LGBT history in the United States

This article concerns the history of LGBT people in the United States.

17th - 19th century

With the establishment of the first European settlements in what is now the United States, the influence of Christianity, Christian mores and legal restrictions regarding sexual orientation and gender identity gradually took hold. Initially, such crimes as "sodomy" and "buggery" were considered capital offenses, while cross-dressing was considered a felony punishable by imprisonment or other forms of corporal punishment.

Following the American Revolution and independence, the status of same-sex sexual relations as capital-worthy felonies was gradually reduced by the states from felonies worthy of life sentences to imprisonment at maximum. However, LGBT persons were present throughout the post-independence history of the country, with gay men having served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Restrictions against loitering and solicitation of sex in public places were installed in the late 19th century by many states (namely to target, among other things, solicitation for same-sex sexual favors), and increasingly tighter restrictions upon "perverts" were common by the turn of the century.

Several examples of same-sex couples living in relationships that functioned as marriages, even if they could not be legally sanctified as such, have been located by historians.[1] Rachel Hope Cleves documents the relationship of 19th-century Vermont residents Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake in her 2014 book Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America,[1] and Susan Lee Johnson included the story of Jason Chamberlain and John Chaffee, a California couple who were together for over 50 years until Chaffee's death in 1903, in her 2000 book Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush.[2]

Historians have also identified numerous records of people on the transgender spectrum in the 19th century. In his book Re-Dressing America's Frontier Past, historian Peter Boag wrote about figures such as writers Alan L. Hart and Jack Bee Garland, carpenter Ferdinand Haisch, Charles Harrington and Jeanne Bonnet.[2]

1900-1965

In the United States, as early as the turn of the 20th century several groups worked in hiding to avoid persecution and to advance the rights of homosexuals, but little is known about them.[3] A better documented group is Henry Gerber's Society for Human Rights (formed in Chicago in 1924), which was quickly suppressed within months of its establishment.[4] Serving as an enlisted man in occupied Germany after World War I, Gerber had learned of Magnus Hirschfeld's pioneering work. Upon returning to the U.S. and settling in Chicago, Gerber organized the first documented public homosexual organization in America and published two issues of the first gay publication, entitled Friendship and Freedom. Meanwhile, during the 1920s, LGBT persons found employment as entertainers or entertainment assistants for various urban venues in cities such as New York City.

In 1948, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male was published by Alfred Kinsey, a work which was one of the first to look scientifically at the subject of sexuality. Kinsey's claim, that approximately 10% of the adult male population (and about half that number among females) were predominantly or exclusively homosexual for at least three years of their lives, was a dramatic departure from the prevailing beliefs of the time. Before its publication, homosexuality was not a topic of discussion, generally, but afterwards it began to appear even in mainstream publications such as Time magazine, Life magazine, and others.

During the late 1940s – 1960s, a handful of radio and television news programs aired episodes that focused on homosexuality, with some television movies and network series episodes featuring gay characters or themes. Several organizations, including the Mattachine Society, the Daughters of Bilitis and the Society for Individual Rights, campaigned for the rights of "homophiles".

In 1958, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the gay publication ONE, Inc., was not obscene and thus protected by the First Amendment. The California Supreme Court extended similar protection to Kenneth Anger's homoerotic film, Fireworks and Illinois became the first state to decriminalize sodomy between consenting adults in private.

Little change in the laws or mores of society was seen until the mid-1960s, the time the sexual revolution began. This was a time of major social upheaval in many social areas, including views of gender roles and human sexuality.

1965-1999

Gay Liberation

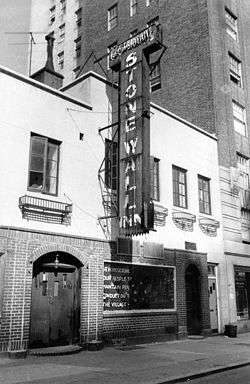

In the late 1960s, the more socialistic "liberation" philosophy that had started to create different factions within the civil rights, Black Power, anti-war, and feminist movements, also engulfed the homophile movement. A new generation of young gay and lesbian Americans saw their struggle within a broader movement to dismantle racism, sexism, western imperialism, and traditional mores regarding drugs and sexuality. This new perspective on Gay Liberation had a major turning point with the Stonewall riots in 1969.

On June 27, 1969 the police raided a gay/transgender bar, which was a common practice at the time. This type of raid, which was often conducted during city elections, had a new development as some of the patrons in the bar began actively resisting the police arrests. Some of what followed is in dispute, but what is not in dispute is that for the first time a large group of LGBT Americans who had previously had little or no involvement with the organized gay rights movement rioted for three days against police harassment and brutality. These new activists were not polite or respectful but rather angry activists who confronted the police and distributed flyers attacking the Mafia control of the gay bars and the various anti-vice laws that allowed the police to harass gay men and gay drinking establishments. This second wave of the gay rights movement is often referred to as the Gay Liberation movement to draw a distinction with the previous homophile movement.

New gay liberation organizations were created such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in New York City and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). In keeping with the mass frustration of LGBT people, and the adoption of the socialistic philosophies that were being propagated in the late 1960s–1970s, these new organizations engaged in colorful and outrageous street theater (Gallagher & Bull 1996). The GLF published "A Gay Manifesto" that was influenced by Paul Goodman's work titled "The Politics of Being Queer" (1969).

The gay liberation movement spread to countries throughout the world and heavily influenced many of the modern gay rights organizations. Out of this vein, a number of modern-day advocacy organizations were established with differing approaches: the Human Rights Campaign, formed in 1980, follows a more middle class-oriented and reformist tradition, while other organizations such as the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), formed in 1973, tries to be grassroots-oriented and support local and state groups to create change from the ground up.

The group Dyketactics was the first LGBTIQ group in the U.S. to take the police to court for police brutality in the case Dyketactics vs. The City of Philadelphia. Members of Dyketactics who took the police to court, now known as "The Dyketactics Six," were beaten by the Philadlephia Civil Defence Squad in a demonstration for lgbt rights on December 4, 1975.[5]

Gay migration

In the 1970s many gay people moved to cities such as San Francisco.[6] Harvey Milk, a gay man, was elected to the city's Board of Supervisors, a legislative chamber often known as a city council in other municipalities.[7] Milk was assassinated in 1978 along with the city's mayor, George Moscone.[8] The White Night Riot on May 21, 1979 was a reaction to the manslaughter conviction and sentence given to the assassin, Dan White, which were thought to be too lenient. Milk played an important role in the gay migration and in the gay rights movement in general.[9][10]

The first national gay rights march in the United States took place on October 14, 1979 in Washington, D.C., involving perhaps as many as 100,000 people.[11][12]

Historian William A. Percy considers that a third epoch of the gay rights movement began in the early 1980s, when AIDS received the highest priority and decimated its leaders, and lasted until 1998, when advanced antiretroviral therapy greatly extended the life expectancy of those with AIDS in developed countries.[13] It was during this era that direct action groups such as ACT UP were formed.[14]

Decriminalization of relations

In 1962, consensual sexual relations between same-sex couples was decriminalized in Illinois, the first time that a state legislature took such an action. Over the next several decades, such relations were gradually decriminalized on a state-by-state basis.

Reaction of opposition

From the beginning of the modern LGBT rights movement in the United States, social-conservative opposition to the legal legitimization or recognition of LGBT people. Efforts to recriminalize same-sex sexual relations and strip LGBT-inclusive human rights ordinances and laws from the books in various jurisdictions became rallying points of social conservative opposition, as was opposition against other "liberal" reforms such as abortion rights. This began to form a core of policy for Republican politicians after 1994.

The long-standing prohibition on open homosexuals serving in the United States military was reinforced under "Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT), a 1996 Congressional policy which allowed for homosexual people to serve in the military provided that they did not disclose their sexual orientation. The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) of 1996 also barred the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples in any legal manner.

21st century

2000-2008

The 21st century became an increasingly important time for LGBT rights and civics advocates in the United States, as the Republican Party under George W. Bush pandered to the social conservative activist base in order to enact amendments outlawing same-sex marriage and other unions through state-level referendum, the height of the movement being in 2004. At the same time, however, Massachusetts, in 2004 and under a Republican governor, became the first state to legalize and issue marriage licenses for same-sex couples. A year earlier, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Lawrence v. Texas that consensual sexual activity between adults was protected under the Fourteenth Amendment and therefore all anti-sodomy laws in the United States were rendered unconstitutional.

2008-present

The tipping point of activism in favor of same-sex marriage came in 2008, when the California State Supreme Court ruled that the previous proposition which barred the legalization of same-sex marriage in California was unconstitutional under the United States Constitution. Over 18,000 couples then obtained legal licenses from May until November of the same year, when another statewide proposition reinstated the ban on same-sex marriage. This was received by nationwide protests against the ban and a number of legal battles which were projected to end up in the Supreme Court of the United States.

The election of Barack Obama as the first African-American president of the United States (on the same day as the California ban on same-sex marriage was enacted) signified the beginning of a more nuanced federal policy to LGBT citizens. Obama advocated for the repeal of DADT, which was passed in December 2010, and also withdrew legal defense of DOMA in 2011, despite Republican opposition. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2010 was also the first major hate crimes legislation in federal legislation history to recognize gender identity as a protected class.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, attention was also paid to the rise of suicides and the lack of self-esteem by LGBT children and teenagers due to homophobic bullying. The "It Gets Better Project", founded and promoted by Dan Savage, was launched in order to counter the phenomenon, and various initiatives were taken by both activists and politicians to impose better conditions for LGBT students in public schools. Also, in 2013 there were some major victories for the LGBT community by returning same-sex marriage to California in Hollingsworth v. Perry and the full federal recognition of fully legal same-sex marriages in United States v. Windsor. In 2015, the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage nationwide in a landmark decision, Obergefell v. Hodges.

On June 12, 2016, 49 people, mostly of Latino descent, where shot and killed by Omar Mateen during Latin Night at the Pulse gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The shooting was the deadliest mass shooting and worst act of violence against the LGBT community in American history.

See also

- Bisexuality in the United States

- History of gay men in the United States

- History of lesbianism in the United States

- History of transgender people in the United States

- LGBT demographics of the United States

- LGBT historic places in the United States

- Biphobia

- Homophobia

- Lesbophobia

References

- 1 2 "The improbable, 200-year-old story of one of America's first same-sex ‘marriages’". Washington Post, March 20, 2015.

- 1 2 "Gold Rush Gays". The Bay Area Reporter, November 20, 2014.

- ↑ Norton, Rictor (12 February 2005). "The Suppression of Lesbian and Gay History".

- ↑ Bullough, Vern (17 April 2005). "Because the Past is the Present, and the Future too.". History News Network.

- ↑ Paola Bacchetta. "Dyketactics! Notes Towards an Un-silencing." In Smash the Church, Smash the State: The Early Years of Gay Liberation, edited by Tommi Avicolli Mecca, 218-231. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2009.

- ↑ http://gsaday.org/featured/lgbt-straight-allied-history/

- ↑ Cone, Russ (January 8, 1978). "Feinstein Board President", The San Francisco Examiner, p. 1.

- ↑ Turner, Wallace (November 28, 1978). "Suspect Sought Job", The New York Times, p. 1.

- ↑ Cloud, John (June 14, 1999). "Harvey Milk", Time. Retrieved on August 4, 2013.

- ↑ 40 Heroes, The Advocate (September 25, 2007), Issue 993. Retrieved on August 4, 2013.

- ↑ Ghaziani, Amin. 2008. "The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington". The University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Thomas, Jo (October 15, 1979), "Estimated 75,000 persons parade through Washington, DC, in homosexual rights march. Urge passage of legislation to protect rights of homosexuals", New York Times Abstracts, p. 14

- ↑ Percy & Glover 2005

- ↑ Crimp, Douglas. AIDS Demographics. Bay Press, 1990. (Comprehensive early history of ACT UP, discussion of the various signs and symbols used by ACT UP).