Lashmer Whistler

| Sir Lashmer Gordon Whistler | |

|---|---|

|

Lashmer Whistler, pictured here in the centre, with Home Guard commanders in Oswestry, 1954. | |

| Nickname(s) |

"Bolo" "Private Bolo" |

| Born | 3 September 1898 |

| Died | 4 July 1963 (aged 64) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1917–1957 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Royal Sussex Regiment |

| Commands held |

4th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment 132nd Infantry Brigade 131st Infantry Brigade 160th Infantry Brigade 3rd Infantry Division Northumbrian District and 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division West Africa Command Western Command |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire Distinguished Service Order & Two Bars Mentioned in dispatches (3) |

| Other work | Chairman, Committee on the New Army (1957) |

General Sir Lashmer Gordon Whistler GCB, KBE, DSO & Two Bars, DL (3 September 1898 – 4 July 1963), known as Bolo, was a senior officer of the British Army who served in both the First World War and the Second World War. During the latter, he achieved senior ranks serving with Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery in North Africa and North-western Europe. Montgomery considered that Whistler "was about the best infantry brigade commander I knew". In peacetime, his outstanding powers of leadership were shown in a series of roles in the decolonisation process, and he reached the rank of general.

Early life and career

Whistler was the son of Colonel A.E. Whistler of the British Indian Army and his wife Florence Annie Gordon Rivett-Carnac, daughter of Charles Forbes Rivett-Carnac. He was educated at St Cyprian's School where he was an outstanding sportsman, and on the recommendation of the headmaster was awarded a sporting scholarship at Harrow School. He played cricket for Harrow,[1] and was to remain a redoubtable batsman throughout his career.[2] He then went to Royal Military College, Sandhurst, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Royal Sussex Regiment in September 1917 and served on the Western Front during the Great War.[3] He was wounded twice, and on the second occasion he was taken as prisoner of war by the Germans before he had recovered. Later, he managed to escape from a prison train, but was re-captured within 20 yards of the Dutch border. He was then held at Ulrich Gasse in Cologne where he lost five stone and could hardly walk by the end of the war[4]

Inter-war years

In 1919, after the end of the Great War, Whistler remained in the army and was promoted lieutenant in March.[5] He also volunteered to join the Relief Force being sent to support the British Garrison at Archangel. He was posted to the 45th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers and saw some action on the River Dvina until its withdrawal when the White Russian army was defeated elsewhere.[6] It was his recounting of many anecdotes about the Bolsheviks that gave rise to his nickname "Bolo". He was posted to the 1st Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment on 24 October 1919. Serving with the British Army of the Rhine, he found his company quartered in the same Ulrich Gasse barracks where he had been a prisoner of war in the previous year. However, on the last day of the year he was sent to Ireland as one of the replacements for fourteen British officers who had been murdered the previous November. He remained in Ireland for four years and then went as Acting Adjutant to the Regimental Depot at Chichester. Shortly afterwards, he was sent to Hong Kong to protect British interests during civil war in China. He qualified as Italian interpreter in 1928. He was appointed Adjutant of the 5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment as a temporary captain on 1 May 1929,[7] this becoming a permanent rank on 30 September 1932.[8] In 1933 he was posted to Karachi and then to Egypt at the time of Mussolini's Italian invasion of Ethiopia.[9] It took Whistler twenty one years after being commissioned to achieve the rank of major[10][11] which he attained in August 1938. In 1938 he became Adjutant of the Royal Sussex Regiment and served in Palestine until the Second World War. He had not qualified for Staff College, and confided in his old Harrow and Sandhurst friend Reginald Dorman-Smith that he would end his military career in command of a battalion at most.[12] With little prospect of advancement to higher command, Whistler had been seriously considering leaving the army for civilian life when the Second World War broke out.[10]

Second World War

Battle of France, Dunkirk, and Home

When the Second World War broke out, Whistler was commanding the regimental depot at Chichester. On 5 February 1940 he became an acting lieutenant colonel and was appointed Commanding Officer of the 4th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, a Territorial Army unit. The battalion was on stand-by to go to Finland, but this did not happen. Whistler worked hard to transform the Territorial battalion into fighting shape and on 8 April they embarked at Southampton for Cherbourg where it became part of 44th (Home Counties) Infantry Division's 133rd Infantry Brigade. They moved to the Belgian border and to Courtrai. Under constant bombardment, Whistler had sent a famous message to Brigade Headquarters "Please may I have half a Hurricane for half an hour".[13] As the German Army advanced during the Battle of France, 4th Royal Sussex took up a defensive position at Caestre. An officer reported finding Whistler "standing in the middle of the street with a positive hail of explosives coming down all around". While his subordinates crouched by the side of the road, he "stood there with his hands in his pockets, laughing at us".[14] Although attacked by tanks planes and heavy artillery, the stand at Caestre was so strong that the Germans decided to by-pass this pocket of resistance.[15] Whistler was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his leadership of the battalion in France.[16][17] Orders were issued to withdraw to Dunkirk and the 4th Royal Sussex evacuated from there on 30 May. Whistler became known as "The Man who went Back to Dunkirk". Although secrecy surrounds this operation, Whistler's Adjutant was convinced he returned to look for any missing men, and the records show that he came back separately to the United Kingdom with a battalion of the Manchester Regiment on 1 June.[18]

For the next two years, the 44th Division served as part of XII Corps, defending south-east England. For part of this time the division was commanded by Major-General Brian G. Horrocks and the corps by Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery, both of whom recognised Whistler's leadership potential.[19] When Montgomery inspected Whistler's battalion, he "quickly realised that he was well above the ordinary run of battalion commanders" and "decided not to lose sight of him".[20] After the war Montgomery was to record that he had thought Whistler was the best infantry brigade commander in the army and that he had done well at divisional level as well.[21]

North Africa

In August 1942, Whistler arrived with the 44th Division in Egypt to join Montgomery's British Eighth Army, part of Horrock's XIII Corps. His 4th Royal Sussex was assigned to the Alam el Halfa Ridge for the Battle of Alam el Halfa, although most of the action took place below. Brigadier Lee, the commander of 133rd Infantry Brigade in the 44th Division fell ill and Whistler was appointed acting brigadier to replace him. He was subsequently transferred to command of 132nd Infantry Brigade,[22] which he led during the Battle of El Alamein[19] where it took over ground captured on 25 October and where he and his brigade major were slightly wounded.

As the advance moved forward to Benghazi, Whistler was transferred to command the 131st Lorried Infantry Brigade on 19 December 1942. This brigade had originally arrived in Egypt as part of the 44th Division but by this time was the mobile infantry element of the 7th Armoured Division. He led the brigade, which because of its role with armour was often in the forefront of events, through the rest of the fighting in North Africa until the surrender of the Axis forces in Tunisia in May 1943. Whistler led his troops through the Battle of El Agheila in December 1942, the capture of Tripoli in January 1943, and along the coastal strip capturing Msallata, Zuwara, Zaltan and Pisida. The brigade then took part in the Battle of Medenine on 6 March 1943 and the Battle of the Mareth Line at the end of March.[23] Whistler's frequent visits to the front line earned him the nickname "Private Bolo".[24] In the later stages of the Tunisia Campaign, the 7th Armoured Division was transferred to the British First Army, joining IX Corps, which by that time was commanded by Horrocks.[19] Whistler was awarded the first Bar to his DSO in April 1943 for "gallant and distinguished services in the Middle East",[25] and by 12 May 1943 German resistance in Tunis had ended and the North African Campaign finished.

Italian Campaign

For two months in the summer of 1943, the 7th Armoured Division remained at Homs for rest and training while the Allied invasion of Sicily took place. Whistler then took the 131st Brigade to join British X Corps under Lieutenant-General Richard L. McCreery in the Salerno landings on 9 September 1943. For the next stage in the Italian Campaign, he had 5th Royal Tank Regiment under his command as well as 131st Brigade in the break through to Vietri sul Mare. They crossed the River Volturno on 12 October in a tough fight under cover of darkness. There Whistler, by this time "very scruffy" and looking like a skeleton, met General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean, but shortly after had to spend a few days in hospital with a fever. Whistler's troops then broke through at Monte Massico through the gap between the Garigliano and Sessa Aurunca and met up with the British 46th Infantry Division.[26] In November 1943, the 7th Armoured Division received the news that it was to be transferred to the "Imperial Strategic Reserve" and would return to the United Kingdom.[27] For his services in Italy Whistler was awarded a second Bar to his DSO.[28] Whistler maintained a diary to which he committed his private thoughts, often questioning his own courage and abilities. On the way back to England he wrote "getting near England, Home, Beauty and the Brats. I don't think I have made any good resolutions but hope to keep fifteen minutes ahead of my job for the rest of the war. I would like to be able to do something towards peace afterwards, but am too simple a soldier probably to be of any use... A bit nervous of the great offensive but do not wish to miss it – wish I could go on with this outfit but have been too long with it. Am not fit for an Armoured Div and do not want a Bum Inf Div. What a life".[29]

Normandy and North West Europe

In January 1944 Whistler was transferred to command the 160th Infantry Brigade, part of the 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division, ahead of the Normandy Campaign. The 53rd Division was a 1st Line Territorial Army formation which had been based in Northern Ireland and England throughout the war and Montgomery's policy was to give a few experienced commanders to inexperienced brigades.[30] The 53rd Division was due to land in Normandy on 28 June 1944, but a week after D-Day (6 June 1944) the commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, Major-General Tom Rennie, was wounded and Montgomery called for Whistler and gave him command of the division as an acting major-general.[31][nb 1]

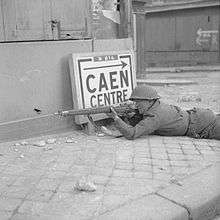

Whistler commanded the division throughout the campaign in north-west Europe. The 3rd Division captured Caen on 6 July during Operation Charnwood and then took part in Operation Goodwood. The division was extracted from the stalemate and assigned to Caumont-sur-Orne in Operation Bluecoat in the drive past Vire and captured Flers on 18 August. On 3 September, the 3rd Division began a move forward which was to take it 150 miles with its major action at the crossing of the Meuse-Escaut canal on 18 September. The division participated in Operation Market Garden and then in the Battle of Overloon, taking over from the U.S. 7th Armoured Division, to capture Overloon and Venray on 18 October after suffering heavy casualties. One of Whistler's subordinates observed the effect Whistler had on his troops: "I saw an infantry battalion on its way into battle. They were resting on both sides of the road when Bolo came back from the sharp end. He was driving himself, flag flying and his hat, as usual, on the back of his head. Every man stood up and waved to him as he went past, laughing and waving in reply".[34] For the following three and a half months, the 3rd Division was committed to hold the line along the Maas River. Whistler returned from leave to find his division on the move under Operation Veritable. They reached the Rhine on 12 March. Whistler's headquarters were in Schloss Moyland, where he was visited by Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, wearing the uniform of Honorary Colonel of the 5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment in tribute to Whistler. From 27 to 30 March, the 3rd Division crossed the Rhine and headed towards the River Elbe, crossing the Dortmund-Ems Canal at Lingen against stiff resistance. On 7 April, the 3rd Division was transferred to XII Corps and headed east with them to Bremen. From 13 to 20 April, the 3rd Division saw heavy fighting outside the town and on 26 April captured the ruins of the town. With the German surrender pending, Whistler was sent to Osnabrück to take over administration of a large area of Germany of Minden and Munster. He had to look after some 260,000 displaced persons and restore some order. In August, Whistler and the 3rd Division returned to England.[35]

Whistler was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath in March 1945,[36] and Mentioned in dispatches in August 1945 and April 1946 for his services during the campaign.[37][38][39] In June 1945, he was promoted to colonel (war-substantive) with the temporary rank of major-general.[40]

After the Second World War

Imperial Strategic Reserve

As he had not attended Staff College, Whistler was not qualified for high positions in the War Office. However, his outstanding success as a leader of troops during the war led him to a succession of increasingly senior command positions after the war,[19] particularly in the challenging environment of decolonisation. The 3rd Infantry Division became the Imperial Strategic Reserve, on five days notice to fly to any part of the world. Whistler took the Division to Egypt in November 1945 and was sent almost immediately to northern Palestine to police troubles between Israelis and Arabs.[19] In December he became General Officer Commanding British Troops in Egypt and shortly after ceased to be a member of 3rd Division. His major general rank was made substantive in February 1947, with seniority backdated to April 1946.[41]

Decolonisation

In January 1947 Montgomery selected Whistler to become General Officer Commanding British Troops in India. There was considerable communal violence prior to the grant of independence that required careful policing, but Whistler's main concern was the extraction of British units stationed in India. After final meetings with Lord Mountbatten and Jawaharlal Nehru, and a parade at the Gateway of India, Whistler left Bombay with the last British battalion on 28 February 1948.[42]

Whistler's next appointment on 1 June 1948 was Commander-in-Chief in the Sudan, which also gave him the title of Kaid Sudan Defence Force. He was also amused to find himself on the governing body of the country (the Governor General's Council), and also Minister of Defence answerable to the Legislative Assembly. He worked on Sudanising the Defence Force and within a year felt he had achieved what he had set out to do.[43] In January 1950 he was appointed District Officer Commanding, Northumbrian District and General Officer Commanding 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division TA to take effect in June 1950, and he left Sudan on 9 May.[44] His period of command was very short as on 5 January 1951 he was told he was to be appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, West Africa Command, to take effect on 10 May 1951.[45] He was also promoted lieutenant general from that date.[46]

Whistler's headquarters were at Accra, where he commanded the troops in Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Gold Coast and Gambia. As these countries were heading towards independence, Whistler's main concern was the Africanisation of the armed forces.[47] He was knighted as a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the New Year Honours in 1952. Sir John Macpherson, Governor-General of Nigeria, warned Whistler of the resistance to his speed of change, receiving the reply "Well I'm old enough and ugly enough to look after them. And I want to get rid of British NCOs at once and hurry up with the commissioned officers."[48] Young African soldiers were sent to Sandhurst and other colleges and Macpherson noted that one of his second lieutenants was John Ironsi. In September 1953 Whistler was offered Western Command in England from December 1953.

Western Command

On 1 December 1953, Whistler became the Colonel of the Royal Sussex Regiment[49] (a ceremonial title) and also became General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, Western Command.[50] His main interests were to build rapport with the civil authorities, bolster the Territorial Army and encourage recruitment and training of officers in Wales and its bordering west Midland and the north-west counties of England. In 1954 he was ear-marked as Army Commander designate in the event of an East-West war in continental Europe and in this role he played a leading part in the training exercise "Battle-Royal".[51] He was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath in the New Years Honours of 1955,[52] and was promoted to full general in July of that year.[53] He held the post of GOC Western Command until his retirement in February 1957,[54] following his promotion to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath the previous month.[55] Lord Mancroft recalled visiting Whistler at Chester and being amazed at his intricate knowledge of the Roman camp layout. He recalled a dinner later "Bolo got a fishbone stuck in his throat during dinner and went outside to clear the matter up. Nobody had told him that the regimental goat had been temporarily parked in the gentlemen's cloakroom pending its later ceremonial arrival, and Bolo returned quite shaken and very angry, having had the best of three rounds with the goat, and, I think, lost them all. As he said in his speech, nobody wants to fight a goat in a mess dress and spurs, even when you haven't got a fishbone stuck in your throat."[56]

Retirement

In April 1957, just before Whistler's retirement, Field Marshal Sir Gerald Templer asked him to become Chairman of the Committee on the Reorganisation of British Infantry.[57] Other members of the Committee included Lieutenant General Sir James Cassels. When this work was completed, Templar sent for him in January 1958 to chair another committee "to investigate and report on all aspects of discipline, training and economy in units". Whistler introduced his report with a Latin quotation attributed to Horace but in fact of his own composition.[58]

Whistler was appointed Deputy Lieutenant for the County of Sussex in 1957.[59]

In 1958 Whistler was appointed Colonel Commandant of the Royal West African Frontier Force,[60] being the last British officer to hold the post as it ceased to exist on 1 August 1960. In 1959, the governments of Nigeria and Sierra Leone also invited him to become Honorary Colonel of the Royal Nigerian Military Forces, and the Royal Sierra Leone Military Forces. Whistler was on very friendly terms with Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who sought his advice and judgement. Whistler was very concerned about the future of the Nigerian Army because it was split with the officers coming from the south of the country and the soldiers from the north.[61]

Whistler's interest and ability in shooting led him to take an interest in small-bore rifle shooting. He became Vice-President of the National Smallbore Rifle Association in 1958 and chairman in 1959.[62] He was also vice president of the National Rifle Association as well as the Sussex S.B.R.A. and he also managed the N.R.A. overseas teams. He led the British team which competed in the World Championships in Moscow, winning titles in the small-bore prone 40 shots.[63] He took great interest in the Chichester Rifle Club, opening its new range in 1961 and presented it with some of his medals. The Whistler Inter club trophy in his memory is still shot annually on the first Friday of April.

Whistler was elected to the Council of the Army Cadet Force Association on 21 October 1959 as the representative of the NSRA. He was elected Chairman of the ACFA on 18 October 1961.[64]

Whistler's last battle was against lung cancer, an illness which he concealed until November 1962. He died eight months later, aged 64, at the Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot.[65]

Personal life

Sir John Smyth V.C. wrote Whistler's biography "as a study in leadership" and noted four traits in his character: his humility, his humanity, his sense of humour and his devotion to his family. He summarised his breadth of character: "Bolo Whistler was a very human man; he drank and he smoked and he loved a party and he often used very strong language. But at the same time he was a man of very high ideals and Christian principles. In these matters he set a wonderful example. Often before a battle he would ask his padres to hold a short service, perhaps in a cornfield or any other convenient place."[66]

Whistler married Esmé Keighley, the sister of a naval officer who died as the result of the Russian campaign. The wedding took place at Eastbourne in 1926, and the reception was held at his old school St Cyprians, one of the ushers being then naval cadet Rupert Lonsdale.[67] Whistler and his wife had two daughters.

The Duke of Norfolk who was Whistler's subordinate in the Royal Sussex Regiment, and later his superior as Lord Lieutenant of Sussex said of him: "He was possibly the greatest man I ever knew".[68]

Kwame Nkrumah wrote "General Whistler was not only a great soldier, but a great man; he was to me a most sincere friend, frank and understanding, jovial and abounding in energy".[69]

"He had of course the presence and the personality which enabled him to win the hearts and minds of all who served under him. A decisive manner, often brutally frank and outspoken, he always had a twinkle in his eye and a most infectious grin. After every action he would always go and visit his field ambulance to see and offer a word of comfort and cheer to the wounded. A great Christian and a great soldier". Chapter Nine, Stalemate, page 58, Monty's Iron Sides From the Normandy Beaches to Bremen with the 3rd Division, Patrick Delaforce.

Publications

- Small Bore Rifle Shooting

Footnotes and citations

- footnotes

- citations

- ↑ Smyth (1967), p.35

- ↑ The Times Gen. Sir Lashmer Whistler- G. D. M. (G. D. Martineau) writes - Wednesday 17 July 1963

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 30280. p. 9438. 11 September 1917.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 40–41

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 31347. p. 6230. 1919-05-16. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 42–47

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33490. p. 2852. 1929-04-29. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33938. p. 3099. 1933-05-09. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 49–59

- 1 2 Mead (2007), p. 481

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 34538. p. 5024. 1938-08-05. Retrieved 2008-08-13.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp. 64–64

- ↑ Smyth (1976) p.71

- ↑ Peter Hadley, quoted in Smyth (1967) p.76

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 64–74

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 34893. p. 4261. 1940-07-09. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Mead (2007), pp. 481–482

- ↑ Smyth (1967), p. 80

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mead (2007), p. 482

- ↑ Bernard Montgomery Foreword to Smyth (1967) p.15

- ↑ Mead (2007), p. 484

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 88–91

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 91–96

- ↑ Smyth (1967), p. 18

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 35987. p. 1845. 1943-04-20. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 98–100

- ↑ Mead (2007), pp. 482–483

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36327. p. 255. 1944-01-11. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 101

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 101–106

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36829. p. 5619. 1944-12-05. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36897. p. 451. 1945-01-16. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37635. p. 3361. 1946-06-28. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 126

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 107–163

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37004. p. 1703. 1945-03-27. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36994. p. 1557. 1945-03-20. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37213. p. 4053. 1945-08-07. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37521. p. 1672. 1946-04-02. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37189. p. 3815. 20 July 1945.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 37880. p. 750. 1947-02-11. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp. 170–184

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp. 185–195

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 38962. p. 3502. 1950-07-07. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 39238. p. 2929. 1951-05-25. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 39224. p. 2639. 1951-05-08. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp. 196–202

- ↑ Sir John Macpherson interview in Smyth (1967) pp. 198–200

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40030. p. 6516. 1953-11-27. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40067. p. 207. 1954-01-05. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp.203–211

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40970. p. 215. 1957-01-04. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40596. p. 5483. 1955-09-27. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40992. p. 799. 1957-02-01. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 40960. p. 3. 1956-12-28. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp.210

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 41318. p. 1187. 1958-02-18. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp216-224

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 41246. p. 7115. 1957-12-06. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 41348. p. 2083. 1958-03-28. Retrieved 2008-08-11.

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp.226–233

- ↑ National Smallbore Rifle Association

- ↑ Smyth (1967) p 235

- ↑ Smyth (1967) pp239-242

- ↑ Times Obituary 1963

- ↑ Smyth (1967), pp. 22–24

- ↑ St Cyprian's Chronicle 1926

- ↑ Smyth (1967), p. 66

- ↑ Smyth (1967), p. 230

References

- Houterman, Hans; Koppes, Jeroen. "British Army Officers: Whistler, Lashmer Gordon". World War II unit histories and officers website. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- Mead, Richard (2007). Churchill's Lions: A biographical guide to the key British generals of World War II. Stroud (UK): Spellmount. pp. 544 pages. ISBN 978-1-86227-431-0.

- Smyth, Sir John (1967). Bolo Whistler: the life of General Sir Lashmer Whistler: a study in leadership. London: Muller. OCLC 59031387.

- The Times Obituary – Gen. Sir Lashmer Whistler Saturday 6 July 1963

External links

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Rennie |

General Officer Commanding 3rd Infantry Division 1944–1947 |

Succeeded by Hugh Stockwell |

| Preceded by Sir Cameron Nicholson |

GOC West Africa Command 1951–1953 |

Succeeded by Sir Otway Herbert |

| Preceded by Sir Charles Loewen |

GOC-in-C Western Command 1953–1957 |

Succeeded by Sir Otway Herbert |

_with_local_Home_Guard_commanders_at_Oswestry_(5470501779).jpg)