Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company

_-_cut%2C_Mauch_Chunk%2C_from_Robert_N._Dennis_collection_of_stereoscopic_views.jpg)

.jpg)

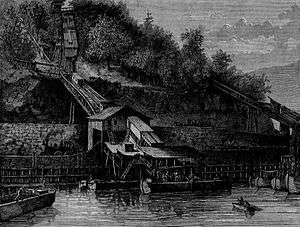

This painting shows the view[lower-alpha 3] from the (eventual) East Mauch Chunk near the foot of the Lehigh Gorge, across the mile-plus-long 'slack water pool' to the loading docks below Mount Pisgah. Its primitive company town, Mauch Chunk, now Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, sits in the shelf-land and gap under Mount Pisgah.

The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company was an extremely impactful and important mining and transportation company in Pennsylvania that operated from 1818 (1820 & 1822) through 1964. It had two predecessors both incorporated and which began operations in mid-1818.[1] It is widely cited in academia as a first case example of vertical integration in manufacturing in the U.S.,[4] combining source industries, transport, and goods output. In its first 50 years under the management of founders Erskine Hazard and Josiah White, the company spearheaded the Industrial Revolution in the United States greatly accelerating regional industrial development by taking on civil engineering challenges thought impossible and creating important transport and mining infrastructure.[4] The founders, having gotten into the coal industry as customers seeking a steady supply of fuel for their foundrys and mills on the falls of the Schuylkill River

Most Importantly for the United States industrial growth, the LC&N first established the Lower Lehigh Canal (begun 1818, usable 1820, improved 1821-24, and two-way 1827-29) and taught America how Anthracite could be burned to alleviate the ongoing first energy crises which was only getting worse. The Lehigh Canal would (using a 'bridging' river trip along the broad, generally placid Delaware River) inspire and connect with no less than four other canals by the early-1830s[lower-alpha 4]

Historic Synergies

Having tamed rivers and introduced mining technologies LCC & LNC's successes taken along with White's already tall reputation[4] created a newspaper and tavern buzz by 1821 that not only jump started America's brief Canal age[lower-alpha 5] and were the talk of business circles in the early 1820s, but also inspired and spurred others to invest in other raw materials industries and bulk transportation infrastructure projects;[lower-alpha 6] Further, the dawdling funding efforts behind the Schuylkill Canal project (begun in 1814) was finally funded and finished once the LNC had showed the way.[4] White and Hazard had backed the Schuylkill project since their mills were on the River, but became disgusted with the timid investment and management attitudes of its board, so explored the LCMC property and conducted feasibility examinations the winter of 1814-1815, so petitioned to build the canal that next year.[5]

Upon their return they inked what was effectively a no cost option to take over management of the LCMC mines and mining rights; guaranteeing one ear of corn per year as a rental for the next 20 years.[6][7] built the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad and had its hands in many other northeastern Pennsylvania shortline railroads, spurs, and subsidiaries; created the Ashley Planes and made or supported means to other novel solutions of transport problems;[lower-alpha 7] and created transport corridors still important today.[lower-alpha 8]It also pioneered the mining of anthracite coal in the United States, acquiring virtually the entire eastern lobe of the Southern Pennsylvania Coal Region,[8] and brought in Welsh experts to bootstrap Iron production using blast furnace technology in the Lehigh Valley, building the first six such furnaces and puddling furnaces to create steel,[4] which the company then provided to its own wire rope (steel cable) manufactury, the countries first it set up in Mauch Chunk.[4][5] Completing the vertical integration, the wire ropes were then marketed to other mining operations, cable railways, and other industries needing high tensile reliability in managing weighty loads.[4]

Buying out partner George Hauto, and forming the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (LC&N) in 1822 by combining the Lehigh Coal Mining Company (1893), the Lehigh Coal Company (then, leasing the lCMC's properties) and the Lehigh Navigation Company, it represented the first merger of interlocking companies in the United States.[4] Five years later,[lower-alpha 9] the company built the Mauch Chunk and Summit Hill Railroad, the first coal railroad and just the second railroad company in the country to be constructed after the Granite Railroad of Quincy, Massachusetts.[lower-alpha 10] It was founded by industrialists Josiah White (1780-1850) and Erskine Hazard (1790-1865),[9] who sought to improve delivery of coal to markets.[10] and a thickly accented German immigrant miner named Hauto.[7]

The company is known in the Lehigh Valley as the "Old Company", as distinct from the later 1988–2010 company: the nearly same named Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company— the 'New Company', to the people of the region.[11]

Development

• Jim Thorpe/Mauch Chunk is just off the right edge of this map, which shows the rough terrain, severe elevation changes and 9 miles (14.5 km) distance between Lehigh Coal Mining Company's mines at the divide and the county line. All the coal lands in the 14 miles (23 km) from Jim Thorpe to Tamaqua were owned by LC&N, over 8,000 acres (32 km2). Lehighton and Packerton are just downriver from Jim Thorpe, in the Mahoning Hills area.

• The Panther Creek stream running west below Lansford, Coaldale and summit hill is running downhill to the Little Schuylkill River watershed, at Tamaqua, over the terrain where the Old company built the Panther Creek Railroad from Tamaqua Junction to Lansford and the mines above Nesquehoning. LC&N later built the Hauto Tunnel, shortening the trip to points east some 12 miles, and avoiding delays from the crowded rail nexus at Delano Junction.

In 1792, hunter Philip Ginter discovered coal[13] on Sharpe Mountain—a peak on Pisgah Ridge near the border between Schuylkill and (today's) Carbon Counties. The Lehigh Coal Mine Company was founded the following year, but management proved weak and it was eventually absorbed by the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company.[14]

Lehigh Coal Mine Company

The Lehigh Coal Mine Company (LCMC) was founded in 1792[1] (incorporated 1793) with enough money to buy 10,000 acres[1] in and around the Panther Creek Valley and along Pisgah Ridge,[1] and the aim of hauling anthracite from the large deposits on Pisgah Mountain near what is now Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, to Philadelphia via mule train to arks built near Lausanne[lower-alpha 11] on the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers. The mining camps were over 9 miles from the Lehigh at Mauch Chunk. Sporadically active between the years of 1792 and 1814, the Lehigh Coal Mine Company was able to sell all of the coal it could get to fuel-hungry markets, but lost many a boatload on the rough waters of the unimproved Lehigh River, so actually just as often lost money as made profits.[15][notes 1]

Eventually, the owners sold some coal to Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, who operated a wire mill foundry at the Falls of the Schuylkill near Philadelphia. White and Hazard were delighted by the quality of the fuel, and subsequently bought the LCMC's final two barges to survive the trip down the Lehigh. Convinced they could much improve upon the reliability of its delivery, they began in 1815 to inquire after the rights to mine the LCMC's coal and hatched a plan to improve the navigation on the Lehigh as a key step.

Lehigh Coal Company

White and Hazard very shortly found themselves advised repeatedly that both the improvements, and the mining operation at Summit Hill, having each repeatedly failed miserably time after time, were both considered crackpot schemes, usually by differing groups of potential investors; the majority opinion being the improvements were more possible, and the coal mining was less likely to be a success. Accordingly, they secured other investors by forming two companies: The Lehigh Coal Company (LCC) and the Lehigh Navigation Company, and began seeking legislative approval for improving the Lehigh River with a navigation.

The desired opportunity "to ruin themselves," as one member of the Legislature put it, was granted by an act passed March 20, 1818. The various powers applied for, and granted, embraced the whole range of tried and untried methods for securing "a navigation downward once in three days for boats loaded with one hundred barrels, or ten tons." The State kept its weather eye open in this matter, however, for a small minority felt that these men would not ruin themselves. Accordingly, the act of grant reserved to the commonwealth the right to compel the adoption of a complete system of slack-water navigation from Easton to Stoddartsville if the service given by the company did not meet "the wants of the country."— Brenckman, History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania (1884)

In 1817, they leased the Lehigh Coal Mine company's properties and took over operations, incorporating on October 21, 1818, as the Lehigh Coal Company along with partner Hauto. They petitioned the legislature and propose acquiring rights to make improvements of the river, for which there was a string of supportive legislation going back decades.

In 1820, White and Hazard bought out Hauto and dissolved the LCC on April 21, 1820.[16]

Under the conditions of the lease, it was stipulated that, after a given time for preparation, they should deliver for their own benefit at least forty thousand bushels of coal annually in Philadelphia and the surrounding districts, and should pay, if demanded, one ear of corn as a yearly rental.— Brenckman, History of Carbon County, Pennsylvania (1884)[17]

The next hurdle surprised White and Hazard—there were in general, as was witnessed by the legislator's comments, a wide divergence of opinion as to whether the Lehigh could be tamed, and perhaps more surprising, there were less backers of any scheme to continue mining coal from the lands held by LCMC—there were simply too many failures over the 24 years of its operations for the peace of mind of many investors. Accordingly, three times the funds were raised to improve the river as were raised to put the mining U delivery of coal onto a regular paying basis.

Given permission, the two companies went to work, and overstocked the market demand in 1820, having opened practical, though not ideal navigability of the Lehigh over four years ahead of their targeted 1824. Coal mining and delivery by grading a near constant descent mule track from Summit Hill to feed a loading chute at the huge slack water pool created at Mauch Chunk, went well as well; the coal deposits were essentially outcrops needing little effort to extract.

Riding this success, the two companies were merged into the Lehigh Navigation Company, resolved to apply the high tech of the Canal Era (canals, locks, rails) to bringing coal to their foundries and the stoves and furnaces of Philadelphia and beyond.

Lehigh Navigation Company

Having displayed great technological skills by creating the world's first iron wire suspension bridge, which spanned the Schuylkill River at their wire works, White and Hazard schemed with other industrialists to secure a reliable source of anthracite.

To move the coal to market, they entered political negotiations to acquire rights to tame the turbulent and rapids-ridden Lehigh River for navigation. By 1817–18, they had organized the separate Lehigh Navigation Company and had written stock flyers announcing plans to deliver barge loads of coal regularly to Philadelphia by 1824.[lower-alpha 12] The LCMC had trouble delivering Anthracite to Philadelphia at costs cheaper than imported Bituminous Coal from Britain or Virginia. Their last expedition had been sent out in 1813 during the war & blockade caused bituminous shortages, and by the time five arks were sent down river, three sank, leaving the directors of LCMC disgusted and unwilling to fund more losses.[18]

The company began to prepare plans and surveyed sites, and when the state legislature approved the river work in 1818, immediately hired teams of men and began to install locks, dams, and weirs, including water management gates of their own novel design.[1]

The desired opportunity "to ruin themselves," as one member of the Legislature put it, was granted by an act passed March 20, 1818.[14]

A brief history of the navigations beginnings as Brenckman related in 1884:

The improvement of the Lehigh was begun at the mouth of the Nesquehoning creek, during the summer of the year 1818, under the personal supervision of Josiah White. The plan adopted was to contract the channel of the river in the form of a funnel, wherever it was found necessary to raise the water, throwing up the round river-stones into low walls or wing dams, thus providing a regular descending navigation.But it soon became apparent that the carrying out of this plan would not insure sufficient water in seasons of drought to float a loaded ark or boat, and the success of the whole enterprise hung in the balance. In this contingency, Josiah White, who was a man of great resourcefulness and mechanical ingenuity, resorted to the expedient of creating artificial freshets. Dams were constructed in the neighborhood of Mauch Chunk, in which were placed sluice-gates of peculiar design, invented for the purpose by White, and by means of which water could be retained until required for use. When the dam became full and the water had run over it long enough for the river below to regain its ordinary depth, the sluice-gates were let down, while the boats, which were lying in the pool above, passed down with the artificial flood. In this manner the difficulty was overcome. Crews were sent up Mount Pisgah to improve the mule trails down from the coal deposits at Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, and others to build docks, boat building facilities, and the canal systems head end pool and locks.

— Fred Brenckman, The History of Carbon County Pennsylvania

The canal head end needed a location where barges could be built and timber and coal could be brought into slack water. The challenge was to do it above the gap made by the east end of Mount Pisgah, a hard rock knob that towers 900 feet above the Lehigh River towns Jim Thorpe (formerly Mauch Chunk) to the towns west, and Nesquehoning to its north. Both towns are built into the flanks, the traverses, of the mountain, with flats along the river banks. (A few decades later, railroads would follow the canals.)

Within the next two years, White and Hazard constructed a descending navigation system that used their unique "bear trap" or hydrostatic locks, which allowed the passage of coal boats by means of artificial floods. The coal arrived at the head end from the mines at Summit Hill or down along the steep mule trail from near the headwaters of Panther Creek. It floated down the navigation; at journey's end, the barges were sold as fuel or for Delaware basin transports.

The navigation company began shipping significant quantities of coal by early 1819, ahead of expectations, and attained their goal of regular shipments in 1820.[19]

In 1820, the company was combined with the Lehigh Coal Company with the ouster of George Hanto, but was not rechartered officially until 1822.

Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company

By late 1820, four years ahead of their prospectus's targeted schedule, the unfinished but much improved Lehigh Valley watercourse began reliably transporting large amounts of coal to White's mills and Philadelphia. The nearly 370 tons of coal brought to market that year not only salved the winter's fuel shortage but created a temporary glut. After buying out co-founder George Hauto, White and Hazard reworked their lease deal with the Lehigh Coal Mine Company, and merged it with the Lehigh Coal Company, acquiring ownership of its 10,000 acres spanning three parallel valleys in the 14 miles (23 km) from Mauch Chunk to Tamaqua. A few months later, they merged the LCC and the Lehigh Navigation Company. In late 1821, they filed papers to incorporate Lehigh Coal & Lehigh Navigation, which took effect in 1822.

Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroad

In 1827, the Company in one massive well organized effort, completely built the 9.2 miles (14.8 km) of America's second railroad using the road bed of the wagon road built in 1818-19 in just a few months[1] — a gravity railroad named the Mauch Chunk and Summit Hill Railroad (or similar name variants) using wooden sleepers on a gravel substrate (as did most more modern railways) — to bring coal from mines to river more efficiently.[20] The work went quickly since the right-of-way surveyed by White (well before 1818's charter[lower-alpha 13]) ran along the virtually uniform gradient created by grading the original mule trail, work overseen by Hazard in 1818.

During the summer of 1827, a railroad was built from the mines at Summit Hill to Mauch Chunk. With one or two unimportant exceptions, this was the first railroad in the United States.[lower-alpha 14] It was nine miles in length, and occupied the route of the old wagon road most of the distance.Summit Hill, lying nearly a thousand feet higher than Mauch Chunk, the cars on the road made this descent by gravity, passing the coal, at their destination to the boats in the river by means of inclined planes and chutes. The whole of this plan was evolved by Josiah White, under whose direction it was consummated in a period of about four months. The rails were of rolled bar-iron, three-eighths of an inch in thickness and an inch and a half in width, laid upon wooden ties, which were kept in place by means of stone ballast.

The loaded cars or wagons, as they were then termed, each having a capacity of approximately one and a half tons, were connected in trains of from six to fourteen, being attended by men who regulated their speed.

Turn-outs were provided at intervals and the empty cars were drawn back to the mines by mules. They descended with the trains in specially constructed cars, affording a novel and rather ludicrous spectacle.[lower-alpha 15]

Thirty minutes was the average time consumed in making the descent, while the weary trip back to the mines required three hours.

— Brenckman, History of Carbon County (1894)

The wagon road to become gravity railroad ran from what later became Summit Hill along the south side of Pisgah Ridge to Mount Pisgah to the canal's loading chute over 200 feet (61 m) above the canal banks,[lower-alpha 16]

Mill Parks

Founders White and Hazard were at first, mill and foundry owners acting decisively to secure fuel for their main businesses prior to 1815's application for right-of-way legislation and optioning the sad-sack LCMC operations. In 1814, the partners had actually invested first in the rival Schuylkill Canal where they'd become disgusted with the planning, funding, and lack of commitment by other board members—their concerns take on added weight given the Schuylkill didn't operate until 1823 when LC&N had blazed the way. White's innovative Bear Trap lock-gate and system was based on creating an triggerable artificial flood, depending upon water flow to float the boats past the rapids obstructions. It is little wonder that as he surveyed the Lehigh, he also made note where a water powered mill could be harnessed, and the legislative act would effectively give the LNC ownership of the entire river. These rights were not released back to Pennsylvania until 1964.[lower-alpha 17]

So once 'emergency' improvements on the canal[lower-alpha 18] used its founder's knowledge and experience on the Little Schuylkill to develop the waterpower sites along its waterways into early industrial parks. By 1840, the Abbott Street area near Lock 47, now part of Easton's Hugh Moore Park, employed over 1,000 men in almost a dozen factories. This fostered the industries of Allentown, Bethlehem, and their products and the connection with the Delaware Canal (managed for the state by LC&N after 1834)<ref, the development of the Industrial Revolution of greater Philadelphia.

Blast Furnaces

In TBDL directors White and Hazard brought in Welsh technical experts to establish the Lehigh Valleys first Blast Furnaces.

Wire Rope Manufactury

In TBDL, probably as part of the Ashley Planes cable railroad work up and spurred by the developing need to mine down shafts as surface deposits were exhausted, Josiah White and the LC&N created the nations first Wire rope factory in Mauch Chunk.

Upper Lehigh Canal

With rights of eminent domain granted by the 1837 revisions to the Main Line of Public Works legislation, the 45 miles (72 km) Lower Lehigh Navigation was extended upriver another 39 miles (63 km) (the Upper Lehigh Canal) through the Lehigh Gorge from Jim Thorpe to White Haven and completed in 1843, giving it the largest carrying capacity of any U.S. canal.

Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad

With a unified legislative and executive push, LC&N spun off a subsidiary to build a railroad connection to the Susquehanna at Pittston just north of Wilkes-Barre over very rough terrain. The multi-modal project used a cable railroad called the Ashley Planes, and double-tracked connecting trackage from its foot at Ashley to the barge docks of Pittston and eventually linked up with the seven first-class railroads that drove spurs into the valley to haul anthracite. The Ashley Planes summit end connected to an assembly yard at Mountain Top, Pennsylvania, and sourced a steep double-tracked rail branch to White Haven where it had loading docks with a meeting of transport technologies feeding an new extension of its Lehigh Canal through the difficult terrain of the Lehigh Gorge. With the political push to connect Philadelphia and the Delaware to the Northern Coal Fields in the Wyoming Valley and to the Susquehanna River, LC&N formed the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad empowered with rights of eminent domain. Eventually, both the LC&N Company's Lehigh Navigation and the L&SRR were extended upriver through the Lehigh Gorge from Jim Thorpe to White Haven.

Other LC&N railroads

By the later 1820s through the mid-1830s, the civic and business leaders of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey were anxious to connect their young factories with the markets of the trans-Appalachian territories being settled by tens of thousands of westward migrants. To compete with the B&O Railroad and Erie Canal, they launched the Main Line of Public Works to benefit the manufacturers of the Delaware region.

The LC&N built a succession of small but influential shortline railways as joint ventures with other investors, each of which concurrently solved an earlier irrealizable and intractable civil construction project. Ownership and operations of all these, as well as their initial railway, the Mauch Chunk & Summit Hill Railway, were ultimately combined under the umbrella of their second, the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad (Today, this is a holding company that owns and leases the trackage rights to more visible operating road companies for many important rail corridors in northeast Pennsylvania.)

- Subsidiary shortlines

- Nesquehoning & Mahanoy Railroad: Having gained civil engineering experience running a freight line through most of the length of the Lehigh River and across the Delaware, the LC&N chafed at the transport bottleneck of the Panther Creek Valley. With the increasing power of locomotives, the company surveyed and pushed a seven-mile grade up through the winding slopes north of the Nesquehoning Ridge, with several descents, connecting near Hazelton, and the wider valleys of Mahanoy Creek, including that at Tamaqua, Pennsylvania, along the Little Schuylkill River near the outlet of Panther Creek. From Tamaqua, tracks also reached along the Schuylkill Valley to feed the industries of Reading, Pennsylvania, and surrounds.

- Panther Creek Railroad: Having reached Tamaqua, the company built the PCR to reach the main coal-bearing lands 5 to 6 miles to the east up the Panther Creek Valley.

- Hauto Tunnel: Shipping large heavy coal consists over the steep gradients of the Nesquehoning shortline was costly, so eventually the company cut a mile-long tunnel through Nesquehoning Ridge into downtown Lansford, Pennsylvania, which became for a time the seat of its corporate headquarters. This gave the company three means of bringing coal from its mines along Pisgah Ridge and Nesquehoning Mountain until it sold the Mauch Chunk Switchback Railway, which was operating mostly as a prime tourist attraction: the world's first roller coaster.

Lehigh and New England Railroad

The acquisition of the Lehigh and New England[21] allowed the LC&N to stop leasing rights to the CNJ and transfer them instead to the new acquisition.

Surviving 143 years

By the middle of the 20th century, coal demand softened, thanks to the replacement of steam locomotive with diesels and the growth of other forms of heating. Expenses for upkeep outstripped declining canal revenue, forcing the Lehigh Navigation to close in 1932. A large portion of the once-widely diversified LC&N depended upon coal, while subsidiaries owned the railroads and other profitable arms. Consequently, various boards oversaw gradual contraction of the company and sales of bits and pieces. In 1966, Greenwood Stripping Co. bought the remaining coal properties, most located as originally exploited along the Panther Creek Valley, and sold them eight years later to Bethlehem Mines Corp

Shareholders dissolved the company in 1986, after it sold its last business, Cella's Chocolate Covered Cherries, to Tootsie Roll.[21]

The new company

The company name remained associated with anthracite mining through the independently founded and otherwise unrelated Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company, incorporated in 1988. While unrelated legally, the 'New Company' as it's known in the area was spearheaded by a previous officer and stockholder: James J. Curran Jr. took over Lehigh Coal from Bethlehem Mines Corp. in 1989, and through the 1990s it remained the largest producer of U.S. anthracite, which is now a specialty product. In 2000, Lehigh Coal shut down and laid-off 163 employees, saying plunging coal prices made it impossible to make a profit. The company reopened in 2001 with help of a last-resort $9 million loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In 2010, in bankruptcy proceedings once again,[22] the company was purchased by one of its bigger creditors[22] at auction, BET Associates, who were affiliated with Toll Brothers.[22] The company properties in between Lansford and Nesquehoning, boasting an EPA permit sign in the same Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company name at the company gates along Rt-209 were observed in operation during mid-July 2013.

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Brenckman's History of Carbon County, the last LCMC operation, launched in the shortages worsened by the War of 1812, built five boats and filled them, spending over a year overall. Three of the five sank before reaching safe waters, and the two remnants were purchased by White and Hazard.

- ↑ The north end of the Solomon Gap cutting would also connect Mountain Top's rail yard to the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad's 'back track', which (with the new power of steadily improving steam locomotive drawing power) was built about 1855,[2] and descended at a steep gradient over 9 miles (14 km)[3] twisting and winding down the north and west faces of the ridges above the east-side Susquehanna River valley. Once the back track reached the broad floor of the Wyoming Valley at the wye outside Coxton yard, then back to the LC&N's rail yard at Ashley.

- ↑ Bodner's Painting of Mauch Chunk coal chute—The chute drops 200' from a shelf on Mount Pisgah, today called Upper Jim Thorpe (North Ave. area).

- ↑ The view from East Mauch Chunk near the foot of the Lehigh Gorge was likely from the trail where the LC&N backed Beaver Meadows Railroad would not much later construct its tracks from Beaver Meadows, Weatherly and Penn Haven (at the confluence of the upper Lehigh and the Black Creek to reach the Lehigh Canal.[4]

- ↑ enumerate four Lehigh Canal's canal connections: Delaware Canal, Delaware and Hudson, Morris Canal, and the Delaware and Raritan. Does not include the Chesapeake canal, but the docks in Philadelphia and coastal shipping accepted coal from LC&N for its first decade.[4][5]

- ↑ The Lehigh Canal was a landmark achievement, succeeding where a weary list of attempts to improve the Lehigh Rivers navigability had failed.[4] Delivering ever increasing tonnages of coal from 1818, and by providing the new High Tech fuel, Anthracite, the LCC and LNC's successes and failures (Severe ice damage to the canal in both 1821 and 1824, were quickly repaired restoring services and avoiding an energy shortfall before coal stocks were depleted.) and other news worthy events, such as Josiah White's petition to the state to allow a ship canal lock system be chartered on the Delaware in 1823,[4][5] kept the company very visible.

- ↑ The Delaware and Hudson Canal and railroads were directly inspired by LC&N's successes; the brothers pushing the project began searching for Anthracite in 1821, , months after Arks of coal had reached Philadelphia.

- ↑ Bringing affordable steel processes[4] and then making the first wire rope factory,[4][5] justify the conclusion.

- ↑ Virtually all main trackage (away from the Delaware River) except the Ashley Planes and Summit Hill and Mauch Chunk Railroads laid down by LC&N in a rail corridor (or its sometimes eventual subsidiaries), is still operated by the Reading, Blue Mountain and Northern, or the Norfolk-Southern Railways. In short, these roads were strategic paths. Two exceptions, the Lehigh and New England Railroad did suffer severe attrition and abandonment as did some of the trackage along the Lehigh once belonging to the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Lehigh and Susquehanna Railroad subsidiary company—CONRAIL kept some parallel trackage and tore up other redundant stretches.

- ↑ The Delaware and Hudson Canal project (New York charter) needed to charter land grant rights to construct the gravity railroad and inclined planes of the Pennsylvania subsidiary Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad, which they applied for in 1826 and news of that may have inspired White and Hazard to lay rails to improve throughput on their mule powered wagon road. Early operations without rails sent coal down once a day, needing over an hour to reach the bottom chute building dump track, and the round trip back took most of a day, even in summer.[4] After rails were laid, mules pulling the 5 long tons (5.1 t) hopper cars back up the 9 miles (14 km) trip only took four hours, so twice a day deliveries became the rule.[4]

- ↑ 1826 saw several important rail transport companies obtain incorporation, charters, or both, but only the first chartered in Pennsylvania, the Delaware & Hudson Railroad began construction before 1830 alongside the Baltimore & Ohio. By 1827 the SH&MCRR had carried passengers, and was charging passengers in 1829

- ↑ Lausanne Township, and Tavern/Inn was a small pre-1800s settlement near the mouth of Nesquehoning Creek and the upper Lehigh. 19th century historians often mention the place as it was also one terminus of the TB found turnpike connecting the Lehigh Valley through Beaver Meadows and the Susquehanna River valleys.

- ↑ The irregular stocks available from the mis-managed Lehigh Coal Mine Company had been one huge problem retarding acceptance of Anthracite as a fuel alternative.[18]

- ↑ Brenckman does not say when White surveyed the mule road, but his accounts make it clear that it was instantly ready for work crews to begin when the enabling legislation was signed in March 1818—work crews were assembled and departed Philadelphia within the week. The LCC formation took place several weeks after work crews were sent out to begin both the Navigation and the road construction projects.

- ↑ Brenckman is ignoring that at least three railroads that would become famous were formally chartered in 1826, including the first constructed, the 3 mile Granite Railroad in Quincy, Massachusetts. The SH&MC was not even the first chartered in Pennsylvania, that honor goes to the similar coal road, the Delaware and Hudson Gravity Railroad subsidiary of the Delaware and Hudson Canal inspired by the LC&N's success backed by other Philadelphia businessmen.

- ↑ Elsewhere, Brenckman details that special mule cars carrying the animal power component of the system were sent down after, or as the trail car of, the coal consists, providing at least part of the spectacle to which he refers. Throughput was kept up by sending 2-3 runs per day at first, then by round-the-clock operations by lantern headlights until demand outstripped the capability of keeping up. By then with the experience of engineering the Ashley Planes ascent railways, White devised the Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk's return cable railroad.

- ↑ The lower terminal railyard thus ended in what is today the housing in "Upper Mauch Chunk", ending at Mauch Chunk above the present-day North Avenue. During these same years, it also began converting its descending navigation system into a two-way system.

- ↑ Check 1964 date in The Delaware and Lehigh Canals

- ↑ Lower Canal completed initially in late 1820, there were several places experience in 1821 showed a need for re-engineering. In the Winter of 1821-8122, the system was severely damaged for the first time, taking the LCN's total cash reserves to repair. This situation resulted in directors White and Hazard seeking additional capital funds leading to the dissolution of the LCC and LNC and the incorporation of the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company.

References

Sources

- Fred Brenckman, Official Commonwealth Historian (1884). HISTORY OF CARBON COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA (2nd (1913) ed.). J. Nungesser, Harrisburg, PA (Archive.org e-reprint). p. 600., downloadable pdf version

- Archer B. Hulbert. "CHAPTER III. The Mastery Of The Rivers". In [EBook #3098]= Allen Johnson, Release Date: February 28, 2009, Last Updated: February 4, 2013. The Paths of Inland Commerce, A Chronicle of Trail, Road, and Waterway, Volume 21 in The Chronicles of America Series, June, 1919. Project Gutenberg (reprints).

- Clint Chamberlin. "LEHIGH AND SUSQUEHANNA DIVISION". North East Rails. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Alfred Mathews & Ausin N. Hungerford (1884). The History of the Counties of Lehigh & Carbon, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Ancestry.com, Transcribed from the original in April 2004 by Shirley Kuntz.

- Frank Whelan (1986-06-08). "Ex-executive Recalls Decline And Fall Of Lehigh Coal And Navigation Co.". The Morning Call, June 08, 1986.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brenckman. "PROGRESS OF SETTLEMENTS AND INTERNAL IMPROVEMENTS IN CARBON COUNTY". HISTORY OF CARBON COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA. Sub-title: "Beginning of Permanent Settlement - The Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company - The Canal - Railroad Building, etc.", J. Nungesser, Harrisburg, PA (Ancestry.com selective e-extract). pp. 595–597., 627 pages, Full alternative source: [historyofcarbonc00inbren.pdf-https://archive.org/details/historyofcarbonc00inbren] (pdf)

- ↑ TBDL - relocate this date and check

- ↑ GoogleEarth ruler tool, measured north side to Avoca at 1st junction.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Archer B. Hulbert, The Paths of Inland Commerce, A Chronicle of Trail, Road, and Waterway, Vol. 21, The Chronicles of America Series. Editor: Allen Johnson (1921)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bartholomew, Ann M.; Metz, Lance E.; Kneis, Michael (1989). DELAWARE and LEHIGH CANALS, 158 pages (First ed.). Oak Printing Company, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Center for Canal History and Technology, Hugh Moore Historical Park and Museum, Inc., Easton, Pennsylvania. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0930973097. LCCN 89-25150.

- ↑ "Soon after this failure, Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, who were engaged in the manufacture of wire at the Falls of Schuylkill, having obtained good results in their experiments with the coal they had purchased from Cist, Miner and Robinson, secured control of the entire property of the Lehigh Coal Mine Company under the terms of a lease for twenty years. George F. A. Hanto joined them in the venture, and was largely depended upon to secure the necessary financial assistance to make the property productive. Under the conditions of the lease, it was stipulated that, after a given time for preparation, they should deliver for their own benefit at least forty thousand bushels of coal annually in Philadelphia and the surrounding districts, and should pay, if demanded, one ear of corn as a yearly rental.", Brenckman, pp. 77-78

- 1 2 Hurlbert, Chapter III, quote: Believing that coal could be obtained more cheaply from Mauch Chunk than from the mines along the Schuylkill, White, Hauto, and Hazard formed a company, entered into negotiation with the owners of the Lehigh mines, and obtained the lease of their properties for a period of twenty years at an annual rental of one ear of corn.

- ↑ FRANK WHELAN (1986-06-08). "Ex-executive Recalls Decline And Fall Of Lehigh Coal And Navigation Co.". The Morning Call, June 08, 1986.

Lehigh Coal and Navigation controlled 8,000 acres of coal lands running from Jim Thorpe to Tamaqua, 14 miles away. This comprised the entire eastern end of the southern anthracite field.

- ↑ National Canal Museum – The Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company Accessed 2008-09-18.

- ↑ http://siris-archives.si.edu/ipac20/ipac.jsp?uri=full=3100001~!140147!0&term=#focus

- ↑ Per paid guide presentation in July 2013 at the Lansford-Coaldale 'Number Nine Museum' in the Panther Creek Valley.

- ↑ Sevon, W. D., compiler, 2000, "Physiographic provinces of Pennsylvania", Pennsylvania Geological Survey of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Pennsylvania Geological Survey, 4th ser., Map 13, scale 1:2,000,000.

- ↑ The Early Days of Summit Hill, updated September 24th, 2009, www.summithill.com, [email protected], (accessed: 9 September 2013)

- 1 2 Hurlbert, June, 1919, CHAPTER III. The Mastery Of The Rivers

- ↑ Brenckman's History of Carbon County, pp. 594: The task which Josiah White and Erskine Hazard undertook, that of making the Lehigh a navigable stream, was one which had before been several times attempted, and as often abandoned as too expensive and difficult to be successfully carried out. The Legislature was early aware of the importance of the navigation of this stream, and in 1771 passed a law for its improvement. Subsequent laws for the same object were enacted in 1791, 1794, 1798, 1810, 1814, and 1816, and a company had been formed under one of them which expended upwards of thirty thousand dollars in clearing out channels, one of which they attempted to make through the ledges of slate about seven miles above Allentown, though they soon relinquished the work.

- ↑ Ancestry.com, p593: "We will remark here that the Lehigh Coal Company was incorporated by act of Oct. 21, 1818; that its leading characters were the same as those of the Navigation, White, Hazard, and Hauto; that the last named was bought out by his partners in March, 1820, and that on April 21, 1820, the two companies were consolidated under the title of the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company."

- ↑ Brenckman, p77

- 1 2

- ↑ Fred Brenckman (1884). HISTORY OF CARBON COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA. J. Nungesser, Harrisburg, PA (1913 Edition, selective extract e-reprint by Ancestry.com or Archive.org full e-reprint). pp. 595–597.

Early Lehigh Canal shipping tonnages summarized from text:

• 1820 -- 365 short tons (331 t), 1821 -- 1,073 short tons (973 t), 1822 -- 2,240 short tons (2,030 t),...

• 1825 -- 28,393 short tons (25,758 t), & 1831 -- 40,966 short tons (37,164 t); and further, Brenckman discusses that long before 1831 LC&N managers were both having and projecting further inability of timbering fast enough to build enough one way coal 'Arks' to keep up with demand increases. ... In the last year forty thousand nine hundred and sixty-six tons of coal were sent down, which required the building of so many boats that had they all been put together, end to end, they would have extended more than thirteen miles (13 miles (21 km)). - ↑ Poor, Henry Varnum (1860). HISTORY OF THE RAILROADS and CANALS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Sub-title: Exhibiting their Progress, Costs, Revenues, Expenditures & Present Condition. (Vol 1 of 3) John H. Shultz & Co., 9 Spruce St., New York City, 1860 (digitally republished as GooglePlay ebook accessed August 2016).

...The railroad first constructed in the State, and the second in the United States, was the Mauch Chunk and Summit Hill, from a place of the same name on the Lehigh Canal to the coal mines of the Lehigh Company. It was brought into use in 1827. It was originally laid with a flat bar, ... (digital reprint garbles figure. Brenckman lists a 'rolled' 1-1/2 inch flat iron bar, 3/8ths inches thick.)

- 1 2 http://articles.mcall.com/1986-06-08/news/2521866_1_parton-coal-industry-lehigh-coal

- 1 2 3 LC&N sold at auction

External links

- Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company Records in Beyond Steel: An Archive of Lehigh Valley Industry and Culture.

- Early Mining Pictures – Anthracite Mining pictorial: Mines & Structures operated by the L.C.& N., Summit Hill, Lansford and Coaldale, Pennsylvania.

- Switch-Back Gravity Railroad: Proprietary photos touring the LC&N built Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk Railroad, the 2nd railway in North America