Noble train of artillery

|

An ox team hauling Ticonderoga's guns | |

| Date | November 17, 1775 – January 25, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Location | British provinces of New York and Massachusetts Bay |

| Participants | Henry Knox |

| Outcome | Fortification of Dorchester Heights |

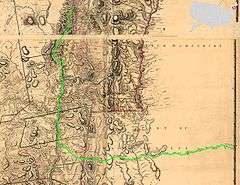

The noble train of artillery, also known as the Knox Expedition, was an expedition led by Continental Army Colonel Henry Knox to transport heavy weaponry that had been captured at Fort Ticonderoga to the Continental Army camps outside Boston, Massachusetts during the winter of 1775–1776.

Knox went to Ticonderoga in November 1775, and, over the course of three winter months, moved 60 tons[1] of cannons and other armaments by boat, horse and ox-drawn sledges, and manpower, along poor-quality roads, across two semi-frozen rivers, and through the forests and swamps of the lightly inhabited Berkshires to the Boston area.[2][3] Historian Victor Brooks has called Knox's exploit "one of the most stupendous feats of logistics" of the entire American Revolutionary War.[4]

The route by which Knox moved the weaponry is now known as the Henry Knox Trail, and the states of New York and Massachusetts have erected markers along the route.

Background

Shortly after the American Revolutionary War broke out with the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, Benedict Arnold, a militia leader from Connecticut who had arrived with his unit in support of the Siege of Boston, proposed to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that Fort Ticonderoga, on Lake Champlain in the Province of New York, be captured from its small British garrison. One reason he gave to justify the move was the presence at Ticonderoga of heavy weaponry. On May 3, the committee gave Arnold a Massachusetts colonel's commission and authorized the operation.[5]

The idea to capture Ticonderoga had also been raised to Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys in the disputed New Hampshire Grants territory (present-day Vermont).[6] Allen and Arnold joined forces, and on May 10 a force of 83 men captured the fort without a fight. The next day, a detachment of men captured the nearby Fort Crown Point, again without combat.[7]

Arnold began to inventory the two forts for usable military equipment.[8] Hampered by a lack of resources and conflict over command of the forts, first with Allen, and later with a Connecticut militia company sent to hold the fort in June, Arnold eventually abandoned the idea of transporting the armaments to Boston and resigned his commission.[9]

Expedition planning

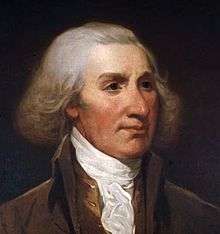

In July 1775, George Washington assumed command of the forces outside Boston.[10] One of the significant problems he identified in the nascent Continental Army there was a lack of heavy weaponry, which made offensive operations virtually impossible. While it is uncertain exactly who proposed the operation to retrieve the Ticonderoga cannons (biographers tend to credit either Knox or Arnold with giving Washington the idea), Washington eventually chose the young Henry Knox for the job.[11]

Knox, a 25-year-old bookseller with an interest in military matters, served in the Massachusetts militia, and become good friends with Washington on his arrival at Boston. When Washington gave Knox the assignment, he wrote that "no trouble or expense must be spared to obtain them."[12] On November 16 Washington, issued orders to Knox to retrieve the cannons (and authorized £1000 for the purpose), and wrote to General Philip Schuyler asking him to assist Knox in the endeavor.[13] Washington's call for the weapons was echoed by the Second Continental Congress, which issued Knox a colonel's commission in November, which did not reach him until he returned from the expedition.[14]

Knox departed Washington's camp on November 17, and after traveling to New York City for supplies, reached Ticonderoga on December 5. The night before, at Fort George at the southern end of Lake George, he shared a cabin with a young British prisoner named John André. André had been taken prisoner during the Siege of Fort St. Jean and was on his way south to a prison camp. The two were of a similar age and temperament, and found much common ground to talk about.[15] It was not to be their last meeting; the next time they met, Knox presided over the court martial that convicted and sentenced André to death for his role in Benedict Arnold's treason.[16]

Sources

The primary sources for much of the daily activity in this journey are Knox's diary and letters. While his description of some of the events and dates is detailed, there are significant gaps, and significant portions of the journey, especially much of the Massachusetts section, are poorly documented. Some of these gaps occur because Knox did not write about them, and others because pages are missing from the diary.[17] While there are other sources that confirm some of Knox's details or report additional details, parts of the route are not known with certainty, and modern descriptions (including the placement of markers for the Henry Knox Trail) of those parts are based on what is known about roads across Massachusetts at the time.[18] Nevertheless, the route was more or less in the corridor of today's Massachusetts Turnpike (Interstate 90).

Albany

Upon arrival at Ticonderoga, Knox immediately set about identifying the equipment to take and organizing its transport.[19] He selected 59 pieces of equipment, including cannons ranging in size from four to twenty-four pounders, mortars, and howitzers. He estimated the total weight to be transported at 119,000 pounds (about 60 tons or 54 metric tons). The largest pieces, the twenty-four pounder "Big Berthas", were 11 feet (3.4 m) long and estimated to weigh over 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg).[12]

The equipment was first carried overland from Ticonderoga to the northern end of Lake George, where most of the train was loaded onto a scow-like ship called a gundalow.[12] On December 6, the gundalow set sail for the southern end of the lake, with Knox sailing ahead in a small boat. Ice was already beginning to cover the lake, but the gundalow, after grounding once on a submerged rock, reached Sabbath Day Point. The next day, they sailed on, again with Knox going ahead. While he reached Fort George in good time, the gundalow did not appear when expected. A boat sent to check on its progress reported that the gundalow had foundered and sunk not far from Sabbath Day Point. While this at first appeared to be a serious setback, Knox's brother William, captain of the gundalow, reported that she had foundered, but that her gunnels were above the water line, and that she could be bailed out. This was done, the ship was refloated, and two days later, the gundalow arrived at the southern end of the lake.[20]

On December 17, Knox wrote to Washington that he had built "42 exceeding strong sleds, and have provided 80 yoke of oxen to drag them as far as Springfield",[21] and that he hoped "in 16 or 17 days to be able to present your Excellency a noble train of artillery".[19]

Knox then set out for Albany ahead of the train. At Glens Falls, he crossed the frozen Hudson River and proceeded on through Saratoga, reaching New City (present-day Lansingburg), just north of Albany, on Christmas Day. Two feet (0.6 m) of snow fell that day, slowing his progress, as the snow-covered route needed to be broken open. The next day, again slowed by significant snow on the ground, he finally reached Albany. There, he met with General Philip Schuyler, and the two of them worked over the next few days to locate and send north equipment and personnel to assist in moving the train south from Lake George. While the snowfall was sufficient for the use of sleds to move the train overland, the river ice was still too thin to move it over the Hudson. Knox and his men tried to accelerate the process of thickening the river ice by pouring additional water on top of existing ice. By January 4, the first of the cannon had arrived at Albany. On the way to Albany, and again on crossing the Hudson heading east from there toward Massachusetts, cannons crashed through the ice into the river. In every instance, the cannon was recovered. On January 9, the last of cannons had crossed the Hudson, and Knox rode ahead to oversee the next stage of the journey.[22]

Crossing the Berkshires

Details of the remaining journey are sketchy, as Knox's journal ends on January 12. He reached the vicinity of Claverack, New York, on January 9, and proceeded through the Berkshires, reaching Blandford, Massachusetts, two days later.[23] There, the lead crew refused to continue owing to a lack of snow and the upcoming steep descent to the Connecticut River valley. Knox hired additional oxen and persuaded the crew to go on. As the train moved further east, news of it spread, and people came out to watch it pass. In Westfield, Knox loaded one of the big guns with powder and fired it, to the applause of the assembled crowd.[24]

At Springfield, Knox had to hire new work crews, as his New York-based crews wanted to return home.[25] John Adams reported seeing the artillery train pass through Framingham on January 25. Two days later, Knox arrived in Cambridge and personally reported to Washington that the artillery train had arrived. According to Knox's accounting, he spent £521 on an operation he had hoped would take two weeks, that instead took ten weeks.[26]

Arrival

When the equipment began to arrive in the Boston area, Washington, seeking to end the siege, formulated a plan to draw at least some of the British out of Boston, at which point he would launch an attack on the city across the Charles River. Pursuing this plan, he placed cannons from Ticonderoga at Lechmere's Point and Cobble Hill in Cambridge, and on Lamb's Dam in Roxbury.[27] These batteries opened fire on Boston on the night of March 2, while preparations were made to fortify the Dorchester Heights, from which cannons could threaten both the city and the British fleet in the harbor. On the night of March 4, Continental Army troops occupied this high ground.[28][29]

British General William Howe first planned to contest this move by assaulting the position, but a snowstorm prevented its execution. After further consideration, he decided instead to withdraw from the city. On March 17, British troops and Loyalist colonists boarded ships and sailed for Halifax, Nova Scotia.[30]

Henry Knox went on to become the chief artillery officer of the Continental Army, and later served as the first United States Secretary of War.[31]

Legacy

To commemorate Knox's achievement, at the time of its sesquicentennial (150th anniversary), the states of New York and Massachusetts both placed historical markers along the route he was believed to have taken at the time. In 1972, markers in New York were moved when new information surfaced about the train's movements between Albany and the state boundary. Most of the markers in Massachusetts are along a route the train was assumed to take, given the sparsity of documentation and what was known about roads in Massachusetts at the time.[32]

Fort Knox, an Army post in Kentucky most famous for being the site of the United States Bullion Depository, was named after Henry Knox.

Notes

- ↑ Ware (2000), p. 18

- ↑ Ware (2000), pp. 19–24

- ↑ N. Brooks (1900), p. 38

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 210

- ↑ Martin (1997), pp. 63–65

- ↑ Martin (1997), p. 67

- ↑ Martin (1997), pp. 70–73

- ↑ Martin (1997), p. 76

- ↑ Martin (1997), pp. 80–95

- ↑ N. Brooks (1900), p. 32

- ↑ See for example: N. Brooks, p. 38, and Martin, p. 106. This trend is visible in other biographies of Knox and Arnold, although Knox is more likely to be explicitly credited.

- 1 2 3 Ware (200), p. 19

- ↑ N. Brooks (1900), pp. 38–39

- ↑ N. Brooks (1900), p. 34

- ↑ Callahan (1958), p. 39

- ↑ Callahan (1958), p. 40

- ↑ See the diary contents at Knox (1876), pp. 322–326

- ↑ See e.g. the inventory record for marker 21 on the trail.

- 1 2 N. Brooks (1900), p. 40

- ↑ Ware (2000), p. 20

- ↑ Ware (2000), pp. 21–22

- ↑ Knox (1867), pp. 323–324. Callahan (1958), pp. 46–50

- ↑ Knox (1867), p. 325

- ↑ Ware (2000), p. 24

- ↑ Callahan (1958), p. 54

- ↑ Drake (1873), p. 23

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 224

- ↑ French (1911), p. 406

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 225

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), pp. 228–230

- ↑ Drake (1873), pp. 21, 127

- ↑ Knox Trail official New York site

References

- Brooks, Noah (1900). Henry Knox, a Soldier of the Revolution: Major-general in the Continental Army, Washington's Chief of Artillery, First Secretary of War Under the Constitution, Founder of the Society of the Cincinnati; 1750–1806. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 77547631.

- Brooks, Victor (1999). The Boston Campaign. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing. ISBN 1-58097-007-9. OCLC 42581510.

- Callahan, North (1958). Henry Knox: General Washington's General. New York: Rinehart.

- Drake, Francis Samuel (1873). Life and correspondence of Henry Knox. S. G. Drake. OCLC 2358685.

- French, Allen (1911). The Siege of Boston. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 3927532.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero (An American Warrior Reconsidered). New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5560-7. (This book is primarily about Arnold's service on the American side in the Revolution, giving overviews of the periods before the war and after he changes sides.)

- Knox, Henry (1876). Waters, Henry Fitz-Gilbert, ed. Henry Knox's Diary. New England Historical and Genealogical Register.

- Ware, Susan (2000). Forgotten Heroes: Inspiring American Portraits from Our Leading Historians. Portland, OR: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86872-1. OCLC 45179918.

- "Knox Trail official New York site". New York State Museum. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- "Knox Trail marker 21". New York state Museum. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

External links