Lalon

| Lalon Fokir Saint /Sai, Shah সাঁই, শাহ (from Persian سای) | |

|---|---|

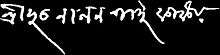

Lalon's only portrait sketched during his lifetime by Jyotirindranath Tagore in 1889. | |

| Native name | লালন |

| Born |

c. 1772 Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Died |

17 October 1890 Cheuriya, Kushtia, Bengal Presidency, British India (now in Bangladesh) |

| Resting place |

Cheuriya, Kushtia, Bangladesh 23°53′44″N 89°09′07″E / 23.89556°N 89.15194°E |

| Other names | Baul Shamrat |

| Title | Mahatma/Fakir |

| Spouse(s) | Bishōkha |

Lalon, also known as Lalon Sain, Lalon Shah, Lalon Fakir or Mahatma Lalon (c. 1772 – 17 October 1890; Bengali: 1 Kartik, 1179),[1] was a Bengali Baul saint, mystic, songwriter, social reformer and thinker. Considered an archetypal icon of Bengali culture, Lalon inspired and influenced many poets, social and religious thinkers including Rabindranath Tagore,[2][3][4] Kazi Nazrul Islam,[5] and Allen Ginsberg[6] albeit he "rejected all distinctions of caste and creed".[7] Widely celebrated as an epitome of religious tolerance, he was also accused of heresy during his lifetime and after his death. In his songs, Lalon envisioned a society where all religions and beliefs would stay in harmony. He founded the institute known as Lalon Akhrah in Cheuriya, about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from Kushtia railway station. His disciples dwell mostly in Bangladesh and West Bengal. Every year on the occasion of his death anniversary, thousands of his disciples and devotees assemble at Lalon Akhrah, and pay homage to the departed guru through celebration and discussion of his songs and philosophy for three days.[7] In 2004, Lalon was placed at number 12 in the BBC's poll of the Greatest Bengali of All Time.[8][9]

Biography

Everyone asks, "What religion does Lalon belong to in this world?"

Lalon answers, "What does religion look like?"

I've never laid eyes upon it.

Some use Malas (Hindu rosaries),

others Tasbis (Muslim rosaries), and so people say

they belong to different religion.

But do you bear the sign of your religion

when you come (to this world) or when you leave (this world)?

— Lalon[10]

[Edited to give a better translation]

There are few reliable sources for the details of Lalon's early life as he was reticent in revealing his past.[2] It is not known whether he was born in a Hindu or a Muslim family.[11] Lalon had no formal education.[12]

One account relates that Lalon, during a pilgrimage to the temple of Jagannath with others of his native village, he contracted smallpox and was abandoned by his companions on the banks of the Kaliganga River,[13] from where Malam Shah and his wife Matijan, members of the weaver community in a Muslim-populated village, Cheuriya, took him to their home to convalesce. They gave Lalon land to live where he founded a musical group and remained to compose and perform his songs, inspired by Shiraj Sain, a musician of that village. Lalon lost the sight of his one eye in smallpox.[11] Researchers note that Lalon was a close friend of Kangal Harinath, one of the contemporary social reformers and was a disciple of Lalon.[14]

Lalon lived within the zamindari of the Tagores in Kushtia and had visited the Tagore family.[15] It is said that zamindar Jyotirindranath Tagore sketched the only portrait of Lalon in 1889 in his houseboat on the river Padma.[16][17] Lalon died at Chheuriya on 17 October 1890 at the age of 116. The news of his death was first published in the newspaper Gram Barta Prokashika, run by Kangal Harinath.[18] Lalon was buried at the middle of his dwelling place known as his Akhra.[19]

Philosophy

How does the Unknown bird go,

into the cage and out again,

Could I but seize it,

I would put the fetters of my heart,

around its feet.

The cage has eight rooms and nine closed doors;

From time to time fire flares out;.

Above there is a main room,

The mirror-chamber

— Lalon's song translated by Brother James

Lalon was against religious conflict and many of his songs mock identity politics that divide communities and generate violence.[20] He even rejected nationalism at the apex of the anti-colonial nationalist movements in the Indian subcontinent.[21] He did not believe in classes or castes, the fragmented, hierarchical society, and took a stand against racism.[22] Lalon does not fit the "mystical" or "spiritual" type who denies all worldly affairs in search of the soul: he embodies the socially transformative role of sub-continental bhakti and sufism. He believed in the power of music to alter the intellectual and emotional state in order to be able to understand and appreciate life itself.

The texts of his songs engage in philosophical discourses of Bengal, continuing Tantric traditions of the Indian subcontinent, particularly Nepal, Bengal and the Gangetic plains. He appropriated various philosophical positions emanating from Hindu, Jainist, Buddhist and Islamic traditions, developing them into a coherent discourse without falling into eclecticism or syncretism. He explicitly identified himself with the Nadiya school, with Advaita Acharya, Nityananda and Chaitanya. He was greatly influenced by the social movement initiated by Chaitanya against differences of caste, creed and religion. His songs reject any absolute standard of right and wrong and show the triviality of any attempt to divide people whether materially or spiritually.

Works

Lalon composed numerous songs and poems, which describe his philosophy. It is estimated that Lalon composed about 2,000 - 10,000 songs, of which only about 800 songs are generally considered authentic.[23] Lalon left no written copies of his songs, which were transmitted orally and only later transcribed by his followers. Also, most of his followers could not read or write either, so few of his songs are found in written form.[24] Rabindranath Tagore published some of the Lalon song in the monthly Prabasi magazine of Kolkata.[25]

Among his most popular songs are

- Shob Loke Koy Lalon Ki Jat Shongshare,

- Khachar Bhitor Ochin Pakhi kyamne ashe jaay,

- Jat Gelo Jat Gelo Bole,

- Dekhna Mon Jhokmariay Duniyadari,

- Pare Loye Jao Amai,

- Milon Hobe Koto Dine,

- Ar Amare Marishne Ma,

- Tin Pagoler Holo Mela, etc.

The songs of Lalon aim at an indescribable reality beyond realism. He was observant of social conditions and his songs spoke of day-to-day problems in simple yet moving language. His philosophy was expressed orally, as well as through songs and musical compositions using folk instruments that could be made from materials available at home; the ektara (one-string musical instrument) and the duggi (drum).

Songs of Lalon were mainly confined to the baul sects. After the Independence of Bangladesh, they reached the urban people through established singers. Many of them started using instruments other than the ektara and baya. Some started using classical bases for a polished presentation to appeal to the senses of the urban masses.

According to Farida Parveen, a renowned Lalon singer, the pronunciation of the words were also refined in order to make their meanings clearer, whereas the bauls' pronunciations are likely to have local influence.[12]

Legacy and depictions in popular culture

In 1963, a mausoleum and research centre were built at the site of his shrine in Kushtia, Bangladesh. Thousands of people come to the shrine (known in Bengali as an Akhra) twice a year, at Dol Purnima in the month of Falgun (February to March) and in October, on the occasion of the anniversary of his death. During these three-day song melas, people, particularly Muslim fakirs and Bauls pay tribute. Among the modern singers of Baul music Farida Parveen and Anusheh Anadil are internationally known for singing Lalon songs.

Film and literature

Lalon has been portrayed in literature, film, television drama, and in the theatre. The first biopic of Lalon titled Lalon Fakir (1973) was directed by Syed Hasan Imam.[26] Prosenjit portrayed Lalan in the Moner Manush, a 2010 Bengali film based on the life and philosophy of Lalon.[27] The film was an adaptation of Sunil Gangopadhyay's biographical novel of the same name. This film directed by Goutam Ghose, won award for the "best feature film on national integration" at the 58th Indian National Film Awards.[28] It also won Best Film prize at the 41st International Film Festival of India held at Goa from 22 Nov to 02 Dec 2010.[29]

In 2004, Tanvir Mokammel directed the film Lalon in which Raisul Islam Asad portrayed Lalon.[30]

Allen Ginsberg wrote a poem in 1992 named "After Lalon", where he warned people against the dangers of fame and the attachments to the worldly things.[31]

Gallery

References

- ↑ Basantakumar Pal, Sri; Chowdhury, Abul Ahasan (Editor) (2012). Mahātmā Lālana Phakira (1. Bhāratīẏa saṃskaraṇa. ed.). Kalakātā: Gāṅacila. ISBN 9789381346280. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 Caudhurī, Ābadula Āhasāna (1992). Lālana Śāha, 1774 - 1890 (1. punarmudraṇa. ed.). Ḍhākā: Bāṃlā Ekāḍemī. ISBN 9840725971. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Urban, Hugh B. (2001). Songs of ecstasy tantric and devotional songs from colonial Bengal. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-19-513901-3. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Tagore, Rabindranath; K. Stewart, Tony (Translation); Twichell, Chase (Translation) (2003). The lover of God. Port Townsend, Wash.: Consortium Book Sales & Dist. p. 94. ISBN 1556591969.

- ↑ Hossain, Abu Ishahaq (2009). Lalon Shah, the great poet. Dhaka: Palal Prokashoni. p. 148. ISBN 9846030673. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Ginsberg, Allen; Foley, Jack (Winter–Spring 1998). "Same Multiple Identity: An Interview with Allen Ginsberg". Discourse. Wayne State University Press. 20 (1/2, The Silent Beat): 158–181. ISSN 1522-5321. JSTOR 41389881.

- 1 2 Ahmed, Wakil; Karim, Anwarul (2012). "Lalon Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ "Listeners name 'greatest Bengali'". BBC News. 14 April 2004. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ↑ "Bangabandhu judged greatest Bangali of all time". The Daily Star. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- ↑ Lopez, Donald (1995). Religions in India in Practice - "Baul Songs". Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 187–208. ISBN 0-691-04324-8.

- 1 2 Seabrook, Jeremy (2001). Freedom unfinished : fundamentalism and popular resistance in Bangladesh today. London: Zed Books. p. 52. ISBN 1856499081. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- 1 2 Tamanna Khan (29 October 2010). "Lalon Purity vs Popularity". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ↑ Capwell, Charles (May 1988). "The popular expression of religious syncretism: the Bauls of Bengal as Apostles of Brotherhood". Popular Music. Cambridge University Press. 7 (02): 123. doi:10.1017/S0261143000002701.

- ↑ Lorea, Carola Erika (2013). "'Playing the Football of Love on the Field of the Body': The Contemporary Repertoire of Baul Songs". Religion and the Arts. Brill. 17 (4): 416–451. doi:10.1163/15685292-12341286. ISSN 1568-5292.

- ↑ Banerji, Debashish (2015). "Tagore Through Portraits: An Intersubjective Picture Gallery". In Banerji, Debashish. Rabindranath Tagore in the 21st Century. Sophia Studies in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Traditions and Cultures. Volume 7. Springer India. pp. 243–264. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2038-1_17. ISBN 978-81-322-2037-4.

- ↑ "Fakir Lalon Shai ... 120 years on". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ "Interview: Bengali Film Actor Priyangshu Chatterjee". Washington Bangla Radio USA. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ "Fakir Lalon Shai …123 years on". Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ "Lalon memorial festival begins in Kushtia today". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ L. Parshall, Philip (10 April 2007). Bridges to Islam A Christian Perspective on Folk Islam. InterVarsity Press. p. 89. ISBN 0830856153. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Muthukumaraswamy (Editor), M.D.; Kaushal, Molly (1 January 2004). Folklore, public sphere, and civil society. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. p. 161. ISBN 8190148141. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Mazhar, Farhad; Buckles, Daniel (1 January 2007). Food sovereignty and uncultivated biodiversity in South Asia essays on the poverty and the wealth of the social landscape. New Delhi: Academic Foundation in association with International Development Research Centre. p. 69. ISBN 8171886140. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Rahman, Syedur (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Bangladesh. Scarecrow Press. p. 179. ISBN 0810874539.

- ↑ Lalon; Āhamada, Oẏākila (Editor) (2002). Lālana gīti samagra. Ḍhākā: Baipatra. p. 12. ISBN 9789848116463. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Tofayell, Z. A. (1968). Lalon Shah and lyrics of the Padma. Dacca: Ziaunnahar. p. 144. OCLC 569538154. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "Feature Film". Banglapedia - the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh. Asiatic Society, Dhaka. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Acharya, Anindita (3 March 2015). "Prosenjit Chatterjee starts an Indo-Bangladesh production". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "Moner Manush receives Indian National Film Award". The Daily Star. 9 September 2011. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ Singh, Shalini (2 December 2010). "Moner Manush shines at IFFI". The Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ "Tanvir Mokammel films screened in Morocco". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2015-06-30.

- ↑ Raskin, Jonah (7 April 2004). American Scream Allen Ginsberg's Howl and the Making of the Beat Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 208. ISBN 0520939344. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

Further reading

- Muhammad Enamul Haq (1975), A History of Sufism in Bangla, Asiatic Society, Dhaka.

- Qureshi, Mahmud Shah (1977), Poems Mystiques Bengalis. Chants Bauls Unesco. Paris.

- Siddiqi, Ashraf (1977), Our Folklore Our Heritage, Dhaka.

- Karim, Anwarul (1980), The Bauls of Bangladesh. Lalon Academy, Kushtia.

- Capwell, Charles (1986), The Music of the Bauls of Bengal. Kent State University Press, USA 1986.

- Bandyopadhyay, Pranab (1989), Bauls of Bengal. Firma KLM Pvt, Ltd., calcutta.

- Mcdaniel, June (1989), The Madness of the Saints. Chicago.

- Sarkar, R. M. (1990), Bauls of Bengal. New Delhi.

- Brahma, Tripti (1990), Lalon : His Melodies. Calcutta.

- Gupta, Samir Das (2000), Songs of Lalon. Sahitya Prakash, Dhaka.

- Karim, Anwarul (2001), Rabindranath O Banglar Baul (in Bengali), Dhaka.

- Choudhury, Abul Ahsan (editor) (2008), Lalon Samagra, Pathak Samabesh.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tomb of Lalon. |

| Bengali Wikisource has original text related to this article: |