasked with defending the coast of Lincolnshire before being promoted to lieutenant general in 1941[18] and given VIII Corps, then II Corps to command before becoming General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) Eastern Command in 1942.[16]

In spite of his lack of experience in commanding larger formations in battle, Anderson was given command of the British First Army, replacing Lieutenant General Edmond Schreiber who had developed a kidney disease and was not considered fit enough for active service in the Army's planned involvement in Operation Torch. The first choice replacement, General Sir Harold Alexander, had been almost immediately selected to replace General Claude Auchinleck as Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) Middle East in Cairo and his replacement, Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery, was himself redirected to the Western Desert to command the Eighth Army, following the death of Major General William Gott. Anderson therefore became the fourth commander in no more than a week.[16]

Following the Torch landings, although much of his troops and equipment had yet to arrive in the theatre, Anderson was keen to make an early advance from Algeria into Tunisia to preempt Axis occupation following the collapse of the Vichy French administration there. His available force, at this stage barely a division strong, was engaged in late 1942 in a race to capture Tunis before the Axis were able to build up their forces and launch a counterattack. This was unsuccessful although elements of his force got to within 16 miles (26 km) of Tunis before being pushed back.[19]

As further Allied forces arrived at the front they suffered from a lack of co-ordination. Eventually in late January 1943 General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, persuaded the French to place their newly formed XIX Corps under Anderson's First Army and also gave him responsibility for the overall "employment of American troops", specifically U.S. II Corps, commanded by Major General Lloyd Fredendall. However, control still proved problematical with forces spread over 200 miles (320 km) of front and poor means of communication (Anderson reported that he motored over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) in four days in order to speak to his corps commanders).[20] Anderson and Fredendall also failed properly to coordinate and integrate forces under their command.[21] Subordinates would later recall their utter confusion at being handed conflicting orders, not knowing which general to obey – Anderson, or Fredendall.[21] While Anderson was privately aghast at Fredendall's shortcomings, he seemed frozen by the need to preserve a united Allied front, and never risked his career by strongly protesting (or threatening to resign) over what many of his own American subordinates viewed as an untenable command structure.

II Corps later suffered a serious loss at Kasserine Pass, where Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel launched a successful offensive against Allied forces, first shattering French forces defending the central portion of the front, then routing the American II Corps in the south. While the lion's share of the blame fell on Fredendall, Anderson's generalship abilities were also seriously questioned by both British and Allied commanders.[16][22][23] When Fredendall disclaimed all responsibility for the poorly-equipped French XIX Corps covering the vulnerable central section of the Tunisian front, denying their request for support, Anderson allowed the request to go unfulfilled.[22][24] Anderson was also criticised for refusing Fredendall's request to retire to a defensible line after the initial assault in order to regroup his forces, allowing German panzer forces to overrun many of the American positions in the south.[22] Furthermore, the commander of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, Major General Ernest Nason Harmon, vehemently objected to the dispersal of his division's three combat commands on individual assignments requested by Anderson which he believed diluted the division's effectiveness and resulted in its heavy losses.[22][25]

In particular, the American generals Harmon and George S. Patton thought little of Anderson's ability to control large forces in battle.[25][26] Major-General Harmon had been in Thala on the Algerian border, witnessing the stubborn resistance of the British Nickforce, which held the vital road leading into the Kasserine Pass against the heavy pressure of the German 10th Panzer Division, which was under Rommel's direct command.[25] Commanding the British Nickforce was Brigadier Cameron Nicholson, an effective combat leader who kept his remaining forces steady under relentless German hammering. When the U.S. 9th Infantry Division's attached artillery arrived in Thala after a four-day, 800 miles (1,300 km) journey, it seemed like a godsend to Harmon. Inexplicably, the 9th Division was ordered by Anderson to abandon Thala to the enemy and head for the village of Le Kef, 50 miles (80 km) away, to defend against an expected German attack. Nicholson pleaded with the American artillery commander, Brigadier General Stafford LeRoy Irwin, to ignore Anderson's order and stay.[25] Harmon agreed with Nicholson and commanded, "Irwin, you stay right here!".[25] The 9th's artillery did stay, and with its 48 guns raining a whole year's worth of a (peacetime) allotment of shells, stopped the advancing Germans in their tracks. Unable to retreat under the withering fire, the Afrika Corps finally withdrew after dark.[25] With the defeat at Thala, Rommel decided to end his offensive.

As Allied and Axis forces built up in Tunisia, 18th Army Group HQ was formed in February 1943 under General Sir Harold Alexander to control all Allied forces in Tunisia. Alexander wanted to replace Anderson with Lieutenant General Oliver Leese, commander of XXX Corps of the Eighth Army, and Montgomery felt that Leese was ready for such a promotion, writing on the 17th of March, 1943 to Alexander "your wire re Oliver Leese. He has been through a very thorough training here and has learned his stuff well. I think he is quite fit to take command of First Army." Alexander later changed his mind, writing to Montgomery on the 29th of March that "I have considered the whole situation very carefully – I don't want to upset things at this stage."[27] Anderson managed to hold on to his position and performed well after V Corps held off the last Axis attack during Operation Ochsenkopf. In May 1943 he secured his position further when Allied forces won victory and the unconditional surrender of the Axis forces, 125,000 of whom were German. His rank of lieutenant-general was made substantive in July 1943[28] and he was advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in August.[29] General Eisenhower, his superior officer, had stated after observing Anderson in action that he "studied the written word until he practically burns through the paper" but later wrote of him that he was

...a gallant Scot, devoted to duty and absolutely selfless. Honest and straightforward, he was blunt, at times to the point of rudeness, and this trait, curiously enough, seemed to bring him into conflict with his British confreres more than it did with Americans. His real difficulty was shyness. He was not a popular type, but I had a real respect for his fighting heart. Even his most severe critic must find it difficult to discount the smashing victory he finally attained in Tunisia.[16][23][30]

Anderson was the first recipient of the American Legion of Merit in the grade of Chief Commander,[31] for his service as First Army commander in North Africa; he received his award on 18 June 1943.[32] On his return to Britain from Tunis he was initially given command of the Second Army during the preparations for the Normandy landings but the criticisms of Alexander and Montgomery (who in March 1943 had written to Alexander saying "...it is obvious that Anderson is completely unfit to command any army" and later described him as "a good plain cook")[1] had gained currency and in January 1944 he was replaced by Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey. Anderson was given Eastern Command, widely viewed as a demotion.[33] His career as a field commander was over and his last purely military appointment was as GOC-in-C East Africa Command.

Post-war

After the war he was military commander-in-chief and Governor of Gibraltar, where his most notable achievements were to build new houses to relieve the poor housing conditions, and the constitutional changes which established a Legislative Council. He was promoted full general in July 1949 when he was made a Knight of the Venerable Order of Saint John and retired in June 1952 and lived mainly in the south of France. His last years were filled with tragedy: his only son died in action in Malaya and his daughter also died after a long illness. Anderson died of pneumonia in Gibraltar in 1959.[34][35][36]

Notes

- 1 2 Mead (2007), p. 51

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 28532. p. 6882. 19 September 1911. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 29760. p. 9270. 1916-09-22. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31044. p. 14294. 29 November 1918. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 31471. p. 9412. 22 July 1919. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 31866. p. 4445. 13 April 1920. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 32912. p. 1724. 26 February 1924. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 32851. p. 5429. 7 August 1923. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Lippman, David H., World War II Plus 55", Article

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33462. p. 773. 1 February 1929. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33612. p. 726. 4 February 1930. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 34055. p. 3484. 1 June 1934. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 34081. p. 5400. 24 August 1934. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 34291. p. 3594. 5 June 1936. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 34477. p. 585. 28 January 1938. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mead (2007), p. 49

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 34893. p. 4244. 9 July 1940. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35170. p. 2937. 1941-05-20. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Mead (2007), p. 50.

- ↑ Anderson (1946), p. 8 The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. p. 5456. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- 1 2 Atkinson (2003), p. 324

- 1 2 3 4 Calhoun (2003), pp. 73–75

- 1 2 Atkinson (2003), p. 173

- ↑ Blumenson (1966), p. 177

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Murray, Brian J. Facing The Fox, America in World War II, (April 2006)

- ↑ Blumenson & Patton (1972), : Patton thought Anderson was "earnest, but dumb" a sentiment not dissimilar to that expressed by Anderson's superior, Major General Percy Hobart, when Anderson attended Quetta Staff college in the 1920s.

- ↑ Master of the Battlefield; Hamilton, Nigel; McGraw-Hill, 1983; pp 215–6

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36098. p. 3267. 16 July 1943. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36120. p. 3521. 3 August 1943. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ Lippman, David H., World War II Plus 55", Article

- ↑ http://www.foxfall.com/fmd-common-lom.htm Foxfall medals: Legion of Merit

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36125. p. 3579. 1943-08-06. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ "King's Collections : Archive Catalogues : Military Archives". kcl.ac.uk.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 39564. p. 3109. 3 June 1952. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 39433. p. 137. 1 January 1952. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 38665. p. 3449. 15 July 1949. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

References

- Anderson, Lt.-General Kenneth (1946). Official despatch by Kenneth Anderson, GOC-in-C First Army covering events in NW Africa, 8 November 1942 – 13 May 1943 published in The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37779. pp. 5449–5464. 5 November 1946. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- Atkinson, Rick (2003). An Army at Dawn: The War in North Africa, 1942–1943. New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-7448-1.

- Blaxland, Gregory (1977). The Plain Cook and the Great Showman : The First and Eighth Armies in North Africa. Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0185-4.

- Blumenson, Martin (1966). Kasserine Pass. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 3947767.

- Blumenson, Martin; Patton, George S. (1972). The Patton Papers 1885–1940. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-12706-8.

- Calhoun, Mark T. (2003). Defeat at Kasserine: American Armor Doctrine, Training, and Battle Command in Northwest Africa, World War II. Ft. Leavenworth, KS: Army Command and General Staff College.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1997) [1948]. Crusade in Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5668-X.

- Hamilton, Nigel (1983). Master of the Battlefield: Monty's War Years 1942–1944. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-025806-6.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A Biographical Guide to the Key British Generals of World War II. Stroud (UK): Spellmount. p. 544 pages. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

- Smart, Nick (2005). Biographical Dictionary of British Generals of the Second World War. Barnsley, U.K.: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-049-6.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- The Times obituary (30 April 1959).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kenneth Arthur Noel Anderson. |

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Harold Alexander |

General Officer Commanding the 1st Infantry Division June 1940 – May 1941 |

Succeeded by Edwin Morris |

| Preceded by Harold Franklyn |

GOC, VIII Corps May 1941– November 1941 |

Succeeded by Arthur Grassett |

| Preceded by Edmund Osborne |

GOC, II Corps November 1941– April 1942 |

Succeeded by Sir James Steele |

| Preceded by Laurence Carr |

GOC-in-C Eastern Command April 1942 – August 1942 |

Succeeded by Sir James Gammell |

| Preceded by Edmond Schreiber |

GOC-in-C First Army August 1942 – July 1943 |

Succeeded by Post disbanded |

| Preceded by New post |

GOC-in-C Second Army July 1943 – January 1944 |

Succeeded by Miles Dempsey |

| Preceded by Sir James Gammell |

GOC-in-C Eastern Command January 1944 – December 1944 |

Succeeded by Sir Alan Cunningham |

| Preceded by Sir William Platt |

GOC East Africa Command 1945–1946 |

Succeeded by William Dimoline |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Ralph Eastwood |

Governor of Gibraltar 1947–1952 |

Succeeded by Sir Gordon MacMillan |